Questioning "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction": a Stroll Around the Louvre After Reading Benjamin0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year of Le Nôtre

ch VER ât Sail ecouverture conférence de presse version déf.indd 1 aules 18/01/2012 13:01:48 3 CONTENTS Press conference - 26 january 2012 Foreword 4 Versailles on the move 7 The exhibitions in versailles 8 Versailles to arras 12 Events 13 Shows 15 Versailles rediscovered 19 Refurnishing versailles 21 What the rooms were used for 26 Versailles and its research centre 28 Versailles for all 31 2011, Better knowledge of the visitors to versailles 32 A better welcome, more information 34 Winning the loyalty of visitors 40 Versailles under construction 42 The development plan 43 Safeguarding and developing our heritage 48 More on versailles 60 Budget 61 Developing and enhancing the brand 63 Sponsors of versailles 64 Versailles in figures 65 Appendices 67 Background of the palace of versailles 68 Versailles in brief 70 Sponsors of the palace of versailles 72 List of the acquisitions 74 Advice for visitors 78 Contacts 80 4 Foreword This is the first time since I was appointed the effects of the work programme of the first phase President of the Public Establishment of the Palace, of the “Grand Versailles” development plan will be Museum and National Estate of Versailles that I considerable. But the creation of this gallery which have had the pleasure of meeting the press. will present the transformations of the estate since Flanked by the team that marks the continuity Louis XIII built his hunting lodge here marks our and the solidity of this institution, I will review the determination to provide better reception facilities remarkable results of 2011 and, above all, the major for our constantly growing numbers of visitors by projects of the year ahead of us. -

Gods and Heroes: the Influence of the Classical World on Art in the 17Th & 18Th Centuries

12/09/2017 Cycladic Figure c 2500 BC Minoan Bull Leaper c 1500 BC Gods and Heroes: the Influence of the Classical World on Art in the 17th & 18th centuries Sophia Schliemann wearing “Helen’s Jewellery” Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk Heracles from the Parthenon Paris and Helen krater c 700 BC Roman copy of Hellenistic bust of Homer Small bronze statue of Alexander the Great c 100 BC Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk Judgement of Paris from Etruria c 550 BC Tiberius sword hilt showing Augustus as Jupiter Arrival of Aeneas in Italy Blacas Cameo showing Augustus with aegis breastplate Augustus of Prima Porta c 25 AD Dr William Sterling (discovered 1863) Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk 1 12/09/2017 Romulus and Remus on the Franks Casket c 700 AD Siege of Jerusalem from the Franks Casket Mantegna Triumph of Caesar Mantua c 1490 Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry c 1410 – tapestry of Trojan War Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk The Colosseum Rome The Parthenon Athens The Pantheon Rome Artist’s Impression of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus showing surviving sculpture Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk Hera and Zeus on the Parthenon Frieze in the British Museum Hermes, Dionysus, Demeter and Ares on the Parthenon Frieze Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk -

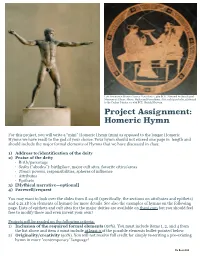

Myth Homeric Hymn Assignment

Left: Artemision Bronze (Zeus or Poseidon). c. 460 BCE. National Archaeological Museum of Athens. Above: Hades and Persephone. Attic red figure kylix, attributed to the Codrus Painter. ca. 430 BCE. British Museum Project Assignment: Homeric Hymn For this project, you will write a “mini” Homeric Hymn (mini as opposed to the longer Homeric Hymns we have read) to the god of your choice. Your hymn should not exceed one page in length and should include the major formal elements of Hymns that we have discussed in class: 1) Address to/identification of the deity 2) Praise of the deity • Birth/parentage • Sedes (“abodes”): birthplace, major cult sites, favorite cities/areas • Timai: powers, responsibilities, spheres of influence • Attributes • Epithets 3) [Mythical narrative—optional] 4) Farewell/request You may want to look over the slides from 8.24.18 (specifically, the sections on attributes and epithets) and 9.21.18 (on elements of hymns) for more details. See also the examples of hymns on the following page. Lists of epithets and cult sites for the major deities are available on theoi.com but you should feel free to modify these and even invent your own! Projects will be graded on the following criteria: 1) Inclusion of the required formal elements (50%). You must include items 1, 2, and 4 from the list above and item 2 must include at least 3 of the possible elements bullet-pointed below. 2) Originality/creativity (50%). You will not receive full credit for simply re-writing a pre-existing hymn in more “contemporary” language! Below are some examples of “real” Homeric Hymns. -

