Old Sights with New Eyes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year of Le Nôtre

ch VER ât Sail ecouverture conférence de presse version déf.indd 1 aules 18/01/2012 13:01:48 3 CONTENTS Press conference - 26 january 2012 Foreword 4 Versailles on the move 7 The exhibitions in versailles 8 Versailles to arras 12 Events 13 Shows 15 Versailles rediscovered 19 Refurnishing versailles 21 What the rooms were used for 26 Versailles and its research centre 28 Versailles for all 31 2011, Better knowledge of the visitors to versailles 32 A better welcome, more information 34 Winning the loyalty of visitors 40 Versailles under construction 42 The development plan 43 Safeguarding and developing our heritage 48 More on versailles 60 Budget 61 Developing and enhancing the brand 63 Sponsors of versailles 64 Versailles in figures 65 Appendices 67 Background of the palace of versailles 68 Versailles in brief 70 Sponsors of the palace of versailles 72 List of the acquisitions 74 Advice for visitors 78 Contacts 80 4 Foreword This is the first time since I was appointed the effects of the work programme of the first phase President of the Public Establishment of the Palace, of the “Grand Versailles” development plan will be Museum and National Estate of Versailles that I considerable. But the creation of this gallery which have had the pleasure of meeting the press. will present the transformations of the estate since Flanked by the team that marks the continuity Louis XIII built his hunting lodge here marks our and the solidity of this institution, I will review the determination to provide better reception facilities remarkable results of 2011 and, above all, the major for our constantly growing numbers of visitors by projects of the year ahead of us. -

Campus Security's New Eyes Volunteer Radio Station WNMC Has Been Taken Over by the College and Effectively Censored

January 28, 2008 Vol. XXIV No. 7 one copy FREE NORTHWESTERN MICHIGAN COLLEGE WHITE PINE P *A2 We hew to the line; let the chips fall where they may Granny Flats a No-Go TWISTING REALITY Last month the Traverse City Commission voted 5-2 against an ordinance that would have allowed Accessory Dwelling Units, affectionately called Granny Flats, in Traverse City. The ordinance was originally presented to attract young professionals to the city by FIRST-YEAR NMC providing affordable housing. STUDENT Sarah Za Twenty-one TC residents spoke tolokin makes faces on the issue at the December 10 in the distorted mirror Commission meeting. Mayor simulator at the Den- Estes told the White Pine Press, nos Museum. Actually a “I think the city would like camera that warps your two things: we would like to image straight from the see young people stay and we lens to a screen, the would like to see more people simulator is one of the here. But when the commission many unique and inter had the chance to weigh that, esting features at the they didn’t see how ADUs museum. "No matter would solve that issue.” what's going on at Den- nos, you have to check NMCs Wikipedia out this playroom," said Hiccup Zatolokin. "It's my new From Dec. 15 through favorite thing to do." Jan. 3, two negative and Press photo/KAYLEIGH MARLIN accusatory paragraphs were posted on NMCs Wikipedia site. Wikipedia user “Politicaldiscrimination” claimed in paragraph one that the Campus security's new eyes volunteer radio station WNMC has been taken over by the college and effectively censored. -

Gods and Heroes: the Influence of the Classical World on Art in the 17Th & 18Th Centuries

12/09/2017 Cycladic Figure c 2500 BC Minoan Bull Leaper c 1500 BC Gods and Heroes: the Influence of the Classical World on Art in the 17th & 18th centuries Sophia Schliemann wearing “Helen’s Jewellery” Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk Heracles from the Parthenon Paris and Helen krater c 700 BC Roman copy of Hellenistic bust of Homer Small bronze statue of Alexander the Great c 100 BC Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk Judgement of Paris from Etruria c 550 BC Tiberius sword hilt showing Augustus as Jupiter Arrival of Aeneas in Italy Blacas Cameo showing Augustus with aegis breastplate Augustus of Prima Porta c 25 AD Dr William Sterling (discovered 1863) Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk 1 12/09/2017 Romulus and Remus on the Franks Casket c 700 AD Siege of Jerusalem from the Franks Casket Mantegna Triumph of Caesar Mantua c 1490 Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry c 1410 – tapestry of Trojan War Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk The Colosseum Rome The Parthenon Athens The Pantheon Rome Artist’s Impression of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus showing surviving sculpture Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk Hera and Zeus on the Parthenon Frieze in the British Museum Hermes, Dionysus, Demeter and Ares on the Parthenon Frieze Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk -

