Mutations of the Vampire Motif in the Nineteenth Century Megan Bryan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

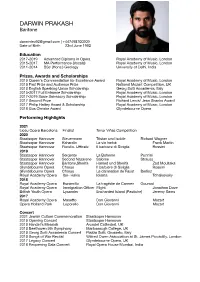

Darwin Prakash CV July 2021

DARWIN PRAKASH Baritone [email protected] | +447498700209 Date of Birth 23rd June 1993 Education 2017-2019 Advanced Diploma in Opera Royal Academy of Music, London 2015-2017 MA Performance (Vocals) Royal Academy of Music, London 2011-2014 BSc (Hons.) Geology University of Delhi, India Prizes, Awards and Scholarships 2019 Queen's Commendation for Excellence Award Royal Academy of Music, London 2019 First Prize and Audience Prize National Mozart Competition, UK 2018 English Speaking Union Scholarship Georg Solti Accademia, Italy 2015-2017 Full Entrance Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017-2019 Susie Sainsbury Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017 Second Prize Richard Lewis/ Jean Shanks Award 2017 Philip Hattey Award & Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2016 Gus Christie Award Glyndebourne Opera Performing Highlights 2021 Liceu Opera Barcelona Finalist Tenor Viñas Competition 2020 Staatsoper Hannover Steuermann Tristan und Isolde Richard Wagner Staatsoper Hannover Kaherdin Le vin herbé Frank Martin Staatsoper Hannover Fiorello, Ufficale Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini 2019 Staatsoper Hannover Sergente La Boheme Puccini Staatsoper Hannover Second Nazarene Salome Strauss Staatsoper Hannover Baritone,Sherifa Hamed und Sherifa Zad Moultaka Glyndebourne Opera Chorus Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini Glyndebourne Opera Chorus La damnation de Faust Berlioz Royal Academy Opera Ibn- Hakia Iolanta Tchaikovsky 2018 Royal Academy Opera Escamillo La tragédie de Carmen Gounod Royal Academy Opera Immigration Officer Flight Jonathan Dove British Youth Opera Lysander Enchanted Island (Pastiche) Jeremy Sams 2017 Royal Academy Opera Masetto Don Giovanni Mozart Opera Holland Park Leporello Don Giovanni Mozart Concert 2021 Jewish Culture Commemoration Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Opening Concert Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Handel's Messiah Arundel Cathedral, UK 2018 Beethoven 9th Symphony Marlborough College, UK 2018 Georg Solti Accademia Concert Piazza Solti, Grosseto, Italy 2018 Songs of War Recital Wilfred Owen Association at St. -

103830767.23.Pdf

•Mi IffjwawmT ,i,>gT-III - •ji. •■m»,i '^i-Wj """"m^m.. ^SS^^' a. u'h\. J6g THE ATTEMPT A LITERARY MAGAZINE CONDUCTED BY THE MEMBEIIS OF THF. EDINBURGH ESSAY SOCIETY. VOLUME IV. "AUSPICIUM MELIORTS MN l: PRINTED FOR THE EDINBURGH ESSAY SOCIETY. COLSTON & SON, EDINBURGH. MDCCCLXVIII. CONTENTS. (.-■^'^ PAGE A Few Thoughts about Newspapers, by Zoe, ..... 107 A Little Learning, by M. L., . 25 An Hour's Musings in an Old Library, by Lutea Reseda, 185 A Royalist, by Mas Alta, .... 134 A Slight Sketch of Ulrich von Hutten, by Zoe, . 282 A Song of the Forest, by Mas Alta, 184 A Thousand Miles, by Mas Alta, 257 A Visit from the Frog, by Frucaxa, 30 Cloris and Daphne, an Idyll, by Lutea Reseda, 13 Claymore, by Mae Alta, .... 109 Contemporary Poets, by des Eaux, 121 Don Pedro's Bride, by Mas Alta, 153 Forgotten Friends, by Agnella, 64 Fragments of a Life, by Enai, 98 From Malta to Aden, by Elsie Strivelyne, 155 Giving Back, by 0. M., .... 113 Hector's Departure, from the German of Schiller, by Dido, . 128 Hope and Memory, by E. H. S., . 209 Hubert's Letters, being MSS. Tempore Caroli Primi, now first published , by Mas J ata, 20, 14, 67, 92 In an Orchard, by Mas Alta, .... 226 In Memoriam, by Alma, .... 71 Islands, by Enai,, . 214 ii CONTENTS. PAGE Knowledge of Ignorance, by des Eaux, .... 118 Lines, by Veronica, ... , 117 Longings, by R. M., ..... 119 " Love me Little, Love me Long," by Dido, 247 Monument to Two Children, by Chantrey, by E. -

