The Motya Charioteer in the Feminine Mode Hilah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year of Le Nôtre

ch VER ât Sail ecouverture conférence de presse version déf.indd 1 aules 18/01/2012 13:01:48 3 CONTENTS Press conference - 26 january 2012 Foreword 4 Versailles on the move 7 The exhibitions in versailles 8 Versailles to arras 12 Events 13 Shows 15 Versailles rediscovered 19 Refurnishing versailles 21 What the rooms were used for 26 Versailles and its research centre 28 Versailles for all 31 2011, Better knowledge of the visitors to versailles 32 A better welcome, more information 34 Winning the loyalty of visitors 40 Versailles under construction 42 The development plan 43 Safeguarding and developing our heritage 48 More on versailles 60 Budget 61 Developing and enhancing the brand 63 Sponsors of versailles 64 Versailles in figures 65 Appendices 67 Background of the palace of versailles 68 Versailles in brief 70 Sponsors of the palace of versailles 72 List of the acquisitions 74 Advice for visitors 78 Contacts 80 4 Foreword This is the first time since I was appointed the effects of the work programme of the first phase President of the Public Establishment of the Palace, of the “Grand Versailles” development plan will be Museum and National Estate of Versailles that I considerable. But the creation of this gallery which have had the pleasure of meeting the press. will present the transformations of the estate since Flanked by the team that marks the continuity Louis XIII built his hunting lodge here marks our and the solidity of this institution, I will review the determination to provide better reception facilities remarkable results of 2011 and, above all, the major for our constantly growing numbers of visitors by projects of the year ahead of us. -

Gods and Heroes: the Influence of the Classical World on Art in the 17Th & 18Th Centuries

12/09/2017 Cycladic Figure c 2500 BC Minoan Bull Leaper c 1500 BC Gods and Heroes: the Influence of the Classical World on Art in the 17th & 18th centuries Sophia Schliemann wearing “Helen’s Jewellery” Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk Heracles from the Parthenon Paris and Helen krater c 700 BC Roman copy of Hellenistic bust of Homer Small bronze statue of Alexander the Great c 100 BC Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk Judgement of Paris from Etruria c 550 BC Tiberius sword hilt showing Augustus as Jupiter Arrival of Aeneas in Italy Blacas Cameo showing Augustus with aegis breastplate Augustus of Prima Porta c 25 AD Dr William Sterling (discovered 1863) Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk 1 12/09/2017 Romulus and Remus on the Franks Casket c 700 AD Siege of Jerusalem from the Franks Casket Mantegna Triumph of Caesar Mantua c 1490 Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry c 1410 – tapestry of Trojan War Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk The Colosseum Rome The Parthenon Athens The Pantheon Rome Artist’s Impression of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus showing surviving sculpture Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk www.williamsterling.co.uk Hera and Zeus on the Parthenon Frieze in the British Museum Hermes, Dionysus, Demeter and Ares on the Parthenon Frieze Dr William Sterling Dr William Sterling www.williamsterling.co.uk -

Sicily's Ancient Landscapes & Timeless Traditions 2021

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® Sicily’s Ancient Landscapes & Timeless Traditions 2021 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. Sicily’s Ancient Landscapes & Timeless Traditions itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: Who doesn’t love to eat in Italy? But Sicilian food, which is heavily influenced by the Arabs who thrived here, is in a league of its own. Sample the local flavors when you visit the Tunisian-inflected town of Mazara del Vallo and share a traditional Sicilian lunch with a local family. As you savor the home-cooked fare, you’ll learn how the city’s identity continues to evolve, and the vital role of the local fishing industry. You’ll also visit a home of a very different sort, one that traveler Carol Bowman described as “a house full of hope.” It’s Casa di Maria, an organization (and Grand Circle Foundation partner) established by a family in Catania to provide a loving home for children who are refugees or victims of neglect and domestic violence. The daughter-in-law of the founders (Sergio and Carmela) will enlighten you about Sicily’s foster care system. And you’ll meet more of the Casa’s extended family, including a young Nigerian woman who literally showed up on Sicily’s shores with nothing and grew up here, and hear her harrowing—but ultimately inspiring—story. -

