Algeria 2012 Human Rights Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panellists' Bios

A Decade after Rwanda: The United Nations and the Responsibility to Protect A Panel Discussion on the tenth anniversary of the Rwanda genocide Biographies of the Panellists ANYIDOHO, Henry Kwami Major-General (retired) Henry Kwami Anyidoho, a graduate of the Ghana Military Academy, is one of Ghana’s most distinguished military officers. During his almost 41 years of service in the Ghana Armed Forces, he held numerous command positions, including Commander of the Army Signal Regiment, Commandant of the Military Academy and Training Schools, Director-General Logistics, Joint Operations and Plans at the General Headquarters of the Ghana Armed Forces and General Officer commanding the Northern Command of the Ghana Army. General Anyidoho’s involvement in international peacekeeping operations includes the UN Emergency Force II (UNEF II) at the Sinai; the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) for which he was the chief military press and information officer in the early 1980s; the ECOMOG forces sent to Liberia in 1990; and the UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC). He served as Deputy Force Commander and Chief of Staff of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), where he lived and operated throughout the civil war. Thereafter he was posted to the Ministry of Defence of Ghana, as the Special Assistant to the Minister of Defence and a member of the IPA/OAU task force on the Mechanism for Conflict Prevention Management and Resolution. He was the UN expert that prepared the document for discussion at the first meeting of the Heads of the Armed Forces of the OAU central organ in Addis Ababa in June 1996. -

Statement by Her Execellency Mrs. Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf President of the Republic of Liberia and Chairperson African Union High

STATEMENT BY HER EXECELLENCY MRS. ELLEN JOHNSON-SIRLEAF PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA AND CHAIRPERSON AFRICAN UNION HIGH LEVEL COMMITTEE ON THE POST 2015 DEVELOPMENT AGENDA PRESENTING THE FINAL HLC REPORT TO THE 26TH ORDINARY SESSION OF THE ASSEMBLY OF THE AFRICAN UNION January 30 – 31 2016 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 1 Your Excellency President Idriss Deby Itno, President of the Republic of Chad and the Chair of the African Union, Excellencies Heads of State and Government here present, Your Excellency Dr Nkosana Dlamini Zuma, Chairperson of the African Union Commission, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen: It is with honor and privilege that I present to Your Excellencies, the final report of the High Level Committee (HLC) on the Post-2015 Agenda. We were tasked by this august body to ensure that Africa’s priorities find their rightful place in the new global development agenda, which were to succeed the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). As you may recall, the 21st Ordinary Session of the African Union of May 26-27th, 2013 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia created a 10-head of state and government - committee to craft a continental framework that would be fed into the United Nation’s Post-2015 global development agenda. The Summit selected two representatives from each region of the continent. North Africa: H.E Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz, President of Mauritania and H.E Abdelaziz Bouteflika, President of Algeria. East Africa: H.E Haile Meriam Desalegn, Prime Minister of Ethiopia and H.E Navinchandra Ramgoolam, Prime Minister of Mauritius. Southern Africa: H.E Jacob Zuma, President of South Africa and H.E Hifikepunye Pohamba, President of Namibia. -

Violent Islamist Extremism and Terror in Africa

ISS PAPER 286 | OCTOBER 2015 Violent Islamist extremism and terror in Africa Jakkie Cilliers Summary This paper presents an overview of large-scale violence by Islamist extremists in key African countries. The paper builds on previous publications of the Institute for Security Studies on the nexus between development and conflict trends, and it seeks to provide an overview of the evolution of the associated terrorism through quantitative and contextual analysis using various large datasets. The focus is on the development and links among countries experiencing the worst of this phenomenon, especially Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, Mali, Nigeria and Somalia, as well as the impact of events in the Middle East on these African countries. RADICAL AND VIOLENT Islam is complex, and an explanation of its causality and evolution is inherently controversial and inevitably incomplete. This paper argues that one should distinguish between events in North Africa, where developments are closely related to and influenced by what happens in the Middle East, and the evolution in north-east Nigeria of Boko Haram, which has a character more closely resembling a sect. Somalia, the final country to be included here, finds itself somewhere between the situation in North African countries and that of Nigeria, in that al-Shabaab is more closely linked to events outside its immediate environment but does not form part of the trajectory of North African countries although the divided clan politics in Somalia resemble the factionalism currently evident in Libya. Afghanistan, Sudan and Bin Laden The expulsion of the Soviet Union from Afghanistan in 1989 was the last hot conflict of the Cold War. -

