The Monastic Research Bulletin, Issue 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diocese of Phoenix (Dioecesis Phoenicensis)

1047 Diocese of Phoenix (Dioecesis Phoenicensis) Most Reverend THOMAS J. OLMSTED, J.C.D. Bishop of Phoenix; ordained July 2, 1973; appointed Coadjutor Bishop of Wichita February 16, 1999; Episco- pal ordination April 20, 1999; appointed Bishop of Wichita October 4, 2001; appointed Bishop of Phoenix Most Reverend November 25, 2003; installed December 20, 2003. Office: 400 E. Monroe St., Phoenix, AZ 85004-2336. EDUARDO A. NEVARES Auxiliary Bishop of Phoenix; ordained July 18, 1981; appointed Titular Bishop of Natchesium and Auxiliary Bishop of Phoenix May 11, 2010; episcopal ordination July 19, 2010. Office: 400 E. Monroe St., Phoenix, AZ Most Reverend 85004-2336. THOMAS J. O’BRIEN ESTABLISHED DECEMBER 2, 1969. Bishop Emeritus of Phoenix; ordained May 7, 1961; Square Miles 43,967. consecrated January 6, 1982; installed January 18, Comprises the Counties of Maricopa; Mohave; Yavapai 1982; retired June 18, 2003. Mailing Address: 400 E. & Coconino not to include the territorial boundaries of Monroe St., Phoenix, AZ 85004-2336. the Navajo Indian Reservation; Pinal--that portion of land known as the Gila River Indian Reservation in the State of Arizona. Patroness of Diocese: Our Lady of Guadalupe. For legal titles of parishes and diocesan institutions, consult the Chancery Office. Diocesan Pastoral Center: 400 E. Monroe St., Phoenix, AZ 85004-2336. Tel: 602-257-0030; 602-354-2000; Fax: 602-354-2427. Web: www.diocesephoenix.org Email: [email protected] STATISTICAL OVERVIEW Personnel Brothers....................... 2 Elementary Schools, Diocesan and Parish 36 Bishop. ........................ 1 Sisters......................... 33 Total Students................... 9,091 Auxiliary Bishops. ................ 1 Lay Ministers................... 1,780 Catechesis/Religious Education: Retired Bishops. -

The Society for the Propagation of the Faith National Director’S Message Mission Today Message Spring 2016

Vol. 75, No. 2 Spring 2017 InIn ThisThis IssueIssue Project Africa: We visit Uganda, Kenya and Ghana Baptisms in Ethiopia Chalice Program at work in Uganda Celebrating Sister Mary Ellen Burns CSJ Elizabeth Shultz: Making a Difference The Society for the Propagation of the Faith National Director’s Message Mission Today Message Spring 2016 By the time you receive the Pope Francis for her dedication to the Holy Childhood Associa- spring edition of Mission To- tion and Catholic schools in the Archdiocese of Vancouver. There day the Universal Church will are mission stories about the projects being supported by you, our be in the season of Lent, a time donors. These stories are hope filled accounts about the faith com- set apart to give serious thought mitment of missionaries like the Sisters of Loreto whose first sisters to things that the world around arrived in India 175 years ago from Ireland. In this issue, the work us refuses to consider. Lent is a of the Pontifical Society of St Peter the Apostle and those helped favourable time to deepen our by it are highlighted. This society supports the training and edu- spiritual life through fasting, cation of future leaders of the mission church. Through the work prayer and almsgiving, each a of the Society of St. Peter the Apostle, seminarians and religious route to holiness offered us by are provided with resources, books, food and housing. Without the Church. At the centre of this support many of our brothers and sisters in mission countries everything is the word of God and during this season of Lent, would not be able to continue this important mission endeavour. -

