Canada's National Ballet School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gp 3.Qxt 7/11/16 9:01 AM Page 1

07-28 Winter's Tale_Gp 3.qxt 7/11/16 9:01 AM Page 1 July 13 –31, 2 016 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 28–31 David H. Koch Theater The National Ballet of Canada Karen Kain, Artistic Director The Winter’s Tale The National Ballet of Canada Orchestra Music Director and Principal Conductor David Briskin Approximate running time: 2 hours and 35 minutes, with two intermissions This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. The Lincoln Center Festival 2016 presentation of The Winter’s Tale is made possible in part by generous support from The LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust and Jennie and Richard DeScherer. Additional support is provided by The Joelson Foundation. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2016 presentation of The Winter’s Tale is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. Public support for Festival 2016 is provided by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and New York State Council on the Arts. The National Ballet of Canada’s lead philanthropic support for The Winter’s Tale is provided by The Catherine and Maxwell Meighen Foundation, Richard M. Ivey, C.C., an anonymous friend of the National Ballet, and The Producers’ Circle. The National Ballet of Canada gratefully acknowledges the generous support of The Honourable Margaret Norrie McCain, C.C. A co-production of The National Ballet of Canada and The Royal Ballet 07-28 Winter's Tale_Gp 3.qxt 7/11/16 9:01 AM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2016 THE WINTER’S -

National Ballet of Canada Under the Direction of CELIA FRANCA

The Universit~ Mnsiual Souiety \ 01 ~ The UniversitJ of Michigan Presents National Ballet of Canada under the direction of CELIA FRANCA FRIDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 17,1969, AT 8:30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN KAREN BOWES NADIA POTTS VERONICA TENNANT MARIJAN BAYER JEREMY BLANTON GLE!\TN GILMOUR EARL KRAUL HAZAROS SURMEJAN ELAINE CRAWFORD LINDA FLETCHER VANESSA HARWOOD MARY J AGO MAUREEN ROTHWELL MURRAY KILGOUR ANDREW OXENHAM CLINTON ROTHWELL Victoria Bertram Gerre Cimino Colleen Cool Christy Cumberland Ann Ditchburn Lorna Geddes Rosemary Jeanes Karen Kain Stephanie Leigh Barbara Malinowski Linda Maybarduk Bardi Norman Patricia Oney Kevyn O'Rourke Barbara Sherval Charmain Turner Amanda Vaughan Christopher Bannerman Lawrence Beevers David Gordon Jacques Gorrissen Charles Kirby Christopher Knobbs Alastair Munro Tomas Schramek Brian Scott Timothy Spain Leonard Stepanick Associate Artistic Director R esident Choreographer BETTY OLIPHANT GRANT STRATE THE NATIONAL BALLET ORCHESTRA Musical Director and Conductor, GEORGE CRUM Assistant Conductor, CAMPBELL JOHNSON Concert Mistress, ISABEL VrLA Ballet Master, DAVID SCOTT Ballet Mistress, JOANNE NISBET First Program Second Annual Dance Series Complete Programs 3662 PROGRAM SOLITAIRE "A kind of game for one" Music: MALCOLM ARNOLD Choreography: KENNETH MAcMILLAN Decor and Costumes: LAWRENCE SCHAFER Conductor: CAMPBELL JOHNSON VANESSA HARWOOD Linda Fletcher Jeremy Blanton Murray Kilgo ur Andrew Oxenham Victoria Bertram Karen Kain Bardi Norman Patricia Oney Kevin O'Rourke Amanda Vaughan Lawrence -