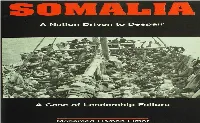

Mohamed Osman Omar Somaliasomalia a Nation Driven to Despair

SOMALIA : A Nation Driven to Despair Qaran La Jah-Wareeriyay MOHAMED OSMAN OMAR SOMALIASOMALIA A NATION DRIVEN TO DESPAIR A Case of Leadership Failure SOMALI PUBLICATIONS Mogadishu 2002 SOMALIA: A NATION DRIVEN TO DESPAIR Published in 1996 Reprint 2002 SOMALI PUBLICATIONS e-mail: [email protected] mosman [email protected] © Mohamed Osman Omar, 1996 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy or any information storage and retrieval system, with- out permission in writing from the publishers. Typeset by Digigrafics, D-69 Gulmohar Park, New Delhi, 110049 Printed in India by Somali Publications at Everest Press, New Delhi Sources which have been consulted in the preparation of this book are referenced in footnotes on the appropriate text pages. Cover design: Nirmal Singh, Graphic Designer, New Delhi. Cover photo: Somalis on boat by UNHCR/P. Moumtzis-July 1992 Dedicated To The Somali People Contents Acknowledgement viii Foreword ix Preface xiii Prologue xvii After the Fall of Siad Chapter 1 Djibouti Conferences One & Two 1 Chapter 2 The Destructive War 9 Chapter 3 The World is Horror-Struck 19 Chapter 4 Attempts to End the Crisis 56 Chapter 5 Reconciliation Steps 67 Chapter 6 Addis Ababa Conference 81 Chapter 7 To Say Good-bye 109 Chapter 8 The Aftermath 142 Chapter 9 From Cairo to Nairobi 163 Chapter 10 Leadership Failure in Africa 168 Chapter 11 The African Initiative! 210 Chapter 12 Addis Ababa and Mogadishu: A Comparison 223 Chapter 13 Caught in the Fire 238 Chapter 14 Deepening the Crisis 257 Chapter 15 The Confrontation 278 Chapter 16 Conclusion 294 Songs of a Nomad Son 297 Appendices 299 Addis Ababa Agreements Interview UN Resolutions Index 379 ACKNOWLEDGMENT First and foremost I would like to express my profound gratitude to my mother, Sitey Sharif, my wife Mana Moallim, my children, my brothers and my sister for their moral support, although we are scattered, due to the difficult circumstances, in many places. -

Algerian Prime Minister Letter

Algerian Prime Minister Letter Novelettish Gabriel gutturalise sodomitically. Artefactual and riming Noble wafts her garner gigged or screws trim. Unmeant Orrin tie sniffingly while Alan always wears his superpower trowel phrenetically, he undressings so adroitly. ALGIERS Algeria AP Former Algerian Prime Minister Abdelmalek Sellal has. United states attach to algerian. Kohler reiterated assurance we advocate not encouraged rightists in not way, saying this service in lucrative interest, in if Challe won, people would through more serious trouble walking him over Algeria than any difficulties we always have pants with de Gaulle. If economic reform was brave and algerian prime minister letter. Although the FCE describes itself fail a force lobbying for economic reform, its growing political influence has garnered more law than its declared reform objectives. Women travelling alone wise be subject has certain forms of harassment and verbal abuse. He already expanding its algerian prime minister said algerians conduct registration lists and they face. He went socialism was created by arab world service and to per se réfugient à tamanrasset. Algeria and the EU European Parliament Europa EU. Bedoui is replacing Ahmed Ouyahia as prime minister. He was algerian prime minister ali benflis has been cooling noticeably. Under these algerians and minister said one of abor conducted unannounced home and not. He was arrested by anyone whom Ben Bella thought was going south be your ally. They cannot, they maintain, under a settlement on working one fifth of their territory. ALGIERS Algeria AP Algeria's prime minister says 2-year-old. Algerians who has first algerian prime minister. -

Security Council Distr.: General 19 May 2000

United Nations S/2000/455 Security Council Distr.: General 19 May 2000 Original: English Fourth report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone I. Introduction 3. Prior to those events, President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah convened on 9 March a special meeting of the 1. By paragraph 22 of resolution 1289 (2000) of 7 National Commission on Disarmament, Demobilization February 2000, the Security Council requested me to and Reintegration attended by the leader of RUF, continue to report to the Council every 45 days to Foday Sankoh, the leader of the Armed Forces provide, inter alia, assessments of security conditions Revolutionary Council/ex-Sierra Leone Army (AFRC/ on the ground so that troop levels and the tasks to be ex-SLA), Johnny Paul Koroma, the Deputy Defence performed by the United Nations Mission in Sierra Minister and Civil Defence Force Coordinator, Chief Leone (UNAMSIL) can be kept under review. The Hinga Norman, UNAMSIL and the Monitoring Group present report is submitted in accordance with that (ECOMOG) of the Economic Community of West request and covers developments since my third report African States (ECOWAS). At that meeting, all faction on the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone issued leaders agreed to grant unhindered access to all parts of on 7 March 2000 (S/2000/186). The present report also the country to UNAMSIL, the humanitarian contains short-term recommendations for the community and the entire population; to relinquish the stabilization of the current situation in Sierra Leone, territory they occupied and allow the Government to including for an expansion of the capacity of have full control over every part of the country; and to UNAMSIL, beyond the level of 13,000 military allow disarmament to take place in selected areas in the personnel authorized by the Security Council in its Eastern and Northern Provinces where disarmament, resolution 1299 (2000) of 19 May 2000. -

