DOCTORAL THESIS the Dancer's Contribution: Performing Plotless

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class Descriptions

The Academy of Dance Arts 1524 Centre Circle Downers Grove, Illinois 60515 (630) 495-4940 Email: [email protected] Web Site: www.theacademyofdanceartshome.com DESCRIPTION OF CLASSES All Class Days and Times can be found on the Academy Class Schedule ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ BALLET PROGRAM AND TECHNIQUE CLASSES Ballet is the oldest formal and structured form of dance given the reverence of being the foundation of ALL The Dance Arts. Dancers build proper technical skills, core strength and aplomb, correct posture and usage of arms, head and foremost understand the basics in technique. Students studying Ballet progress in technique for body alignment, pirouettes, jumps, co-ordination skills, and core strength. Weekly classes are held at each level with recommendations for proper advancement and development of skills for each level. Pre-Ballet Beginning at age 5 to 6 years. Students begin the rudiments of basic Ballet Barre work. Focus is on the positions of the feet, basic Port de bras (carriage of the arms), body alignment, and simple basic steps to develop coordination skills and musicality. All this is accomplished in a fun and nurturing environment. Level A Beginning at age 6 to 8 years. Slowly the demanding and regimented nature of true classical Ballet is introduced at this level with ballet barre exercises and age/skill level appropriate center work per Academy Syllabus. When Students are ready to advance to the next level, another Level-A Ballet or B-Ballet class will be recommended per instructor. Level B Two weekly classes are required as the technical skills increase and further steps at the Barre and Center Work and introduced. -

Valerie Roche ARAD Director Momix and the Omaha Ballet

Celebrating 50 years of Dance The lights go down.The orchestra begins to play. Dancers appear and there’s magic on the stage. The Omaha Academy of Ballet, a dream by its founders for a school and a civic ballet company for Omaha, was realized by the gift of two remarkable people: Valerie Roche ARAD director of the school and the late Lee Lubbers S.J., of Creighton University. Lubbers served as Board President and production manager, while Roche choreographed, rehearsed and directed the students during their performances. The dream to have a ballet company for the city of Omaha had begun. Lubbers also hired Roche later that year to teach dance at the university. This decision helped establish the creation of a Fine and Performing Arts Department at Creighton. The Academy has thrived for 50 years, thanks to hundreds of volunteers, donors, instructors, parents and above all the students. Over the decades, the Academy has trained many dancers who have gone on to become members of professional dance companies such as: the American Ballet Theatre, Los Angeles Ballet, Houston Ballet, National Ballet, Dance Theatre of Harlem, San Francisco Ballet, Minnesota Dance Theatre, Denver Ballet, Momix and the Omaha Ballet. Our dancers have also reached beyond the United States to join: The Royal Winnipeg in Canada and the Frankfurt Ballet in Germany. OMAHA WORLD HERALD WORLD OMAHA 01 studying the work of August Birth of a Dream. Bournonville. At Creighton she adopted the syllabi of the Imperial Society for Teachers The Omaha Regional Ballet In 1971 with a grant and until her retirement in 2002. -

The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’S Split Sides

Spring 2012 Ball et Review The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’s Split Sides . © 2012 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Moscow – Clement Crisp 5 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 6 Oslo – Peter Sparling 9 Washington, D. C. – George Jackson 10 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 12 Toronto – Gary Smith 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 Toronto – Gary Smith 17 New York – George Jackson Ian Spencer Bell 31 18 The Caramel Variations Darrell Wilkins 31 Malakhov’s La Péri Francis Mason 38 Armgard von Bardeleben on Graham Don Daniels 41 The Iron Shoe Joel Lobenthal 64 46 A Conversation with Nicolai Hansen Ballet Review 40.1 Leigh Witchel Spring 2012 51 A Parisian Spring Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Francis Mason Managing Editor: 55 Erick Hawkins on Graham Roberta Hellman Joseph Houseal Senior Editor: 59 The Ecstatic Flight of Lin Hwa-min Don Daniels Associate Editor: Emily Hite Joel Lobenthal 64 Yvonne Mounsey: Encounters with Mr B 46 Associate Editor: Nicole Dekle Collins Larry Kaplan 71 Psyché and Phèdre Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Sandra Genter Photographers: 74 Next Wave Tom Brazil Costas 82 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 89 More Balanchine Variations – Jay Rogoff Associates: Peter Anastos 90 Pina – Jeffrey Gantz Robert Gres kovic 92 Body of a Dancer – Jay Rogoff George Jackson 93 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 71 100 Check It Out Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener Sarah C. -

