Public Participation in the Development of the Zenit Arena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Svjetsko Nogometno Prvenstvo I Njegov Ekonomski Utjecaj Na Zemlju Domaćina

Svjetsko nogometno prvenstvo i njegov ekonomski utjecaj na zemlju domaćina Purgar, Lucija Master's thesis / Specijalistički diplomski stručni 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Polytechnic of Međimurje in Čakovec / Međimursko veleučilište u Čakovcu Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:110:708564 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-01 Repository / Repozitorij: Polytechnic of Međimurje in Čakovec Repository - Polytechnic of Međimurje Undergraduate and Graduate Theses Repository MEĐIMURSKO VELEUČILIŠTE U ČAKOVCU SPECIJALISTIČKI DIPLOMSKI STRUČNI STUDIJ MENADŽMENT TURIZMA I SPORTA LUCIJA PURGAR SVJETSKO NOGOMETNO PRVENSTVO I NJEGOV EKONOMSKI UTJECAJ NA ZEMLJU DOMAĆINA ZAVRŠNI RAD ČAKOVEC, 2020. Lucija Purgar Svjetsko nogometno prvenstvo i njegov ekonomski utjecaj na zemlju domaćina ______________________________________________________________________ MEĐIMURSKO VELEUČILIŠTE U ČAKOVCU SPECIJALISTIČKI DIPLOMSKI STRUČNI STUDIJ MENADŽMENT TURIZMA I SPORTA LUCIJA PURGAR SVJETSKO NOGOMETNO PRVENSTVO I NJEGOV EKONOMSKI UTJECAJ NA ZEMLJU DOMAĆINA FIFA WORLD CUP AND ITS ECONOMIC IMPACT ON HOST COUNTRY ZAVRŠNI RAD Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Nevenka Breslauer, prof. v. š. ČAKOVEC, 2020. ____________________________________________________________________________ Međimursko veleučilište u Čakovcu 1 Lucija Purgar Svjetsko nogometno prvenstvo i njegov ekonomski utjecaj na zemlju domaćina ______________________________________________________________________ -

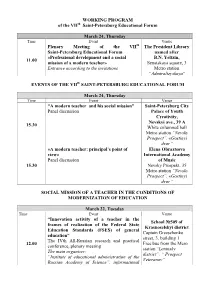

WORKING PROGRAM of the VII Saint-Petersburg Educational

WORKING PROGRAM of the VIIth Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue Plenary Meeting of the VIIth The President Library Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum named after «Professional development and a social B.N. Yeltzin, 11.00 mission of a modern teacher» Senatskaya square, 3 Entrance according to the invitations Metro station “Admiralteyskaya” EVENTS OF THE VIIth SAINT-PETERSBURG EDUCATIONAL FORUM March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue “A modern teacher and his social mission” Saint-Petersburg City Panel discussion Palace of Youth Creativity, Nevskyi ave., 39 A 15.30 White columned hall Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” «A modern teacher: principal’s point of Elena Obraztsova view» International Academy Panel discussion of Music 15.30 Nevsky Prospekt, 35 Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” SOCIAL MISSION OF A TEACHER IN THE CONDITIONS OF MODERNIZATION OF EDUCATION March 22, Tuesday Time Event Venue “Innovation activity of a teacher in the School №509 of frames of realization of the Federal State Krasnoselskyi district Education Standards (FSES) of general Captain Greeschenko education” street, 3, building 1 The IVth All-Russian research and practical 12.00 Free bus from the Mero conference, plenary meeting station “Leninsky The main organizer: district”, “ Prospect “Institute of educational administration of the Veteranov” Russian Academy of Science”, informational and methodological center of Krasnoselskyi district of Saint-Petersburg, School №509 of Krasnoselskyi district March -

2016 Veth Manuel 1142220 Et

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Selling the People's Game Football's transition from Communism to Capitalism in the Soviet Union and its Successor State Veth, Karl Manuel Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 Selling the People’s Game: Football's Transition from Communism to Capitalism in the Soviet Union and its Successor States K. -