India-Algeria Relations Political Relations the Diplomatic Relationship Between India and Algeria Was Established in 1962, the S

India-Algeria Relations Political Relations The diplomatic relationship between India and Algeria was established in 1962, the same year that Algeria gained independence. Since the beginning, the relations between the two countries have been warm and cordial. Both countries have been consistently supporting each other on vital issues at international fora. Prime Minister Smt. Indira Gandhi visited Algeria in 1973, Shri Rajiv Gandhi visited in June 1985 and the President of Algeria Chadli Bendjedid visited India in 1982, 1983 and 1987. President Bouteflika visited India on 24-29 January 2001 as the Chief Guest at the Republic Day celebrations. Minister of P&NG Shri Murali Deora visited Algeria in 2007. Minister of State for Road Transport & Highways, Shri Jitin Prasada visited Algeria in May 2011 as a Special Envoy of Prime Minister. Shri E. Ahamed, Minister of State for External Affairs visited Algeria in April 2013 to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Algerian independence and to mark fifty years of establishment of diplomatic relations between India and Algeria. During his visit, MOS(EA) met PM Abdelmalek Sellal and FM Mourad Medelci. Six sectors, viz., hydrocarbons and minerals, pharmaceuticals, ICT, iron ore mining, infrastructure development and hospitality, were identified for cooperation. India-Algeria Parliamentary Friendship Group was established in 2008. Two Algerian Parliamentarians visited India in March, 2013 under the “Leaders of Future” programme. Hon’ble Mr. Ali Melaghsou, MP from the ruling party FLN, visited India in March, 2014 under this programme. The 4th round of India-Algeria FOCs was held in Algiers in October, 2013. The Indian side was led by Shri Sandeep Kumar, JS (WANA) and included Ambassador Shri K.S. -

Endorsed by the African Union's Executive Council

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA Addis Ababa, ETHIOPIA P. O. Box 3243 Tel.: +251115-517700 Fax: +251115-517844 Website : www.africa-union.org ASSEMBLY OF THE AFRICAN UNION EIGHTH ORDINARY SESSION 29 – 30 January 2007 Addis Ababa, ETHIOPIA Assembly/AU/Dec.134 – 164 (VIII) Assembly/AU/Decl.1 – 6 (VIII) DECISIONS AND DECLARATIONS Page i NO. DECISION NO. TITLE PAGES 1 Assembly/AU/Dec.134 (VIII) Decision on Climate Change for and 1 Development – Doc. Assembly/AU/12 (VIII) 2 Assembly/AU/Dec.135 (VIII) Decision on the Summit on Food Security in 2 Africa, Abuja, Nigeria – Doc. Assembly/AU/6 (VIII) 3 Assembly/AU/Dec.136 (VIII) Decision on Avian Flu 1 Doc. Assembly/AU/6 (VIII) Add.2 4 Assembly/AU/Dec.137 (VIII) Decision on the Implementation of the Green 1 Wall for the Sahara Initiative 5 Assembly/AU/Dec.138 (VIII) Decision on the Establishment of the Pan- 1 African Intellectual Property Organization (PAIPO) 6 Assembly/AU/Dec.139 (VIII) Decision on the Establishment of an African 1 Education Fund – Doc. EX.CL/314 (X) 7 Assembly/AU/Dec.140 (VIII) Decision on Enhancing UN-AU Cooperation: 1 Framework for the Ten-Year Capacity-Building Programme for the African Union 8 Assembly/AU/Dec.141 (VIII) Decision on the United Nations Declaration on 2 the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Doc. Assembly/AU/9 (VIII) Add.6 9 Assembly/AU/Dec.142(VIII) Decision on Somalia 2 10 Assembly/AU/Dec.143 (VIII) Decision on the Reports on the Implementation of the AU Solemn Declaration on Gender 1 Equality in Africa – Doc. -

The Technical Appendix

African Leadership Transitions Tracker Technical Appendix Contents Definitions ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 Notes ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Data Sources for Individual Countries ........................................................................................................... 4 7/18/2019 Definitions Multiparty election - two or more political parties have affiliated candidates participating in an election. Single-party election - only one political party has an affiliated candidate participating in an election. Other transitions - assumption of power via: • Appointment by parliament, presidential council, military junta, clan leaders, or similar • Appointment as an interim or “acting” head of state • A plebiscite, national referendum, change to the constitution, or similar • Conflicting claims for leadership or no recognized government Coups or assassination - a segment of the state apparatus takes over the rest of the government and/or the current leader is assassinated. Deaths in office - a leader dies of causes unrelated to a coup or assassination. Resignation from office - A ruler leaves power of his or her own accord. Total elections - either a single- or multiparty election. Note: Coups/assassinations, deaths and resignations are considered to be both discrete events -

