Read It HERE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Max Neuhaus, R. Murray Schafer, and the Challenges of Noise

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2018 MAX NEUHAUS, R. MURRAY SCHAFER, AND THE CHALLENGES OF NOISE Megan Elizabeth Murph University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2018.233 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Murph, Megan Elizabeth, "MAX NEUHAUS, R. MURRAY SCHAFER, AND THE CHALLENGES OF NOISE" (2018). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 118. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/118 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

PROCEEDINGS of the THIRTY-FOURTH COMMENCEMENT of the RICE INSTITUTE, COURT of the CHEMISTRY LABORATORIES, JUNE 8 and 9, 1947 I PROGRAM a SUNDAY, JUNE 8, 6 P.M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Rice University PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-FOURTH COMMENCEMENT OF THE RICE INSTITUTE, COURT OF THE CHEMISTRY LABORATORIES, JUNE 8 AND 9, 1947 I PROGRAM a SUNDAY, JUNE 8, 6 P.M. Academic Procession. Veni Creator Spiritus. Invocation. 0 God, Our Help in Ages Past. Sermon . "The Summons to Responsible Existence," By the REV.DONALD HOUSTON STEWART, PR.D. (Edinburgh), Pastor of the Central Presbyterian Church of Houston Hundredth Psalm. Benediction. 6 MONDAY, JUNE 9, 8 :45 A.M. Academic Procession. Veni Creator Spiritus. Invocation. Address . "Education in Action," By FREDERICKHARD, PH.D., D.C.L., President of Scripps College Lord of All Being, Throned Afar. Conferring of Degrees in Course. N.R.O.T.C. Commissioning Ceremony. Announcements and Awards. America. Benediction. THE SUMMONS TO RESPONSIBLE EXISTENCE* Deuteronomy 30:rg; Philippians 2:12-13; Ephesians 3:zo; Jolzn Sr32- I have set before thee Iife and death . : therefore choose life . work out your own salvation with fear and trembling; for it is God which worketh in you both to will and to work . according to the power that worketh in us. and ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free. N these words the sobering significance and the arresting depths of life's inescapable disturbance break through. Whether he be ancient or modern, man is here confronted by that which is contemporary because it is perennial, and that which is perennial because it is ever contemporaneous. Life is always and everywhere an existence-in-decision, a summons to responsible existence. -

Canadianliterature / Littérature Canadienne

Canadian Literature / Littérature canadienne A Quarterly of Criticism and Review Number "#", Autumn "##$, Sport and the Athletic Body Published by !e University of British Columbia, Vancouver Editor: Margery Fee Associate Editors: Laura Moss (Reviews), Glenn Deer (Reviews), Larissa Lai (Poetry), Réjean Beaudoin (Francophone Writing), Judy Brown (Reviews) Past Editors: George Woodcock (%$&$–%$''), W.H. New (%$''–%$$&), Eva-Marie Kröller (%$$&–"##(), Laurie Ricou ("##(–"##') Editorial Board Heinz Antor Universität zu Köln Allison Calder University of Manitoba Kristina Fagan University of Saskatchewan Janice Fiamengo University of Ottawa Carole Gerson Simon Fraser University Helen Gilbert University of London Susan Gingell University of Saskatoon Faye Hammill University of Strathclyde Paul Hjartarson University of Alberta Coral Ann Howells University of Reading Smaro Kamboureli University of Guelph Jon Kertzer University of Calgary Ric Knowles University of Guelph Louise Ladouceur University of Alberta Patricia Merivale University of British Columbia Judit Molnár University of Debrecen Maureen Moynagh St. Francis Xavier University Reingard Nischik University of Constance Ian Rae King’s University College Roxanne Rimstead Université de Sherbrooke Sherry Simon Concordia University Patricia Smart Carleton University David Staines University of Ottawa Cynthia Sugars University of Ottawa Neil ten Kortenaar University of Toronto Marie Vautier University of Victoria Gillian Whitlock University of Queensland David Williams University of Manitoba -

