Benin Assessment and Analysis Report February 15-28, 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benin Case Study

The Impact of U.S. Democracy and Governance Assistance in Africa: Benin Case Study Edward R. McMahon Dean’s Professor of Applied Politics Director, Center on Democratic Performance Department of Political Science Binghamton University (SUNY) Binghamton, New York 13902-6000 Tel: (607) 777-6603 Email: [email protected] Paper Prepared for Presentation at American Political Science Association Meeting in Boston, Massachusetts, August 29 – September 1, 2002 Abstract As part of its support for democratic development around the world, especially since the collapse of communism in the late 1980s, the international community has provided a significant amount of assistance for the promotion of democracy. While there is a modest, albeit growing, amount of literature on this issue, there are few independent analyses on a country basis of the effects of specific donor country democracy assistance. This is an issue of increasing importance as the notion of “good governance,” including representative and transparent political systems, has become a central developmental concept. This paper examines what effect, positive or negative, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) support has had on democratic development in Benin, a key country in the development of democracy in Africa. The paper also presents some thoughts on broader issues concerning the efficacy of democracy assistance. The paper examines USAID efforts to promote democracy in Benin in the rule of law, civil society, elections and political processes, and governance sub-sectors of democracy assistance. The challenge of extrapolating conclusions too broadly from one case study is clear. This paper does conclude, however, that a qualitative analysis of the effectiveness of U.S. -

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

United Nations CCPR/C/BEN/Q/2/Add.1 International Covenant on Distr.: General 24 September 2015 Civil and Political Rights English Original: French English, French and Spanish only Human Rights Committee 115th session 19 October-6 November 2015 Item 5 of the provisional agenda Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 40 of the Covenant List of issues in relation to the second periodic report of Benin Addendum Replies of Benin to the list of issues* [Date received: 21 September 2015] Reply to the questions raised in paragraph 1 1. The Covenant has been an integral part of the legal framework of Benin since 20 September 2006, the date on which it was published in the Official Gazette. It has occasionally been invoked in judicial proceedings by the parties and has been applied by the courts. 2. The various legal instruments ratified by Benin, including the Covenant, have been widely disseminated through the human rights law clinics organized by the Human Rights Directorate of the Ministry of Justice, Legislation and Human Rights. 3. The Covenant has also been disseminated among judges and other law enforcement officials by means of special human rights awareness kits that have been prepared and distributed. Reply to the questions raised in paragraph 2 4. The implementing legislation for Act No. 2012-36 of 15 February 2013 on the establishment of the Benin Human Rights Commission was contained in a decree issued on 6 May 2014. 5. With a view to the start-up of the Commission, the National Assembly adopted decision No. -

Sophie Andreetta and Annalena Kolloch

2017 ARBEITSPAPIER – WORKING PAPER 171 Sophie Andreetta and Annalena Kolloch „On se débrouille“ How to be a good judge when the state lets you down? ARBEITSPAPIERE DES INSTITUTS FÜR ETHNOLOGIE UND AFRIKASTUDIEN WORKING PAPERS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND AFRICAN STUDIES Herausgegeben von / The Working Papers are edited by: Institut für Ethnologie und Afrikastudien, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, Forum 6, D-55099 Mainz, Germany. Tel. +49-6131-3923720; Email: [email protected]; http://www.ifeas.uni-mainz.de http://www.ifeas.uni-mainz.de/92.php Geschäftsführende Herausgeberin / Managing Editor: Konstanze N’Guessan ([email protected]). Copyright remains with the author. Zitierhinweis / Please cite as: Andreetta, Sophie and Annalena Kolloch (2017): “On se débrouille”. How to be a good judge when the state lets you down? Arbeitspapiere des Instituts für Ethnologie und Afrikastudien der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz (Working Papers of the Department of Anthropology and African Studies of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz) 171. Andreetta, Sophie and Annalena Kolloch (2017): “On se débrouille”. How to be a good judge when the state lets you down? Abstract Over the last couple of years, Beninese magistrates have gone on multiple strikes. Most of them complain about their substantial workload, low pay, and poor working conditions. They also highlight the discrepancies between the magistrates’ social status and what their families expect from them. While there seems to be a professional malaise within the Beninese bench, judges and prosecutors also insist on the importance of their work and the ethics that goes together with it. This is why we will be looking at the discourses and representations of the social and professional status of Beninese judges. -

The Role of the Judiciary in the Implementation of the Conventions on the Right of the Child in Benin1