Tavistock Abbey

TAVISTOCK ABBEY Tavistock Abbey, also known as the Abbey of Saint Mary and Saint Rumon was originally constructed of timber in 974AD but 16 years later the Vikings looted the abbey then burned it to the ground, the later abbey which is depicted here, was then re-built in stone. On the left is a 19th century engraving of the Court Gate as seen at the top of the sketch above and which of course can still be seen today near Tavistock’s museum. In those early days Tavistock would have been just a small hamlet so the abbey situated beside the River Tavy is sure to have dominated the landscape with a few scattered farmsteads and open grassland all around, West Down, Whitchurch Down and even Roborough Down would have had no roads, railways or canals dividing the land, just rough packhorse routes. There would however have been rivers meandering through the countryside of West Devon such as the Tavy and the Walkham but the land belonging to Tavistock’s abbots stretched as far as the River Tamar; packhorse routes would then have carried the black-robed monks across the border into Cornwall. So for centuries, religious life went on in the abbey until the 16th century when Henry VIII decided he wanted a divorce which was against the teachings of the Catholic Church. We all know what happened next of course, the Dissolution of the Monasteries, when along with all the other abbeys throughout the land, Tavistock Abbey was raised to the ground. Just a few ruined bits still remain into the 21st century. -

Mother Teresa: Holiness in the Dark by J.I

KNOWING . OING &DC S L EWIS INSTITUTE Spring 2009 A Teaching Quarterly for Discipleship of Heart and Mind PROFILE IN FAITH Mother Teresa: Holiness in the Dark by J.I. Packer, M.A., D.Phil. Author and Theologian The men of the East may spell the stars, death in 1997 at the age of 87, has recently IN This Issue And times and triumphs mark, highlighted this perplexing reality, and the 2 Notes from the But the men signed of the cross of Christ easiest way to present the problem is to re- President Go gaily in the dark. view her story. by Tom Tarrants Night shall be thrice night over you, Darkness: the Personal Distress 3 Lessons on Grace And heaven an iron cope. in a Valley of Grief Do you have joy without a cause, Born Gonxha Agnes Bojaxhiu in Skopje, Yu- by Kristie Jackson Yea, faith without a hope? goslavia (now part of the Republic of Mace- G.K. Chesterton, The Ballad of the White Horse donia), she loved Jesus and wanted to be a 4 Evangelical, But missionary from a very early age. At 18 she Not Evangelistic by Stuart McAllister Who among you fears the Lord and obeys the left for Ireland to join the Sisters of Loreto, an word of his servant? Let him who walks in the education-oriented community whose work 6 Is Jesus Really the dark, who has no light, trust in the name of in India she hoped to share. She went to Cal- Only Way to God? the Lord and rely on his God. -

PDZ1 Final Report Intro

PDZ: 1 Rame Head to Pencarrow Head Management Area 01 Management Area 02 Management Area 03 Aerial view of Polperro Rame Head to Pencarrow Head This section of coast generally faces south or south west. It mainly comprises hard, rocky cliffs fronted by shore platforms, sand/shingle beaches and incised valleys with streams discharging to the coast. The largest beach is Long Sand at Whitsand Bay, with a few smaller pocket beaches including Millendreath Beach and Seaton Beach. Tidal inlets exist at Seaton, Looe and Polperro. Commercial interests other than tourism and recreation in the area are the commercial fishing fleet at Looe, and agriculture along the cliff top. This is a relatively undeveloped rural and agricultural part of the Cornish coast comprised mainly of grassland and arable land, with some woodland. This area is valued for its costal habitats, rare plants, historic sites and important geomorphological processes. Cornwall and Isles of Scilly SMP2 Final Report Chapter 4 PDZ1 1 February 2011 Cornwall and Isles of Scilly SMP2 Final Report Chapter 4 PDZ1 2 February 2011 General Description Built Environment Fixed assets at the coast increase towards the west, with the coastal settlements at Portwrinkle, Downderry, Seaton, Millendreath, Plaidy, East and West Looe and Hannafore, Talland and Polperro. The main settlement of the area is Looe. Downderry Heritage The Rame Peninsula is the site of an important cluster of post-medieval fortifications including a group of scheduled monuments. There is also an Iron Age settlement at Rame and there are medieval field strips close to Tregantle fort. A group of Bronze Age barrows are situated close to the cliff east of Downderry, with other historic and archaeologically valuable sites and scattered archaeological remains between Polperro and Polruan. -