Insert Client Name

CONFIDENTIAL, DRAFT, NOT FOR PUBLICATION OF ISSUE INTERNATIONAL UNION OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES (IUGS) INITIATIVE ON FORENSIC GEOLOGY (IFG) SUMMARY 2016 TO 2020 DRAFT Date Issued: 19 October 2020 Report Name: Summary 2016-2020 Report Status: Draft 2.0 International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS), Initiative on Forensic Geology (IFG) Summary 2016-2020 Author Dr Laurance Donnelly Chair Review by IFG Committee Prof Rob Fitzpatrick Vice Chair Prof Lorna Dawson, CBE Treasurer Ms Marianne Stam Secretary Commander Mark Harrison MBE Geoforensic Law Enforcement Adviser Ms Jodi Webb FBI Adviser Dr Alastair Ruffell Training and Publications Dr Elisa Bergslien Geoforensic International Network Dr Duncan Pirrie Special Publications Adviser Dr Ruth Morgan Forensic Science Adviser Dr Skip Palenik, Dr Christopher Palenik Geological (Trace) Evidence Advisers Prof Pier Matteo Barone Crime Scene Adviser Dr Brian Johnston, Dr Jennifer McKinley Website and Communications Dr Bill Schneck Officer, USA Prof Carlos Molina Gallego, Dr Fábio Augusto Da Silva Salvador Officers, Latin America Dr Rosa Maria Di Maggio Officer, Europe Dr Olga Gradusva, Dr Ekaterina Nesterina Officers, Russia and CIS Dr Ritsuko Sugita Officer, Japan Prof Shari Forbes Officer, Pacific Commander Mark Harrison MBE, Prof Rob Fitzpatrick Officer, Australia Prof Grant Wach Officer, Canada Dr Guo Hongling Officer, China Dr Biplob Chatterjee Officer, India Pending Officer, Africa Officers, Middle East Lieutenant Colonel Ahmed Saeed Al Kaabi, Captain Khudooma Said Al Naimi, Captain Saleh Ali Al Katheeri Donnelly, IUGS-IFG Summary, 2016-2020, 16.10.2020 Page 1 DRAFT INTERNATIONAL UNION OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES (IUGS) INITIATIVE ON FORENSIC GEOLOGY (IFG) SUMMARY, 2016 TO 2020 A. IFG COMMITTEE The following changes were made to the IUGS-IFG Committee: 1. -

United States Marine Corps Officer Selection Stations

CD Contents Introduction: ........................................................................................................................Page 02 Section 1: Why the Marine Corps? .....................................................................Page 14 Section 2: Programs .......................................................................................................Page 36 Section 3: Officer Training ...........................................................................................Page 44 Section 4: Areas of Specialization........................................................................Page 52 Section 4a: Aviation.........................................................................................................Page 56 Section 4b: Combat Arms.............................................................................................Page 96 Section 4c: Service Support......................................................................................Page 112 Section 4d: Law ..........................................................................................................Page 134 Section 5: Post-Graduate Educational Programs......................................Page 140 Section 6: Second Tour Opportunities...............................................................Page 154 Section 7: Life as a Marine Corps Officer.......................................................Page 164 Section 8: Who to contact..................................................................................Page -

2021-Spring.Pdf

The OFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the USF ALUMNI ASSOCIATION SPRING 2021 UNIVERSITY OF USFSOUTH FLORIDA MAGAZINE ALUMNUS IN THE LEAD Chris Sprowls ’06 Speaker of the Florida House IT'S ALL ABOUT WHO YOU KNOW USF Alumni could save more with a special discount with GEICO! geico.com/alum/usf | 1-800-368-2734 | Local Agent Some discounts, coverages,payment plans and features are not availablein all states, in all GEICO companies, or in all situations. Boat and PWC coveragesare underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. Motorcycle and ATV coverages are underwritten by GEICO Indemnity Company. Homeowners, renters and condo coveragesare written through non-affiliated insurance companies and are secured through the GEICO Insurance Agency. GEICO is a registeredservice mark 2 UNIVERSITY of SOUTH FLORIDA of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, D.C. 20076; a BerkshireHathaway Inc. subsidiary. GEICO Gecko® image© 1999-2020. © 2020 GEICO The OFFICIAL MAGAZINE of the USF ALUMNI ASSOCIATION IT'S ALL ABOUT SPRING 2021 WHO YOU KNOW USFUNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA MAGAZINE FEATURES USF Alumni could save 28-31 Mr. Speaker Photo: Florida House of Representatives more with a special Chris Sprowls, ‘06, leads Florida’s House of Representatives discount with GEICO! 32-35 Bulls in Tallahassee Meet five more USF graduates serving in the legislature 36-39 Relevant research Muma College of Business helps assess region’s 28 quality of life UNIVERSITY 4 From the president 5 Building an Equitable Future 6-9 First look 10-19 University 10 20-21 Athletics 22-27 Philanthropy 48-51 Outstanding Young Alumni 52-57 Salute to Life Members FOREVER BULLS 58-59 Where’s Rocky? 40 5 minutes with the Chair 60-63 Alumni roundup 41 Meet your 2020 64-67 Class notes USFAA Board 42 USFAA Annual Report GORDON CLARKE geico.com/alum/usf | 1-800-368-2734 | Local Agent COVER PHOTO: House Speaker Chris Sprowls during a 44-47 Sweet tradition: recent appearance on the USF. -