1976-77-Annual-Report.Pdf

TheCanada Council Members Michelle Tisseyre Elizabeth Yeigh Gertrude Laing John James MacDonaId Audrey Thomas Mavor Moore (Chairman) (resigned March 21, (until September 1976) (Member of the Michel Bélanger 1977) Gilles Tremblay Council) (Vice-Chairman) Eric McLean Anna Wyman Robert Rivard Nini Baird Mavor Moore (until September 1976) (Member of the David Owen Carrigan Roland Parenteau Rudy Wiebe Council) (from May 26,1977) Paul B. Park John Wood Dorothy Corrigan John C. Parkin Advisory Academic Pane1 Guita Falardeau Christopher Pratt Milan V. Dimic Claude Lévesque John W. Grace Robert Rivard (Chairman) Robert Law McDougall Marjorie Johnston Thomas Symons Richard Salisbury Romain Paquette Douglas T. Kenny Norman Ward (Vice-Chairman) James Russell Eva Kushner Ronald J. Burke Laurent Santerre Investment Committee Jean Burnet Edward F. Sheffield Frank E. Case Allan Hockin William H. R. Charles Mary J. Wright (Chairman) Gertrude Laing J. C. Courtney Douglas T. Kenny Michel Bélanger Raymond Primeau Louise Dechêne (Member of the Gérard Dion Council) Advisory Arts Pane1 Harry C. Eastman Eva Kushner Robert Creech John Hirsch John E. Flint (Member of the (Chairman) (until September 1976) Jack Graham Council) Albert Millaire Gary Karr Renée Legris (Vice-Chairman) Jean-Pierre Lefebvre Executive Committee for the Bruno Bobak Jacqueline Lemieux- Canadian Commission for Unesco (until September 1976) Lope2 John Boyle Phyllis Mailing L. H. Cragg Napoléon LeBlanc Jacques Brault Ray Michal (Chairman) Paul B. Park Roch Carrier John Neville Vianney Décarie Lucien Perras Joe Fafard Michael Ondaatje (Vice-Chairman) John Roberts Bruce Ferguson P. K. Page Jacques Asselin Céline Saint-Pierre Suzanne Garceau Richard Rutherford Paul Bélanger Charles Lussier (until August 1976) Michael Snow Bert E. -

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of ARTS MANAGEMENT

VOLUME 9, NUMBER 2 • WINTER 2007 HEC M o n t r é a l ~ AIMAC Karen Kain and the INTERNATIONAL National Ballet of Canada Jacqueline Cardinal, Laurent Lapierre JOURNAL of ARTS MANAGEMENT The Futurist Stance of Historical Societies: An Analysis of Position Statements Dirk H.R. Spennemann Volunteer Management in Arts Organizations: A Case Study and Managerial Implications Helen Bussell, Deborah Forbes Letting Go of the Reins: Paradoxes and Puzzles in Leading an Artistic Enterprise Ralph Bathurst, Lloyd Williams, Anne Rodda A Scale for Measuring Aesthetic Style in the Field of Luxury and Art Products Joëlle Lagier, Bruno Godey Why Occasional Theatregoers in France Do Not Become Subscribers Christine Petr C OMPANY PROFILE Karen Kain and the National Ballet of Canada Jacqueline Cardinal, Laurent Lapierre Moscow International Ballet competition, I hate the superficiality of small Kain was invited to perform on the world’s talk. I have dedicated my career most celebrated stages. Beautiful inside as well to getting to the heart of com- as out, endowed with an extraordinary dra- munication in body language, matic intensity and trained for seven years in stripping off whatever is super- the demanding Ceccheti technique, she had fluous. Embellishment isn’t my always dreamed of dancing the part of Giselle Jacqueline Cardinal is a in the ballet of the same name. Kain’s mother Research Associate with style; I try to distil the essence, took her to see Giselle on her eighth birthday, the Pierre Péladeau Chair of and remain uncomfortable with and her future was decided that day. Leadership at HEC Montréal. -

DOCTORAL THESIS the Dancer's Contribution: Performing Plotless

DOCTORAL THESIS The Dancer's Contribution: Performing Plotless Choreography in the Leotard Ballets of George Balanchine and William Forsythe Tomic-Vajagic, Tamara Award date: 2013 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 THE DANCER’S CONTRIBUTION: PERFORMING PLOTLESS CHOREOGRAPHY IN THE LEOTARD BALLETS OF GEORGE BALANCHINE AND WILLIAM FORSYTHE BY TAMARA TOMIC-VAJAGIC A THESIS IS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF DANCE UNIVERSITY OF ROEHAMPTON 2012 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the contributions of dancers in performances of selected roles in the ballet repertoires of George Balanchine and William Forsythe. The research focuses on “leotard ballets”, which are viewed as a distinct sub-genre of plotless dance. The investigation centres on four paradigmatic ballets: Balanchine’s The Four Temperaments (1951/1946) and Agon (1957); Forsythe’s Steptext (1985) and the second detail (1991). -