Download) 5 C A3 London, BM M

REGINA HANSLMAYR DIE SKULPTUREN VON EPHESOS • DIE HERMEN Hermen-Home.indd 1 16.10.16 20:01 FORSCHUNGEN IN EPHESOS Herausgegeben vom ÖSTERREICHISCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUT der ÖSTERREICHISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN IN WIEN BAND X/2 Hermen-Home.indd 2 16.10.16 20:01 REGINA HANSLMAYR Die Skulpturen von Ephesos Die Hermen MIT BEITRÄGEN VON GEORG A. PLATTNER, URSULA QUATEMBER Hermen-Home.indd 3 16.10.16 20:01 Vorgelegt von w. M. JOHANNES KODER in der Sitzung vom 28. April 2015 Umschlagabbildung: Schulterhermen aus Ephesos. Wien, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Antikensammlung Inv. I 848 und I 920. Fotos: Niki Gail, © ÖAW/ÖAI Umschlaggestaltung: Büro Pani; A. Sulzgruber Gestaltung der Tafeln: Regina Hanslmayr, Niki Gail Diese Publikation wurde einem anonymen, internationalen Peer-Review-Verfahren unterzogen. This publication has undergone the process of anonymous, international peer review. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie, detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.ddb.de> abrufbar. Die verwendete Papiersorte ist aus chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff hergestellt, frei von säurebildenden Bestandteilen und alterungsbeständig. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. ISBN 978-3-7001-7630-5 Copyright © 2016 by Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien Redaktion und Lektorat: Barbara Beck-Brandt Satz: Andrea Sulzgruber Druck: Prime Rate Kft., Budapest http://epub.oeaw.ac.at/7630-5 http://verlag.oeaw.ac.at Hermen-Home.indd -

The Medici Aphrodite Angel D

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite Angel D. Arvello Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Arvello, Angel D., "A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2015. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HELLENISTIC MASTERPIECE: THE MEDICI APRHODITE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Angel D. Arvello B. A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 1996 May 2005 In Memory of Marcel “Butch” Romagosa, Jr. (10 December 1948 - 31 August 1998) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the support of my parents, Paul and Daisy Arvello, the love and support of my husband, Kevin Hunter, and the guidance and inspiration of Professor Patricia Lawrence in addition to access to numerous photographs of hers and her coin collection. I would also like to thank Doug Smith both for his extensive website which was invaluable in writing chapter four and for his permission to reproduce the coin in his private collection. -

Cult Statue of a Goddess

On July 31, 2007, the Italian Ministry of Culture and the Getty Trust reached an agreement to return forty objects from the Museum’s antiq uities collection to Italy. Among these is the Cult Statue of a Goddess. This agreement was formally signed in Rome on September 25, 2007. Under the terms of the agreement, the statue will remain on view at the Getty Villa until the end of 2010. Cult Statue of a Goddess Summary of Proceedings from a Workshop Held at The Getty Villa May 9, 2007 i © 2007 The J. Paul Getty Trust Published on www.getty.edu in 2007 by The J. Paul Getty Museum Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 900491682 www.getty.edu Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief Benedicte Gilman, Editor Diane Franco, Typography ISBN 9780892369287 This publication may be downloaded and printed in its entirety. It may be reproduced, and copies distributed, for noncommercial, educational purposes only. Please properly attribute the material to its respective authors. For any other uses, please refer to the J. Paul Getty Trust’s Terms of Use. ii Cult Statue of a Goddess Summary of Proceedings from a Workshop Held at the Getty Villa, May 9, 2007 Schedule of Proceedings iii Introduction, Michael Brand 1 Acrolithic and Pseudoacrolithic Sculpture in Archaic and Classical Greece and the Provenance of the Getty Goddess Clemente Marconi 4 Observations on the Cult Statue Malcolm Bell, III 14 Petrographic and Micropalaeontological Data in Support of a Sicilian Origin for the Statue of Aphrodite Rosario Alaimo, Renato Giarrusso, Giuseppe Montana, and Patrick Quinn 23 Soil Residues Survey for the Getty Acrolithic Cult Statue of a Goddess John Twilley 29 Preliminary Pollen Analysis of a Soil Associated with the Cult Statue of a Goddess Pamela I. -

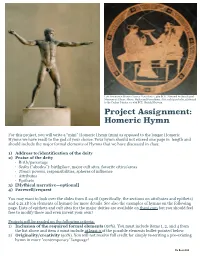

Myth Homeric Hymn Assignment

Left: Artemision Bronze (Zeus or Poseidon). c. 460 BCE. National Archaeological Museum of Athens. Above: Hades and Persephone. Attic red figure kylix, attributed to the Codrus Painter. ca. 430 BCE. British Museum Project Assignment: Homeric Hymn For this project, you will write a “mini” Homeric Hymn (mini as opposed to the longer Homeric Hymns we have read) to the god of your choice. Your hymn should not exceed one page in length and should include the major formal elements of Hymns that we have discussed in class: 1) Address to/identification of the deity 2) Praise of the deity • Birth/parentage • Sedes (“abodes”): birthplace, major cult sites, favorite cities/areas • Timai: powers, responsibilities, spheres of influence • Attributes • Epithets 3) [Mythical narrative—optional] 4) Farewell/request You may want to look over the slides from 8.24.18 (specifically, the sections on attributes and epithets) and 9.21.18 (on elements of hymns) for more details. See also the examples of hymns on the following page. Lists of epithets and cult sites for the major deities are available on theoi.com but you should feel free to modify these and even invent your own! Projects will be graded on the following criteria: 1) Inclusion of the required formal elements (50%). You must include items 1, 2, and 4 from the list above and item 2 must include at least 3 of the possible elements bullet-pointed below. 2) Originality/creativity (50%). You will not receive full credit for simply re-writing a pre-existing hymn in more “contemporary” language! Below are some examples of “real” Homeric Hymns. -

