Article 177 References to the European Court

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zapachy Damskie

ZAPACHY DAMSKIE 161 HEAT Beyonce 073 DKNY BE DELICIOUS DKNY 151 TOUCH OF PINK Lacoste 107 BOTTEGA VENETA Bott. Veneta 030 NECTAR LOVE DKNY 156 INSPIRATION Lacoste 019 BRUNO BANANI Bruno Banani 061 GREEN TEA E.Arden 131 FAME Lady Gaga 123 MADE FOR WOMEN Bruno Banani 127 5th AVENUE E.Arden 076 MIRACLE Lancome 102 CHRISTINA AGUILERA C. Aguilera 039 DESIRE ME Escada 092 HYPNOSE Lancome 117 212 VIP C.Herrera 047 INTO THE BLUE Escada 101 LA VIE EST BELLE Lancome 160 212 WOMAN C.Herrera 072 BORN IN PARADISE Escada 199 LA VIE EST BELLE L`eclat Lancome 170 212 VIP ROSE C.Herrera 190 MODERN MUSE LE ROUGE Estee Lauder 109 POEME Lancome 183 GOOD GIRL C.Herrera 189 BECAUSE IT` YOU G.Armani 141 TRESOR Lancome 012 DIOR ADDICT C.Dior 010 SENSI G.Armani 175 LA NUIT TRESOR Lancome 044 MIDNIGHT POISON C.Dior 040 EMPORIO DIAMONDS G.Armani 084 ECLAT D’ARPEGE Lanvin 080 DUNE C.Dior 041 ARMANI MANIA G.Armani 001 DAISY Marc Jacobs 082 MISS DIOR CHERIE C.Dior 110 ACQUA DI GIO G.Armani 186 DECADENCE Marc Jacobs 196 MISS DIOR LE PARFUM C.Dior 111 IDOLE G.Armani 035 LOLA Marc Jacobs 093 POISON C.Dior 100 SI PASSIONE G.Armani 063 LE PARFUM Max Mara 116 DOLCE VITA C.Dior 129 SI G.Armani 172 L`EAU Mercedes 145 HYPNOTIC POISON C.Dior 135 ARMANI CODE G.Armani 124 MEXX WOMAN Mexx 159 J’ADORE C.Dior 146 ACQUA DI GIOIA G.Armani 005 JASMINE GLAM Michael Kors 188 J’ADORE IN JOY C.Dior 150 EMPORIO SHE G.Armani 171 SEXY AMBER Michael Kors 176 POISON GIRL C.Dior 053 BOLERO G.Sabatini 104 L’EAU D’ISSEY Miyake 028 DOWNTOWN C.K 090 GABRIELA SABATINI G.Sabatini 011 I LOVE Moschino -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,189,810 B1 Nerushai Et Al

USOO618981 OB1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,189,810 B1 Nerushai et al. (45) Date of Patent: Feb. 20, 2001 (54) METHOD FOR AEROSOLSPRAYING 5,746,354 * 5/1998 Perkins ................................. 222/135 LIQUID PERFUME PRODUCTS 5,772,074 6/1998 Dial et al. ............................ 222/646 (76) Inventors: Sergei Alexeevich Nerushai, Russia, FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS 140000, Moskovskaya oblast, Ljubertsy, 2563 981 11/1985 (FR). Komsomolsky prospekt, Moscow (RU); 2586 913 3/1987 (FR). Nurakhmed Nurislamovich Latypov, 5Voikovsky proezd.d.10, kV.31, Moscow * cited by examiner 125171 (RU) Primary Examiner Andres Kashnikow Assistant Examiner Dinh Q. Nguyen (*) Notice: Under 35 U.S.C. 154(b), the term of this (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Burns, Doane, Swecker & patent shall be extended for 0 days. Mathis, L.L.P. (21) Appl. No.: 09/401,372 (57) ABSTRACT (22) Filed: Sep. 22, 1999 A method for aeroSol Spraying liquid perfume products consists of Simultaneously spraying liquid perfume products (30) Foreign Application Priority Data and/or components of liquid perfume products, having dif Oct. 7, 1998 (RU) ................................................ 98118182 ferent odors, in the form of aeroSol Streams into a region being treated. AeroSol Spraying nozzles are placed proxi (51) Int. Cl." ................................................. A62C 13/62 mate each other. The Simultaneous spraying of at least two (52) U.S. Cl. .......................... 239,306; 239/337; 239/433; components of a liquid perfume product is carried out, and 222/135; 222/402.1 during the Spraying the axes of the aeroSol Streams of the (58) Field of Search ..................................... 239/306, 337, components are positioned at an angle to each other that 239/418, 433, 543, 544; 222/137, 132, ensures interSection of the aeroSol Streams. -