THE ROLE OF THE JUDICIARY IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CONVENTIONS ON THE RIGHT OF THE CHILD IN BENIN1 By Sakinatou BELLO* The State by its commitments to international conventions is free to choose to implement these standards and impose an obligation not only to respect them in its dealings with other parties but also implement them in its own territory2. International Convention on the Rights of the Child, despite its special nature3, is no exception to these general rules of international law. These Conventions, because they essentially place obligations on the State for the benefit of its people, they have no real value unless they are implemented on the territory of the State Party4. Thus, the actual introduction of the Conventions on the Rights of the Child appears as an important first step towards the realization of rights promoted and protected by the beneficiaries. Today, the doctrine and State practice teach us two important trends regarding the introduction of international standards into domestic law: the dualistic and the monistic method. If Sciotti-Lam5 rightly considers that dualism makes it difficult for the validity of international conventions on human rights in domestic law, there is no doubt that the monistic method6 facilitates the effectiveness of the Conventions on human rights in general but even more those relating to child rights7. The monistic theory of the introduction of international standards into domestic law, which advocates for, among others, Krabbe, Leon Duguit, but above all the Austrian school of jurists whose master was Hans Kelsen and torchbearer8, affirms the unity between the international legal order and domestic legal order. -

Annual Progress Report 2016 HER CHOICE Final

ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT 2016 HER CHOICE BUILDING CHILD MARRIAGE FREE COMMUNITIES MAY 2017 BUILDING CHILD MARRIAGE FREE COMMUNITIES Girls and young women are free to decide if, when, and whom to marry 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 4 2. CONTEXT ANALYSIS ............................................................................................................ 4 3. ANALYSIS OF RESULTS ........................................................................................................ 8 3.1. STRATEGY I ....................................................................................................................... 8 3.2. STRATEGY II .................................................................................................................... 10 3.3. STRATEGY III ................................................................................................................... 12 3.4. STRATEGY IV .................................................................................................................. 14 3.5. STRATEGY V ................................................................................................................... 15 3.6. STRATEGY VI .................................................................................................................. 17 3.7. ANALYSIS OF RESULTS ................................................................................................... 18 4. -

CHAPTER II 1. Entry Summaries Page 2

1 CHAPTER I Table of Contents: CHAPTER II 1. Entry summaries Page 2 – 9 CHAPTER III 1. Abjata Khalif: Human trafficking Page10-12 2. Andualem Sisay: Ethiopia‘s crippled agriculture Page 13-15 3. Benjamin Tetteh: At mercy of the sea Page 16-18 4. Bibi-Aisha Wadualla: Religious bias in Egpy‘s universities Page 19-20 5. Deogratius Mmana: How dangerous criminals get out of jail before time to cause more havoc in public Page 21- 23 6. Kassim Mohamed: Pirates: Social bandits in Africa Page 24-27 7. Ken Opala: Lush Mrima Hill may be a death trap for unsuspecting residents Page 28-30 8. Khadija The Great Billion Dollar Drug Scam Page 31 - 35 9. Kipchumba Some: Police killings of youth Page 36-37 10. Muhyadin Ahmed Roble: What it Takes to Cover a Story in Somalia Page 38-40 11. Nicholas Ibekwe: Gowen and Bayero worked for Pfizer Page 41-43 12. Olu Jacob: The Muslim who risked all his Christian neighbours Page 44 -46 13. Patrick Mayoyo: Kenyan firms make killing from piracy Page 47 -48 14. Peter Nkanga: Last minute oil deals that cost Nigeria dear Page 49-52 15. Ramata Sore: Racist coverage of Africa in the US at the time of the World CupPage 53-55 16. Stephen Nartey: Ivorian girls trade sex for food Page 56 - 56 17. Tereza Ndanga: Cashing in on illegal abortions in Malawi Page 57 -58 18. Toyosi Ogunseye: Public school toilets, pits of the death and diseases Page 59 - 62 19. Estacio Valoi: Leaders complicit in the looting of wood in Zambezia Page 63 - 65 20. -

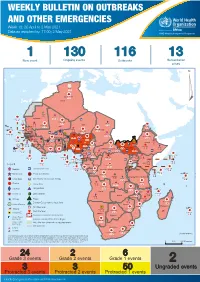

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 18: 26 April to 2 May 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 2 May 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 130 116 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 64 0 122 522 3 270 Algeria ¤ 36 13 612 0 5 901 175 Mauritania 7 2 13 915 489 110 0 7 0 Niger 18 448 455 Mali 3 671 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 828 170 Eritrea Cape Verde 40 433 1 110 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 24 368 224 1 069 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 258 384 3 726 0 165 167 2 063 Guinea 13 319 157 12 3 736 67 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 556 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 52 14 Ghana 70 607 1 064 6 411 88 Côte d'Ivoire 10 583 115 14 484 479 65 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 1 029 2 49 0 97 17 25 0 22 333 268 46 150 287 92 683 779 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 843 20 3 1 160 422 2 763 655 2 91 0 123 12 6 1 488 6 4 057 79 13 010 7 694 112 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 1 0 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 973 342 Kenya Legend 7 821 99 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 310 35 25 253 337 Measles 23 075 139 Democratic Republic of the Congo 11 016 147 Burundi 4 046 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 29 965 768 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 191 0 5 941 26 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 63 1 6 257 229 26 993 602 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 91 693 1 253 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Leishmaniasis 34 096 1 148 862 0 3 840 146 Zambia 133 -