Greek Bronze Yearbook of the Irish Philosophical Society 2006 1

Expanded reprint Greek Bronze 1 In Memoriam: John J. Cleary (1949-2009) Greek Bronze: Holding a Mirror to Life Babette Babich Abstract: To explore the ethical and political role of life-sized bronzes in ancient Greece, as Pliny and others report between 3,000 and 73,000 such statues in a city like Rhodes, this article asks what these bronzes looked like. Using the resources of hermeneutic phenomenological reflection, as well as a review of the nature of bronze and casting techniques, it is argued that the ancient Greeks encountered such statues as images of themselves in agonistic tension in dynamic and political fashion. The Greek saw, and at the same time felt himself regarded by, the statue not as he believed the statue divine but because he was poised against the statue as a living exemplar. Socrates’ Ancestor Daedalus is known to most of us because of the story of Icarus but readers of Plato know him as a sculptor as Socrates claims him as ancestor, a genealogy consistently maintained in Plato’s dialogues.1 Not only is Socrates a stone-cutter himself but he was also known for his Daedalus-like ingenuity at loosening or unhinging his opponent’s arguments. When Euthyphro accuses him of shifting his opponents’ words (Meletus would soon make a similar charge), Socrates emphasizes this legacy to defend himself on traditionally pious grounds: if true, the accusation would set him above his legendary ancestor. Where Daedalus ‘only made his own inventions to move,’ Socrates—shades of the fabulous Baron von Münchhausen—would thus be supposed to have the power to ‘move those of other people as well’ (Euth. -

Catalogue of Paintings, Sculptures and Other Objects Exhibited During The

ART ' INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO CATALOGUE • OF PAINTINGS, ScuLPTURES AND OTHER OBJECTS EXHIBITED DURING THE WoRLD'S CoNGREssEs MAY 15 TO OCT. 31, 1893. THE ART INSTITUTE, Lake Front, opposite Adams Street, Chicago. THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO. CATALOGUE -OF- PAINTINGS, SCULPTURES AND OTHER OBJECTS EXHIBITED DURING THE WORLD'S CON- GRESSES. · SEPTEMBER, I893. CHICAGO, LAKE FRONT, HEAD OF ADAMS STREET. TRUSTEES OF THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, !892-J. CHARLES L. HUTCHINSON, SAMUEL M. NICKERSON, DAVID W. IRWIN, MARTIN A. RYERSON, EDWARD E. A YER, WILLIAM . T. BAKER, ELIPHALET W. BLATCHFORD, NATHANIEL K. FAIRBANK, JAMES H. DOLE, ALBERT A. SPRAGUE, JOHN C. BLACK, ADOI;PHUS C. BARTLETT, . JOHN J. GLESSNER, CHARLES D. HAMILL, EDSON KEITH, TURLINGTON W. HARVEY. ALLISON V. ARM01J.R, HOMER N. HIBBARD, MARSHALL FIELD, GEORGE N . CULVER, PHILANDER C. HANFORD. OFFICERS CHARLES L. HUTCHINSON, JAMES H. DOLE, President. V{ce-President. LYMAN J . GAGE, N.H. CARPENTER, Treasurer. Secretary. W . M. R. FRENCH, ALFRED EMERSON, Director. Curator of Classical Antiquities. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE <;HARLES L. HUTCHINSON, CHARLES D. HAMILL, JA)iES H. DOLE, JOHN C. BLACK, ALBERT A. SPRAGUE, MARTIN A. RYERSON, WILLIAM T . BAKER. THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO was incorporated May 24, 1879, for the purpose of maintaining a Museum and School of Art. The present building is built by the Art Institute and the World's Columbian Exposition jointly, at a cost of ~625,000, upon land granted by the city. At the end of the Fair the building will become the permanent and exclusive possession of· the Art Institute . During the Fair it is occupied by the World's Congresses. -

Invention of Hysteria : Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière / Georges Didi-Huberman ; Translated by Alisa Hartz