Art Hand-Book, Sculpture, Architecture, Painting

:. •'t-o^ * ^^' v^^ ^ ^^^^\ ^^.m <. .*^ .. X 0° 0^ \D^ *'ir.s^ A < V ^^; .HO^ 4 o *^,'^:^'*.^*'^ "<v*-^-%o-' 'V^^''\/^ V*^^'%^ V\^ o '^^ o'/vT^^^ll^"" vy:. -rb^ ^oVv^'' '^J^M^^r^^ ^^jl.^0'rSi' ^oK °<<. ^""^^ • Sculpture » Architecture * Painting Official H^NDBOOKo/ARCHITECTVRE and SCULPTURE and ART CATALOGUE TO THE Pan-American Exposition With Maps and Illustrations by -permission of C. D. Arnold, Official Photographer BUFFALO, NEW YORK, U. S. A., MAT FIRST TO NOVEMBER FIRST, M. CM. & I. Published by DAVID GRAY, Buffalo, N. Y. Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1901, by David Gray, in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. • • • • • e • • •• V. • » » « » . f>t • •_••» »'t»» » » » * • • . CONGRESS, Two Copiea Received JUN. 17 1901 Copyright entry EXPOSITION, 1901. CLASS ^XXc N». PAN-AMERICAN Buffalo, N. Y. , U. S. A COPY 3, Office of Director-General. March 30, 1901. To whom it may concern: — Mr. David Gray of this City has "been granted hy the Exposition a concession to publish the Art Catalogue of the Exposition^ which will he a hook in reality a memorial of the ideals of the Exposition in Archi- tecture, Sculpture and Pine Arts. WILLIAM I. BUCHANAN, Director-General The articles, pictures and catalogue descriptions in the Pan-American Art Hand Book are copyrighted, and publication thereof without permission is forbidden. \ r..k^ ^'««- -^ -"^^ ^^ This Art Hand Book was made by the publishing and printing house of ISAAC H,. BLANCHARD CO,, in the city of New Torky at 268 and 270 Canal Street, * 200 feet, iij9 inches east of Broadway. -

A Statue of Aphrodite in the Royal Ontario Museum

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 A Statue of Aphrodite in the Royal Ontario Museum Cornelia G. Harcum To cite this article: Cornelia G. Harcum (1921) A Statue of Aphrodite in the Royal Ontario Museum, The Art Bulletin, 4:2, 45-58, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.1921.11409714 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00043079.1921.11409714 Published online: 22 Dec 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Download by: [Nanyang Technological University] Date: 09 May 2016, At: 01:43 Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 01:43 09 May 2016 '\'O HO S T O , \{ O YAI .OS T AH( O :'II u. ·n:u ~ ( 0'" ,\ 11 ( '11,1-:0 1.0 <:\': r .: s us TIn: :'\IOTIIEII A Statue of Aphrodite in the Royal On tario Museum By CORNELIA G. HARCUM IN 1909 the Royal Ontario Museum of Archreology acquired a Parian marble statue, which came originally from the mainland of Greece, and with its basis is just six feet high. It was presented to the museum by Sigmund Samuel, Esq. The woman, or goddess (PI. IX), stands majestically with weight resting on her right foot, her right hip projecting, her left knee bent and slightly advanced. She looks in the direction of the free foot. The position gives the impression of perfect repose yet of the possibility of perfect freedom and ease of motion. -

To Theo Van Gogh. Arles, Tuesday, 18 September 1888

To Theo van Gogh. Arles, Tuesday, 18 September 1888. Tuesday, 18 September 1888 Metadata Source status: Original manuscript Location: Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, inv. nos. b583 a-b V/1962 Date: The letter was written the same day as the previous one to Theo (l. 1*), so we have dated it Tuesday, 18 September 1888. See further the notes to letter 682, Date. Additional: Original [1r:1] Mon cher Theo, ce matin de bonne heure je tai dej crit1 puis je suis all continuer un tableau de jardin ensoleill.2 Puis je lai rentr et suis ressorti avec une toile blanche et celle l aussi est faite.3 Et maintenant jai encore envie de tecrire encore une fois. Parceque jamais jai eu une telle chance, ici la nature est extraordinairement belle. Tout et partout. La coupole du ciel est dun bleu admirable, le soleil a un rayonnement de souffre ple et cest doux et charmant comme la combinaison des bleus celestes et des jaunes dans les Van der Meer de Delft. Je ne peux pas peindre aussi beau que cela mais cela mabsorbe tant, que je me laisse aller sans penser aucune rgle. 1 This was letter 682. 2 Path in the public garden (F 470 / JH 1582); see letter 682. 3 Path in the public garden (F 471 / JH 1613). Van Gogh describes this painting later in the letter. 1 2 To Theo van Gogh. Arles, Tuesday, 18 September 1888. Cela me fait 3 tableaux des jardins en face de ma maison.4 Puis les deux cafs. 5 Puis les tournesols. -