A Mixed Blessing at the Ballet 01

Daily Telegraph July 28 2001 A mixed blessing at the ballet Photo Sheila Rock As Anthony Dowell leaves the Royal Ballet, dance critic Ismene Brown assesses his 15-year regime as director - and stars pay tribute below AT THE Royal Ballet the countdown has begun to the end of an era. A week tonight, amid flowers, Champagne and tears, Sir Anthony Dowell, the longest-serving ballet director since the company’s founder, Ninette de Valois, will end his 15-year regime. He was undoubtedly one of the great world stars of dancing, and the “Celebration Programme” will mark his achievements as such. But about his success as director of the company, opinion is far from unanimous. What makes a good director? The question has never been more of a poser than during Dowell\s captaincy of the ballet, in the most turbulent years of the Royal Opera House’s history. There are many pluses on Dowell’s account sheet - his maintenance of high classical technical standards, his welcoming of key foreign artists into the Royal (particularly Sylvie Guillem and Irek Mukhamedov), his inspiring coaching, to which leading guest stars attest opposite. The rise of Darcey Bussell to world acclaim, the forging of a superb partnership between Mukhamedov and Viviana Durante, this final, nostalgic and beautiful 2000-01 season - these are positive memories. He will be noted as a conservative, and many welcomed this after an insecure period of modernising under his predecessor, Norman Morrice. Whether conservatism has served the company well for the future, though, is debatable. In the shifting landscape of ballet, conservatism is not enough to hold steady. -

A Critical Analysis of 34Th Street Murals, Gainesville, Florida

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 A Critical Analysis of the 34th Street Wall, Gainesville, Florida Lilly Katherine Lane Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE 34TH STREET WALL, GAINESVILLE, FLORIDA By LILLY KATHERINE LANE A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2005 Copyright © 2005 All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Lilly Katherine Lane defended on July 11, 2005 ________________________________ Tom L. Anderson Professor Directing Dissertation ________________________________ Gary W. Peterson Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Dave Gussak Committee Member ________________________________ Penelope Orr Committee Member Approved: ____________________________________ Marcia Rosal Chairperson, Department of Art Education ___________________________________ Sally McRorie Dean, Department of Art Education The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ..…………........................................................................................................ v List of Figures .................................................................. -

A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov

Spring 2010 Ballet Revi ew From the Spring 2010 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland and Misha Chernov On the cover: New York City Ballet’s Tiler Peck in Peter Martins’ The Sleeping Beauty. 4 New York – Alice Helpern 7 Stuttgart – Gary Smith 8 Lisbon – Peter Sparling 10 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 11 New York – Sandra Genter 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 New York – Sandra Genter 17 Toronto – Gary Smith 19 New York – Marian Horosko 20 San Francisco – Paul Parish David Vaughan 45 23 Paris 1909-2009 Sandra Genter 29 Pina Bausch (1940-2009) Laura Jacobs & Joel Lobenthal 31 A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov Marnie Thomas Wood Edited by 37 Celebrating the Graham Anti-heroine Francis Mason Morris Rossabi Ballet Review 38.1 51 41 Ulaanbaatar Ballet Spring 2010 Darrell Wilkins Associate Editor and Designer: 45 A Mary Wigman Evening Marvin Hoshino Daniel Jacobson Associate Editor: 51 La Danse Don Daniels Associate Editor: Michael Langlois Joel Lobenthal 56 ABT 101 Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Larry Kaplan 61 Osipova’s Season Photographers: 37 Tom Brazil Davie Lerner Costas 71 A Conversation with Howard Barr Subscriptions: Don Daniels Roberta Hellman 75 No Apologies: Peck &Mearns at NYCB Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Annie-B Parson 79 First Class Teachers Associates: Peter Anastos 88 London Reporter – Clement Crisp Robert Gres kovic 93 Alfredo Corvino – Elizabeth Zimmer George Jackson 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 23 Paul Parish 100 Check It Out Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover photo by Paul Kolnik, New York City Ballet: Tiler Peck Sarah C. -