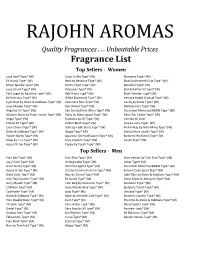

Fragrance List Print

Quality Fragrances . Unbeatable Prices Fragrance List Top Sellers - Women Love Spell Type* (W) Gucci Guilty Type* (W) Romance Type* (W) Ed Hardy Type*RAJOHN (W) Heat by Beyonce Type* (W)AROMASBlack by Kenneth Cole Type* (W) Moon Sparkle Type* (W) Jimmy Choo Type* (W) Beautiful Type* (W) Love Struck Type* (W) Pleasures Type* (W) Bombshell by VS Type* (W) Pink Sugar by Aquolina Type* (W) Reb'l Fleur Type* (W) Black Woman Type* (W) Be Delicious Type* (W) White Diamonds Type* (W) Versace Bright Crystsal Type* (W) Light Blue by Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Cashmere Mist Type* (W) Candy by Prada Type* (W) Issey Miyake Type* (W) Butt Naked Type* (W) Michael Kors Type* (W) Angel by VS Type* (W) Can Can by Paris Hilton Type* (W) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* (W) Modern Muse by Estee Lauder Type* (W) Daisy by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Miss Dior Cherie Type* (W) Angel Type* (W) Euphoria by CK Type* (W) Lick Me All Over Chanel #5 Type* (W) Amber Blush Type* (W) Viva La Juicy Type* (W) Coco Chanel Type* (W) Halle by Halle Berry Type* (W) Pink Friday by Nicki Minaj Type* (W) Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Happy Type* (W) Dot by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Flower Bomb Type* (W) Japanese Cherry Blossom Type* (W) Burberry Weekend Type* (W) Glow by J. Lo Type* (W) Juicy Couture Type* (W) Coach Type* (W) Acqua Di Gio Type* (W) Poppy by Coach Type* (W) Top Sellers - Men Polo Red Type* (M) Polo Blue Type* (M) Grey Vetiver by Tom Ford Type* (M) Jay-Z Gold Type* (M) Unforgivable Type* (M) Usher Type* (M) Gucci Guilty Type* (M) Chrome Legend Type* (M) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* -