Winter 2004 11 Dispatches

DISPATCHES A Supreme Success Justice tells law students he had help getting to Wisconsin’s highest court. Anthony Davis JDx’05 was JEFF MILLER buoyed by the moment, a slice of history at the UW Law School where the road to fairness for aspiring minority lawyers just became a bit smoother. An African-American in his third year at the Law School, Davis joined about seventy other minority law students in August to welcome freshly sworn-in Wisconsin Supreme Court Jus- tice Louis Butler JD’77, the first African-American to serve on the state’s highest court. “The UW has one of the Justice Louis Butler, the first African-American to serve on the Wiscon- major law-school populations sin Supreme Court, recalls how high above the ground the judges sat of African-Americans,” Davis when he first appeared before the court. He hosted a luncheon with says. “To see that we finally minority students at his alma mater, the UW Law School, shortly after “We took what I would call have a supreme court judge being sworn in. gross liberties with history.” makes you think you can achieve some of the highest Butler, a Milwaukee County Education Opportunities pro- — Ben Karlin ’93, executive levels in the legal system. We’re circuit judge who was appointed gram (LEO), which is seen as a producer of The Daily Show, making strides. It’s a great time by Governor Jim Doyle ’67 to national model for recruiting, speaking at the Wisconsin Book to be in law school.” fill a supreme court vacancy, supporting, and retaining Festival in October about Amer- With minority students lauded those efforts in his first students from traditionally ica (The Book): A Citizen’s Guide making up about 25 percent of public appearance after his underrepresented communities. -

Plan and Specification Contract Jority of Committee N

JlmSm! .V.VVjf Hii SBS!?! ®tai tfSKS .fii&tei -'v - T Si THE PRESS ®Sk5^ An Institution Which Works 4 ^\ ' For Community Ack Polks; "Vi;i , * >n s% <„ f j!< <!' < vancement. - THE ONLY NEWSPAPER PUBLISHED IN CONN. The "Press" Covers More Than Twenty-Two Suburban Districts, Combining a Population of Over Thirty Thousand Between Hartford & Springfield it FORTY-FOURTH YEAR- NO. 52 THOMPSONVILLE, CONNECTICUT, THURSDAY, APRIL 24, 1924 PRICE $2.00 A YEAR—SINGLE COPY 5e|§§ 'ftS :> iir- LOCAL GIRL WEDS CHURCH MINSTREL !Pi Plan and Specification Contract m M ffp PITTSFIELD MAN AGAIN BIG SUCCESS ; mm * - * - Miss Nora Kennedy of ''Mi &W*$ Performances of St. An n jority of Committee Spring Street Is Bride drew's Church Players of Raymond Murray in Draw Capacity Crowds New Time Here This Action Taken At Meeting of the New High ; St. Patrick's Church. Both Evenings. School Building Committee Held Yesterday A pretty after Easter wedding The sixth annual minstrel perform EGINNING Monday morn ing, the Bigelow-Hartford Afternoon—Rumored Friction in the Commit Mrst Two Nights of Ten Night Bazaar and En took place Tuesday morning at 8 ance of the Men's Union and Girls' Friendly Society, of St. Andrew's BCarpet Co. will operate on tee Over the Financial Arrangements With the tertainment Draw Large Attendance—De- o'clock in St. Patrick's church when Episcopal Church was given Tuesday Daylight Saving Time. There will be no change of clocks in Architect and the Sum That the Specifications lightful Entertainments by Children of Mary,Miss Nora Kennedy, daughter of Mr. -

