Emotional Tone of Viral Advertising and Its Effect on Forwarding Intentions and Attitudes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title Analyzing the Popularity of Youtube Videos That Violate Mountain Gorilla Tourism Regulations Author(S) Otsuka, Ryoma; Yama

Analyzing the popularity of YouTube videos that Title violate�mountain gorilla tourism regulations Author(s) Otsuka, Ryoma; Yamakoshi, Gen Citation PLOS ONE (2020), 15(5) Issue Date 2020-05-21 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/251074 © 2020 Otsuka, Yamakoshi. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Right Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University PLOS ONE RESEARCH ARTICLE Analyzing the popularity of YouTube videos that violate mountain gorilla tourism regulations Ryoma OtsukaID*, Gen Yamakoshi Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 a1111111111 Although ecotourism is expected to be compatible with conservation, it often imposes nega- tive effects on wildlife. The ecotourism of endangered mountain gorillas has attracted many tourists and functioned as a key component of their conservation. There might be expecta- tions on the part of tourists to observe or interact with gorillas in close proximity and such OPEN ACCESS expectations may have been engendered by the contents of social media in this Information Age. However, the risk of disease transmission between humans and gorillas is a large con- Citation: Otsuka R, Yamakoshi G (2020) Analyzing the popularity of YouTube videos that cern and it is important to maintain a certain distance while observing gorillas to minimize violate mountain gorilla tourism regulations. PLoS risk. We conducted a content analysis and described the general characteristics of 282 You- ONE 15(5): e0232085. -

ITV on Track to Deliver

Interim Results 2017 ITV plc ITV on track to deliver Interim results for the six months to 30 June 2017 Peter Bazalgette, ITV Executive Chairman, said: “ITV’s performance in the first six months of the year is very much as we anticipated and our guidance for the full year remains unchanged. “Total external revenue was down 3% with the decline in NAR partly offset by continued good growth in non-advertising revenues, which is a clear indication that our strategy of rebalancing the business is working. We are confident in the underlying strength of the business as we continue to invest both organically and through acquisitions. “ITV Studios total revenues grew 7% to £697m including currency benefit. ITV Studios adjusted EBITA was down 9% at £110m. This was impacted by our ongoing investment in our US scripted business and the fact that the prior year includes the full benefit of the four year license deal for The Voice of China. We have a very strong pipeline of new and returning drama and formats and we are building momentum in our US scripted business. We continue to grow our global family of production companies and in H1 we further strengthened our international drama and format business with the acquisition of Line of Duty producer World Productions in the UK, Tetra Media Studio in France and Elk Production in Sweden. “The Broadcast business remains robust despite the 8% decline in NAR caused by ongoing economic and political uncertainty with Broadcast & Online adjusted EBITA down 8% at £293m. On-screen we are performing well. -

NANS' CHOCOLATE FUDGE CAKE Ingredients Method

NANS’ CHOCOLATE FUDGE CAKE So this is my baking inspiration and one of first and very vivid food memo- ries. Nans used to make this cake for me and my sister’s birthdays every year and never failed to disappoint. Relatively simple in all accounts, but every time I make it now, I am instantly transported back in memory to making it with her in her small kitchen, not quite reaching the top of the worktop, but always wanting to beat the batter, lick the spoon and of course make the icing and deco- rate with chocolate buttons…Sorry Nans, couldn’t bring myself to put chocolate buttons on my one, but hope you like the shavings – it brings back so many wonderful memories. Method Ingredients FOR THE CAKE 1 Preheat the oven to 180C (350F) Gas 4. In a small bowl combine the cocoa with 5 tablespoons boiling water and mix 50 g cocoa until smooth. Cream the softened butter with both sugars 200 g unsalted butter, softened, plus in a free-standing mixer for 3-4 minutes until pale and light. extra for greasing tins Scrape down the bowl with a rubber spatula, add the eggs 150 g caster sugar one at a time, mixing well between each addition. Add the 125 g soft light brown sugar vanilla extract and mix again until combined. 4 medium eggs 1 teaspoon vanilla extract 2 Sift the flour, baking powder, bicarbonate of soda and a 250 g plain flour pinch of salt into the bowl. Add the cocoa paste and milk and 1 ½ teaspoons baking powder beat again until smooth and thoroughly combined. -

