HISTORICAL REVIEW Downloaded From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ED071097.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 071 097 CS 200 333 TITLE Annotated Index to the "English Journal," 1944-1963. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Champaign, PUB DATE 64 NOTE 185p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Renyon Road, Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock No. 47808, paper, $2.95 non-member, $2.65 member; cloth, $4.50 non-member, $4.05 member) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC -$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies; Educational Resources; English Education; *English Instruction; *Indexes (Locaters); Periodicals; Resource Guides; *Scholarly Journals; *Secondary School Teachers ABSTRACT Biblidgraphical information and annotations for the articles published in the "English Journal" between 1944-63are organized under 306 general topical headings arranged alphabetically and cross referenced. Both author and topic indexes to the annotations are provided. (See also ED 067 664 for 1st Supplement which covers 1964-1970.) (This document previously announced as ED 067 664.) (SW) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. f.N... EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION Cr% THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO. C.) DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- 1:f INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY r REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU C) CATION POSITION OR POLICY [11 Annotated Index to the English Journal 1944-1963 Anthony Frederick, S.M. Editorial Chairman and the Committee ona Bibliography of English Journal Articles NATIONAL COUNCIL OF TEACHERS OF ENGLISH Copyright 1964 National Council of Teachers of English 508 South Sixth Street, Champaign, Illinois 61822 PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS COPY RIGHTED MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRLNTED "National Council of Teachers of English TO ERIC AND ORGANIZATIONS OPERATING UNDER AGREEMENTS WITH THE US OFFICE OF EDUCATION FURTHER REPRODUCTION OUTSIDE THE ERIC SYSTEM REQUIRES PER MISSION OF THE COPYRIGHT OWNER English Journal, official publication for secondary school teachers of English, has been published by the National Council of Teachers of English since 1912. -

Alfred the Great: the Oundf Ation of the English Monarchy Marshall Gaines

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2015 Alfred the Great: The oundF ation of the English Monarchy Marshall Gaines Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Recommended Citation Gaines, Marshall, "Alfred the Great: The oundF ation of the English Monarchy" (2015). Senior Honors Theses. 459. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/459 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. Alfred the Great: The oundF ation of the English Monarchy Abstract Alfred the Great, one of the best-known Anglo-Saxon kings in England, set the foundation for the future English monarchy. This essay examines the practices and policies of his rule which left a asl ting impact in England, including his reforms of military, education, religion, and government in the West Saxon Kingdom. Degree Type Open Access Senior Honors Thesis Department History and Philosophy First Advisor Ronald Delph Keywords Anglo-Saxon, Vikings, Ninth Century, Burgh, Reform This open access senior honors thesis is available at DigitalCommons@EMU: http://commons.emich.edu/honors/459 ALFRED THE GREAT: THE FOUNDATION OF THE ENGLISH MONARCHY By Marshall Gaines A Senior Thesis Submitted to the Eastern Michigan University Honors College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors in History Approved at Ypsilanti, Michigan, on this date 12/17/15 Alfred the Great: The Foundation of the English Monarchy Chapter I: Introduction Beginning in the late eighth century, Northern Europe was threatened by fearsome invasions from Scandinavia. -

Changing Thegns: Cnut's Conquest and the English Aristocracy*

The 1983 Denis Bethell Prize Essay of the Charles Homer Haskins Society Changing Thegns: Cnut's Conquest and the English Aristocracy* Katharin Mack England was conquered twice in the eleventh century: first in 1016 by Cnut the Dane and again in 1066 by William Duke of Normandy. The influence of the Norman Conquest has been the subject of scholarly warfare ever since E.A. Freeman published the first volume of his History of the Nor~ man Conquest of England in 1867-and indeed, long before.' The conse~ quences of Cnut's conquest, on the other hand, have not been subjected to the same scrutiny. Because England was conquered twice in less than fifty years, historians have often succumbed to the temptation of comparing the two events. But since Cnut's reign is poorly documented and was followed quickly by the restoration of the house of Cerdic in the person of Edward the Confessor, such studies have tended to judge 1016 by the standards of 1066. While such comparisons are useful, they have imposed a model on Cnut's reign which has distorted the importance of the Anglo-Scandinavian period. 2 If, however, Cnut's reign is compared with the Anglo-Saxon past rather than the Anglo-Norman future, the influence of 1016 can be more fairly assessed. At first sight, there would seem little to debate. Cnut appears to have adopted wholeheartedly the traditional role of Anglo-Saxon kingship. The sources suggest that at every chance, Cnut proclaimed his determination to be a good English king,3 and modern scholarship has confirmed many of • An abbreviated version of this article was presented at the Haskins Society Conference at the University of Houston, November, 1983. -

