Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A STAR SPANGLED OFFICERS Harvey Lichtenstein President and Chief Executive Officer SALUTE to BROOKLYN Judith E

L(30 '11 II. BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC BOARD OF TRUSTEES Hon. Edward I. Koch, Hon. Howard Golden, Seth Faison, Paul Lepercq, Honorary Chairmen; Neil D. Chrisman, Chairman; Rita Hillman, I. Stanley Kriegel, Ame Vennema, Franklin R. Weissberg, Vice Chairmen; Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Chief Executive Officer; Harry W. Albright, Jr., Henry Bing, Jr., Warren B. Coburn, Charles M. Diker, Jeffrey K. Endervelt, Mallory Factor, Harold L. Fisher, Leonard Garment, Elisabeth Gotbaum, Judah Gribetz, Sidney Kantor, Eugene H. Luntey, Hamish Maxwell, Evelyn Ortner, John R. Price, Jr., Richard M. Rosan, Mrs. Marion Scotto, William Tobey, Curtis A. Wood, John E. Zuccotti; Hon. Henry Geldzahler, Member ex-officio. A STAR SPANGLED OFFICERS Harvey Lichtenstein President and Chief Executive Officer SALUTE TO BROOKLYN Judith E. Daykin Executive Vice President and General Manager Richard Balzano Vice President and Treasurer Karen Brooks Hopkins Vice President for Planning and Development IN HONOR OF THE 100th ANNIVERSARY Micheal House Vice President for Marketing and Promotion ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE STAFF OF THE Ruth Goldblatt Assistant to President Sally Morgan Assistant to General Manager David Perry Mail Clerk BROOKLYN BRIDGE FINANCE Perry Singer Accountant Tuesday, November 30, 1982 Jack C. Nulsen Business Manager Pearl Light Payroll Manager MARKETING AND PROMOTION Marketing Nancy Rossell Assistant to Vice President Susan Levy Director of Audience Development Jerrilyn Brown Executive Assistant Jon Crow Graphics Margo Abbruscato Information Resource Coordinator Press Ellen Lampert General Press Representative Susan Hood Spier Associate Press Representative Diana Robinson Press Assistant PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT Jacques Brunswick Director of Membership Denis Azaro Development Officer Philip Bither Development Officer Sharon Lea Lee Office Manager Aaron Frazier Administrative Assistant MANAGEMENT INFORMATION Jack L. -

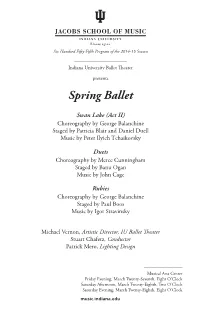

Spring Ballet

Six Hundred Fifty-Fifth Program of the 2014-15 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents Spring Ballet Swan Lake (Act II) Choreography by George Balanchine Staged by Patricia Blair and Daniel Duell Music by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Duets Choreography by Merce Cunningham Staged by Banu Ogan Music by John Cage Rubies Choreography by George Balanchine Staged by Paul Boos Music by Igor Stravinsky Michael Vernon, Artistic Director, IU Ballet Theater Stuart Chafetz, Conductor Patrick Mero, Lighting Design _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, March Twenty-Seventh, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, March Twenty-Eighth, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, March Twenty-Eighth, Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu Swan Lake (Act II) Choreography by George Balanchine* ©The George Balanchine Trust Music by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Original Scenery and Costumes by Rouben Ter-Arutunian Premiere: November 20, 1951 | New York City Ballet City Center of Music and Drama Staged by Patricia Blair and Daniel Duell Stuart Chafetz, Conductor Violette Verdy, Principal Coach Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Odette, Queen of the Swans Raffaella Stroik (3/27) Elizabeth Edwards (3/28 mat ) Natalie Nguyen (3/28 eve ) Prince Siegfried Matthew Rusk (3/27) Colin Ellis (3/28 mat ) Andrew Copeland (3/28 eve ) Swans Bianca Allanic, Mackenzie Allen, Margaret Andriani, Caroline Atwell, Morgan Buchart, Colleen Buckley, Danielle Cesanek, Leah Gaston (3/28), Bethany Green (3/28 eve ), Rebecca Green, Cara Hansvick -