Research Project Report (Bba-2603)

RESEARCH PROJECT REPORT (BBA-2603) On “TO STUDY CONSUMER PREFRENCE OF NESTLE KIT KAT WITH THE RESPECT TO CADBURY DAIRY MILK IN LUCKNOW” Towards partial fulfillment of Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA) (BBD University Lucknow) GUIDED BY SUBBMITTED BY Ms. Pankhuri Shrivastava Aman Singh Asst. Professor (BBDU) School of management Session 2018-2019 School of Management Baba Banarasi Das University Faizabad Road Lucknow (U.P.) India 1 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the Project Report entitled “TO STUDY CONSUMER PREFRENCE OF NESTLE KIT KAT WITH THE RESPECT TO CADBURY DAIRY MILK IN LUCKNOW” submitted by Aman Singh, student of Bachelors of Business Administration (BBA) - Babu Banarasi Das University is a record of work done under my supervision. This is also to certify that this report is an original project submitted as a part of the curriculum and no unfair means like copying have been used for its completion. All references have been duly acknowledged. Ms. Pankhuri Shrivastava 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Survey is an excellent tool for learning and exploration. No classroom routine can substitute which is possible while working in real situations. Application of theoretical knowledge to practical situations is the bonanzas of this survey. We would like thank PANKHURI SHRIVASTAVA for giving us an opportunity and proper guidance to make market research project and the errors be Make curing the research and we would work to improve the some. We also thank the University for conducting such research project in our curriculum which will help us in future. Above all I shall thank my friend who constantly encouraged and blessed me so as to enable me to do this work successfully. -

2005 – Building for the Future

2005 – 2006 2005 – Building for the future Working with communities is an important part of ZSL’s effort to involve local people in the welfare of their wildlife Reading this year’s Living Conservation report I am struck by the sheer breadth and vitality of ZSL’s conservation work around the world. It is also extremely gratifying to observe so many successes, ranging from our international animal conservation and scientific research programmes to our breeding of endangered animals and educational projects. Equally rewarding was our growing Zoology at the University of financial strength during 2005. In a year Cambridge. This successful overshadowed by the terrorist attacks collaboration with our Institute of in the capital, ZSL has been able to Zoology has generated numerous demonstrate solid and sustained programmes of research. We are financial growth, with revenue from our delighted that this partnership will website, retailing, catering and business continue for another five years. development operations all up on last Our research projects continued to year. influence policy in some of the world’s In this year’s report we have tried to leading conservation fields, including give greater insight into some of our the trade in bushmeat, the assessment most exciting conservation programmes of globally threatened species, disease – a difficult task given there are so risks to wildlife, and the ecology and many. Fortunately, you can learn more behaviour of our important native about our work on our award-winning* species. website www.zsl.org (*Best Website – At Regent’s Park we opened another Visit London Awards November 2005). two new-look enclosures. -

George Augustus Sala: the Daily Telegraph's Greatest Special

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. George Augustus Sala: The Daily Telegraph’s Greatest Special Correspondent Peter Blake University of Brighton Various source media, The Telegraph Historical Archive 1855-2000 EMPOWER™ RESEARCH Early Years locked himself out of his flat and was forced to wander the streets of London all night with nine pence in his The young George Augustus Sala was a precocious pocket. He only found shelter at seven o’clock the literary talent. In 1841, at the age of 13, he wrote his following morning. The resulting article he wrote from first novel entitled Jemmy Jenkins; or the Adventures of a this experience is constructed around his inability to Sweep. The following year he produced his second find a place to sleep, the hardship of life on the streets extended piece of fiction, Gerald Moreland; Or, the of the capital and the subsequent social commentary Forged Will (1842). Although these works were this entailed. While deliberating which journal might unpublished, Sala clearly possessed a considerable accept the article, Sala remembered a connection he literary ability and his vocabulary was enhanced by his and his mother had shared with Charles Dickens. In devouring of the Penny Dreadfuls of the period, along 1837 his mother had been understudy at the St James’s with the ‘Newgate novels’ then in vogue, and Theatre in The Village Coquettes, an operetta written by newspapers like The Times and illustrated newspapers Dickens and composed by John Hullah. Madame Sala and journals like the Illustrated London News and and Dickens went on to become good friends on the Punch. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