A Visitors' Guide to Our Saints

A Visitors’ Guide to Our Saints Welcome to Holy Name of Jesus Cathedral We are grateful that you have decided to visit the Cathedral today and welcome you to our spiritual home. Please take a few minutes to read the following guidelines before continuing into the worship space of the church. This guide follows the order of the saint statues in their respective places, starting in the left loggia, continuing along the left perimeter of the nave, up to the left transept and around close to the sanctuary. Crossing in front of the altar, (not through) resume your path in the right transept to the right of the sanctuary, along the back wall, the near wall and then the right perimeter of the nave. Visitor Guidelines The Cathedral is a non-smoking facility and is, first and foremost, a religious space. Please respect our traditions and especially the presence of others praying or those touring the Cathedral during your visit. Additionally: ◊ No food is allowed in the church, including gum or drinks. ◊ Please keep voices low as there may be others praying. ◊ Gentlemen, please remove hats. ◊ Please refrain from using your mobile phone for purposes other than photography. ◊ Please do not enter closed areas. (The sanctuary, cathedra, altar, sacristies, choir loft and bell tower are not accessible to visitors.) ◊ Photography is not permitted during services but is allowed at all other times. 2 May 2018 St. John Vianney—August 4 [1] St. John Vianney, T.O.S.F. (1786-1859) John grew up amid the Terror of the French Revolution, so first learned and practiced the faith in secret. -

NEWSLETTER September 2019

President: Secretary: Treasurer: David Illingworth Nigel Webb Malcolm Thorning 01305 848685 01929 553375 01202 659053 NEWSLETTER September 2019 FROM THE HON. SECRETARY Since the last Newsletter we have held some memorable meetings of which the visit, although it was a long and tiring day, to Buckfast Abbey must rank among the best we have had. Our visit took place on Thursday 16th May 2019 when some sixteen members assembled in the afternoon sunshine outside the Abbey to receive a very warm welcome from David Davies, the Abbey Organist. He gave us an introduction to the acquisition and building of the organ before we entered the Abbey. The new organ in the Abbey was built by the Italian firm of Ruffatti in 2017 and opened in April 2018. It has an elaborate specification of some 81 stops spread over 4 manuals and pedals. It is, in effect, two organs with a large west-end division and a second extensive division in the Choir. There is a full account of this organ in the Organist’s Review for March 2018 and on the Abbey website. After the demonstration we were invited to play. Our numbers were such that it was possible for everyone to take the opportunity. David was on hand to assist with registration on this complex instrument as the console resembled the flight deck of an airliner. Members had been asked to prepare their pieces before-hand and this worked well with David commenting on the excellent choice of pieces members had chosen to suit the organ. We are most grateful to David Davies for making us so welcome and help throughout the afternoon. -