Paco Rabanne

HERSTELLER DUFT NR PRODUKTART Aerin Amber Musk 834 PR Aventus Creed 372 P KS Bottega Veneta 819 PR Burberry The Beat 239 P Burberry London 257 P Byredo Bal D´Afrique 709 PR Cacharel Amore Amore 23 P PP PI Calvin Klein Eternity Flame 484 P Euphoria 171 PR DG Deep Euphoria 802 PR Carolina Herrera Good Girl 431 P PP 212 714 PR Cerruti Cerruti 1881 706 P Chanel Coco Mademoiselle 18 P PP PI DG BL DR KS RS No.5 21 P PI No.5 Red Limited Edition 826 PR Chance 34 P PP Chance eau Fraiche 707 PR Chance eau Tendre 322 PR Coco Noir 365 PR Gabrielle 800 PR Chloé L´Eau de Chloe 488 P Love Story 807 PR Nomade 447 P Christina Aguilera Christina Aguillera 237 P Davidoff Cool Water 419 P Dior Addict 142 PR Cherie 80 P Dune 825 PR Hypnotic Poison 173 P PI DG BL DR Jádore 10 P PP PI J´adore In Joy 806 PR Joy 445 P Midnight Poison 286 PR HERSTELLER DUFT NR PRODUKTART Dior Miss Dior Absolute Blooming 427 P Miss Dior 432 P Miss Dior 2017 801 PR Miss Dior Blooming Bouquet 810 PR Miss Dior Rose N´Roses 848 PR NEU Poison Girl 434 P DKNY Be Delicious 81 P PP PI DG BL DR Golden Delicious 443 P Dolce & Gabbana Light Blue 33 P PP PI DG BL DR The One 147 PR 3 L`Imperatrice 701 P Peony 836 PR The Only One 444 P Donna Trussardi Donna 355 PR Elisabeth Arden Green Tea 6 P Ellie Saab Le Parfum 352 PR Emporio Armani Because It´s You 817 PR Diamonds 180 P Escada Moon Sparkle 281 PR Estee Lauder Modern Muse 715 PR Ex Nihilo Fleur Narcotique 708 PR Giorgio Armani Aqua di Gio 7 P Armani Code 101 P PP Mania 177 P My Way 847 PR NEU Si 362 PR Cashmere 438 P Si Intense 804 PR Givenchy -

Aesthetic and Social Constructions of Fragrance

Linguistic and Social Constructions of Fragrance Some Preliminary Thoughts on Entering the Field Moeran, Brian Document Version Final published version Publication date: 2004 License CC BY-NC-ND Citation for published version (APA): Moeran, B. (2004). Linguistic and Social Constructions of Fragrance: Some Preliminary Thoughts on Entering the Field. Link to publication in CBS Research Portal General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us ([email protected]) providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 Department of Intercultural Communication and Management Dalgas Have 15 DK-2000 Frederiksberg Working Paper no 77, 2004 Linguistic and Social Constructions of Fragrance: Some Preliminary Thoughts on Entering the Field Brian Moeran Professor [email protected] 0 Linguistic and Social Constructions of Fragrance: Some Preliminary Thoughts on Entering the Field Brian Moeran Copenhagen Business School [email protected] Absolutely not to be quoted without permission, please Preamble The theoretical discourses devoted to smell reflect a maze of fascinating taboos and mysterious attractions. In present-day Western societies, the sense of smell is undervalued. Scents are highly elusive and often cannot be directly named. Many languages have virtually no vocabulary to describe them, except in terms of the other senses of sight, sound, touch and taste. -

Dior Cosmetics, Fragrances & More Ingredients List

Dior Cosmetics, Fragrances & More Ingredients List 1 Synthetic fluorphlogopite, talc, boron nitriqe, barium sulfate, diphenyl dimethiconeninyl diphenyl dimethicone/silsesquioxane crosspolymer, nylon-12, octylex)decyl stearoyl stearate, magnesium myristate, phenyl trimethicone, acrylates/stbnftyl acrylate/dimeihicone methacrylate copolymer, calcium aluminum borosilicate, pentylene glycol, hdi/trimethylcl hexyllactone crosspolymer, dimethicone, lauroyl lysine, sodium dehydroacetate, silica, hydrogen dimethicone, tin oxide, palmitic acid, magnesium hydroxide n 09384/a. 2 Synthetic fluorphlogopite, dimethicone, talc, diisostearyl malate, methyl methacrylate crosspolymer, petrolatum, mica, trimethylolpropane triethylhexanoate, magnesium myristate, hdi/ppg/ polycaprolactone crosspolymer, sorbitan sesquiisostearate, siuca, trimethylsiloxysilicate, polypropyl, silsesqumane, sodium dehydroacetate, sorbic acid, ethylhexylglycerin, glyceryl caprylate, tocopherol n 09458/a. 3 Dimethicone, mica, talc, diisostearyl malate, synthetic fluorphlogopite, methyl methacrylate crosspolymer, petrolatum, trimethylolpropane triethylhexanoate, magnesium myristate, hdi/ppg/ polycaprolactone crosspolymer, silica, sorbitan sesquiisostearate, trimethylsiloxysilicate, polypropyl- silsesquioxane, sodium dehydroacetate, sorbic acid, lauroyl lysine, ethylhexylglycerin, glyceryl caprylate, tin oxide, tocopherol, n 09451/a. 5 Color Designer All In One Artistry Palette - 4 Dimethicone, talc, calcium sodium borosilicate, silica, No. 208 Navy Design diisostearyl malate, petrolatum, -