DOCTORAL THESIS the Dancer's Contribution: Performing Plotless

DOCTORAL THESIS The Dancer's Contribution: Performing Plotless Choreography in the Leotard Ballets of George Balanchine and William Forsythe Tomic-Vajagic, Tamara Award date: 2013 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 THE DANCER’S CONTRIBUTION: PERFORMING PLOTLESS CHOREOGRAPHY IN THE LEOTARD BALLETS OF GEORGE BALANCHINE AND WILLIAM FORSYTHE BY TAMARA TOMIC-VAJAGIC A THESIS IS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF DANCE UNIVERSITY OF ROEHAMPTON 2012 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the contributions of dancers in performances of selected roles in the ballet repertoires of George Balanchine and William Forsythe. The research focuses on “leotard ballets”, which are viewed as a distinct sub-genre of plotless dance. The investigation centres on four paradigmatic ballets: Balanchine’s The Four Temperaments (1951/1946) and Agon (1957); Forsythe’s Steptext (1985) and the second detail (1991). -

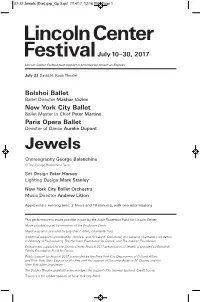

Gp 3.Qxt 7/14/17 12:16 PM Page 1

07-22 Jewels (Eve).qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/14/17 12:16 PM Page 1 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 22 David H. Koch Theater Bolshoi Ballet Ballet Director Makhar Vaziev New York City Ballet Ballet Master in Chief Peter Martins Paris Opera Ballet Director of Dance Aurélie Dupont Jewels Choreography George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust Set Design Peter Harvey Lighting Design Mark Stanley New York City Ballet Orchestra Music Director Andrew Litton Approximate running time: 2 hours and 10 minutes, with two intermissions This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Made possible in part by members of the Producers Circle Major support is provided by LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust. Additional support is provided by Jennie L. and Richard K. DeScherer, the Lepercq Charitable Foundation in Memory of Paul Lepercq, The Harkness Foundation for Dance, and The Joelson Foundation. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2017 presentation of Jewels is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. Public support for Festival 2017 is provided by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. The Bolshoi Theatre gratefully acknowledges the support of its General Sponsor, Credit Suisse. Travelers is the Global Sponsor of New York City Ballet. 07-22 Jewels (Eve).qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/14/17 12:16 PM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2017 JEWELS July 22, 2017, at 7:30 p.m. -

Paul Boos on Jewels

Spring 2018 Ballet Review From the Spring 2018 issue of Ballet Review Paul Boos on “Jewels” Cover photograph by Stephanie Berger, Lincoln Center Festival: Dorothée Gilbert and Hugo Marchand in Emeralds. © 2018 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 8 Tanglewood – Jay Rogoff 10 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 12 New York – Susanna Sloat 15 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 17 Moscow/St. Petersburg – Susanna Sloat 23 Saratoga Springs – Jay Rogoff 26 Jacob’s Pillow – Ian Spencer Bell 28 Toronto – Gary Smith 30 Sun Valley – Susanna Sloat 33 Stuttgart – Gary Smith 79 34 New York – Harris Green 36 New York – Juan Michael Porter II 37 Philadelphia – Eva Shan Chou Ballet Review 46.1 38 Brooklyn – Joseph Houseal Spring 2018 39 Miami – Michael Langlois Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino John Morrone 40 A Conversation with Steven McRae Managing Editor: Roberta Hellman George Dorris Senior Editor: 60 46 Picasso in Italy Don Daniels Associate Editors: 48 Adolf de Meyer: Joel Lobenthal Quicksilver Brilliance Larry Kaplan Alice Helpern 52 From the Horse’s Mouth Webmaster: Curated by Rajika Puri David S. Weiss Selected & Edited by Karen Greenspan Copy Editor: Naomi Mindlin Larry Kaplan Photographers: 60 Paul Boos on Jewels Tom Brazil 40 Costas Gary Smith 75 Demis Volpi Associates: Peter Anastos Robert Greskovic John Goodman George Jackson 79 André Levinson on Balanchine, Elizabeth Kendall 1925–1933 Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds 123 London Reporter – Clement Crisp James Sutton 127 Music on Disc – George Dorris David Vaughan† Edward Willinger 8 131 Check It Out Sarah C. Woodcock Cover photograph by Stephanie Berger, Lincoln Center Festival: Dorothée Gilbert and Hugo Marchand in Emeralds. -

NEWS from the JEROME ROBBINS FOUNDATION VOL. 7, NO. 1 (2020) 75Th Anniversary Gala of New York Public Library for the Performing Arts’ Jerome Robbins Dance Division

