Benin Malaria Operational Plan FY 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Critical Versus Robust Processing Unit Operations

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2021, 56, 1311–1321 1311 Original article Identification of critical versus robust processing unit operations determining the physical and biochemical properties of cassava- based semolina (gari) Andres´ Escobar,1,2* Eric Rondet,2 Layal Dahdouh,2,3 Julien Ricci,2,3 Noel¨ Akissoe,´ 4 Dominique Dufour,2,3 Thierry Tran,1,2,3 Bernard Cuq5 & Michele` Delalonde2 1 The Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), CGIAR Research Program on Roots Tubers and Bananas (RTB), Apartado Aereo´ 6713, Cali, Colombia 2 Qualisud, University of Montpellier, CIRAD, SupAgro, University of Avignon, University of La Reunion,´ 73 rue JF Breton, Montpellier 34398, France 3 CIRAD, UMR Qualisud, F-34398, Montpellier, France 4 Faculty of Agronomical Sciences, University of Abomey Calavi, Cotonou, Benin 5 UMR IATE, CIRAD, INRA, University of Montpellier, Montpellier SupAgro, Montpellier, France (Received 3 August 2020; Accepted in revised form 13 October 2020) Summary The gari-making process involves several unit operations (U.O.), some of which strongly influence the quality of the end product. Two contrasting process scales (laboratory-scale vs conventional) were com- pared in order to identify which U.O. were affected by the change of scale. U.O. that changed end-pro- duct characteristics depending on process scale were deemed critical; whereas U.O. that resulted in similar characteristics were deemed robust. The classification depended on quality attributes considered: rasping and roasting were critical for physical properties, in particular particle size which ranged from 0.44 to 0.89 mm between the two process scales; and robust for biochemical properties. -

GIEWS Country Brief Benin

GIEWS Country Brief Benin Reference Date: 23-April-2020 FOOD SECURITY SNAPSHOT Planting of 2020 main season maize ongoing in south under normal moisture conditions Above-average 2019 cereal crop harvested Prices of coarse grains overall stable in March Pockets of food insecurity persist Start of 2020 cropping season in south follows timely onset of rains Following the timely onset of seasonal rains in the south, planting of yams was completed in March, while planting of the main season maize crop is ongoing and will be completed by the end of April. The harvest of yams is expected to start in July, while harvesting operations of maize will start in August. Planting of rice crops, to be harvested from August, is underway. The cumulative rainfall amounts since early March have been average to above average in most planted areas and supported the development of yams and maize crops, which are at sprouting, seedling and tillering stages. Weeding activities are normally taking place in most cropped areas. In the north, seasonal dry weather conditions are still prevailing and planting operations for millet and sorghum, to be harvested from October, are expected to begin in May-June with the onset of the rains. In April, despite the ongoing pastoral lean season, forage availability was overall satisfactory in the main grazing areas of the country. The seasonal movement of domestic livestock, returning from the south to the north, started in early March following the normal onset of the rains in the south. The animal health situation is generally good and stable, with just some localized outbreaks of seasonal diseases, including Trypanosomiasis and Contagious Bovine Peripneumonia. -

The Gold Standard Micro-Programme Activity Design Document Template (Vpa-Dd)