Parish Newsletter WE 9 September 2018

MMAAYYOOBBRRIIDDGGEE PPAARRIISSHH BBUULLLLEETTIINN Sunday 9th September 2018 Twenty-Third Sunday in Ordinary Time ‘He makes the deaf hear and the dumb speak’ Mark 7:31-37 ENJOY GRANDPARENTS DAY - TODAY SUNDAY 9TH SEPTEMBER Sunday 9th September 2018 TWENTY-THIRD SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME (41-2018) (Sunday Readings Cycle B – Weekday Cycle 1) PLEASE NOTE Due to the new Data Protection Regulations in our hospitals, a patient list will no longer be made available to the Priests. In light of this could you please let us know if you have someone in hospital to be visited by contacting Fr Desmond Mooney: 02841772200 or Fr Tom: 02840630306.If you get the answering machine, please give the Name of the person, the Hospital and if possible the Ward number. PARISH OFFICE - Open Monday to Thursday 10.00am to 2.00pm For Anniversaries, Marriages or Baptisms phone 028 3085 0270 WEBSITE ADDRESS www.mayobridgeparish.com Bulletin News to Daniel Morgan 07929568392 or email [email protected] by Wednesday evening Email Information for parish website to [email protected] Parish website and webcam now functioning for the sick and housebound and for those who live far from home www.mayobridgeparish.com AL-NON FAMILY GROUP 028 9068 2368 www.al-anonuk.org.uk THE PARISH PASTORAL COUNCIL email address is: [email protected] should a parishioner or visitor to the Parish wish to contact them SAFEGUARDING CHILDREN - Designated person for Dromore Diocese: Patricia Carville 07789917741 Action on Elder Abuse Northern Ireland www.elderabuse.org/northernireland Freephone helpline 08 08 088141 Parish Hall - to book contact Thomas Gallagher 07831 272638 RECENTLY BAPTISED - We welcome into our faith community Oisin James Murphy, 14 Ballyvalley Road. -

The Network RSCM Events in Your Local Area June – October 2016

the network RSCM events in your local area June – October 2016 The Network June 2016.indd 1 16/05/2016 11:17:47 Welcome THE ROYAL SCHOOL OF You can travel the length and CHURCH MUSIC breadth of the British Isles this Registered Charity No. 312828 Company Registration No. summer, participate in and 00250031 learn about church music in 19 The Close, Salisbury SP1 2EB so many forms with the RSCM. T 01722 424848 I don’t think I’ve ever seen quite F 01722 424849 E [email protected] so varied and action-packed an W www.rscm.com edition of The Network. I am Front cover photograph: most grateful to the volunteers on the RSCM’s local Area RSCM Ireland award winners committees, and I hope you will feel able to take up this recording for an RTÉ broadcast, oering. November 2015 How to condense it? Awards, BBC broadcast, The Network editor: Contemporary worship music, Diocesan music day, Cathy Markall Evensongs, Food-based events, Gospel singing, Harvest Printed in Wales by Stephens & George Ltd anthems, Instrumental music, John Rutter, Knighton pilgrimage, Lift up your Voice, Music Sunday, National Please note that the deadline for submissions to the next courses, explore the Organ, converting Pianists, edition of The Network is celebrating the Queen’s birthday, Resources for small and 1 July 2016. rural churches, Singing breaks, Training organists, Using the voice well, Vespers, Workshops, events for Young ABOUT THE RSCM people. Excellence and zeal, I hope. The RSCM is a charity Don’t forget that there is also the triennial committed particularly to International Summer School in Liverpool in August promoting the study, practice and improvement of music at which you can experience many of these things in in Christian worship. -

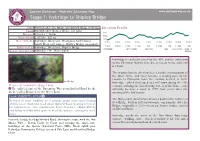

Stage 1-Route-Guide-V3.Cdr

O MO R T W R A A Y D w w k u w . o .d c ar y. tmoorwa Start SX 6366 5627 Ivy Bridge on Harford Road, Ivybridge Elevation Profile Finish SX 6808 6289 Shipley Bridge car park 300m Distance 10 miles / 16 km 200m 2,037 ft / 621 m Total ascent 100m Refreshments Ivybridge, Bittaford, Wrangaton Golf Course, 0.0km 2.0km 4.0km 6.0km 8.0km 10.0km 12.0km 14.0km 16.0km South Brent (off route), Shipley Bridge (seasonal) 0.0mi 1.25mi 2.5mi 3.75mi 5mi 6.25mi 7.5mi 8.75mi 10mi Public toilets Ivybridge, Bittaford, Shipley Bridge IVYBRIDGE BITTAFORD CHESTON AISH BALL GATE SHIPLEY Tourist information Ivybridge (The Watermark) BRIDGE Ivybridge is easily accessed via the A38, and the only town on the Dartmoor Way to have direct access to the main rail network. The original hamlet developed at a handy crossing point of the River Erme, and later became a staging post on the London to Plymouth road; the railway arrived in 1848. Ivy Bridge Ivybridge - which developed as a mill town during the 19th Please refer also to the Stage 1 map. century, utilising the fast-flowing waters of the Erme - only S The official start of the Dartmoor Way is on Harford Road by the officially became a town in 1977, four years after the medieval Ivy Bridge over the River Erme. opening of the A38 bypass. POOR VISIBILITY OPTION a The Watermark (local information) is down in the town near In times of poor visibility or if anxious about your route-finding New Bridge, built in 1823 just downstream from the older Ivy abilities over moorland head down Harford Road, bearing left near Bridge, originally a 13th-century packhorse bridge, passed the bottom to meet the roundabout. -