Invention of Hysteria This page intentionally left blank Invention of Hysteria Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière Georges Didi-Huberman Translated by Alisa Hartz The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Originally published in 1982 by Éditions Macula, Paris. ©1982 Éditions Macula, Paris. This translation ©2003 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or infor- mation storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Bembo by Graphic Composition, Inc. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Cet ouvrage, publié dans le cadre d’un programme d’aide à la publication, béné- ficie du soutien du Ministère des Affaires étrangères et du Service Culturel de l’Ambassade de France aux Etats-Unis. This work, published as part of a program of aid for publication, received sup- port from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in the United States. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Didi-Huberman, Georges. [Invention de l’hysterie, English] Invention of hysteria : Charcot and the photographic iconography of the Salpêtrière / Georges Didi-Huberman ; translated by Alisa Hartz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-04215-0 (hc. : alk. paper) 1. Salpêtrière (Hospital). 2. Hysteria—History. 3. Mental illness—Pictorial works. 4. Facial expression—History. -

Greek Sculpture Archaic Kore 660 BC to 590 BC • Archaic Period • All Female Youth Sculptures Were Called Kore

Greek Sculpture Archaic Kore 660 BC to 590 BC • Archaic Period • All female youth sculptures were called Kore. • Made of marble • Would have been painted with bright colors and decorated. • Archaic smile-corners of her mouth slightly lifted. • Hair is carved down the back showing Egyptian influence. • Would have been found in and around temples holding an offering in her outstretched hand. • The Kore were always clothed. • Not meant to house the soul or KA at death but may have been used as graver markers. • Represented the ideal female youth. • Flesh would have been painted lighter than the male kouros. Kouros 660 BC to 590 BC • 1st appearance coincides with trade with Egypt. • Usually a votive statue (representing a hero or athlete) or a grave marker. • Represented the god Apollo. • All male statues were called kouros and were nude. • Represented the ideal male youth. • Flesh would have been painted brown or red. classical The Discus Thrower by Myron • 480-440 BC • Roman copy of a Greek sculpture. • Shows an athlete in motion performing the Olympic event discus throwing. • Athletes performed nude • Romans copied all the Greek sculptures. Venus de Milo 150 BC • Classical Period • Sculpted by Alexandros of Antioch • Statue of Aphrodite (Venus) • Located at the Louvre museum in Paris • Found on the island of Milos in 1820 • Milos means “apple” in Greek • Would have been painted and adorned with jewelry • Made of marble • 6’8 feet tall • The arms were lost in transport. • Her face is neutral and drapery is realistic • Known for perfect graceful proportions Doryphorus (the spear bearer) 450 BC-415 BC • Polykleitos of Argos • Bronze • Known for his sculptures of young athletes • Known only through Roman copies • Perfect proportions • Idealized • Classical period • Contrapposto stance Hellenistic The Seated Boxer 225 BC • Votive statue- commemorated a known boxer. -

Art Hand-Book, Sculpture, Architecture, Painting

:. •'t-o^ * ^^' v^^ ^ ^^^^\ ^^.m <. .*^ .. X 0° 0^ \D^ *'ir.s^ A < V ^^; .HO^ 4 o *^,'^:^'*.^*'^ "<v*-^-%o-' 'V^^''\/^ V*^^'%^ V\^ o '^^ o'/vT^^^ll^"" vy:. -rb^ ^oVv^'' '^J^M^^r^^ ^^jl.^0'rSi' ^oK °<<. ^""^^ • Sculpture » Architecture * Painting Official H^NDBOOKo/ARCHITECTVRE and SCULPTURE and ART CATALOGUE TO THE Pan-American Exposition With Maps and Illustrations by -permission of C. D. Arnold, Official Photographer BUFFALO, NEW YORK, U. S. A., MAT FIRST TO NOVEMBER FIRST, M. CM. & I. Published by DAVID GRAY, Buffalo, N. Y. Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1901, by David Gray, in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. • • • • • e • • •• V. • » » « » . f>t • •_••» »'t»» » » » * • • . CONGRESS, Two Copiea Received JUN. 17 1901 Copyright entry EXPOSITION, 1901. CLASS ^XXc N». PAN-AMERICAN Buffalo, N. Y. , U. S. A COPY 3, Office of Director-General. March 30, 1901. To whom it may concern: — Mr. David Gray of this City has "been granted hy the Exposition a concession to publish the Art Catalogue of the Exposition^ which will he a hook in reality a memorial of the ideals of the Exposition in Archi- tecture, Sculpture and Pine Arts. WILLIAM I. BUCHANAN, Director-General The articles, pictures and catalogue descriptions in the Pan-American Art Hand Book are copyrighted, and publication thereof without permission is forbidden. \ r..k^ ^'««- -^ -"^^ ^^ This Art Hand Book was made by the publishing and printing house of ISAAC H,. BLANCHARD CO,, in the city of New Torky at 268 and 270 Canal Street, * 200 feet, iij9 inches east of Broadway.