Vezzosi A. Sabato A. the New Genealogical Tree of the Da Vinci

HUMAN EVOLUTION Vol. 36 - n. 1-2 (1-90) - 2021 Vezzosi A. The New Genealogical Tree of the Da Vinci Leonardo scholar, art historian Family for Leonardo’s DNA. Founder of Museo Ideale Leonardo Da Vinci Ancestors and descendants in direct male Via IV Novembre 2 line down to the present XXI generation* 50059 Vinci (FI), Italy This research demonstrates in a documented manner the con- E-mail: [email protected] tinuity in the direct male line, from father to son, of the Da Vinci family starting with Michele (XIV century) to fourteen Sabato A. living descendants through twenty-one generations and four Historian, writer different branches, which from the XV generation (Tommaso), President of Associazione in turn generate other line branches. Such results are eagerly Leonardo Da Vinci Heritage awaited from an historical viewpoint, with the correction of the E-mail: leonardodavinciheritage@ previous Da Vinci trees (especially Uzielli, 1872, and Smiraglia gmail.com Scognamiglio, 1900) which reached down to and hinted at the XVI generation (with several errors and omissions), and an up- DOI: 10.14673/HE2021121077 date on the living. Like the surname, male heredity connects the history of regis- try records with biological history along separate lineages. Be- KEY WORDS: Leonardo Da Vinci, cause of this, the present genealogy, which spans almost seven Da Vinci new genealogy, ancestors, hundred years, can be used to verify, by means of the most living descendants, XXI generations, innovative technologies of molecular biology, the unbroken Domenico di ser Piero, Y chromosome, transmission of the Y chromosome (through the living descend- Florence, Bottinaccio (Montespertoli), ants and ancient tombs, even if with some small variations due burials, Da Vinci family tomb in Vinci, to time) with a view to confirming the recovery of Leonardo’s Santa Croce church in Vinci, Ground Y marker. -

The Ideal of Lucretia in Augustan Latin Poetry

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-05-07 The Ideal of Lucretia in Augustan Latin Poetry Waters, Alison Waters, A. (2013). The Ideal of Lucretia in Augustan Latin Poetry (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28172 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/705 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Ideal of Lucretia in Augustan Latin Poetry by Alison Ferguson Waters A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF GREEK AND ROMAN STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA MAY 2013 © Alison Ferguson Waters 2013 ii Abstract This study concerns the figure of Lucretia as she is presented by the Roman historian Livy in the first book of Ab Urbe Condita, where she is intended as an example of virtue, particularly in terms of her attention to woolworking. To find evidence for this ideal and how it was regarded at the time, in this study a survey is made of woolworking references in the contemporary Augustan poets Vergil, Tibullus, Propertius and Ovid. Other extant versions of the Lucretia legend do not mention woolworking; Livy appears to have added Lucretia’s devotion to wool, a tradition in keeping with Augustan propaganda. -

Heim Gallery Records, 1965-1991

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5779r8sb No online items Finding aid for the Heim Gallery records, 1965-1991 Finding aid prepared by Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Heim Gallery 910004 1 records, 1965-1991 Descriptive Summary Title: Heim Gallery records Date (inclusive): 1965-1991 Number: 910004 Creator/Collector: Heim Gallery Physical Description: 120.0 linear feet(271 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: London gallery directed by Andrew Ciechanowieck. Records include extensive correspondence with museums, galleries, collectors, and other colleagues in Europe and the United States. Photographs document paintings, drawings, sculptures, and decorative art sold and exhibited by, and offered to the gallery. Stock and financial records trace acquisitions and sales. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note Heim Gallery London began in June 1966 with François Heim (from Galerie Heim, Paris, begun 1954) and Andrew S. Ciechanowiecki as partners. Ciechanowiecki served as director in London while Heim remained in France. The emphasis of the gallery was Old Master paintings, especially French of the 15th - 18th century, Italian paintings of all periods, and sculpture (marble, terracotta and bronze) from the Renaissance to the 19th century. The gallery was known for its scholarly exhibitions and catalogs. Between 1966 and 1989 the gallery presented exhibitions two to three times a year. The gallery did business with museums and individual clients in Europe and the United States. -