ITV , Item 2. PDF 378 KB

National Assembly for Wales Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee Briefing note 10 October 2019 ITV is a cornerstone of popular culture in homes across Wales. It is a significant employer with some four hundred staff operating from ten locations right across Wales, making around eight hundred hours of television a year. It retains substantial viewership for television content made in Wales for Wales while also growing audiences of scale for public service news and current affairs content online and across social media. It brings the nation together around important events - as we are currently seeing with the Rugby World Cup - broadcast free-to-air across ITV. As a UK-based commercial business ITV pays tax on its profits here and its employees spend their wages here. It grows brands in Wales, offering trusted and cost effective advertising platforms to government, public bodies and commercial enterprises. It works in partnership with the National Assembly, the Welsh Government and a wide range of commercial and third sector organisations to celebrate the best of Welsh life while providing plurality of coverage in both English and Welsh across news, current affairs, factual and children’s programming. It is a strong supporter of apprenticeship programmes and many other initiatives which are designed to support and encourage diversity and inclusivity. 1 KEY HIGHLIGHTS ● ITV broadcast three of the top five most popular tv programmes in Wales in 2018 (I’m a Celebrity, World Cup: Croatia v England, Six Nations England v Wales). A fourth of the top five (Bodyguard) was made by an ITV company for the BBC. -

February 2Nd 2015

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Coyote Chronicle (1984-) Arthur E. Nelson University Archives 2-2-2015 February 2nd 2015 CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/coyote-chronicle Recommended Citation CSUSB, "February 2nd 2015" (2015). Coyote Chronicle (1984-). 130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/coyote-chronicle/130 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coyote Chronicle (1984-) by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INDEPENDENT STUDENT VOICE OF CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SAN BERNARDINO SINCE 1965 CCoyoteoyote ChronicleChronicle COYOTECHRONICLE.NETNET Vol.VlLIN LI, No. 3 MONDAY,MONDAY FEBRUARY FE 2, 2015 MyCoyote upgrade: The lives of Black Butterfl y cast Men’s basketball on yes or no?, pg. 5 fellow Coyotes, pg. 8 ascends, pg. 11 the rise, pg. 15 CCBriefs: By MARVIN GARCIA Staff Writer From boiled to unboiled (Jan. 23) Researchers at UC Irvine have found a way to reverse a hard-boiled egg to its original state. According to ChemBioChem, a peer-reviewed chemical biology journal, this is an innovation that could reduce costs for cancer treatment, food produc- tion and other segments of the $160 bil- lion global biotechnology industry. For example, there will be further research on protein production, pharma- ceutical companies will be able to ad- vance in cancer antibody development CSUSB community service by reforming proteins, and farmers will able to achieve more bang for their buck. -

1 Decision Science

1 Decision Science Understanding the Why of Consumer Behaviour In marketing our goal is to infl uence purchase decisions. But what drives those decisions? Decision sciences help to answer this crucial question by uncovering the underlying mechanisms, rules and principles of decision making. These fascinating and valuable insights from science have been expanding rapidly in the past few years. This chapter will go into some of the depths of the latest learnings from decision science, but don ’ t worry, you don ’ t need to be a scientist to swim here! We will see what really drives purchasing behaviour, and how to apply these insights to maximize the benefi t to marketing. Most importantly, we will introduce a practical frameworkCOPYRIGHTED to harness the learnings MATERIAL in our everyday marketing roles. cc01.indd01.indd 1 11/3/2013/3/2013 110:53:330:53:33 AAMM Let there be light! No advert in recent times has won more prizes for creativity or received more public and media attention than Cadbury ’ s ‘Gorilla’. Brand volumes had been fairly static for years and the brand had suffered the effects of a signi cant quality problem the previous year. So Cadbury’ s objective was to get back into the British public ’ s ‘hearts and minds’ with a new advert. The agency ’ s brief was to ‘rediscover the joy’. This resulted in the ‘Gorilla’ advert, in which a gorilla rst anticipates and then starts drum- ming along to the Phil Collins song ‘In the air tonight’. The advert achieved huge amounts of interest and attention, not only from consumers but also from those of us working in brand management. -