Une Certain Équivoque? a Study of Vincent Van Gogh's Ambivalent Engagement with Prostitution, Highlighted by the 1888 Courrier Français Censorship Controversy

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2018 Une certain equivoque? A study of Vincent van Gogh's ambivalent engagement with prostitution, highlighted by the 1888 Courrier Francais controversy Saint-Davis, Fiona B. http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/12814 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. UNE CERTAIN ÉQUIVOQUE? A STUDY OF VINCENT VAN GOGH'S AMBIVALENT ENGAGEMENT WITH PROSTITUTION, HIGHLIGHTED BY THE 1888 COURRIER FRANÇAIS CENSORSHIP CONTROVERSY. by Fiona B. Saint-Davis A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of RESEARCH MASTERS School of Humanities and Performing Arts September 2018 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior consent. 2 Acknowledgements I am indebted to my tutors for their professional guidance and personal inspiration throughout this project. Professor Gemma Blackshaw, as my Director of Studies, has always been there for me with just the right word of advice and reassurance, often suggesting new avenues to explore, and encouraging me to own my research and situate it within current scholarship. -

Gods and Heroes: the Influence of the Classical World on Art in the 17Th & 18Th Centuries

23/04/2020 Cycladic Figure c 2500 BC Minoan Bull Leaper c 1500 BC Gods and Heroes: the Influence of the Classical World on Art in the 17th & 18th centuries Sophia Schliemann wearing “Helen’s Jewellery” Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk 1 2 Heracles from the Parthenon Paris and Helen krater c 700 BC Roman copy of Hellenistic bust of Homer Small bronze statue of Alexander the Great c 100 BC Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk 3 4 Judgement of Paris from Etruria c 550 BC Tiberius sword hilt showing Augustus as Jupiter Arrival of Aeneas in Italy Blacas Cameo showing Augustus with aegis breastplate Augustus of Prima Porta c 25 AD Dr William Sterling (discovered 1863) Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk 5 6 1 23/04/2020 Romulus and Remus on the Franks Casket c 700 AD Siege of Jerusalem from the Franks Casket Mantegna Triumph of Caesar Mantua c 1490 Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry c 1410 – tapestry of Trojan War Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk 7 8 The Colosseum Rome The Parthenon Athens The Pantheon Rome Artist’s Impression of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus showing surviving sculpture Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk 9 10 Hera and Zeus on the Parthenon Frieze in the British Museum Hermes, Dionysus, Demeter and Ares on the Parthenon Frieze Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling -

The French Venus

The French Venus “Les déesses nous ennuient déjà ; elles sont blafardes et maigres, ces pauvres déesses égarées dans notre siècle de science ; il n'y a plus que les vieillards qui s'aperçoivent de leur nudité.” Emile Zola, dans 'Causerie' La Tribune, le 30 août 1868 “Tu entends encore nos clameurs, Vénus immortelle! Après avoir aimé tes contemporains, tu es à nous, maintenant, à nous tous, à l'univers. Il semble que les vingt-cinq siècles de ta vie aient seulement consacré ton invincible jeunesse.” Auguste Rodin, dans 'A la Vénus de Milo' Paris, La Jeune Parque, 1945, p.2 First published in L'Art et les Artistes, n° 60, t. 10: 242-255, 1910. “A great private collection is a material concentrate that continually stimulates, that overexcites. Not only because it can always be added to, but because it is already too much. The collector's need is precisely for excess, for surfeit, for profusion. ........................................... A collection is always more than is necessary.” Susan Sontag in 'The Vulcano Lover – A Romance' London, Vintage, 1993, p.72 The Iconography of Venus from the Middle Ages to Modern Times Volume 2.1 The French Venus A topical catalogue of sculptures, reliefs, paintings, frescos, drawings, prints and illustrations of identified French artists Compiled by K. Bender 2009 To C and all my friends who are supporting me Cover illustration: ‘Vénus de Milo’, 2001 by ARMAN. Sculpture in iron, 52x15x20 cm. Private collection (serial number 28 in edition of 80). Photo AVdV. Authorization for reproduction requested. A hard copy and a digital pdf version are available at www.lulu.com Copyright 2009 by K. -