TITLE OF THE MICRO-PROGRAMME: GS2489 Efficient cookstoves in Benin and Togo ANNEX AO – THE GOLD STANDARD MICRO-PROGRAMME ACTIVITY DESIGN DOCUMENT TEMPLATE (VPA-DD) CONTENTS A. General description of micro-programme activity (VPA) B. Eligibility of VPA and Estimation of Emission Reductions C. Stakeholder comments Annexes Annex 1: Contact information on entity/individual responsible for the VPA Annex 2: Information regarding public funding This template shall not be altered. It shall be completed without modifying/adding headings or logo, format or font. 1 TITLE OF THE MICRO-PROGRAMME: GS2489 Efficient cookstoves in Benin and Togo SECTION A. General description of micro-programme activity (VPA) A.1. Title of the micro-scale VPA: Title: GS2489 Efficient cookstoves in Benin and Togo – VPA2 – EcoBenin – Wanrou efficient cookstoves in Atacora/Donga region GS nr: GS6008 Date: 28/08/2017 Version: 01 A.2. Description of the micro-scale VPA: >> The departments of Atacora / Donga, are suffering from severe deforestation due to the rapid increase of its population and their energy needs. 91% of the households in the Atacora/Donga departments use fuelwood as main combustion fuel.1 According to the document SCRP -Benin 2011- 20152, 69% of the population of this region is considered as poor. In this region, the cooking of meals is done on traditional three stones coosktoves, which have a very low energy efficiency. The new project "Promotion of the Wanrou efficient cookstove in the region of Atacora/Donga (ProWAD)”3 4 is included as VPA-2 in the program of activities (PoA) GS2489 "Efficient cookstoves in Benin and Togo" and is implemented by EcoBenin. -

Read More About SDG Bond Framework

1 C1 - Public Natixis Summary FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................... 4 PART I: Benin mobilised for the 2030 Agenda ....................................................................................... 5 1. The basics about the Republic of Benin .......................................................................................... 5 1.1 Political and administrative organisation of Benin ..................................................................... 6 1.2 A predominately young and rural population ............................................................................. 6 1.3 Human development indicators are improving .......................................................................... 8 1.4 Benin’s economic structure ........................................................................................................ 8 1.5 The authorities’ response to the Covid-19 pandemic ................................................................ 9 2. Actions and policies closely anchored to the 2030 Agenda .......................................................... 11 2.1 Actions for taking ownership of the 2030 Agenda ................................................................... 11 2.2 Mobilising institutions and transforming public action to reach the SDGs .............................. -

Comparative Analysis of Diversity and Utilization of Edible Plants in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas in Benin Alcade C Segnon* and Enoch G Achigan-Dako

Segnon and Achigan-Dako Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2014, 10:80 http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/10/1/80 JOURNAL OF ETHNOBIOLOGY AND ETHNOMEDICINE RESEARCH Open Access Comparative analysis of diversity and utilization of edible plants in arid and semi-arid areas in Benin Alcade C Segnon* and Enoch G Achigan-Dako Abstract Background: Agrobiodiversity is said to contribute to the sustainability of agricultural systems and food security. However, how this is achieved especially in smallholder farming systems in arid and semi-arid areas is rarely documented. In this study, we explored two contrasting regions in Benin to investigate how agroecological and socioeconomic contexts shape the diversity and utilization of edible plants in these regions. Methods: Data were collected through focus group discussions in 12 villages with four in Bassila (semi-arid Sudano-Guinean region) and eight in Boukoumbé (arid Sudanian region). Semi-structured interviews were carried out with 180 farmers (90 in each region). Species richness and Shannon-Wiener diversity index were estimated based on presence-absence data obtained from the focus group discussions using species accumulation curves. Results: Our results indicated that 115 species belonging to 48 families and 92 genera were used to address food security. Overall, wild species represent 61% of edible plants collected (60% in the semi-arid area and 54% in the arid area). About 25% of wild edible plants were under domestication. Edible species richness and diversity in the semi-arid area were significantly higher than in the arid area. However, farmers in the arid area have developed advanced resource-conserving practices compared to their counterparts in the semi-arid area where slash-and-burn cultivation is still ongoing, resulting in natural resources degradation and loss of biodiversity. -