Match Schedule for the World Cup 2018 Group Phase

Match schedule for the World Cup 2018 group phase Date Local Time Teams Location Russia vs Luzhniki Stadium, June 14, 2018 7:00 PM Saudi Arabia Moscow Central Stadium, June 15, 2018 4:00 PM Egypt vs Uruguay Yekaterinburg Fisht Olympic June 15, 2018 10:00 PM Portugal vs Spain Stadium, Sochi Krestovsky Stadium, June 15, 2018 7:00 PM Morocco vs Iran Saint Petersburg June 16, 2018 2:00 PM France vs Australia Kazan Arena, Kazan Mordovia Arena, June 16, 2018 8:00 PM Peru vs Denmark Saransk Otkrytiye Arena, June 16, 2018 5:00 PM Argentina vs Iceland Moscow Kaliningrad Stadium, June 16, 2018 11:00 PM Croatia vs Nigeria Kaliningrad Brazil vs Switzer- Rostov Arena, June 17, 2018 10:00 PM land Rostov-on-Don Costa Rica vs Ser- Cosmos Arena, June 17, 2018 4:00 PM bia Samara Luzhniki Stadium, June 17, 2018 7:00 PM Germany vs Mexico Moscow Nizhny Novgorod Sweden vs June 18, 2018 4:00 PM Stadium, South Korea Nizhny Novgorod Fisht Olympic June 18, 2018 7:00 PM Belgium vs Panama Stadium, Sochi Volgograd Arena, June 18, 2018 10:00 PM Tunisia vs England Volgograd Otkrytiye Arena, June 19, 2018 7:00 PM Poland vs Senegal Moscow Mordovia Arena, June 19, 2018 4:00 PM Colombia vs Japan Saransk Krestovsky Stadium, June 19, 2018 10:00 PM Russia vs Egypt Saint Petersburg Uruguay vs Rostov Arena, June 20, 2018 7:00 PM Saudi Arabia Rostov-on-Don Luzhniki Stadium, June 20, 2018 4:00 PM Portugal vs Morocco Moscow June 20, 2018 10:00 PM Iran vs Spain Kazan Arena, Kazan Central Stadium, June 21, 2018 7:00 PM France vs Peru Yekaterinburg Denmark vs Cosmos Arena, June 21, -

Croatia Vs England Full Game Torrent Download World Cup Full Matches

croatia vs england full game torrent download World Cup full matches. Footballia is the first free interactive football video library where you can watch full football matches for free anytime, anywhere. Thank you! First of all, we’d like to tell you how grateful we are to all of you who stuck by us during our offline period. Thank you so much! Keep Footballia alive! But the threat is not gone. As you know, in recent months, Footballia has been in danger of disappearing. We’ve improved our protection so you can keep enjoying football history, but as a consequence, our expenses have increased. How can you help? Many of you have asked how you can help the project. The best way is to subscribe to Footballia Master. Not only will you make the project stronger, but you’ll get a bunch of cool features in return! Randomizer. You don't know which match to watch today among more than 20,000 available on Footballia? Footballia Randomizer is a new tool that will take you to a random match of the Footballia catalogue. World Cup full matches. Footballia is the first free interactive football video library where you can watch full football matches for free anytime, anywhere. Thank you! First of all, we’d like to tell you how grateful we are to all of you who stuck by us during our offline period. Thank you so much! Keep Footballia alive! But the threat is not gone. As you know, in recent months, Footballia has been in danger of disappearing. -

Urban Planning

Leonid Lavrov, Elena Molotkova, Andrey Surovenkov — Pages 29–42 ON EVALUATING THE CONDITION OF THE SAINT PETERSBURG HISTORIC CENTER DOI: 10.23968/2500-0055-2020-5-3-29-42 Urban Planning ON EVALUATING THE CONDITION OF THE SAINT PETERSBURG HISTORIC CENTER Leonid Lavrov, Elena Molotkova*, Andrey Surovenkov Saint Petersburg State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering Vtoraja Krasnoarmeyskaya st., 4, Saint Petersburg, Russia *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Introduction: This study was prompted by the introduction of the urban environment quality index into the system operated by the Russian Ministry of Construction Industry, Housing and Utilities Sector (Minstroy). We note that the ˝environment-centric˝ methodologies were already worked on and applied to housing studies in Leningrad as far back as during the 1970–1980s, and that the insights from these studies can now be used for analyzing the current state of the urban environment. Purpose of the study and methods: The information reviewed in this article gives us the first glimpse of the tangible urban environment in the historic center of Saint Petersburg. Many features of this part of the city are reminiscent of other European metropolises, but the fact that the historic center is split into three parts by vast waterways, that the construction began from the ground up in the middle of the wilderness, and that the active urban development phase lasted only a century and a half (from the 1760s to the 1910s), has a major part to play. Results: We use quantitative data to describe the features of the Saint Petersburg historic center and compare our findings to the features of European metropolises, across such parameters as spatial geometry, transportation and pedestrian links, and environmental conditions. -