Kierkegaard and Byron: Disability, Irony, and the Undead

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2015 Kierkegaard And Byron: Disability, Irony, And The Undead Troy Wellington Smith University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Troy Wellington, "Kierkegaard And Byron: Disability, Irony, And The Undead" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 540. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/540 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KIERKEGAARD AND BYRON: DISABILITY, IRONY, AND THE UNDEAD A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English The University of Mississippi by TROY WELLINGTON SMITH May 2015 Copyright © 2015 by Troy Wellington Smith ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT After enumerating the implicit and explicit references to Lord Byron in the corpus of Søren Kierkegaard, chapter 1, “Kierkegaard and Byron,” provides a historical backdrop by surveying the influence of Byron and Byronism on the literary circles of Golden Age Copenhagen. Chapter 2, “Disability,” theorizes that Kierkegaard later spurned Byron as a hedonistic “cripple” because of the metonymy between him and his (i.e., Kierkegaard’s) enemy Peder Ludvig Møller. Møller was an editor at The Corsair, the disreputable satirical newspaper that mocked Kierkegaard’s disability in a series of caricatures. As a poet, critic, and eroticist, Møller was eminently Byronic, and both he and Byron had served as models for the titular character of Kierkegaard’s “The Seducer’s Diary.” Chapter 3, “Irony,” claims that Kierkegaard felt a Bloomian anxiety of Byron’s influence. -

Hegelian Master-Slave Dialectics: Lord Byron's Sardanapalus

English Language and Literature Studies; Vol. 3, No. 1; 2013 ISSN 1925-4768 E-ISSN 1925-4776 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Hegelian Master-Slave Dialectics: Lord Byron’s Sardanapalus Marziyeh Farivar1, Roohollah R. Sistani1 & Masoumeh Mehni2 1 School of Language studies and Linguistics, UKM, Malaysia 2 University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia Correspondence: Marziyeh Farivar, School of Language Studies and Linguistics (PPBL), Faculty of Social Science and Humanities (FSSK), University Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia. Tel: 60-173-264-628. E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 12, 2012 Accepted: January 3, 2013 Online Published: January 17, 2013 doi:10.5539/ells.v3n1p16 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ells.v3n1p16 Abstract This paper intends to discuss Byron’s “Sardanapalus” by focusing on the Hegelian master-slave dialectics. Written in 1821, “Sardanapalus” presents some trends about Lord Byron’s creation of the Byronic Hero. The Byronic hero is emotional, dreamy, and impulsive. Sardanapalus, the Byronic hero, is the Assyrian King who possesses the complicated nature of both master and slave which is the focus of this article. There are encounters of masters and slaves that consciously and unconsciously take place in this dramatic verse. Sardanapalus’ relationships to his mistress, his brother-in-law and the citizens involve a complex thesis and anti-thesis. Hegelian dialectics reflect the processes of recognition of consciousness through such thesis and anti-thesis. Bondage and lordship and dependency and independency are concepts that are within these processes. Hegel explains that the identity and role of the master and slave can be recognized when they are interacting. -