Catalogue General Cosma -30 A

1 Permanence Téléphonique: Lundi au jeudi : 9:00 - 13:00 14:00 - 18:00 Franco de port à partir de 250 € (prix net) Vendredi : (Si inférieur, participation de 10 euros) 9:00 - 13:00 14:30 - 17:00 Tel : 01.56.83.84.84 Livraison en 8 jours Fax : 01.47.69.91.19 (jours ouvrables) Mail : [email protected] ATTENTION : Adresse : COSMA CHANGEMENT DE PRIX 15 RUE DES GRANDS PRES 92000 NANTERRE Dorénavant tous nos prix sont TTC Prix déjà remisés sur le catalogue IMPORTANT : Afin de faciliter le traitement de vos commandes Merci d’indiquer votre n° de client et un n° de téléphone portable. Ce catalogue annule et remplace tous les autres tarifs. 2 Sommaire Parfums Femme: 4-27 Parfums Homme: 28-42 Parfums Mixte: 43-44 Eaux de toilette enfant: 44 Produits de beauté : 45-65 Produits de soins pour homme: 66 Le maquillage et les produits complémentaires de parfumerie (lait pour le corps, gel douche, déodorant…) sont fournis à la demande. N’hésitez pas à nous contacter. SOMMAIRE ATTENTION: - Les produits n’ayant pas de code et/ou de prix seront bientôt disponibles. Ils seront mis à jour dans le prochain catalogue. En attendant, si vous en souhaitez, merci de bien noter le descriptif. - Nous vous informons que certaines marques peuvent augmenter leur tarif, nous répercuterons les augmentations de prix en conséquence. - En cas de rupture, nous n’assurons pas la livraison des reliquats - Tous les retours doivent nous parvenir en Remise contre signature ! (Colissimo ou recommandé) Tous nos produits sont arrondis à l’euro inférieur Prix déjà remisés dans le catalogue. -

Christian Dior / Evora

BENELUX-GERECHTSHOF COUR DE JUSTICE BENELUX A 95/4/14 ARREST van 16 december 1998 in de zaak A 95/4 -------------------------- Inzake : Christian Dior N.V. tegen Evora B.V. Procestaal : Nederlands ARRET du 16 décembre 1998 dans l’affaire A 95/4 ----------------------------- En cause : Christian Dior S.A. contre Evora B.V. Langue de la procédure : le néerlandais 2 HET BENELUX-GERECHTSHOF In de zaak A 95/4 1. Gelet op het op 20 oktober 1995 door de Hoge Raad der Nederlanden uitgesproken arrest in de zaak nr. 15.735 van PARFUMS CHRISTIAN DIOR S.A., gevestigd te Parijs, en PARFUMS CHRISTIAN DIOR B.V., gevestigd te Rotterdam, eiseressen tot cassatie (hierna afzonderlijk te noemen : Dior Frankrijk, respectievelijk Dior Nederland en gezamenlijk : Dior), tegen EVORA B.V., gevestigd te Renswoude, verweerster in cassatie (verder te noemen : Evora), waarbij overeenkomstig artikel 6 van het Verdrag betreffende de instelling en het statuut van een Benelux-Gerechtshof aan dit Hof vragen van uitleg van de Eenvormige Beneluxwet op de merken (BMW) worden gesteld; TEN AANZIEN VAN DE FEITEN: 2. Overwegende dat de Hoge Raad de feiten waarop de door het Benelux- Gerechtshof te geven uitleg moet worden toegepast, als volgt heeft omschreven: i) Dior Frankrijk ontwikkelt en produceert verscheidene parfums en andere cosmetische producten die zij onder verschillende merken op de markt brengt. Deze producten hebben een relatief hoge prijs en worden gerekend tot de markt van de luxueuze cosmetische producten. ii) Dior Frankrijk heeft voor de verkoop van haar producten in landen buiten Frankrijk alleenvertegenwoordigers aangesteld; Dior Nederland is in Nederland zulk een alleenvertegenwoordiger. -