Women's Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011

Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 A Project Funded by the UEFA Research Grant Programme Jean Williams Senior Research Fellow International Centre for Sports History and Culture De Montfort University Contents: Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971- 2011 Contents Page i Abbreviations and Acronyms iii Introduction: Women’s Football and Europe 1 1.1 Post-war Europes 1 1.2 UEFA & European competitions 11 1.3 Conclusion 25 References 27 Chapter Two: Sources and Methods 36 2.1 Perceptions of a Global Game 36 2.2 Methods and Sources 43 References 47 Chapter Three: Micro, Meso, Macro Professionalism 50 3.1 Introduction 50 3.2 Micro Professionalism: Pioneering individuals 53 3.3 Meso Professionalism: Growing Internationalism 64 3.4 Macro Professionalism: Women's Champions League 70 3.5 Conclusion: From Germany 2011 to Canada 2015 81 References 86 i Conclusion 90 4.1 Conclusion 90 References 105 Recommendations 109 Appendix 1 Key Dates of European Union 112 Appendix 2 Key Dates for European football 116 Appendix 3 Summary A-Y by national association 122 Bibliography 158 ii Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 Abbreviations and Acronyms AFC Asian Football Confederation AIAW Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women ALFA Asian Ladies Football Association CAF Confédération Africaine de Football CFA People’s Republic of China Football Association China ’91 FIFA Women’s World Championship 1991 CONCACAF Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football CONMEBOL -

CHANGING the GAME: a Critical Analysis of Large-Scale Corruption in Mega Sport Event Infrastructure Projects Author: Maria Da Graça Prado

CHANGING THE GAME: A critical analysis of large-scale corruption in Mega Sport Event infrastructure projects Author: Maria da Graça Prado Abstract Corruption in the delivery of infrastructure for Mega unlocking the black box of how public money is spent. Sport Events (MSEs) seems to have become a common Partnerships with project preparation facilities can mitigate curse. High costs, low levels of monitoring and complex the long-standing issue of poor planning, and an open- logistics create the perfect storm for corruption, repeating book approach to cost management can provide a better a history of malpractice that leaves poor, unsuitable and understanding of contractors’ costs and performance inflated infrastructure as a legacy. Tools for transparency to help improve MSE estimations. Channels to report and collaboration are key allies to changing this game. wrongdoing and integrity pacts tailored to the reality of An open data system can help citizens and civil society MSEs can foster new routes to transparency and reduce to identify red flags in the implementation of projects, the opportunities for corruption. Athletes at the Birds Nest Stadium, Beijing, China Pete Niesen / Shutterstock.com Page 1 Introduction The modus operandi observed over the entire Corruption is an inherent risk of major infrastructure gamut of activities leading to the conduct of the projects. Neil Stansbury lists specific features that make “Games was: inexplicable delays in decision making, which put pressure on timelines and thereby led infrastructure projects particularly prone to corruption, to the creation of an artificial or consciously including their size and unique nature, a complex created sense of urgency. -

List of the Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia for St

List of the Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia for St. Petersburg and the Leningrad Region № Units Addresses п\п 1 Admiralteysky District of Saint 190013, Saint Petersburg Vereyskaya Street, 39 Petersburg 2 Vasileostrovsky District of Saint 199106, Saint Petersburg, Vasilyevsky Island, 19th Line, 12a Petersburg 3 Vyborgsky District of Saint 194156, Saint Petersburg, Prospekt Parkhomenko, 18 Petersburg 4 Kalininsky District of Saint 195297, Saint Petersburg, Bryantseva Street, 15 Petersburg 5 Kirovsky District of Saint 198152, Saint Petersburg, Avtovskaya Street, 22 Petersburg 6 Kolpinsky District of Saint 198152, Saint Petersburg, Kolpino, Pavlovskaya Street, 1 Petersburg 7 Krasnogvardeisky District of 195027, Saint Petersburg, Bolsheokhtinsky Prospekt, 11/1 Saint Petersburg 8 Krasnoselsky District of Saint 198329, Saint Petersburg, Tambasova Street, 4 Petersburg 9 Kurortny District of Saint 197706, Saint Petersburg, Sestroretsk, Primorskoe Highway, Petersburg 280 10 Kronshtadtsky District of Saint 197760, Saint Petersburg, Kronstadt, Lenina Prospekt, 20 Petersburg 11 Moskovsky District of Saint 196135, Saint Petersburg, Tipanova Street, 3 Petersburg 12 Nevsky District of Saint 192171, Saint Petersburg, Sedova Street, 86 Petersburg 13 Petrogradsky District of Saint 197022, Saint Petersburg, Grota Street, 1/3 Petersburg 14 Petrodvortsovy District of Saint 198516, Saint Petersburg, Peterhof, Petersburg Konnogrenaderskaya Street., 1 15 Primorsky District of Saint 197374 Saint Petersburg, Yakhtennaya Street, 7/2 -