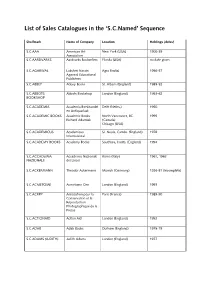

List of Sales Catalogues in the 'S.C.Named' Sequence

List of Sales Catalogues in the ‘S.C.Named’ Sequence Shelfmark Name of Company Location Holdings (dates) S.C.AAA American Art New York (USA) 1900-39 Association S.C.AARDVARKS Aardvarks Booksellers Florida (USA) no date given S.C.AGARWAL Lakshmi Narain Agra (India) 1956-57 Agarwal Educational Publishers S.C.ABBEY Abbey Books St. Albans (England) 1989-92 S.C.ABBOTS Abbots Bookshop London (England) 1953-62 BOOKSHOP S.C.ACADEMIA Academia Boekhandel Delft (Neths.) 1950 en Antiquariaat S.C.ACADEMIC BOOKS Academic Books North Vancouver, BC 1995 Richard Adamiak (Canada) Chicago (USA) S.C.ACADEMICUS Academicus St. Neots, Cambs. (England) 1978 International S.C.ACADEMY BOOKS Academy Books Southsea, Hants. (England) 1994 S.C.ACCADEMIA Accademia Nazionale Rome (Italy) 1961, 1963 NAZIONALE dei Lincei S.C.ACKERMANN Theodor Ackermann Munich (Germany) 1926-81 (incomplete) S.C.ACMETOME Acmetome One London (England) 1993 S.C.ACRPP Association pour la Paris (France) 1989-90 Conservation et la Réproduction Photographique de la Presse S.C.ACTIONAID Action Aid London (England) 1992 S.C.ADAB Adab Books Durham (England) 1975-79 S.C.ADAMS (JUDITH) Judith Adams London (England) 1977 S.C.ADDISON Reginald Addison London (England) no date given S.C.ADDISON WESLEY Addison Wesley Reading, Mass. (USA) 1961, 1962, 1964 Publishing Company S.C.ADER Etienne Ader Paris (France) 1933-67 (incomplete) Ader Picard Tajan 1981-91 S.C.ADLER Arno Adler Lubeck (Germany) no date given S.C.AEGIS Aegis Buch- und (Germany) 1959, 1962, 1964-65 Kunstantiquariat S.C.AEROPHILIA Aerophlia -

A Note on Bcs 538 (S 319)

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society THE DEVOLUTION OF BOOKLAND IN NINTH- CENTURY KENT: A NOTE ON BCS 538 (S 319) RICHARD ABELS A remarkable charter, which has until now escaped the attention it merits, sheds some much needed light on the devolution of bookland upon the lower levels of land-holding society in ninth-century Eng- land. BCS 538 [S 319]' is an eleventh-century text purporting to record a grant of land in Kent by the west Saxon king Aethelwulf. The only suspicious element of this charter is its dating clause. The year given, A.D. 874, is impossible, since Aethelwulf had died sixteen years before. This in itself, however, is not decisive proof of forgery; even undoubtedly genuine diplomas are occasionally misdated.3 Moreover, in the case of this particular charter there is a perfectly reasonable explanation for such an error. BCS 538 contains two sets of confirmatory signatures. Dorothy Whitelock, observing that the first witness list and indiction would agree with A.D. 844, suggests that the scribe altered the date to accord with the appended confirmatory signatures.4 1 BCS 538 = Walter de Gray Birch, (Ed.), Cartularium Saxonicum 2 (1887; repr., New York, 1964), no. 538; S 319 = Peter Sawyer, Anglo-Saxon Charters: An annotated List and Bibliography, Royal Historical Society Guides and Handbooks 8 (London, 1968), no. 319. This charter is now preserved as MS British Museum Stowe Charters, no. 21, and is reproduced in W.B. Sanders, (Ed.), Facsimiles of Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts 3 (Southampton, 1884), no. -

Anglo-Saxon and Norman England, C.1060-1088 Paper 2 British Depth Study

Paper 2 – Anglo-Saxon and Norman England, c.1060-1088 Paper 2 British Depth Study: Anglo-Saxon and Norman England c.1060-88 Name ………………………………………………….. 1 Paper 2 – Anglo-Saxon and Norman England, c.1060-1088 Anglo-Saxon and Norman England – Revision Checklist How well do I know each topic? 3 Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest 4 What was England like in Anglo-Saxon times? 8 Edward the Confessor’s last years 11 1066 and the rival claimants for the throne 13 The Norman invasion 15 Topic Test – Theme 1: Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest 16 William I in Power: Securing the Kingdom, 1066-87 17 Establishing control 20 Anglo-Saxon resistance, 1068-71 22 The legacy of resistance to 1087 25 Revolt of the Earls, 1075 27 Topic Test – Theme 2: Securing the Kingdom, 1066-87 29 Norman England, 1066-88 30 The feudal system 32 The Church 35 Norman government 37 Norman aristocracy 39 William I and his sons 41 Topic Test – Theme 3: Norman England, 1066-88 Produced by J. Harris, Sir Harry Smith Community College 2 Paper 2 – Anglo-Saxon and Norman England, c.1060-1088 Theme 1: Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest, 1060-66 3 Paper 2 – Anglo-Saxon and Norman England, c.1060-1088 What was England like in Anglo-Saxon times? England had a population of about 2 million people (less than half of London today!) Almost everyone farmed land. England was a Christian country, and religion played a large role in everyday life. For centuries England had been under threat from the Vikings, and parts of northern England had Viking settlers. -