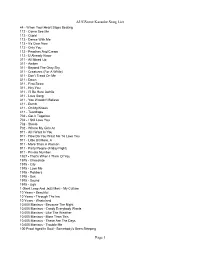

Augsome Karaoke Song List Page 1

AUGSome Karaoke Song List 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 112 - Come See Me 112 - Cupid 112 - Dance With Me 112 - It's Over Now 112 - Only You 112 - Peaches And Cream 112 - U Already Know 311 - All Mixed Up 311 - Amber 311 - Beyond The Gray Sky 311 - Creatures (For A While) 311 - Don't Tread On Me 311 - Down 311 - First Straw 311 - Hey You 311 - I'll Be Here Awhile 311 - Love Song 311 - You Wouldn't Believe 411 - Dumb 411 - On My Knees 411 - Teardrops 702 - Get It Together 702 - I Still Love You 702 - Steelo 702 - Where My Girls At 911 - All I Want Is You 911 - How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 - Little Bit More, A 911 - More Than A Woman 911 - Party People (Friday Night) 911 - Private Number 1927 - That's When I Think Of You 1975 - Chocolate 1975 - City 1975 - Love Me 1975 - Robbers 1975 - Sex 1975 - Sound 1975 - Ugh 1 Giant Leap And Jazz Maxi - My Culture 10 Years - Beautiful 10 Years - Through The Iris 10 Years - Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs - Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs - Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs - Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This 10,000 Maniacs - These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs - Trouble Me 100 Proof Aged In Soul - Somebody's Been Sleeping Page 1 AUGSome Karaoke Song List 101 Dalmations - Cruella de Vil 10Cc - Donna 10Cc - Dreadlock Holiday 10Cc - I'm Mandy 10Cc - I'm Not In Love 10Cc - Rubber Bullets 10Cc - Things We Do For Love, The 10Cc - Wall Street Shuffle 112 And Ludacris - Hot And Wet 12 Gauge - Dunkie Butt 12 Stones - Crash 12 Stones - We Are One 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

CADBURY 2017 Fact Sheet

2017 Fact Sheet One of the World’s Favorite Chocolate Brands Cadbury chocolate is one of the world’s best-selling brands, with more than $3 billion in net revenues in 2016. But it didn’t become one of the world’s favorite chocolate brands overnight. It has a rich and delicious history spanning nearly 200 years, when John Cadbury opened a grocery shop in 1824 in Birmingham, U.K., selling, among other things, cocoa and drinking chocolate. We sold our first chocolate bar in 1847, our iconic Cadbury Dairy Milk was born in 1905… and we’ve been creating delicious chocolate innovations ever since! CADBURY Fun Facts: BIRTH BIGGEST MARKETS 1824 – when John Cadbury opens a grocer’s U.K., Australia, India and China. shop at 93 Bull Street, Birmingham. Among other things, he sold cocoa and drinking chocolate, which he prepared himself using a pestle and mortar. SALES RECENT COUNTRY LAUNCHES Cadbury chocolate generated more than $3 Cadbury 5Star and Cadbury Dairy Milk billion in global net revenues in 2016. OREO in various AMEA markets (2015), Cadbury Fuse in India (2016), Cadbury Dark Milk in Australia (2017). CADBURY FANS GLOBAL REACH Cadbury has nearly 1 million Facebook Cadbury chocolate can be found in more than fans, Cadbury Dairy Milk brand boasts 40 countries. more than 15 million and Cadbury Dairy Milk Silk more than 5 million! MANUFACTURING Cadbury chocolate is manufactured in more than 15 countries around the world. 2017 Fact Sheet Flavors Around the World Cadbury Dairy Milk Launched in 1905 and an instant success! Made with fresh milk from the British Isles and Fairtrade cocoa beans, Cadbury Dairy Milk remains one of the world’s top chocolate products.