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S. Pinafore Friday, May 5, 2017, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Albert Bergeret, artistic director in H.M.S. Pinafore or The Lass that Loved a Sailor Libretto by Sir William S. Gilbert | Music by Sir Arthur Sullivan First performed at the Opera Comique, London, on May 25, 1878 Directed and conducted by Albert Bergeret Choreography by Bill Fabis Scenic design by Albère | Costume design by Gail Wofford Lighting design by Benjamin Weill Production Stage Manager: Emily C. Rolston* Assistant Stage Manager: Annette Dieli DRAMATIS PERSONAE The Rt. Hon. Sir Joseph Porter, K.C.B. (First Lord of the Admiralty) James Mills* Captain Corcoran (Commanding H.M.S. Pinafore) David Auxier* Ralph Rackstraw (Able Seaman) Daniel Greenwood* Dick Deadeye (Able Seaman) Louis Dall’Ava* Bill Bobstay (Boatswain’s Mate) David Wannen* Bob Becket (Carpenter’s Mate) Jason Whitfield Josephine (The Captain’s Daughter) Kate Bass* Cousin Hebe Victoria Devany* Little Buttercup (Mrs. Cripps, a Portsmouth Bumboat Woman) Angela Christine Smith* Sergeant of Marines Michael Connolly* ENSEMBLE OF SAILORS, FIRST LORD’S SISTERS, COUSINS, AND AUNTS Brooke Collins*, Michael Galante, Merrill Grant*, Andy Herr*, Sarah Hutchison*, Hannah Kurth*, Lance Olds*, Jennifer Piacenti*, Chris-Ian Sanchez*, Cameron Smith, Sarah Caldwell Smith*, Laura Sudduth*, and Matthew Wages* Scene: Quarterdeck of H.M.S. Pinafore *The actors and stage managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. -

Byronic Heroism Byronic Heroism Refers to a Radical and Revolutionary

Byronic Heroism Byronic heroism refers to a radical and revolutionary brand of heroics explored throughout a number of later English Romantic and Victorian works of literature, particularly in the epic narrative poems of the English Romantic poet Lord Byron, including Manfred, Don Juan, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, the Giaour, and The Corsair. The figure of the Byronic hero was among the most potent and popular character archetypes developed during the late English Romantic period. While traditional literary heroes are usually marked by their valor, intrinsic goodness, commitment to righteous political and social causes, honesty, courage, propriety, and utter selflessness, Byronic heroes are defined by rather different character traits, many of which are partially or even entirely opposed to standard definitions of heroism. Unlike most traditional heroic figures, Byronic heroes are often deeply psychologically tortured and reluctant to identify themselves, in any sense, as heroic. Byronic heroes tend to exhibit many of the following personality traits: cynicism, arrogance, absolute disrespect for authority, psychological depth, emotional moodiness, past trauma, intelligence, nihilism, dark humor, self-destructive impulses, mysteriousness, sexual attractiveness, world- weariness, hyper-sensitivity, social and intellectual sophistication, and a sense of being exiled or outcast both physically and emotionally from the larger social world. Byronic heroes can be understood as being rather akin, then, to anti-heroes (unlike Byronic heroes, though, anti-heroes tend to be rather reluctant or helpless heroes). Byronic heroes are often committed not to action on behalf of typically noble causes of “good,” but, instead, to the cause of their own self-interest, or to combatting prevailing and oppressive social and political establishments, or to particular problems or injustices in which they take a particular and often personal interest. -

Christina Rossetti

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com ChristinaRossetti MackenzieBell,HellenaTeresaMurray,JohnParkerAnderson,AgnesMilne the g1ft of Fred Newton Scott l'hl'lll'l'l'llllftlill MMM1IIIH1I Il'l'l lulling TVr-K^vr^ lit 34-3 y s ( CHRISTINA ROSSETTI J" by thtie s-ajmis atjthoe. SPRING'S IMMORTALITY: AND OTHER POEMS. Th1rd Ed1t1on, completing 1,500 copies. Cloth gilt, 3J. W. The Athen-cum.— ' Has an unquestionable charm of its own.' The Da1ly News.— 'Throughout a model of finished workmanship.' The Bookman.—' His verse leaves on us the impression that we have been in company with a poet.' CHARLES WHITEHEAD : A FORGOTTEN GENIUS. A MONOGRAPH, WITH EXTRACTS FROM WHITEHEAD'S WORKS. New Ed1t1on. With an Appreciation of Whitehead by Mr, Hall Ca1ne. Cloth, 3*. f»d. The T1mes. — * It is grange how men with a true touch of genius in them can sink out of recognition ; and this occurs very rapidly sometimes, as in the case of Charles Whitehead. Several works by this wr1ter ought not to be allowed to drop out of English literature. Mr. Mackenzie Bell's sketch may consequently be welcomed for reviving the interest in Whitehead.' The Globe.—' His monograph is carefully, neatly, and sympathetically built up.' The Pall Mall Magaz1ne.—' Mr. Mackenzie Bell's fascinating monograph.' — Mr. /. ZangwiU. PICTURES OF TRAVEL: AND OTHER POEMS. Second Thousand. Cloth, gilt top, 3*. 6d. The Queen has been graciously pleased to accept a copy of this work, and has, through her Secretary, Sir Arthur Bigge, conveyed her thanks to the Author. -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