Ealdorman Byrhtnoth and the Brayfield Charter of 967. Arnold

EALDORMANBYRHTNOTHANDTHEBRAYAELD CHARTER OF 967 ARNOLD H. J. BAINES Cold Brayfield and Brafield on the Green both have claims to be the Bragenfeld granted by King Edgar in 967 toByrhtnoth, ealdorman ofEssex, who was to be the hero ofthe battle ofMaldon. The derivation ofthis difficult name is discussed; it is considered to relate to a tract of/and clearedfrom Yardley forest and including the sites of both villages. Reasons are suggested for the grant, and for the absence ofa hidage assessment and ofa boundary survey. The charter, preserved in an Abingdon cartulary, is placed in its historical context, and shown to be based on a landbook of 964 granting land at Coakley (Wares) to Byrhtnoth, with significant textual differences, probably made at his instance. The dating ofdiplomas by the year of grace and the indictional year is discussed. In 967 King Edgar, with the consent of the Witan, decision when dying on the field of Maldon (11 granted to his ealdorman Byrhtnoth an estate in the August 991) and also gave Ramsey one hide at locality called Bragenfeld. The original membrane Denton. The contemporary poem on the battle 12 has not survived, but the charter was copied into a leaves no time for Byrhtnoth to make a nuncupative thirteenth-century cartulary of Abingdon Abbey. 1 will between his death-wound and his memorable The transcript has no boundary survey and lacks a last words; however, the Ramsey account may reflect numeral which would have stated the assessment in not what he then said but what his widow did to fulfil hides, so that the suggestion that the grant relates to his known or presumed intentions. -

'A Mere Clerk': Representing the Urban Lower-Middle-Class

‘A MERE CLERK’: REPRESENTING THE URBAN LOWER-MIDDLE-CLASS MAN IN BRITISH LITERATURE AND CULTURE: 1837-1910. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Scott Douglass Banville, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Approved by Dissertation Committee: Professor David G. Riede, Adviser Adviser Professor Clare Simmons English Graduate Program Professor Amanpal Garcha ABSTRACT My dissertation explores the various ways in which the lower middle class is represented in the Victorian period. Drawing on literary texts by Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope, and George Gissing and non-literary texts appearing in periodicals, comic newspapers, and music-hall songs I show how the lower middle class consisting of those members of British society working variously as Civil Service, commercial, and retail clerks, school teachers, and living in the suburbs of London and other large cities is represented as dangerous, laughable, and pitiable. Through readings of self-improvement books by Samuel Smiles, conduct and instruction manuals, and didactic literature I show how middle-class anxieties about its own position vis-à-vis the aristocracy and the working class drive middle-class elites and its representatives to represent the lower middle class as dangerous and thus in need of containment and surveillance. One of the constant fears of the middle class is that the lower middle class will develop a cultural and economic identity of its own and as a result will over shadow the middle class. Often times this middle-class anxiety is cloaked in moral concern. -

Patrick Wormald Papers Preparatory to the Making of English

Patrick Wormald Papers Preparatory to The Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century Volume II From God’s Law to Common Law Edited by Stephen Baxter and John Hudson UNIVERSITY OF LONDON EARLY ENGLISH LAWS 2014 Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON EARLY ENGLISH LAWS http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk © Patrick Wormald 2014 ISBN 978-1-909646-03-2 Contents Preface v Abbreviations vi Editorial Introduction xi PART III: THE ORIGINS OF AN ENGLISH ROYAL LAW 1 Chapter 7B. Re-introductory: The Limits of Legislative Evidence 1 Chapter 8. Church and King 16 What is due to God 18 (i) Church taxation 18 (ii) Fast and Festival 54 (iii) Continence 64 What is due from God 72 (i) Ordeal 72 (ii) Reprieve and Pardon 90 Chapter 9. The Pursuit of Crime 98 The Meaning of Treason 100 (i) Forfeiture 100 (ii) The Oath 112 (iii) Burials 129 The Quality of Mercy 141 The Dynamics of Prosecution 161 Chapter 10. The Machinery of Justice 192 Introductory 192 Shire and Hundred 192 (i) Courts before the Tenth Century 192 (ii) The Tenth Century Revolution in Local Government 193 Centre and Locality 198 ‘Public’ and ‘Private’ 201 (i) The ‘Pleas of the Crown’ 202 (ii) The Judicial Duties and Perquisites of Lordship 204 (iii) ‘Sake and Soke’: the Private Hundred 208 Chapter 11. The Foundations of Title 212 ‘Bookland and Folkland’ 212 (i) Folkland 212 (ii) Bookland 214 The role of the king 217 Heirs and Legatees 220 (i) Wills 220 (ii) Litigation 226 (iii) Inheritance 226 Tenant and Lord 228 Chapter 12. -