2004 Cecchetti Newsletter V3

CECCHETTI INTERNATIONAL CLASSICAL BALLET Newsletter No. 10, 2004 Mission Statement: to foster the development of the method to develop training for the future to keep alive the essence of the method’s historical tradition Enrico Cecchetti as to raise the profile of the method world-wide Kastchei in L’Oiseau de feu (Firebird) with the to encourage the profession and the art of dance by interaction Ballets Russes, at the between members and the international dance profession Paris Opera, 1910. Photographic negatives to enhance the status of dance in the context by Raffaello Bencini. of the arts and education Photo courtesy of Dance Collection Danse Letter from the Chairman Dear Members and Friends of Cecchetti International - Classical Ballet (CICB) It is with great delight that we can tell you that our international organization is now a legal non-profit entity. We were incorpo- rated in Canada on July 2nd, 2004 and we thank the Canadian delegates for facilitating this. Congratulations to everyone, and welcome to Cecchetti International - Classical Ballet. The Corporate Members of CICB have had an inaugural teleconference. Matters needing clarification were discussed, and over all it was an excellent meeting. Hereunder are set out the categories of membership of our new International Society, so that all our members can understand their standing in the new organization. a) Corporate Members - there are six corporate members who have come together to promote the Cecchetti Method and comprise the Board of CICB. Cecchetti Societies of: Australia, Canada, Southern Africa, and USA Cecchetti Council of America, Danzare Cecchetti - ANCEC Italia also represented are Korea, Malaysia, Namibia, New Zealand Thailand and Zimbabwe b) Represented Members - we are all Represented Members if we belong to one of the six Societies above and are in good standing with that society. -

Prima Ballerina Bio & Resume

Veronica Tennant, C.C. Prima Ballerina Bio & Resume Veronica Tennant, during her illustrious 25-year career as Prima Ballerina with The National Ballet of Canada - won a devoted following on the international stage as a dancer of extraordinary versatility and dramatic power. Born in London England, Veronica Tennant started ballet lessons at four at the Arts Educational School, and with her move to Canada at the age of nine, started training with Betty Oliphant and then the National Ballet School. While she missed a year on graduation due to her first back injury, she entered the company in 1964 as its youngest principal dancer. Tennant was chosen by Celia Franca and John Cranko for her debut as Juliet. She went on to earn accolades in every major classical role and extensive neo-classical repertoire as well as having several contemporary ballets choreographed for her. She worked with the legendary choreographers; Sir Frederick Ashton, Roland Petit, Jiri Kylian, John Neumeier, and championed Canadian choreographers such as James Kudelka, Ann Ditchburn, Constantin Patsalas and David Allan. She danced across North and South America, Europe and Japan, with the greatest male dancers of our time, including Erik Bruhn (her mentor), and Rudolf Nureyev, Anthony Dowell, Peter Schaufuss, Fernando Bujones and Mikhail Baryshnikov (immediately after he defected in Toronto, 1974). She was cast by Erik Bruhn to dance his La Sylphide with Niels Kehlet when Celia Franca brought The National Ballet of Canada to London England for the first time in 1972; and was Canada’s 'first Aurora' dancing in the premiere of Rudolf Nureyev's Sleeping Beauty September 1, 1972 and at the company's debut at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, 1973. -