NEWS FROM THE JEROME ROBBINS FOUNDATION VOL. 7, NO. 1 (2020) 75th Anniversary Gala of New York Public Library for the Performing Arts’ Jerome Robbins Dance Division On Wednesday, December 4, 2019, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts celebrated the Jerome Robbins Dance Division’s 75th anniversary with a unique gala that raised more than $723,000 in critical funds that will help the division document, collect, and preserve the history of dance and provide free services and programs for all. More than 200 dance-loving attendees moved through the Library for the Performing Arts in Lincoln Center viewing site-specific movement pieces cre- ated specifically for the occasion by Ephrat Asherie, The Bang Group, Jean Butler, Adrian Danchig-Waring, Heidi Latsky, Michelle Manzanales, Rajika Puri, and Pam Tanowitz. Staged in unexpected spaces (among the stacks, on reading room tables, through hallways, and on stairways), these brief performances fea- tured dancers including Chelsea Ainsworth, Chris Bloom, Jason Collins, Shelby Colona, Lindsey Jones, Jeffrey Kazin, Victor Lozano, Aishwarya Madhav, Georgina Pazcoguin, Nic Petry, Jaclyn Rea, Tommy Seibold, Amber Sloan, Gretchen Smith, Leslie Taub, Melissa Toogood, and Peter Trojic. The evening’s performances culminated in the Library’s Bruno Walter Auditorium with an excerpt from Jerome Robbins’ Other Dances, featuring American Ballet Theatre Principal Dancer Sarah Lane and New York City Ballet Principal Dancer Gonzalo Garcia. Jerome Robbins originally created the work in 1976 for a fundraiser to support the Library. The Jerome Robbins Dance Division’s 75th Anniversary Gala was chaired by Caroline Cronson & The Jerome Robbins Foundation. -

Dancing the Cold War an International Symposium

Dancing the Cold War An International Symposium Sponsored by the Barnard College Dance Department and the Harriman Institute, Columbia University Organized by Lynn Garafola February 16-18, 2017 tContents Lynn Garafola Introduction 4 Naima Prevots Dance as an Ideological Weapon 10 Eva Shan Chou Soviet Ballet in Chinese Cultural Policy, 1950s 12 Stacey Prickett “Taking America’s Story to the World” Ballets: U.S.A. during the Cold War 23 Stephanie Gonçalves Dien-Bien-Phu, Ballet, and Politics: The First Sovviet Ballet Tour in Paris, May 1954 24 Harlow Robinson Hurok and Gosconcert 25 Janice Ross Outcast as Patriot: Leonid Yakobson’s Spartacus and the Bolshoi’s 1962 American Tour 37 Tim Scholl Traces: What Cultural Exchange Left Behind 45 Julia Foulkes West and East Side Stories: A Musical in the Cold War 48 Victoria Phillips Cold War Modernist Missionary: Martha Graham Takes Joan of Arc and Catherine of Siena “Behind the Iron Curtain” 65 Joanna Dee Das Dance and Decolonization: African-American Choreographers in Africa during the Cold War 65 Elizabeth Schwall Azari Plisetski and the Spectacle of Cuban-Soviet Exchanges, 1963-73 72 Sergei Zhuk The Disco Effect in Cold-War Ukraine 78 Video Coverage of Sessions on Saturday, February 18 Lynn Garafola’s Introduction Dancers’ Roundatble 1-2 The End of the Cold War and Historical Memory 1-2 Alexei Ratmansky on his Recreations of Soviet-Era Works can be accessed by following this link. Introduction Lynn Garafola Thank you, Kim, for that wonderfully concise In the Cold War struggle for hearts and minds, – and incisive – overview, the perfect start to a people outside the corridors of power played a symposium that seeks to explore the role of dance huge part. -