RAA Liaison Letter Spring 2014

Liaison Letter Front Cover Spring 2014-04.ai 1 14/10/2014 9:41:00 AM The Royal Australian Artillery LIAISON LETTER Spring 2014 85 th Anniversary ProofProof and Experimental Establishment – Port WakeWakefieldfield 1929-2014199929-20 14 The Official Journal of the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery Incorporating the Australian Gunner Magazine First Published in 1948 CONTENTS Editor’s Comment 4 Letters to the Editor 5 Regimental 10 Operations 22 Professional Papers 32 RAA Around the Regiment 50 Take Post 60 LIAISON Capability 64 Personnel & Training 68 LETTER Associations & Organisations 72 Spring Edition NEXT EDITION CONTRIBUTION DEADLINE Contributions for the Liaison Letter 2015 – Autumn 2014 Edition should be forwarded to the Editor by no later than Friday 27th February 2015. LIAISON LETTER ON-LINE Incorporating the The Liaison Letter is on the Regimental DRN web-site – Australian Gunner Magazine http://intranet.defence.gov.au/armyweb/Sites/RRAA/. Content managers are requested to add this to their links. Publication Information Front Cover: Proof & Experimental Establishment - Port Wakefield – 85th Anniversary Front Cover Theme by: Major D.T. (Terry) Brennan, Staff Officer to Head of Regiment Compiled and Edited by: Major D.T. (Terry) Brennan, Staff Officer to Head of Regiment Published by: Lieutenant Colonel Dave Edwards, Deputy Head of Regiment Desktop Publishing: Michelle Ray, Combined Arms Doctrine and Development Section, Puckapunyal, Victoria 3662 Front Cover & Graphic Design: Felicity Smith, Combined Arms Doctrine and Development Section, Puckapunyal, Victoria 3662 Printed by: Defence Publishing Service – Victoria Distribution: For issues relating to content or distribution contact the Editor on email: [email protected] or [email protected] Contributors are urged to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in their articles. -

![[New] Name? CENTER](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1229/new-name-center-6431229.webp)

[New] Name? CENTER

CENTER FOR HISTORY OF PHYSICS NEWSLETTER Vol. XXXIX, Number 1 Spring 2007 One Physics Ellipse, College Park, MD 20740-3843, Tel. 301-209-3165 Publication of the Collected Works of Niels Bohr Completed by Finn Aaserud ith the publication of the twelfth and final volume of the W Niels Bohr Collected Works, one of the very greatest physicists of the twentieth century is brought before the public in one of the premier works of scholarship in modern history of science. Planning for the publication of the Collected Works began soon after Bohr’s death in 1962. The driving force behind the project was Bohr’s close collaborator, the Belgian physicist and historian of science Léon Rosenfeld, who was the first General Editor of the series. The first volume, covering the early years up to 1911, was published in 1972 with Jens Rud Nielsen (1894–1979) as editor. However, this was the only volume that Rosenfeld would see, for he died in 1974. The project, originally conceived as a ten-year effort, was not completed until well into the next century. After an interim period with Rud Nielsen doing the brunt of the work, Erik Rüdinger was named General Editor in 1977. Mary Calvert using the 12-inch refractor at Yerkes Observatory, Rüdinger had served as Bohr’s scientific assistant for a brief February 23, 1926. She was Edward E. Barnard’s niece, and after period near the end of Bohr’s life. In Volume 5 (published his death, co-editor of his book A Photographic Atlas of Selected 1985), the first under Rüdinger’s control, Rüdinger laid out the Regions of the Milky Way published in 1927 by the Carnegie general editorial policy and practice that have been followed Institution of Washington. -