Post-Cairo Reproductive Health Policies and Programs: a Study of Five Francophone African Countries

The POLICY Project Justine Tantchou Ellen Wilson Post-Cairo Reproductive Health Policies and Programs: A Study of Five Francophone African Countries August 2000 Photo Credits All photos are printed with permission from the JHU/Center for Communication Programs. Post-CairoPost-Cairo ReproductiveReproductive HealthHealth PoliciesPolicies andand Programs:Programs: AA StudyStudy ofof FiveFive FrancophoneFrancophone AfricanAfrican CountriesCountries IntroductionIntroduction situation regarding reproductive health. In addition, given that all respondents are Since the ICPD in 1994, reproductive prominent in the reproductive health field, health has been a focus of health programs their perspectives actually influence the worldwide. Many countries have worked development of policies and programs in to revise reproductive health policy in their respective countries. accordance with the ICPD Programme of In each country, two to three members Action. In 1997, POLICY conducted case of the Reproductive Health Research studies in eight countries—Bangladesh, Committee—the country’s local branch of Ghana, India, Jamaica, Jordan, Nepal, RESAR—conducted the study. Research Peru, and Senegal—to examine field teams included at least one medical experiences in developing and specialist and one social science specialist. implementing reproductive health policies. The team carried out the fieldwork for the In 1998, RESAR conducted similar case case studies between October and studies in five Francophone African countries—Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mali. RESAR’s purpose in conducting the studies was not to provide quantitative measurements of reproductive health indicators or an exhaustive inventory of reproductive health laws and policies but to improve understanding of reproductive health policy formulation and implementation. The study was qualitative, drawing on the perspectives of key informants—individuals who play an important role in formulating and implementing reproductive health policies and plans. -

Benin Page 1 of 15

2008 Human Rights Report: Benin Page 1 of 15 2008 Human Rights Report: Benin BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2008 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices February 25, 2009 Benin is a constitutional democracy with a population of 7.9 million. In 2006 President Boni Yayi was elected to a five-year term in multiparty elections. In March 2007 legislative elections, President Yayi's Cowry Force for an Emerging Benin (FCBE) won 35 of 83 seats in the National Assembly and formed a majority with a group of 13 National Assembly members from minor political parties. This coalition proved unstable and at year's end the National Assembly was at a standstill, with the opposition majority group blocking all outstanding bills. International observers viewed both the presidential and legislative elections as generally free and fair. However, municipal and local elections held on April 20 and May 1 were marred by numerous irregularities, protests, and credible allegations of fraud. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces. The government generally respected the human rights of its citizens. However, there were problems in some areas. A blunder by security forces resulted in one death and injuries. There were reports that police occasionally used excessive force. Vigilante violence resulted in deaths and injuries. Harsh prison conditions and arbitrary arrest and detention with prolonged pretrial detention continued. Impunity and corruption were problems. Women were victims of violence and societal discrimination, and female genital mutilation (FGM) was commonly practiced. Trafficking and abuse of children, including infanticide and child labor, occurred. RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: a. -

42 Nd Human Rights Council Session

BIOGRAPHIES OF THE LDCs/SIDS BENEFICIARY DELEGATES AND FELLOWS SUPPORTED BY THE TRUST FUND AT HRC 42 1 ANGOLA Mr. Cabral Laureano Neto (Fellow) 2 BENIN Mr. Randal Oguidan 3 GRENADA Mr. Robert Branch 4 MALAWI Ms. Florencia Chimwemwe Mtingwi 5 MARSHALL ISLANDS Ms. Teri K. Elbon (Fellow) 6 SAINT KITTS AND NEVIS Mr. Sheldon Henry (Fellow) 7 SAINT LUCIA Ms. Zizi Aiyana Pitcairn (Fellow) 8 SURINAME Mr. Jürgen Tjin Liep Shie 9 TANZANIA Ms. Lucy Darabe Diganyeck (Fellow) 10 UGANDA Ms. Mary Namono (Fellow) 11 ZAMBIA Ms. Lois Kapeza 1 Beneficiary Delegates and Fellows HRC 42 Countries of Origin Key for Biographies: Africa Caribbean & Latin America Asia & The Pacific Delegates will be in Geneva: 3 - 27 September 2019 Fellows will be in Geneva: 3 September - 15 November 2019 2 ANGOLA (REPUBLIC OF) Mr. Cabral Laureano Neto Second Secretary Multilateral Affairs Division, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Mr. Cabral Laureano Neto is a diplomat (Second Secretary) within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Angola, posted at the Multilateral Affairs Division in Luanda. Currently Mr. Laureano holds the responsibility of Human Rights Desk at Ministerial level, making him the principal person responsible for human rights. He recently became a member of the Inter-ministerial Commission for the Elaboration of National Reports on Human Rights, under the umbrella of Angola´s Ministry of Justice and Human Rights. This Commission monitors, protects and promotes human rights in the country. He has been a diplomat since 2008, and has vast experience in international relations and diplomacy at both bilateral and multilateral levels. -