Texts to the Illustrations

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Antiquity in plaster : production, reception and destruction of plaster copies from the Athenian Agora to Felix Meritis in Amsterdam Godin, F.T.J. Publication date 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Godin, F. T. J. (2009). Antiquity in plaster : production, reception and destruction of plaster copies from the Athenian Agora to Felix Meritis in Amsterdam. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 Venus or Diana (ancient Roman statue in Treves) ill.3-6 Victory: statue at the temple in Henna 38 Victory statue: controversy over the statue at the Curia in Rome 43 Vier Bücher von menschlicher Proportion -

The Biography of Cultures: Style, Objects and Agency Proposal for an Interdisciplinary Approach

Les Cahiers de l’École du Louvre Recherches en histoire de l’art, histoire des civilisations, archéologie, anthropologie et muséologie 7 | 2015 Cahiers 7 The biography of cultures: style, objects and agency Proposal for an interdisciplinary approach Caroline van Eck, Miguel John Versluys and Pieter ter Keurs Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cel/275 DOI: 10.4000/cel.275 ISSN: 2262-208X Publisher École du Louvre Electronic reference Caroline van Eck, Miguel John Versluys and Pieter ter Keurs, « The biography of cultures: style, objects and agency », Les Cahiers de l’École du Louvre [Online], 7 | 2015, Online since 01 October 2015, connection on 15 February 2018. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cel/275 ; DOI : 10.4000/ cel.275 Les Cahiers de l'École du Louvre sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Cahiers de l’École du Louvre recherches en histoire de l’art, histoire des civilisations archéologie, anthropologie et muséologie Numéro 7. Octobre 2015 The biography of cultures: style, objects and agency. Proposal for an interdisciplinary approach. Caroline van Eck, Miguel John Versluys, Pieter ter Keurs Article disponible en ligne à l’adresse : http://www.ecoledulouvre.fr/cahiers-de-l-ecole-du-louvre/numero7octobre-2015/vaneck.pdf Pour citer cet article : Caroline van Eck, Miguel John Versluys, Pieter ter Keurs, « The biography of cultures: style, objects and agency. Proposal for an interdisciplinary approach. » [en ligne] no 7, octobre 2015, p. 2 à 22. © École du Louvre Cet article est mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution – Pas d’utilisation commerciale – Pas de modiication 3.0 non transposé. -

MUSE, Volume 47, 2013

MVSE volume forty-seven 2013 ANNUAL OF THE MUseUM OF ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI MVSE VOLUME FORTY-SEVEN 2013 Annual of the Museum of Art and Archaeology University of Missouri 115 Business Loop 70 West, Mizzou North Columbia, MO 65211-8310 Telephone: (573) 882-3591 Web site: http://maa.missouri.edu Jane Biers Editor Cathy Callaway Jeffrey Wilcox Assistant Editors Cassidy Shearrer Graphic Design © 2015 by the Curators of the University of Missouri ISSN 0077-2194 ISBN 0-910501-45-9 The Museum of Art and Archaeology is open from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Tuesday through Friday and from noon to 4:00 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. Admission is free. The museum is closed on Mondays, from December 25 through January 1, and on University of Missouri holidays: Martin Luther King Day, Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving Day, and the Friday following. Guided tours are available, if scheduled two weeks in advance. The Museum Store is open from 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Tuesday through Friday and from noon to 4:00 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. Back numbers of Muse are available from the Museum of Art and Archaeology. All submitted manuscripts are reviewed. Front cover: Keith Crown (American, 1918–2010) The Gravel Pit near Taos, New Mexico, 1992 Watercolor, 76.5 x 57 cm (sheet) Gift fo Patricia Dahlman Crown (2013.14) Back cover: Nam June Paik (Korean, 1932–2006) Anten-nalope, 1996 Mixed media, H. 2.68 m (with antenna) Gilbreath-McLorn Museum Fund (2000.2) T able of Contents Nn Director’s Report 2013 Alex W.