4Th MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE

th 4 MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, 17 TO 24 JANUARY, 2018 SOCIAL PROGRAMME: ROYAL PEDREGAL HOTEL ACADEMIC PROGRAMME: NATIONAL AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO Auditorio Alfonso Caso and Anexos de la Facultad de Derecho FINAL PROGRAMME (Online version linked to abstracts. Download PDF here) 1/47 All delegates please note: 1. Presentation slots may have needed to be moved by the organisers, and may appear in a different place from that of the final printed programme. Please consult the schedule located in the Conference Programme upon arrival at the Conference for your presentation time. 2. Please note that presenters have to ensure the following times for presentation to allow for adequate time for questions from the floor and smooth transition of sessions. Delegates must not stray from their allocated 20 minutes. Further, delegates are welcome to move within sessions, therefore presenters MUST limit their talk to the allocated time. Therefore, Q&A will be AFTER each talk, and NOT at the end of the three presentations. Plenary and Invited Talks – 45 min. presentation and 15 min. discussion (Q&A). 3. For panels, each panellist must stick strictly to a 10 minute time frame, before discussion with the floor commences. 4. Note that co-authors may be presenting at the conference in place of, or with the main author. For all co-authors, delegates are advised to consult the Conference Abstracts link on the Minding Animals website. Use of the term et al is provided where there is more than two authors of an abstract. 5. Moderator notes will be available at all front desks in tutorial rooms, along with Time Sheets (5, 3 and 1 minute Left). -

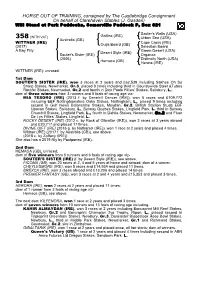

HORSE out of TRAINING, Consigned by the Castlebridge Consignment on Behalf of Clarehaven Stables (J

HORSE OUT OF TRAINING, consigned by The Castlebridge Consignment On behalf of Clarehaven Stables (J. Gosden) Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Somerville Paddock P, Box 821 Sadler's Wells (USA) Galileo (IRE) 358 (WITH VAT) Urban Sea (USA) Australia (GB) Cape Cross (IRE) WITTNER (IRE) Ouija Board (GB) (2017) Selection Board A Bay Filly Green Desert (USA) Desert Style (IRE) Souter's Sister (IRE) Organza (2006) Distinctly North (USA) Hemaca (GB) Herora (IRE) WITTNER (IRE): unraced. 1st Dam SOUTER'S SISTER (IRE), won 3 races at 2 years and £62,539 including Sakhee Oh So Sharp Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3, placed 8 times including third in Countrywide Steel &Tubes Rockfel Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2 and fourth in Dick Poole Fillies’ Stakes, Salisbury, L.; dam of three winners from 3 runners and 5 foals of racing age viz- MIA TESORO (IRE) (2013 f. by Danehill Dancer (IRE)), won 5 races and £109,772 including EBF Nottinghamshire Oaks Stakes, Nottingham, L., placed 9 times including second in Gulf News Balanchine Stakes, Meydan, Gr.2, British Stallion Studs EBF Upavon Stakes, Salisbury, L., Betway Quebec Stakes, Lingfield Park, L. third in Betway Churchill Stakes, Lingfield Park, L., fourth in Dahlia Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2 and Fluer De Lys Fillies’ Stakes, Lingfield, L. ROCKY DESERT (IRE) (2012 c. by Rock of Gibraltar (IRE)), won 2 races at 3 years abroad and £20,717 and placed 17 times. DIVINE GIFT (IRE) (2016 g. by Nathaniel (IRE)), won 1 race at 2 years and placed 4 times. Wittner (IRE) (2017 f. by Australia (GB)), see above. -