(1) BASIC FACTS Independence: 1 August 1960, Former French

BENIN By Roland Adjovi, a PhD student at the University of Paris II, Panthéan-Assas. He taught at the University of Bouaké, Ivory Coast, 1998-1999. (1) BASIC FACTS Independence: 1 August 1960, former French colony, known as Dahomey until 1975 Leader: Mathieu Kerekou, b 1933, president since April 1996 Capital: Porto Novo Other major city: Cotonou (main seaport and international airport) Area: 1 1 2 622 km2 Population: 6,5 mn (1995-2000) Population growth: 2,7 % Urbanization: 34 % (1995-2000) Languages: French (official), Kwa-Fon, Yoruba, Gur-Bariba, Hausa, Mande-Busa HDI rank: 146 (1997) Life expectancy at birth: 54 years ( 1 994) Adult literacy rate: 37 % (1995) Gross enrolment ratio (all educational levels): 35 % (1994) GNP: $2 034 mn GNP/capita: $370 (1995) GDP (average annual growth rate): 4,1 % (1990-95) Foreign debt: $1 646 mn (1995); as % of GNP: 81 % Development aid.� $256 mn (1 995); as % of GNP: 19 % Form of government: Presidential system Highest court dealing with constitutional matters: Constitutional Court (Cour constitutionelle) Tel 31 1610; Fax 313712 (President: Conceptia Ouinsou (since 1998)) Government institutions dealing with human rights: The Department of Human Rights of the Ministry of Justice, Legislation and Human Rights, created in 1997, has as its duty the promotion, popularization and protection of human rights. Within the same Ministry, there are two other departments that also play a role in the protection of human rights: the Department for Legal Protection of Children and Youth and the Department for the Safeguarding of Children. Tel 313146/313147 (Director of Human Rights: Mr Cyrille Oguin) High Authority of Audiovisual and Communications (HAAC - Haute Autorite de l Audiovisuel et de la Communication), instituted by the Constitution of 1990 to ensure, among others, freedom of the press. -

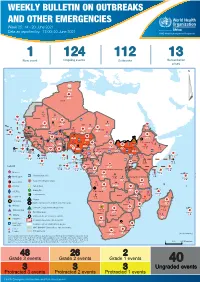

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 25: 14 - 20 June 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 20 June 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 124 112 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 64 0 135 928 3 631 Algeria ¤ 36 13 936 0 6 045 181 Mauritania 14 381 524 48 0 110 0 42 404 1 158 Niger 20 336 481 5 362 19 Mali 21 0 9 0 Cape Verde 6 471 16 4 946 174 Chad Eritrea Senegal 5 469 193 Gambia 3 0 66 0 32 002 283 1 414 8 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 Burkina Faso 236 49 275 194 4 283 167 155 2 117 Guinea 13 469 167 13 0 3 825 69 1 1 30 0 Benin 198 0 Nigeria 1 063 4 6 0 1 0 Ethiopia 13 2 6 995 50 556 5 872 15 Sierra Leone Togo 530 0 80 090 1 310 Ghana 7 139 98 Côte d'Ivoire 10 786 115 19 000 304 68 0 South Sudan 45 0 Liberia 199 2 17 0 Central African Republic 1 308 2 0 25 0 50 14 0 6 738 221 Cameroon 23 450 289 3 0 48 044 308 94 913 793 34 135 194 7 0 56 0 1 347 30 3 1 620 1 178 078 3 437 2 0 168 0 4 816 82 13 721 128 2 0 8 698 120 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 356 0 822 9 Sao Tome and Principe 4 0 2 995 95 71 543 660 Kenya Gabon Legend Congo 2 682 83 305 26 Rwanda 8 140 103 2 362 37 30 048 378 24 736 156 Democratic Republic of the Congo 12 298 161 Burundi Measles 5 242 8 Seychelles 37 809 879 427 0 Humanitarian crisis 536 32 Monkeypox United Republic of Tanzania 197 0 14 549 52 Suspected Drancuculiasis Lassa fever 509 21 63 1 6 257 229 Cholera Yellow fever 37 678 859 129 003 1 644 Comoros Meningitis 304 3 cVDPV2 Angola Malawi Leishmaniasis 34 868 1 168 726 0 3 908 146 Zambia 133 0 COVID-19 Mozambique