TRANSLATION of the FRENCH DOCUMENT De Reference FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2009 Contents

TRANSLATION OF THE FRENCH DOCUMENT DE REFERENCE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2009 Contents LVMH GROUP 1 History 1 Financial higHligHts 2 ExEcutive and SupErvisory BodiEs; Statutory Auditors 5 simpliFiEd organizational cHart 6 BusinEss dEscription 9 MANAGEMENT REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 23 LVMH Group 23 parEnt company: lvmh moEt hennEssy - louis vuitton SA 49 Human rEsourcEs 67 LVMH and the environmEnt 83 REPORT OF THE CHAIRMAN OF BOARD OF DIRECTORS 97 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 109 consolidatEd financial statEmEnts 109 parEnt company financial statEmEnts: lvmh moEt hennEssy - louis vuitton sa 179 OTHER INFORMATION 205 corporate govErnancE 205 GenEral inFormation rEgarding the parEnt company; stock markEt inFormation 233 Resolutions for the approval of the combined shareholders’ meeting of April 15, 2010 241 RESPONSIBLE COMPANY OFFICER; FINANCIAL INFORMATION 247 TABLES OF CONCORDANCE 251 This document is a free translation into English of the original French “Document de Référence”, hereafter referred to as the “Reference Document”. It is not a binding document. In the event of a conflict in interpretation, reference should be made to the French version, which is the authentic text. LVMH group HistoRy Although the history of the LVMH Group began in 1987 with the merger of Moët Hennessy and Louis Vuitton, the roots of the Group actually stretch back much further, to eighteenth-century Champagne, when a man named Claude Moët decided to build on the work of Dom Pérignon, a contemporary of Louis XIV; and to nineteenth-century Paris, famous for its imperial celebrations, where Louis Vuitton, a craftsman trunk-maker, invented modern luggage. Today, the LVMH Group is the world’s leading luxury goods company, the result of successive alliances among companies that, from generation to generation, have successfully combined traditions of excellence and creative passion with a cosmopolitan flair and a spirit of conquest. -

OPINION of ADVOCATE GENERAL JACOBS Delivered on 29 April 1997 *

OPINION OF MR JACOBS — CASE C-337/95 OPINION OF ADVOCATE GENERAL JACOBS delivered on 29 April 1997 * 1. The essential question in the present case condition that those retailers supply only to is whether a trade mark proprietor may rely ultimate consumers or other selected upon his trade mark rights to prevent the retailers. advertising of goods placed on the market by him or with his consent, in circumstances in which such advertising damages the luxuri ous and prestigious image of his mark. In particular, is the prevention of such advertis ing possible if the reseller is merely advertis ing in a manner customary to his trade? The 3. Dior France has exclusive rights in the case comes by way of a preliminary refer Benelux to the Eau Sauvage, Poison, Fahren ence from the Hoge Raad der Nederlanden heit and Dune picture trade marks, inter alia (Supreme Court of the Netherlands). for class 3 products including perfumes. Those marks consist of illustrations of the packaging in which the bottles containing the perfumes bearing those names are sold. In addition, Dior France has copyright in both that packaging and those bottles and in Facts and procedure before the national the packaging and bottles of products mar court keted under the name of Svelte. 4. The defendant, Evora BV ('Evora'), oper 2. The second plaintiff, Parfums Christian ates a chain of shops under the name of its Dior ('Dior Netherlands'), is the sole repre subsidiary Kruidvat. Those shops are sentative in the Netherlands of the first described in the order for reference as chem plaintiff, Parfums Christian Dior SA ('Dior ists' shops. -