The Nutcracker December 13, 2014 – January 3, 2015

Ballet Notes Presents The Nutcracker December 13, 2014 – January 3, 2015 Jonathan Renna. Photo by Aleksandar Antonijevic. Orchestra Violin 1 Flutes Elissa Lee, Leslie J. Allt, Principal Guest Concertmaster Shelley Brown, Piccolo* (Dec 13 - 23) Kevin O’Donnell, Piccolo+ Aaron Schwebel, Maria Pelletier Guest Concertmaster (Dec 23 - Jan 3) Oboes Lynn Kuo, Mark Rogers, Principal Assistant Concertmaster Karen Rotenberg James Aylesworth Lesley Young, Jennie Baccante English Horn Sheldon Grabke Clarinets Celia Franca, C.C., Founder Nancy Kershaw Max Christie, Principal Sonia Klimasko-Leheniuk Gary Kidd, Bass Clarinet George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Yakov Lerner Emily Marlow* + Karen Kain, C.C. Barry Hughson Jayne Maddison Aiko Oda Wendy Rogers Colleen Cook+ Artistic Director Executive Director Paul Zevenhuizen Bassoons David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Violin 2 Stephen Mosher, Principal Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Dominique Laplante, Jerry Robinson Principal Conductor Principal Second Violin Elizabeth Gowen, Aaron Schwebel, Contra-Bassoon Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Assistant Principal Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, 2nd Violin* Horns YOU dance / Ballet Master Jayne Maddison, Acting Gary Pattison, Principal Assistant Principal Vincent Barbee* Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne 2nd Violin (Dec 13 & 14) Derek Conrod Senior Ballet Master Richardson Diane Doig+ Csaba Koczó, Acting + Senior Ballet Mistress Assistant Principal Christine Passmore 2nd Violin Scott Wevers Guillaume Côté, Greta Hodgkinson, Svetlana Lunkina, (Dec -

Veronica Tennant, Prima Ballerina with the National Ballet of Canada for 25 Years, Won Hearts and Accolades on the National and International Ballet Stage

VERONICA TENNANT, C.C.; D.LITT; LL.D ~ (h.c.) 1 1 Veronica Tennant, Prima Ballerina with The National Ballet of Canada for 25 years, won hearts and accolades on the national and international ballet stage. Since 1989, she has been recognized as a gifted filmmaker, producer/director, speaker/narrator and writer, with her works garnering several awards, including the International Emmy Award. In 2004, Veronica Tennant was awarded the prestigious Governor General’s Performing Arts Award for Lifetime Achievement, and was announced by the Canada Council, as the recipient of the Walter Carsen Prize for Excellence in the Performing Arts. As the first dancer to be appointed to the Order of Canada as Officer in 1975, Veronica Tennant was promoted in 2003, for the breadth of her contribution to the arts in Canada, to the rank of Companion, which is the country’s highest honour. During Veronica Tennant’s illustrious career, she won a devoted following as a dancer of extraordinary versatility and dramatic power. Entering the company at 18, as it’s youngest Principal Dancer she was cast by Celia Franca as Juliet in John Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet. She earned accolades in every major classical role as well as having several ballets choreographed for her, dancing on stages across North America, Europe and Japan, with the greatest male dancers of our time, including Erik Bruhn, Rudolf Nureyev, Anthony Dowell and Mikhail Baryshnikov. She gave her farewell performance in 1989: A Passion for Dance: Celebrating the Tennant Magic. Overlapping from the National Ballet in 1989, Tennant was the host, creative consultant/writer of Sunday Arts Entertainment for three seasons on CBC Television. -

Celia Franca Albums

FINDING AID FOR CELIA FRANCA PHOTOS – 2007 DONATION TO LAC ALBUMS R4290 Volume 88 Brown ornate cover Shanghai Dance School and Shanghai Ballet Company 29 black and white photos of CF with children and young dancers in a studio Green ornate cover Celia Franca and James Morton in China 15 b&w photos of JM and CF meeting with people and JM teaching music students and at a reception R4290 Volume 86 Pink album with diamond pattern labeled Beijing dated June 10, 1980 Celia Franca and James Morton in China 36 b&w photos primarily of CF with students in classes 4 colour photographs Pink album labeled Beijing Celia Franca in China 34 b&w photos of CF with students walking, eating and dancing Maroon album with dragon pattern on cover Ballet company in China 20 7x9 b&w photographs mainly of ballet performances with a few of students in dance studio class R4290 Volume 87 Brown album National Ballet of Canada 35th Anniversary Gala held at O’Keefe Centre. February 25, 1987 “Copies of Myrna Aaron’s photos” 88 colour photographs of those attending the gala, primarily 5x7s R4290 Volume 88 Navy blue album Commemorative album given to CF by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario Arts for Hearts Benefit, 2000 37 primarily 5x7 colour photos of attendees including Mitchell Sharp and wife, Marianne Scott and Hamilton Southam R4290 Volume 85 Black binder Commemorative photographs from opening of the Celia Franca Centre in Toronto 24 colour digital scans PERSONAL PHOTOGRAPHS R4290 Volume 80 Folder 1 Photographs of CF as a young child, with her parents -