Congressional Budget Justification 2015

U.S. AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION Pathways to Prosperity “Making Africa’s Growth Story Real in Grassroots Communities” CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET JUSTIFICATION Fiscal Year 2015 March 31, 2014 Washington, D.C. United States African Development Foundation (This page was intentionally left blank) 2 USADF 2015 CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET JUSTIFICATION United States African Development Foundation THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION WASHINGTON, DC We are pleased to present to the Congress the Administration’s FY 2015 budget justification for the United States African Development Foundation (USADF). The FY 2015 request of $24 million will provide resources to establish new grants in 15 African countries and to support an active portfolio of 350 grants to producer groups engaged in community-based enterprises. USADF is a Federally-funded, public corporation promoting economic development among marginalized populations in Sub-Saharan Africa. USADF impacts 1,500,000 people each year in underserved communities across Africa. Its innovative direct grants program (less than $250,000 per grant) supports sustainable African-originated business solutions that improve food security, generate jobs, and increase family incomes. In addition to making an economic impact in rural populations, USADF’s programs are at the forefront of creating a network of in-country technical service providers with local expertise critical to advancing Africa’s long-term development needs. USADF furthers U.S. priorities by directing small amounts of development resources to disenfranchised groups in hard to reach, sensitive regions across Africa. USADF ensures that critical U.S. development initiatives such as Ending Extreme Poverty, Feed the Future, Power Africa, and the Young African Leaders Initiative reach out to those communities often left out of Africa’s growth story. -

Evaluation of the Genetic Susceptibility to the Metabolic Syndrome by the CAPN10 SNP19 Gene in the Population of South Benin

International Journal of Molecular Biology: Open Access Research Article Open Access Evaluation of the genetic susceptibility to the metabolic syndrome by the CAPN10 SNP19 gene in the population of South Benin Abstract Volume 4 Issue 6 - 2019 Metabolic syndrome is a multifactorial disorder whose etiology is resulting from the Nicodème Worou Chabi,1,2 Basile G interaction between genetic and environmental factors. Calpain 10 (CAPN10) is the first Sognigbé,1 Esther Duéguénon,1 Véronique BT gene associated with type 2 diabetes that has been identified by positional cloning with 1 1 sequencing method. This gene codes for cysteine protease; ubiquitously expressed in all Tinéponanti, Arnaud N Kohonou, Victorien 2 1 tissues, it is involved in the fundamental physiopathological aspects of insulin resistance T Dougnon, Lamine Baba Moussa and insulin secretion of type 2 diabetes. The goal of this study was to evaluate the genetic 1Department of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, University of susceptibility to the metabolic syndrome by the CAPN10 gene in the population of southern Abomey-Calavi, Benin 2 Benin. This study involved apparently healthy individuals’ aged 18 to 80 in four ethnic Laboratory of Research in Applied Biology, Polytechnic School of Abomey-Calavi, University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin groups in southern Benin. It included 74 subjects with metabolic syndrome and 323 non- metabolic syndrome patients who served as controls, with 222 women versus 175 men Correspondence: Nicodème Worou Chabi, Laboratory with an average age of 40.58 ± 14.03 years old. All subjects were genotyped for the SNP of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Department of 19 polymorphism of the CAPN10 gene with the PCR method in order to find associations Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Faculty of Science and between this polymorphism and the metabolic syndrome. -