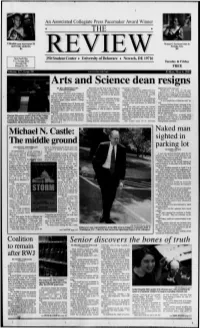

Arts and Science Dean Resigns by JILL LIEBOWITZ and Schiavelli Said the Dean of the College of Dilorenzo's Resignation

' An Associated Collegiate Press Pacemaker Award Winner •/ THE • UModels.com showcases 10 Women's lacrosse loses to university students, Temple, 8-6, . Bl B8 . Non-Profit Org. 250 Student Center • University of Delaware • Newark, DE 19716 U.S. Postage Paid Thesday & Friday Newark, DE Pennit No. 26 FREE \"oiUilll' 127. lssul' 50 www.re•·iew.udel.edu Friday~ l\la~ · 4~ 2001 Arts and Science dean resigns BY JILL LIEBOWITZ AND Schiavelli said the dean of the College of DiLorenzo's resignation. Huddleston into his new post. JONATHAN RIFKIN Arts and Science is the chief academic officer Huddleston said he was notified of his new Huddleston will draw on his past News Editors for the college, who ultimately makes faculty position by Schiavelli Wednesday evening, experiences serving as chairman for the Dean Thomas DiLorenzo of the.College of choice selections and controls the general and he said he had discussed the possible political science department and president of Arts and Science announced his·resignation administrative tasks. change with Schiavelli at aii earlier date. the Faculty Senate to fulfill the responsibilities Thursday after administrators decided the He said the position is important because DiLorenzo's resignation was announced that lie ahead. university's largest college needed a "change · its members constitute 55 percent of the via e-mail, which was sent to all faculty in the "A lot of people have wished me well," he in leadership." university population, or 8,500 students. College of Arts and Science by Schiavelli said. University President David P. Roselle said Schiavelli would not comment on yesterday. -

Marriages of Portsmouth Virginia 1931-1935

Marriages of Portsmouth Virginia 1931-1935 Date Husband Wife Ages Status Birthplaca Currently living @ Parents Husband Wife Husband Wife Husband Wife Occupation Official USS Idaho, Navy Edward Abraham John Lennox & ABRAHAM Edward LENNOX Jeanette San Francisco, Long Beach, Yard, Portsmouth, 827 Sixth St., & Mary Donders Mary Phillips J. W. 12-Feb-1932 Joseph Marie 21 22 S S CA CA VA Portsmouth, VA Abraham Lennox Machinist, USN Reynolds Juban John ACOSTA Francis Washington, 691 W. N Ave., 213 Elyton St., Acosta & Julia Clarke Yale & Chas. H. 21-Mar-1933 Joseph YORK Marie 52 40 W S Fernandine, FL DC New York, NY Birmingham, AL Ann Magee Agnes Adams Salesman Holmead John T. Light House James H. Acree Lawrence & ACREE Charlie LAWRENCE Ruth Portsmouth, Depot, 523 Lincoln St., & Josephine Mary F. 19-Aug-1935 Wilbert Eliece 32 21 D S Essex Co., VA VA Portsmouth, VA Portsmouth, VA Williams Thacker Pile Driver W. H. Corbitt USS Owl, Navy J. B. Dickerson DICKERSON Lawrence Yard, Portsmouth, 662 W. Second R. L. Adair & & Loraine Seaman 1st Chas. H. 6-Feb-1932 ADAIR Ira Clarence Thelma Marion 26 23 S S Cullman Co., AL Co., TN VA St., Memphis, TN Dora Echols Highland Class, USN Holmead 2808 Chestnut Edward C. ADAMS Edward MCLENORE Fayetteville, St., Portsmouth, Louis D. Adams McLemore & 23-Jan-1932 Earl Kathleen 21 21 S S Fayetteville, NC NC Fayetteville, NC VA & Maggie Butler Lena A. Beard Textile Worker Olin Ray Thaddeous ADAMS James MORGAN Marion Scotland 1123 Marion St., 1024 London St., ____ & Marion Morgan & Irene Elder C. A. 11-Aug-1931 Richard © Ernestine © 23 22 S S Norfolk, VA Neck, NC Norfolk, VA Portsmouth, VA Adams Marklin Laborer Twine John Edward Thomas A.