The Case of David Allan's 1987 Ballet Masada: Did It Matter That the Topic

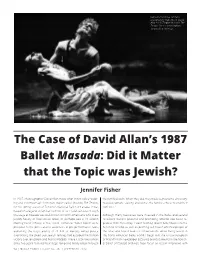

Dancers Veronica Tennant and Gregory Osborne in David Allan's 1987 ballet Masada: The Zealots. Photo: John Mahler/ Toronto Star Archives The Case of David Allan’s 1987 Ballet Masada: Did it Matter that the Topic was Jewish? Jennifer Fisher In 1987, choreographer David Allan made what critics called “a dar- the fortified walls. When they did, they made a gruesome discovery: ing and controversial” 40-minute ballet called Masada, The Zealots, to avoid capture, slavery, and worse, the families chose to end their for the spring season of Toronto’s National Ballet of Canada. It was own lives.1 based on a legend unfamiliar to most of its 27-dancer-cast, though the siege at Masada was well-known to North Americans who knew Although many resources were invested in the ballet and several Jewish history or had visited Israel, or perhaps saw a TV version reviewers found it powerful and promising, Masada was never re- starring Peter O’Toole in the 1980s. Historical “Ballet Notes” were peated. With this essay, I want to bring Allan’s ballet back into the provided to the press and to audiences in pre-performance talks, historical record, as well as pointing out how it affected people at explaining the tragic events of 74 A.D. at Herod’s winter palace the time, and how it leads to conversations about being Jewish in overlooking the Dead Sea. Jewish families had escaped the Roman the North American ballet world. I begin with the critical reception victory over Jerusalem and fled to Masada. There it took the Roman of Masada from newspaper accounts and documents in the Nation- army two years to build their siege ramp and finally break through al Ballet of Canada archives, then focus on recent interviews with 54 | DANCE TODAY | ISSUE No. -

MA Thesis Document

DANCING FOR CANADA/DANCING BEYOND CANADA: THE HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL BALLET OF CANADA AND THE ROYAL WINNIPEG BALLET’S INTERNATIONAL TOURS, 1958-1974. by Nadia van Asselt A thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada Final (QSpace) submission May, 2021 Copyright ©Nadia van Asselt, 2021 Abstract This thesis traces the growth of the National Ballet of Canada (NBC) and the Royal Winnipeg Ballet (RWB) through international ballet exchanges and reveals how foundational they were to the companies’ current reputations. In the mid-twentieth century, the development of Canadian ballet was intertwined with international exchanges because the Canada Council of the Arts viewed national success as synonymous with international success. The National Ballet of Canada and the Royal Winnipeg Ballet developed different ways of being viewed as Canadian while abroad and established themselves as noteworthy cultural institutions. This thesis is also a study of the non-state actors’ role – ballet companies’ personnel, artistic directors, dancers, and media – in producing or furthering diplomatic relations with host countries and how they either upheld or contradicted state interests. Chapter two examines ten years (1958-1968) of negotiations between the NBC and the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes to show how the NBC used Canadian cultural policies and Canada’s national language to attain international tours that focused on fostering the company’s growth. Also, the tour resulted in the NBC building a relationship with Mexico without much help from the government. Chapter three studies the RWB’s engagement with Jamaica for the country’s independence celebrations in 1963 from the perspective of non-state actors – the dancers, media, and private sectors – to understand the motivations in carrying out state interest.