Governance, Marketing and Innovations in Beninese Pineapple Supply Chains

Governance, marketing and innovations in Beninese pineapple supply chains A survey of smallholder farmers in South Benin Djalalou-Dine Ademonla A. Arinloye Thesis committee Promotors Prof. Dr S.W.F. Omta Professor of Management Studies, Wageningen University Prof. Dr Ir M.A.J.S. van Boekel Professor of Food Quality and Design, Wageningen University Co-promotors Dr J.L.F. Hagelaar Assistant Professor, Management Studies Group, Wageningen University Dr Ir A.R. Linnemann Assistant Professor, Food Quality and Design, Wageningen University Other members Prof. Dr R. Ruben, Radboud University Nijmegen Prof. Dr ir C. Leeuwis, Wageningen University Prof. Dr X. Gellinck, Ghent University, Belgium Dr D. Hounkonnou, Connecting Development Partners (CDP) International, Benin This research was conducted under the auspices of the Wageningen School of Social Sciences (WASS) and the Graduate School VLAG (Advanced studies in Food Technology, Agrobiotechnology, Nutrition and Health Sciences) Governance, marketing and innovations in Beninese pineapple supply chains A survey of smallholder farmers in South Benin Djalalou-Dine Ademonla A. Arinloye Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. dr. M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Thursday 25 April 2013 at 11 a.m. in the Aula. Djalalou-Dine Ademonla A. Arinloye Governance, marketing and innovations in Beninese pineapple supply chains, 194 pages. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2013) With references, with summaries in English and Dutch ISBN: 978-94-6173-534-8 Acknowledgements This thesis represents a continuation of my engagement with empirical research I performed at the Agricultural Policy Analysis Unit of the National Agriculture Research Institute of Benin (PAPA/INRAB) and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). -

CHAPTER II 1. Entry Summaries Page 2

1 CHAPTER I Table of Contents: CHAPTER II 1. Entry summaries Page 2 – 9 CHAPTER III 1. Abjata Khalif: Human trafficking Page10-12 2. Andualem Sisay: Ethiopia‘s crippled agriculture Page 13-15 3. Benjamin Tetteh: At mercy of the sea Page 16-18 4. Bibi-Aisha Wadualla: Religious bias in Egpy‘s universities Page 19-20 5. Deogratius Mmana: How dangerous criminals get out of jail before time to cause more havoc in public Page 21- 23 6. Kassim Mohamed: Pirates: Social bandits in Africa Page 24-27 7. Ken Opala: Lush Mrima Hill may be a death trap for unsuspecting residents Page 28-30 8. Khadija The Great Billion Dollar Drug Scam Page 31 - 35 9. Kipchumba Some: Police killings of youth Page 36-37 10. Muhyadin Ahmed Roble: What it Takes to Cover a Story in Somalia Page 38-40 11. Nicholas Ibekwe: Gowen and Bayero worked for Pfizer Page 41-43 12. Olu Jacob: The Muslim who risked all his Christian neighbours Page 44 -46 13. Patrick Mayoyo: Kenyan firms make killing from piracy Page 47 -48 14. Peter Nkanga: Last minute oil deals that cost Nigeria dear Page 49-52 15. Ramata Sore: Racist coverage of Africa in the US at the time of the World CupPage 53-55 16. Stephen Nartey: Ivorian girls trade sex for food Page 56 - 56 17. Tereza Ndanga: Cashing in on illegal abortions in Malawi Page 57 -58 18. Toyosi Ogunseye: Public school toilets, pits of the death and diseases Page 59 - 62 19. Estacio Valoi: Leaders complicit in the looting of wood in Zambezia Page 63 - 65 20. -

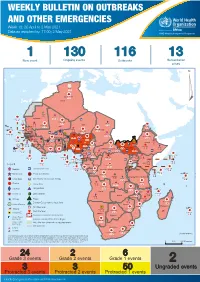

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 18: 26 April to 2 May 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 2 May 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 130 116 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 64 0 122 522 3 270 Algeria ¤ 36 13 612 0 5 901 175 Mauritania 7 2 13 915 489 110 0 7 0 Niger 18 448 455 Mali 3 671 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 828 170 Eritrea Cape Verde 40 433 1 110 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 24 368 224 1 069 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 258 384 3 726 0 165 167 2 063 Guinea 13 319 157 12 3 736 67 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 556 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 52 14 Ghana 70 607 1 064 6 411 88 Côte d'Ivoire 10 583 115 14 484 479 65 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 1 029 2 49 0 97 17 25 0 22 333 268 46 150 287 92 683 779 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 843 20 3 1 160 422 2 763 655 2 91 0 123 12 6 1 488 6 4 057 79 13 010 7 694 112 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 1 0 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 973 342 Kenya Legend 7 821 99 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 310 35 25 253 337 Measles 23 075 139 Democratic Republic of the Congo 11 016 147 Burundi 4 046 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 29 965 768 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 191 0 5 941 26 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 63 1 6 257 229 26 993 602 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 91 693 1 253 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Leishmaniasis 34 096 1 148 862 0 3 840 146 Zambia 133 -