A Social and Cultural History of the New Zealand Horse

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. A SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE NEW ZEALAND HORSE CAROLYN JEAN MINCHAM 2008 E.J. Brock, ‘Traducer’ from New Zealand Country Journal.4:1 (1880). A Social and Cultural History of the New Zealand Horse A Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Massey University, Albany, New Zealand Carolyn Jean Mincham 2008 i Abstract Both in the present and the past, horses have a strong presence in New Zealand society and culture. The country’s temperate climate and colonial environment allowed horses to flourish and accordingly became accessible to a wide range of people. Horses acted as an agent of colonisation for their role in shaping the landscape and fostering relationships between coloniser and colonised. Imported horses and the traditions associated with them, served to maintain a cultural link between Great Britain and her colony, a characteristic that continued well into the twentieth century. Not all of these transplanted readily to the colonial frontier and so they were modified to suit the land and its people. There are a number of horses that have meaning to this country. The journey horse, sport horse, work horse, warhorse, wild horse, pony and Māori horse have all contributed to the creation of ideas about community and nationhood. How these horses are represented in history, literature and imagery reveal much of the attitudes, values, aspirations and anxieties of the times. -

A Story of Five Amazons Brunilde S

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology Faculty Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology Research and Scholarship 1974 A Story of Five Amazons Brunilde S. Ridgway Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation Ridgway, Brunilde S. 1974. A Story of Five Amazons. American Journal of Archaeology 78:1-17. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/arch_pubs/79 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Story of Five Amazons* BRUNILDE SISMONDO RIDGWAY PLATES 1-4 THEANCIENT SOURCE dam a sua quisqueiudicassent. Haec est Polycliti, In a well-knownpassage of his book on bronze proximaab ea Phidiae, tertia Cresilae,quarta Cy- sculpturePliny tells us the story of a competition donis, quinta Phradmonis." among five artists for the statue of an Amazon This texthas been variously interpreted, emended, (Pliny NH 34.53): "Venereautem et in certamen and supplementedby trying to identifyeach statue laudatissimi,quamquam diversis aetatibusgeniti, mentionedby Pliny among the typesextant in our quoniamfecerunt Amazonas, quae cum in templo museums. It may thereforebe useful to review Dianae Ephesiaedicarentur, placuit eligi probatis- brieflythe basicpoints made by the passage,before simam ipsorum artificum, qui praesenteserant examining the sculpturalcandidates. iudicio,cum apparuitearn esse quam omnes secun- i) The Competition.The mention of a contest * The following works will be quoted in abbreviated form: von Bothmer D. -

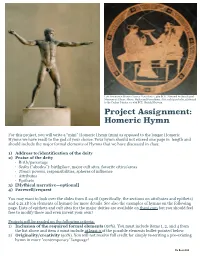

Myth Homeric Hymn Assignment

Left: Artemision Bronze (Zeus or Poseidon). c. 460 BCE. National Archaeological Museum of Athens. Above: Hades and Persephone. Attic red figure kylix, attributed to the Codrus Painter. ca. 430 BCE. British Museum Project Assignment: Homeric Hymn For this project, you will write a “mini” Homeric Hymn (mini as opposed to the longer Homeric Hymns we have read) to the god of your choice. Your hymn should not exceed one page in length and should include the major formal elements of Hymns that we have discussed in class: 1) Address to/identification of the deity 2) Praise of the deity • Birth/parentage • Sedes (“abodes”): birthplace, major cult sites, favorite cities/areas • Timai: powers, responsibilities, spheres of influence • Attributes • Epithets 3) [Mythical narrative—optional] 4) Farewell/request You may want to look over the slides from 8.24.18 (specifically, the sections on attributes and epithets) and 9.21.18 (on elements of hymns) for more details. See also the examples of hymns on the following page. Lists of epithets and cult sites for the major deities are available on theoi.com but you should feel free to modify these and even invent your own! Projects will be graded on the following criteria: 1) Inclusion of the required formal elements (50%). You must include items 1, 2, and 4 from the list above and item 2 must include at least 3 of the possible elements bullet-pointed below. 2) Originality/creativity (50%). You will not receive full credit for simply re-writing a pre-existing hymn in more “contemporary” language! Below are some examples of “real” Homeric Hymns. -