Angeli, Helen Rossetti, Collector Angeli-Dennis Collection Ca.1803-1964 4 M of Textual Records

Helen (Rossetti) Angeli - Imogene Dennis Collection An inventory of the papers of the Rossetti family including Christina G. Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Michael Rossetti, as well as other persons who had a literary or personal connection with the Rossetti family In The Library of the University of British Columbia Special Collections Division Prepared by : George Brandak, September 1975 Jenn Roberts, June 2001 GENEOLOGICAL cw_T__O- THE ROssFTTl FAMILY Gaetano Polidori Dr . John Charlotte Frances Eliza Gabriele Rossetti Polidori Mary Lavinia Gabriele Charles Dante Rossetti Christina G. William M . Rossetti Maria Francesca (Dante Gabriel Rossetti) Rossetti Rossetti (did not marry) (did not marry) tr Elizabeth Bissal Lucy Madox Brown - Father. - Ford Madox Brown) i Brother - Oliver Madox Brown) Olive (Agresti) Helen (Angeli) Mary Arthur O l., v o-. Imogene Dennis Edward Dennis Table of Contents Collection Description . 1 Series Descriptions . .2 William Michael Rossetti . 2 Diaries . ...5 Manuscripts . .6 Financial Records . .7 Subject Files . ..7 Letters . 9 Miscellany . .15 Printed Material . 1 6 Christina Rossetti . .2 Manuscripts . .16 Letters . 16 Financial Records . .17 Interviews . ..17 Memorabilia . .17 Printed Material . 1 7 Dante Gabriel Rossetti . 2 Manuscripts . .17 Letters . 17 Notes . 24 Subject Files . .24 Documents . 25 Printed Material . 25 Miscellany . 25 Maria Francesca Rossetti . .. 2 Manuscripts . ...25 Letters . ... 26 Documents . 26 Miscellany . .... .26 Frances Mary Lavinia Rossetti . 2 Diaries . .26 Manuscripts . .26 Letters . 26 Financial Records . ..27 Memorabilia . .. 27 Miscellany . .27 Rossetti, Lucy Madox (Brown) . .2 Letters . 27 Notes . 28 Documents . 28 Rossetti, Antonio . .. 2 Letters . .. 28 Rossetti, Isabella Pietrocola (Cole) . ... 3 Letters . ... 28 Rossetti, Mary . .. 3 Letters . .. 29 Agresti, Olivia (Rossetti) . -

Journal of Stevenson Studies

1 Journal of Stevenson Studies 2 3 Editors Dr Linda Dryden Professor Roderick Watson Reader in Cultural Studies English Studies Faculty of Art & Social Sciences University of Stirling Craighouse Stirling Napier University FK9 4La Edinburgh Scotland Scotland EH10 5LG Scotland Tel: 0131 455 6128 Tel: 01786 467500 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Contributions to future issues are warmly invited and should be sent to either of the editors listed above. The text should be submitted in MS WORD files in MHRA format. All contributions are subject to review by members of the Editorial Board. Published by The Centre for Scottish Studies University of Stirling © the contributors 2005 ISSN: 1744-3857 Printed and bound in the UK by Antony Rowe Ltd. Chippenham, Wiltshire. 4 Journal of Stevenson Studies Editorial Board Professor Richard Ambrosini Professor Gordon Hirsch Universita’ de Roma Tre Department of English Rome University of Minnesota Professor Stephen Arata Professor Katherine Linehan School of English Department of English University of Virginia Oberlin College, Ohio Professor Oliver Buckton Professor Barry Menikoff School of English Department of English Florida Atlantic University University of Hawaii at Manoa Dr Jenni Calder Professor Glenda Norquay National Museum of Scotland Department of English and Cultural History Professor Richard Dury Liverpool John Moores University of Bergamo University (Consultant Editor) Professor Marshall Walker Department of English The University of Waikato, NZ 5 Contents Editorial -