Post-Cairo Reproductive Health Policies and Programs: a Study of Five Francophone African Countries

The POLICY Project Justine Tantchou Ellen Wilson Post-Cairo Reproductive Health Policies and Programs: A Study of Five Francophone African Countries August 2000 Photo Credits All photos are printed with permission from the JHU/Center for Communication Programs. Post-CairoPost-Cairo ReproductiveReproductive HealthHealth PoliciesPolicies andand Programs:Programs: AA StudyStudy ofof FiveFive FrancophoneFrancophone AfricanAfrican CountriesCountries IntroductionIntroduction situation regarding reproductive health. In addition, given that all respondents are Since the ICPD in 1994, reproductive prominent in the reproductive health field, health has been a focus of health programs their perspectives actually influence the worldwide. Many countries have worked development of policies and programs in to revise reproductive health policy in their respective countries. accordance with the ICPD Programme of In each country, two to three members Action. In 1997, POLICY conducted case of the Reproductive Health Research studies in eight countries—Bangladesh, Committee—the country’s local branch of Ghana, India, Jamaica, Jordan, Nepal, RESAR—conducted the study. Research Peru, and Senegal—to examine field teams included at least one medical experiences in developing and specialist and one social science specialist. implementing reproductive health policies. The team carried out the fieldwork for the In 1998, RESAR conducted similar case case studies between October and studies in five Francophone African countries—Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mali. RESAR’s purpose in conducting the studies was not to provide quantitative measurements of reproductive health indicators or an exhaustive inventory of reproductive health laws and policies but to improve understanding of reproductive health policy formulation and implementation. The study was qualitative, drawing on the perspectives of key informants—individuals who play an important role in formulating and implementing reproductive health policies and plans. -

Wilhelms – Universität Bonn Productivity and Water Use Efficie

Institut für Pflanzenernährung der Rheinischen Friedrich – Wilhelms – Universität Bonn Productivity and water use efficiency of important crops in the Upper Oueme Catchment: influence of nutrient limitations, nutrient balances and soil fertility. I n a u g u r a l – D i s s e r t a t i o n zur Erlangung des Grades Doktor der Agrarwissenschaft (Dr. agr.) der Hohen Landwirtschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich – Wilhelms – Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt im September 2005 von Gustave Dieudonné DAGBENONBAKIN aus Porto-Novo, Benin Referent: Prof. Dr. H. Goldbach Korreferent: Prof. Dr. M.J.J. Janssens Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: Dedication ii Dedication This work is dedicated to: Errol D. B. and Perla S. K. DAGBENONBAKIN, Yvonne DOSSOU-DAGBENONBAKIN, Raphaël S. VLAVONOU. Acknowledgments iii Acknowledgements The participation and contribution of individuals and institutions towards the completion of this thesis are greatly acknowledged and indebted. Foremost my sincere appreciation and thankfulness are extended to my promoter Prof. Dr. Heiner Goldbach for providing professional advice, whose sensitivity, patience and fatherly nature have made the completion of this work possible, he always gave freely of his time and knowledge. I would like to express my profound gratitude to Prof. Dr. Ir. Marc Janssens, for giving me the opportunity to pursue my PhD thesis in IMPETUS Project. His insights criticisms are very useful in improving this work. I am grateful to Prof. Dr. H-W. Dehne for reading this thesis and accepting to be the chairman of my defense. My sincere words of thanks are also directed to Prof. Dr. Karl Stahr of the Institute of Soil Science at the University of Hohenheim for giving me the opportunity to be enrolled as PhD student in his Institute.