Representations of Anglo-Saxon England in Children's Literature

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2004-12-15 Representations of Anglo-Saxon England in Children's Literature Kirsti A. Bobo Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Bobo, Kirsti A., "Representations of Anglo-Saxon England in Children's Literature" (2004). Theses and Dissertations. 228. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/228 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REPRESENTATIONS OF ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE By Kirsti Ann Bobo A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English Brigham Young University December 2004 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Kirsti Ann Bobo This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. Date Zina N. Petersen, Chair Date Don W. Chapman Date Jacqueline Thursby BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY As chair of the candidate’s graduate committee, I have read the thesis of Kirsti A. Bobo in its final form and have found that (1) its format, citations, and bibliographical style are consistent and acceptable and fulfill university and department style requirements; (2) its illustrative materials including figures, tables, and charts are in place; and (3) the final manuscript is satisfactory to the graduate committee and is ready for submission to the university library. -

Development of Crime in Early English Society, the Clarence Ray Jeffery

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 47 | Issue 6 Article 2 1957 Development of Crime in Early English Society, The Clarence Ray Jeffery Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Clarence Ray Jeffery, Development of Crime in Early English Society, The, 47 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 647 (1956-1957) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE DEVELOPMENT OF CRIME IN EARLY ENGLISH SOCIETY CLARENCE RAY JEFFERY The author is Lecturer in Sociology in the Southern Illinois University at Carbon- dale. He has been making a study of law and English society with a view to understand- ing what relationship there may be between crime and social structure. His article entitled, "The Structure of American Criminological Thinking" is published in this Journal, Vol. 46, at pages 658 ff.-January-February, 1956. A second contribution under his authorship entitled, "Crime, Law and Social Strictures" was published in Vol. 47-November-December, 1956.-EDITOR. The purpose of this paper is to trace the development of crime and criminal law in England from 400 A.D. to 1200 A.D. This period of history was selected for two reasons. First, early Saxon laws were recorded, and thus the changes which occurred inthe legal structure over a period of years can be traced and analyzed; and second, it was during this period of English history that the tribal law of the Saxons gave way to the common law system which is now basic to Anglo-American law. -

The Monastic Research Bulletin, Issue 13

MONASTIC RESEARCH BULLETIN Published at the end of each calendar year. Subscriptions (£4/year) and correspondence to the Borthwick Institute, University of York, Heslington, York, YO10 5DD. All enquiries regarding subscriptions and back numbers should be sent to the Borthwick at this address. Editorial contributions only should be sent to the Editor, Dr Martin Heale, School of History, University of Liverpool, 9 Abercromby Square, Liverpool, L69 7WZ; email: [email protected] Standing Committee: Dr Andrew Abram, Dr Janet Burton, Dr Glyn Coppack, Professor Claire Cross, Professor Barrie Dobson, Professor Joan Greatrex, Dr Martin Heale (editor), Professor David Smith. CONTENTS OF ISSUE 13 (2007) (ISSN 1361-3022) Julian Haseldine, A Lost Letter of Peter of Celle, p.1; Nicholas Orme, Monks of the Furthest West, p.8; David Austin, A New Project at Strata Florida, Ceredigion, Wales, p.13; Anne Müller, A New International Research Centre for the Comparative History of Religious Orders in Eichstätt (Germany), p.21; Caroline Bowden, History of Women Religious of Britain and Ireland, p.24; Sophia Deboick, Conference Report: Consecrated Women: Towards a History of Women Religious of Britain and Ireland, p.26; Janet Burton, The Regular Canons in the British Isles in the Middle Ages, p.29; Liz Eastlake, The History of Boxley Abbey 1146- 1538, p.32; Michele Moatt, Walter Daniel’s Life of Aelred of Rievaulx Re-Considered, p.34; Emily Bannister, Peter Damian (c.1007-1072), Monastic Ideology and the Religious Revolution of the Eleventh Century, p.36; Christian Steer, Commemoration in the Religious Houses of London, p.39; Select Bibliography, p.42.