Robert Joffrey and Gerald Arpino's Uniquely American Vision of Dance

Monday, March 5 at 7:30pm, 2007 UMass Amherst Fine Arts Center Concert Hall GERALD ARPINO Artistic Director ROBERT JOFFREY and GERALD ARPINO Founders Artists of the Company Heather Aagard - Matthew Adamczyk - Derrick Agnoletti Fabrice Calmels - April Daly - Jonathan Dummar - Erica Lynette Edwards John Gluckman - David Gombert - Jennifer Goodman - Elizabeth Hansen William Hillard - Anastacia Holden - Victoria Jaiani - Stacy Joy Keller Julianne Kepley - Calvin Kitten - Britta Lazenga - Michael Levine - Suzanne Lopez Brian McSween - Thomas Nicholas - Emily Patterson - Eduardo Permuy Alexis Polito - Megan Quiroz - Valerie Robin - Christine Rocas - Aaron Rogers Willy Shives - Tian Shuai - Abigail Simon - Patrick Simoniello - Michael Smith Lauren Stewart - Temur Suluashvili - Kathleen Thielhelm - Mauro Villanueva Allison Walsh - Maia Wilkins - Joanna Wozniak Arpino Apprentices Brandon Alexander - Kimberly Bleich - Matthew Frain Justine Humenansky - Vicente Martinez - Erin McAfee Caitlin Meighan - Scott Spivey Cameron Basden, Adam Sklute Associate Artistic Directors Denise Olivieri Stage Manager Charthel Arthur, Mark Goldweber Ballet Masters Leslie B. Dunner Music Director & Principal Conductor Willy Shives Assistant Ballet Master Paul Lewis Music Administrator & Company Pianist Katherine Selig Principal Stage Manager Sponsored by Easthampton Savings Bank, Realty World Sawicki and WFCR 88.5FM PROGRAM Apollo Choreography by George Balanchine* Music by Igor Stravinsky** Costumes by Kathryn Bennett, after the original Karinska designs Lighting Design by Kevin Dreyer Staged by Paul Boos Balanchine’s Apollo begins with Leto, a mortal, giving birth to the god Apollo. He appears fully grown. Handmaidens unwrap him from his swaddling clothes and bring him his lute. Three muses enter and dance with him. Apollo presents each muse with the emblem of her art: a scroll to Calliope, the Muse of Poetry; a mask symbolizing the silence and power of gesture to Polyhymnia, the Muse of Mime; and a lyre to Terpsichore, the Muse of Dance and Song. -

Newsletter Fall Updates

Newsletter Fall Updates News from Jane D’Angelo Upcoming OhioDance Partnership Events: Executive Director October 12, 2019, 9:00AM – 3:00PM Dear OhioDance members, Neighborhood Best Practice Conference, City of Columbus OhioDance would like to thank and acknowl- held at the Downtown High School edge members of the OhioDance Board of 364 S. Fourth St., Columbus OH Fall News 2019 Trustees who are ending their terms, Vol 43, no. 1 Alfred Dove, Suzan Bradford Kounta, Sarah September 28, October 12, 2019 Morrison, and Kim Popa, We thank them for Dublin Arts Council - Art and Wellness the time served. Discover Series https://dublinarts.org New members to the Board of Trustees include: Angelica Bell, Adjunct Faculty, Ohio October 13, 2019, 6-7:30pm University/The Ohio State University, Artistic Two Dollar Radio Director of Factory Street Studio, Athens; 1124 Parsons Ave. Columbus OH 43206 Parris Hobbs, Branch Manager, Chase Bank, 614-725-1505 Dayton; Gregory King, Assistant Professor of Panel discussion on Labanotation, folk dance at Kent State University, and Artis- dances, and ethnic identity that preserves tic Director of the Kent Dance Ensemble; the heritages of immigrants who live in the Kristina Scales, ADA/504 & Title VI Special- Slovenian Diaspora. ist in the Division of Opportunity, Diversity Rebeka Kunej, Research Fellow in the In- and Inclusion for the Ohio Department of stitute of Ethnomusicology at the Research Transportation (ODOT), Columbus and Emily Centre of the Slovenia Academy of Sciences INSIDE Stamas, CareSource, Senior -

Season 5 with 'Momentum: International Masters'

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 20, 2015 Contact: Erika Overturff, (402) 541-6946 Full-resolution photos available at this link BALLET NEBRASKA WRAPS UP SEASON 5 WITH 'MOMENTUM: INTERNATIONAL MASTERS' OMAHA -- Three very different masterpieces spanning centuries and continents -- plus an audience favorite with a food theme -- will be on the program May 1 and 3 when Ballet Nebraska closes out its fifth season with Momentum: International Masters. “Momentum is all about showing a variety of works, and the International Masters program is an exceptional example of that," said Erika Overturff, Ballet Nebraska's founder and artistic director. "The three choreographers we're highlighting are groundbreakers and trend-setters, and their works demonstrate the range of what dance can do." Those works are: Paquita -- Originally created in 1846 for the Paris Opera Ballet, Paquita received an extensive makeover in 1881, when 19th-century master choreographer Marius Petipa restaged it for Russia's Imperial Ballet of St. Petersburg. Petipa, a Frenchman, supplemented the original ballet with sparkling dances set to music written to Petipa's specifications by Ludwig Minkus. Though the original ballet is rarely performed, these 1881 additions were such brilliant examples of Imperial Russian style that they thrived and form the Paquita we see today. "This is a quintessential tutu ballet," Overturff said. "It is a technical showpiece -- very stylish and full of energy -- and audiences love seeing it." Valse Fantaisie -- This 1967 work by the legendary 20th-century choreographer George Balanchine is set to a lively waltz by Mikhail Glinka. The ballerinas, attended by a male dancer, move together in a whirl of perpetual motion. -