ED071097.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 071 097 CS 200 333 TITLE Annotated Index to the "English Journal," 1944-1963. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Champaign, PUB DATE 64 NOTE 185p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Renyon Road, Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock No. 47808, paper, $2.95 non-member, $2.65 member; cloth, $4.50 non-member, $4.05 member) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC -$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies; Educational Resources; English Education; *English Instruction; *Indexes (Locaters); Periodicals; Resource Guides; *Scholarly Journals; *Secondary School Teachers ABSTRACT Biblidgraphical information and annotations for the articles published in the "English Journal" between 1944-63are organized under 306 general topical headings arranged alphabetically and cross referenced. Both author and topic indexes to the annotations are provided. (See also ED 067 664 for 1st Supplement which covers 1964-1970.) (This document previously announced as ED 067 664.) (SW) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. f.N... EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION Cr% THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO. C.) DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- 1:f INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY r REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU C) CATION POSITION OR POLICY [11 Annotated Index to the English Journal 1944-1963 Anthony Frederick, S.M. Editorial Chairman and the Committee ona Bibliography of English Journal Articles NATIONAL COUNCIL OF TEACHERS OF ENGLISH Copyright 1964 National Council of Teachers of English 508 South Sixth Street, Champaign, Illinois 61822 PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS COPY RIGHTED MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRLNTED "National Council of Teachers of English TO ERIC AND ORGANIZATIONS OPERATING UNDER AGREEMENTS WITH THE US OFFICE OF EDUCATION FURTHER REPRODUCTION OUTSIDE THE ERIC SYSTEM REQUIRES PER MISSION OF THE COPYRIGHT OWNER English Journal, official publication for secondary school teachers of English, has been published by the National Council of Teachers of English since 1912. -

Alfred the Great: the Oundf Ation of the English Monarchy Marshall Gaines

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2015 Alfred the Great: The oundF ation of the English Monarchy Marshall Gaines Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Recommended Citation Gaines, Marshall, "Alfred the Great: The oundF ation of the English Monarchy" (2015). Senior Honors Theses. 459. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/459 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. Alfred the Great: The oundF ation of the English Monarchy Abstract Alfred the Great, one of the best-known Anglo-Saxon kings in England, set the foundation for the future English monarchy. This essay examines the practices and policies of his rule which left a asl ting impact in England, including his reforms of military, education, religion, and government in the West Saxon Kingdom. Degree Type Open Access Senior Honors Thesis Department History and Philosophy First Advisor Ronald Delph Keywords Anglo-Saxon, Vikings, Ninth Century, Burgh, Reform This open access senior honors thesis is available at DigitalCommons@EMU: http://commons.emich.edu/honors/459 ALFRED THE GREAT: THE FOUNDATION OF THE ENGLISH MONARCHY By Marshall Gaines A Senior Thesis Submitted to the Eastern Michigan University Honors College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors in History Approved at Ypsilanti, Michigan, on this date 12/17/15 Alfred the Great: The Foundation of the English Monarchy Chapter I: Introduction Beginning in the late eighth century, Northern Europe was threatened by fearsome invasions from Scandinavia.