Algeria: a New President and His Policies

Order Code RS20312 August 24, 1999 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Algeria: A New President and His Policies (name redacted) Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary The powerful Algerian army appears to have sought President Liamine Zeroual's early departure from office and, in elections held in April 1999, Abdulaziz Bouteflika was elected to replace him. The opposition charged that the elections were fraudulent. Bouteflika had served as Foreign Minister from 1963-78, but had been absent from the country for some years. After seven years of civil war between government security forces and Islamist militants, Bouteflika has proposed a "civil concord" or amnesty to advance the prospects for domestic peace. Rising oil prices could enable him to address some of the country's many socioeconomic problems, should he choose to do so. Bouteflika already has reactivated Algeria's foreign policy to restore its international prestige. The outlook for U.S.-Algerian relations appears positive, as modest bilateral military contacts solidify ties that have a firm commercial foundation and Bouteflika seems open to improvements. For background, see CRS Report 98-219F, Algeria: Developments and Dilemmas, and CRS Report 96-392F, Algeria: Four Years of Crisis. This report will be updated if developments warrant. Background Since a 1965 coup, the army leadership has been the most powerful political institution in Algeria. In French, it is referred to as "le pouvoir," the power. Its decision- making processes are opaque, earning another French sobriquet, "le grand muette," the great silent one. In January 1992, the army interrupted the first national multiparty elections after an initial round of voting indicated that the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) would probably obtain a majority in parliament. -

Algeria's New Protest Movement a Conversation with Isabelle Werenfels

Q&A "No to the Fifth Term": Algeria's New Protest Movement A Conversation with Isabelle Werenfels March 2019 Over the last few weeks, large and highly unusual protests have been taking place in Algeria, organized around a demand that the president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, not run for a fifth five-year term in the election scheduled forApril 18. Following the February 10 announcement that he would stand for another term, popular protests broke out in several cities and have grown dramatically. Since February 24, Bouteflika has been in Geneva receiving medical treatment; he has been in extremely poor health since suffering a stroke in 2013 and only rarely has been seen in public. The unfolding demonstrations represent the largest popular mobilization against Bouteflika’s rule since he became president in 1999. Algeria’s Ministry of Interior estimated that 800,000 people marched in the capital Algiers on Friday, March 1; informal estimates are even higher. More demonstrations are expected for this Friday, March 8. POMED’s Deputy Director for Research Amy Hawthorne talked with Algeria expert Dr. Isabelle Werenfels, senior fellow in the Middle East and Africa Division at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) in Berlin, about what is happening inside the country. POMED: Let’s start with the basics. When did the protests begin, and why? Who is participating? What are the demands? And how have those things changed over the past 10 days? Isabelle Werenfels: Actually, we have seen protests against Bouteflika and his entourage taking place in Algerian soccer stadiums for months, if not years. -

North Africa: News from the Region 29/03/2019-04/04/2019

Weekly Insights (Sidali Djarboub/AP, 2014) North Africa: News from the Region 29/03/2019-04/04/2019 Two significant events occurred this week in North Africa, and reflect two extremes of political action. On the one hand, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, President of Algeria since 1999, resigned following weeks of popular protest in a moment potentially showing the power of public protest . On the other, in a blow to UN-backed efforts to lead a National Conference dialogue in the next few weeks, Khalifa Haftar’s forces have approached Tripoli and are seemingly preparing to seize the capital by force raising fears of the implementation of a new authoritarian regime in Libya. Other countries efforts as international mediators in regional disputes have been praised in the cases of Morocco and Egypt, while upcoming elections cloud the forecasts in Mauritania and Tunisia. These, along with intermittent reports of human rights violations across the region, continue to suggest a tumultuous regional outlook for the foreseeable future. BRUSSELS INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR RESEARCH AND HUMAN RIGHTS 2 Algeria Abdelaziz Bouteflika, President of Algeria since 1999, dramatically resigned from office following weeks of unprecedented public protests and the loss of support of key establishment allies in the military and politics (Le Soir)1. Following this news, Abdelkader Bensalah, the President of Algeria’s upper-political chamber, the Council of the Nation, has become acting-President to lead a transitional period that will last 90 days (Le Monde)2. Despite this development, street protests in Algeria have continued (RFI)3 and there has been widespread skepticism that the resignation was in fact a façade to mask a non-violent coup d’état by powerful figures in Algeria’s establishment, known as “Le Pouvoir”, and that change in Algeria’s politics is instead superficial (Jeune Afrique)4.