Classic Balanchine

Classic Balanchine May 17–Jun 9, 2018 Program Background Prodigal Son Music: Sergei Prokofiev, Le Fils Prodigue, Op. 46 Choreography: George Balanchine Staging: Elyse Borne Scenic and Costume Design: Georges Rouault Lighting Design: John Cuff World Premiere: May 21, 1929, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt, Paris Boston Ballet Premiere: Feb 7, 1966 Stravinsky Violin Concerto Music: Igor Stravinsky, Violin Concerto in D major Choreography: George Balanchine Staging: Paul Boos, Colleen Neary Lighting Design: John Cuff World Premiere: Jun 18, 1972, New York City Ballet, New York Boston Ballet Premiere: May 5, 2017, Boston Opera House, Boston, Massachusetts Chaconne Music: Christoph Willibald von Gluck, from the opera Orfeo ed Euridice Choreography: George Balanchine Staging: Diana White Costume Design: Barbara Karinska Lighting Design: John Cuff World Premiere: Jan 22, 1977, New York City Ballet, New York Boston Ballet Premiere: May 17, 2018, Boston Opera House, Boston, Massachusetts BIO: George Balanchine Choreographer Born in St. Petersburg, Russia, George Balanchine (1904–1983) is regarded as the foremost contemporary choreographer in the world of ballet. He came to the United States in late 1933 at the age of 29, accepting the invitation of the young American arts patron Lincoln Kirstein (1907–96), whose great passions included the dream of creating a ballet company in America. At Balanchine’s behest, Kirstein was also prepared to support the formation of an American academy of ballet that would eventually rival the long-established schools of Europe. This was the School of American Ballet, founded in 1934, the first product of the Balanchine–Kirstein collaboration. Several ballet companies directed by the two were created and dissolved in the years that followed, while Balanchine found other outlets for his choreography. -

Toni Renee Taylor

Toni Renee Taylor Artist of the Creative & Performing Arts Heyman Profile https://www.heymantalent.com/t/toni-renee-taylor Laura VonHolle [email protected] Brittany Kirby [email protected] Birth Date- 06/10/1997 // U.S. Citizen (Updated Passport) Height- 5’4” Weight- 110 lbs. Hair- Strawberry-Blonde Eyes- Blue Acting Professional Representations/ Associations: Heyman Talent Agency (2020 – Present) /// Katalyst Talent Agency (Youth - 2013) /// SAG-AFTRA Member (Youth - 2013) Music Videos: Suave – SYHTF (Official Music Video) (2021) Directed and Produced by Suave & Spencer Kolssak - Shot by: Spencer Kolssak – Second Camera: William Story Choreographed by: TRTCreations (Toni Renee Taylor) – Dancers: Suave & Toni Renee Taylor (TRTCreations) Drama & Musical Theatre Performing Experience: St. Petersburg Opera Company’s Production of, Franz Lehar’s “The Merry Widow.” (2019) Role: Principal Act 3 Grissette, Frou- Frou/ Act 1&2 Ensemble (Dancer, Singer, Actress) English version by Ted & Deena Puffer. Director: Mark Sforzini, Stage Director: Adam Ciaffori, Choreographer: Daryl Gray, Chorus Master: Wayne Hobbs Cincinnati's School for Creative & Performing Arts (2007-2013) "Brigadoon" Directed and Staged by, Gina Kleesattle. Role: Dance Corps. (2011) "The Trial of the Big Bad Wolf" Directed and Staged by, Joe Caesar. Role: Cinderella. (2010) "Frog and Toad" Directed and Staged by, Gina Kleesattle. Role: Squirrel. (2009) "Charlotte's Webb" Directed and Staged by Regina Pugh. Role: Templeton. (2008) Television Experience: MTV's "Taking the Stage"