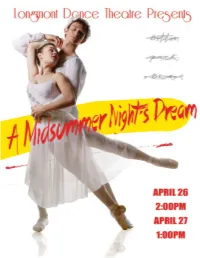

AMND-Program-Final.Pdf

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR KRISTIN KINGSLEY Story & Selected Lyrics from WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE Music by FELIX MENDELSSOHN Ballet Mistress STEPHANIE TULEY Music Director/Conductor BRANDON MATTHEWS Production Design SEAN COCHRAN Technical Director ISAIAH BOOTHBY Lighting Design DAVID DENMAN Costume Design NAOMI PRENDERGAST, SUSIE FAHRING, ANN MARCECA, & WANDA RICE WITH STRACCI FOR DANCE NIWOT HIGH SCHOOL AUDITORIUM APRIL 26 2:00PM APRIL 27 1:00PM Longmont Dance Theatre Our mission is simply stated but it is not simple to achieve: we strive to enliven and elevate the human spirit by means of dance, specifically the perfect form of dance known as ballet. A technique of movement that was born in the courts of kings and queens, ballet has survived to this day to become one of the most elegant, most adaptable and most powerful means of human communication. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR BALLET MISTRESS Kristin Kingsley Stephanie Tuley LDT BOARD OF DIRECTORS RESIDENT OPERATION PERSONNEL President Susan Burton Production & Design Vice President Dolores Kingsley Lighting Designer/ David Denman Secretary Marcella Cox Production Stage Manager Members Sean Cochran, Jeanine Hedstrom, Eileen Hickey, Stage Manager Jenn Zavattaro David Kingsley, & Moriah Sullivan Technical Dir./Master Carpenter Isaiah Boothby Ballet Guild Liason Cathy McGovern Scenic Design & Fabrication Sean Cochran with Enigma Concepts and Designs Properties Coordinator Lisa Taft House Manager Marcella Cox RESIDENT COMPANY MANAGEMENT Auditorium Manager Jason Watkins (Niwot HS Auditorium) Willow McGinty Office -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Al-'Usur Al-Wusta, Volume 23 (2015)

AL-ʿUṢŪR AL-WUSṬĀ 23 (2015) THE JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EAST MEDIEVALISTS About Middle East Medievalists (MEM) is an international professional non-profit association of scholars interested in the study of the Islamic lands of the Middle East during the medieval period (defined roughly as 500-1500 C.E.). MEM officially came into existence on 15 November 1989 at its first annual meeting, held ni Toronto. It is a non-profit organization incorporated in the state of Illinois. MEM has two primary goals: to increase the representation of medieval scholarship at scholarly meetings in North America and elsewhere by co-sponsoring panels; and to foster communication among individuals and organizations with an interest in the study of the medieval Middle East. As part of its effort to promote scholarship and facilitate communication among its members, MEM publishes al-ʿUṣūr al-Wusṭā (The Journal of Middle East Medievalists). EDITORS Antoine Borrut, University of Maryland Matthew S. Gordon, Miami University MANAGING EDITOR Christiane-Marie Abu Sarah, University of Maryland EDITORIAL BOARD, BOARD OF DIRECTORS, AL-ʿUṢŪR AL-WUSṬĀ (THE JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EAST MEDIEVALISTS) MIDDLE EAST MEDIEVALISTS Zayde Antrim, Trinity College President Sobhi Bourdebala, University of Tunis Matthew S. Gordon, Miami University Muriel Debié, École Pratique des Hautes Études Malika Dekkiche, University of Antwerp Vice-President Fred M. Donner, University of Chicago Sarah Bowen Savant, Aga Khan University David Durand-Guédy, Institut Français de Recherche en Iran and Research -

Finding Aid for Bolender Collection

KANSAS CITY BALLET ARCHIVES BOLENDER COLLECTION Bolender, Todd (1914-2006) Personal Collection, 1924-2006 44 linear feet 32 document boxes 9 oversize boxes (15”x19”x3”) 2 oversize boxes (17”x21”x3”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x4”) 1 oversize box (32”x19”x6”) 8 storage boxes 2 storage tubes; 1 trunk lid; 1 garment bag Scope and Contents The Bolender Collection contains personal papers and artifacts of Todd Bolender, dancer, choreographer, teacher and ballet director. Bolender spent the final third of his 70-year career in Kansas City, as Artistic Director of the Kansas City Ballet 1981-1995 (Missouri State Ballet 1986- 2000) and Director Emeritus, 1996-2006. Bolender’s records constitute the first processed collection of the Kansas City Ballet Archives. The collection spans Bolender’s lifetime with the bulk of records dating after 1960. The Bolender material consists of the following: Artifacts and memorabilia Artwork Books Choreography Correspondence General files Kansas City Ballet (KCB) / State Ballet of Missouri (SBM) files Music scores Notebooks, calendars, address books Photographs Postcard collection Press clippings and articles Publications – dance journals, art catalogs, publicity materials Programs – dance and theatre Video and audio tapes LK/January 2018 Bolender Collection, KCB Archives (continued) Chronology 1914 Born February 27 in Canton, Ohio, son of Charles and Hazel Humphries Bolender 1931 Studied theatrical dance in New York City 1933 Moved to New York City 1936-44 Performed with American Ballet, founded by