Ojsc “Lsr Group” 36 Kazanskaya Street, St

STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL – FOR ADDRESSEE ONLY REPORT AND VALUATION FOR: OJSC “LSR GROUP” 36 KAZANSKAYA STREET, ST. PETERSBURG,190031, RUSSIA OF THE REAL ESTATE PROPERTIES TOGETHER KNOWN AS: “LSR GROUP PORTFOLIO” DATE OF VALUATION: DECEMBER 31, 2011 DATE OF REPORT ISSUE: FEBRUARY 29, 2012 PREPARED BY: OOO CUSHMAN & WAKEFIELD LLC DUCAT PLACE III 6 GASHEKA STREET 125047, MOSCOW, RUSSIA TEL: +7 (495) 797-9600 FAX: +7 (495) 797-9601 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SCOPE OF INSTRUCTIONS ................................................................................................... 3 2. BASIS OF VALUATION ........................................................................................................... 7 3. ASSUMPTIONS AND SOURCES OF INFORMATION ................................................... 7 4. TENURE AND TENANCIES .................................................................................................. 8 5. NET ANNUAL RENT.............................................................................................................. 10 6. TOWN PLANNING ................................................................................................................. 11 7. STRUCTURE .............................................................................................................................. 13 8. SITE AND CONTAMINATION ........................................................................................... 13 9. PLANT AND MACHINERY ................................................................................................. -

Global Opportunities for Sports Marketing and Consultancy Services to 2022

Global opportunities for sports marketing and consultancy services to 2022 Ardi Kolah A management report published by IMR Suite 7, 33 Chapel Street Buckfastleigh TQ11 0AB UK +44 (0) 1364 642224 [email protected] www.imrsponsorship.com Copyright © Ardi Kolah, 2013. All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms and licences issued by the CLA. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside these terms should be sent to the publisher. 2 About the Author Ardi Kolah BA. LL.M, FCIPR, FCIM A marketing and communications practitioner with substantial sports marketing, business and social media experience, he has worked with some of the world’s most successful organisations including Westminster School, BBC, Andersen Consulting (Accenture), Disney, Ford, Speedo, Shell, The Scout Association, MOBO, WPP, Proctor & Gamble, CPLG, Brand Finance, Genworth Financial, ICC, WHO, Yahoo, Reebok, Pepsi, Reliance, ESPN, Emirates, Government of Abu Dhabi, Brit Insurance, Royal Navy, Royal Air Force, Defence Academy, Cranfield University, Imperial College and Cambridge University. He is the author of the best-selling series on sales, marketing and law for Kogan Page, published worldwide in 2013 and is a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Marketing, a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Public Relations, Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Marketors and Chair of its Law and Marketing Committee. -

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year!

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year! NO. 51 (1843) САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГ-ТАЙМС WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 24, 2014 WWW.SPTIMES.RU JULIA REMIZOVA / FOR SPT / FOR JULIA REMIZOVA Skaters slip and slide on the rink in Pionerskaya Ploschad set up as part of a holiday fair that opened on Dec. 19 and will remain open until Jan. 11. The city offi- THE IRONY OF SKATE cially opened the holiday season on Dec. 20 with the lighting of the tree in Dvortsovaya Ploschad as locals prepare for the upcoming New Year celebrations. NEWS NEWS Will Russia’s Facebook Ban FEATURE Economic Woes How to Hurt Other Disappear Countries? Forever The St. Petersburg Times learns how it’s done. Weakening ruble causes Social media website blocks Page 16. recession fears. Page 5. pro-Navalny page. Page 3. News www.sptimes.ru | Wednesday, December 24, 2014 ❖ 2 World’s Biggest Clock Unveiled ALL ABOUT TOWN Wednesday, Dec. 24 people regret their decision to come By Irina Titova English teachers looking to bring in and try to match their intellectual THE ST. PETERSBURG TIMES the holidays with grammatical cor- prowess against yours. The official presentation of the world’s rectness are encouraged to attend biggest clock, which was made at Rus- the British Book Center’s EFL Saturday, Dec. 27 sia’s oldest watch-making factory Ra- Seminar this evening conducted by Get cultural and material simultane- keta located in St. Petersburg’s suburb Evgeniy Kalashnikov, the British ously during the free classical music Petrodvorets, was held in the famed Council regional teacher trainer. concert at the Galeria shopping mall Central Children’s Department Store Register for the event, which begins in the heart of the city.