Three New Fabrication Inventions from Stone Pro and Braxton-Bragg, After a Great Deal of Hard Work, Several It- Even in a Tree Stand

www.slipperyrockgazette.net VOLUME 22, ISSUE 260 THE BEACON OF THE STONE INDUSTRY FEBRUARY 2016 My New Year’s Cleaning ike a shiny new penny, Jodi Wallace the upcoming year offers Owner, Monarch Solid us the opportunity to look L Surface Designs through new eyes with optimism and excitement for adventures of April) are always my biggest yet to come. Having survived stress months, since jobs are usu- the holiday madness, we now ally slow in coming. I make a lot have the chance to reflect on the of follow-up calls to customers, previous year with less stress trying to get them to commit to a and less emotional attachment. signed contract, and gently nudge It’s a chance to review and give to get things actually scheduled thought to what worked and what and started. Nothing feels worse didn’t, evaluate ideas you may to me than having to call my guys have had simmering on the back and telling them not to come in Stone Pro and Braxton-Bragg have a proven history of burner, or brainstorm new oppor- because there is no work in the introducing tools and products that solve a fundamen- tunities for the coming year. shop. tal problem facing fabricators and installers. We review But I also view some of this these three new products that raise the bar for efficiency. There’s usually work for our quiet time as an opportunity for shop in January, whether it‘s a “new year’s cleaning” (my ver- finishing up jobs that started in sion of a spring cleaning, except December, or jobs that I have it’s for my business). -

"New Eyes", Il Sorprendente Album Dei Clean Bandit

VENERDì 30 MAGGIO 2014 Che RATHER BE sia la traccia del 2014 ci sono pochi dubbi: record mondiale di streaming su Spotify (oltre 108 milioni), la traccia più "shazammata" di sempre in tutto il mondo, record di vendite in UK e nel "New Eyes", il sorprendente album resto del mondo (in Italia già platino e stabile ai vertici dell'airplay dei Clean Bandit radiofonico). Il relativo video ha oltre 56 milioni di visualizzazioni E, come se non bastasse, la loro prima settimana in classifica, con 163.000 copie "Extraordinary", il nuovo singolo esordisce ai vendute, ha segnato un altro record: quello del singolo più venduto nella vertici della classifica UK prima settimana di Gennaio dal 1996. Arriva ora NEW EYES il sorprendente album dei CLEAN BANDIT, in uscita il 3 giugno. Il secondo singolo EXTRAORDINARY esordisce ai vertici della LA REDAZIONE classifica UK e le premesse sono quelle di un altro grande successo. Questi sono solo i primi numeri di album che è destinato a diventare la colonna sonora dell'estate. Il loro "NEW EYES" porterà di nuovo il quartetto composto dai fratelli Jack e Luke Patterson insieme ai compagni di Università Grace Chatto e Nel Amin-Smith, ancora sotto i [email protected] riflettori di tutto il mondo. SPETTACOLINEWS.IT L'album trae la sua ispirazione da influenze UK dance / Soul /elettronici un sound di rottura: Massive Attack, Basement Jaxx e Soul II Soul. 'Extraordinary' è un brano capace di generare emozioni facendo vibrare le corde del cuore, batteria in acciaio accompagnata dalla voce piena di sentimento di Sharna Bass un brano che ci porta all'estate con forza e vigore. -

Insights from Stourhead Gardens

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Myth In Reception: Insights From Stourhead Gardens Thesis How to cite: Harrison, John Edward (2018). Myth In Reception: Insights From Stourhead Gardens. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2017 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000d97e Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Myth in reception: Insights from Stourhead gardens John Edward Harrison BSc (Hons) Psychology, University of Hertfordshire, UK Dip CS, Open University, UK PhD Neuroscience, University of London, UK Thesis submitted to The Open University in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS) The Open University December 2017 1 Declaration I declare that this thesis represents my own work, except where due acknowledgement is made, and that is has not been previously submitted to the Open University or to any other institution for a degree, diploma or other qualification. 2 Abstract The focus of my thesis is the reception of classical myth in Georgian Britain as exemplified by responses to the garden imagery at Stourhead, Wiltshire. Previous explanations have tended to the view that the gardens were designed to recapitulate Virgil’s Aeneid.