Marschner Heinrich

MARSCHNER HEINRICH Compositore tedesco (Zittau, 16 agosto 1795 – Hannover, 16 dicembre 1861) 1 Annoverato fra i maggiori compositori europei della sua epoca, nonché degno rivale in campo operistico di Carl Maria von Weber, strinse amicizia con i maggiori musicisti del tempo, fra cui Ludwig van Beethoven e Felix Mendelssohn Bartoldy. Dopo gli studi fatti a Lipsia ed a Praga con Tomášek e dopo essersi introdotto nel mondo musicale viennese, fu nominato maestro di cappella a Bratislava e successivamente divenne il direttore dei teatri dell'opera di Dresda e Lipsia; fu quindi ad Hannover nel periodo 1830-59, per dirigere la cappella di corte. Marschner fu fondamentalmente un compositore teatrale, fra le opere che gli conferirono maggior fama si annoverano: Der Vampyr (1828), Der templar und die Jüdin (1829) e un'opera di gusto popolare e leggendario, come è nel suo stile, intitolata Hans Heiling (1833), la quale ha alcune analogie con L'olandese volante di Richard Wagner. Caratteristica dell'arte di Marschner sono: la ricerca (nel melodramma) di soggetti soprannaturali caratteristici di quel senso puramente romantico di "orrore dilettevole", ma anche cavallereschi e soprattutto popolari, resi attraverso una ritmica incalzante, una vasta coloritura dei timbri orchestrali e con l'ausilio di numerosi leitmotiv e fili conduttori musicali. Non mancano inoltre nella sua produzione numerosi Lieder, due quartetti per pianoforte e ben sette trii per pianoforte particolarmente apprezzati da Robert Schumann. 2 3 HANS HEILING Tipo: Opera romantica in un prologo e tre atti Soggetto: libretto di Philipp Eduard Devrient Prima: Berlino, Königliches Opernhaus, 24 maggio 1833 Cast: la regina degli spiriti (S), Hans Heiling (Bar), Anna (S), Gertrude (A), Konrad (T), Stephan (B), Niklas (rec); spiriti, contadini, invitati, giocatori, tiratori Autore: Heinrich Marschner (1795-1861) Il personaggio di Hans Heiling, tra quelli creati da Marschner, rappresenta una delle più notevoli incarnazioni del tipico tema romantico dell’io diviso, condannato a non trovare la propria unità. -

Radical Failure. the Reinvention of German Identity in the Films of Christian Schlingensief

XVI Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Departamento de Historia. Facultad Humanidades. Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Mar del Plata, 2017. Radical Failure. The Reinvention of German Identity in the Films of Christian Schlingensief. Tindemans, Klass. Cita: Tindemans, Klass (2017). Radical Failure. The Reinvention of German Identity in the Films of Christian Schlingensief. XVI Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Departamento de Historia. Facultad Humanidades. Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Mar del Plata. Dirección estable: https://www.aacademica.org/000-019/621 Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: https://www.aacademica.org. para publicar en actas Radical Failure. German Identity and (Re)unification in the Films of Christian Schlingensief. Bertolt Brecht, the German playwright, made a note about his play The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, written in 1941. The play depicts a Chicago gangster boss, clearly recognizable as a persiflage of Adolf Hitler. Brecht writes: “The big political criminals should be sacrificed, and first of all to ridicule. Because they are not big political criminals, they are perpetrators of big political crimes, which is something completely different.” (Brecht 1967, 1177). In 1997 the German filmmaker, theatre director and professional provocateur Christoph Schlingensief created the performance Mein Filz, mein Fett, mein Hase at the Documenta X – the notoriously political episode of the art manifestation in Kassel, Germany – as a tribute to Fluxus-artist Joseph Beuys.