Perfume List

Ladies Perfume Ladies Perfume Inspiration House Our name Inspiration House Our name 212 Caroline Herrera Charlene Si Giorgio Armani Cindy 212 VIP Caroline Herrera Alexandra Si Intense Giorgio Armani Lindy 5th Avenue Elizabeth Arden Eliza Spellbound Estee Lauder Natasja Addict Christian Dior Nadine Tabasheer Avon Tamara Alien Thierry Mugler Alena Tabu Dana Talita Amarige Givenchy Amour Tender Poison Christian Dior Tender Passion Amor Amor Cacherel Amy The One Dolce & Gabanna Cheryl Angel Thierry Mugler Celestial Tommy Girl Tommy Hillfiger Tammy Angel & Demons Givenchy Angelina Touch Of Pink Lacosté Lucy Annaїs Annaїs Cacherel Anne White Diamonds Elizabeth Taylor Glitter Armani Diamonds Giorgio Armani Dazzle White Linen Estee Lauder Tiki Aromatics Clinique Saladin White Musk Jovan Joselyn Armotaics White Clinique Katy Youth Dew Estee Lauder Denise Be Delicious (DKNY) Donna Karen Deliah Beautiful Estee Lauder Beatrice Black Opium Yves Saint Laurent Paradisio Men's Perfume Black Orchid Tom Ford Anthea Inspiration House Our name Black XS L’Exces Paco Rabanne Lily 212 Caroline Herrera Charlie Bulgari Bulgari Bernice 212 VIP Caroline Herrera Alexander Candy Prada Candice Amen Thierry Mugler Apollo Chanel No:5 Chanel Chani Antonio Antonio Banderos Tony Chloe Chloe Claire Aramis Aramis Icarus Cinnabar Estee Lauder Zanzi Aramis 900 Aramis Athos Coco Mademoiselle Chanel Cara Armani Code Giorgio Armani Mario Copellia Avroy Shlain Danté Black Ferrari Ferrari Antonio Curious Britney Spears Fantasia Pink Black XS Paco Rabanne Enrique DKNY Donna Karen -

Of Natural Raw Materials of Plant Origin

Natural raw materials Introduction English Classifications of natural raw materials of plant origin Clove tree Fennel Coriander Parsley Sandalwood Nutmeg Lemon tree Perfume manufacturers classify natural raw materials of plant origin according to their own specific system. The International Perfume Museum has chosen the classification system used by perfume designer Jean-Claude Ellena, creative director at Hermès perfumes. But there are others. Used as working tool by the perfumer and perfume technicians for designing a new composition, each system is based on a choice of raw materials that reflects different eras and graphic fashions. Classification of smells from a botanical viewpoint by families Certain authors have attempted to classify smells by botanical families, but this is a utopian undertaking. If we examine the cruciferae family, which is by far the most homogeneous because of its typical sulphured essential oils, we nevertheless find exceptions. Clove tree flowers, for example, have a pleasant rose-caryophyllene aroma that is nothing like the sulphurous aroma of the other cruciferae. Furthermore, simple botanical varieties, such as lilum, nymphea, citrus and cinnamorum, can have scents that are totally different. It would thus seem more logical to indicate only the customary botanical order and the families that supply aromatic plants, as Engler, Gildemeister and F. Hoffmann (1) have done. In Engler’s classification, which is not reproduced here, each aromatic plant is defined by: Branch Celery Rockrose Class Order Family Type Species. Natural raw materials Introduction English Practical classification of smells Another Classification by Smell by tonality or near tonality In spite of the widespread use of perfumes among the ancient I.