Dancing the Cold War an International Symposium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bloch Dance World Cup Finals 2016 Schedule Overview Saturday 25 June – Saturday 2 July

Bloch Dance World Cup Finals 2016 Schedule Overview Saturday 25 June – Saturday 2 July Saturday - Morning 09:30 MiniSW - Mini Solo Jazz & Show Dance MiniSM - Mini Solo Modern & Contemporary Dance KDM - Children Duet/Trio Modern & Contemporary Dance PRIZE GIVING Saturday - Evening 19:00 KSV - Children Solo Song & Dance MiniSV - Mini Solo Song and Dance KDV - Children Duet/Trio Song & Dance MiniDV - Mini Duet/Trio Song & Dance KQV - Children Quartet/Quad Song & Dance MiniQV - Mini Quartet/Quad Song & Dance PRIZE GIVING Sunday - Morning 08:30 KST - Children Solo Tap MiniST - Mini Solo Tap KGT - Children Group Tap PRIZE GIVING KGV - Children Group Song & Dance MiniDT - Mini Duet/Trio Tap KQM - Children Quartet/Quad Modern Dance (any style) PRIZE GIVING Sunday - Afternoon 13:15 MiniGT - Mini Group Tap KQT - Children Quartet/Quad Tap MiniSA - Mini Solo Acro Dance PRIZE GIVING KSA - Children Solo Acro Dance MiniGV - Mini Group Song & Dance KDT - Children Duet/Trio Tap MiniQT - Mini Quartet/Quad Tap KSH - Children Solo Hip Hop & Street Dance PRIZE GIVING Bloch Dance World Cup Finals 2016 Schedule Overview Saturday 25 June – Saturday 2 July Sunday - Evening 18:30 KGM - Children Group Modern & Contemporary Dance KDH - Children Duet/Trio Hip Hop & Street Dance MiniGA - Mini Group Acro Dance KGH - Children Group Hip Hop & Street Dance KGA - Children Group Acro Dance PRIZE GIVING Monday - Morning 08:30 KDW - Children Duet/Trio Jazz & Show Dance MiniQM - Mini Quartet/Quad Modern (any style age appropriate) KSN - Children Solo National & Folklore Dance -

Queer As Alla: Subversion And/Or Re-Affirmation of the Homophobic Nationalist Discourse of Normality in Post-Soviet Vilnius

RASA NAVICKAITE Queer as Alla: Subversion and/or re-affirmation of the homophobic nationalist discourse of normality in post-Soviet Vilnius IF YOU ARE non-heterosexual and you live in Vilnius, then gay- friendly options for going out are pretty limited for you. You would probably end up in the same place each weekend – a little under- ground gay club, called Soho. While for the gay community it is a well-known place to have drinks, to dance and to flirt, those who do not clearly identify as lesbian, gay, bi or trans usually have never even heard about this place. And those who do hear about it tend to imagine it as a place ”outside” the boundaries of normality and mo- rality, a place for those who live on the margins of society, delimited according to the axis of sexuality, or, to put it in a coarse language – a ”nest of whores” (Tereškinas 2004, 32). Although the times of the totalitarian Communist regime are gone since more than twenty years, the strict boundaries between what is normal and what is not, persist and in some cases have be- come even more rigid (Stukuls 1999, 537). The high level of soci- etal homophobia,1 encouraged by nationalist discourse is a perfect example of this boundary control. Although LGBT organisations present visibility and openness of non-heteronormative sexualities lambda nordica 4/2012 127 © Föreningen Lambda Nordica 2012 Queer as Alla as their main goal, it does not change the situation, where the ma- jority of gays are ”in the closet” (Atviri.lt 2012a). -

Forced Labour in Serbia Producers, Consumers and Consequences of Forced Labour 1941 - 1944

Forced Labour in Serbia Producers, Consumers and Consequences of Forced Labour 1941 - 1944 edited by: Sanela Schmid Milovan Pisarri Tomislav Dulić Zoran Janjetović Milan Koljanin Milovan Pisarri Thomas Porena Sabine Rutar Sanela Schmid 1 Project partners: Project supported by: Forced Labour in Serbia 2 Producers, Consumers and Consequences . of Forced Labour 1941 - 1944 This collection of scientific papers on forced labour during the Second World War is part of a wider research within the project "Producers, Consumers and Consequences of Forced Labour - Serbia 1941-1944", which was implemented by the Center for Holocaust Research and Education from Belgrade in partnership with Humboldt University, Berlin and supported by the Foundation "Remembrance, Responsibility and Future" in Germany. ("Stiftung Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft" - EVZ). 3 Impressum Forced Labour in Serbia Producers, Consumers and Consequences of Forced Labour 1941-1944 Published by: Center for Holocaust Research and Education Publisher: Nikola Radić Editors: Sanela Schmid and Milovan Pisarri Authors: Tomislav Dulić Zoran Janjetović Milan Koljanin Milovan Pisarri Thomas Porena Sabine Rutar Sanela Schmid Proofreading: Marija Šapić, Marc Brogan English translation: Irena Žnidaršić-Trbojević German translation: Jovana Ivanović Graphic design: Nikola Radić Belgrade, 2018. Project partners: Center for Holocaust Research and Education Humboldt University Berlin Project is supported by: „Remembrance, Responsibility And Future“ Foundation „Stiftung Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft“ - EVZ Forced Labour in Serbia 4 Producers, Consumers and Consequences . of Forced Labour 1941 - 1944 Contents 6 Introduction - Sanela Schmid and Milovan Pisarri 12 Milovan Pisarri “I Saw Jews Carrying Dead Bodies On Stretchers”: Forced Labour and The Holocaust in Occupied Serbia 30 Zoran Janjetović Forced Labour in Banat Under Occupation 1941 - 1944 44 Milan Koljanin Camps as a Source of Forced Labour in Serbia 1941 - 1944 54 Photographs 1 62 Sabine Rutar Physical Labour and Survival. -

Great Gig DANCE Co

great gig DANCE co. 4200 Wade Green Road, Suite #128, Kennesaw GA 30144 • 770.218.2112 • www.greatgigdance.com INFORMATION & POLICIES (2021-2022) Season Our season lasts 40 weeks or 10 months (August 9, 2021 through June 4, 2022). We will be closed the week of Thanksgiving (November 21-28), two weeks during the Winter holidays (December 19-January 2) and one week during Spring Break (April 3-April 10). We will be open all other holidays, including all the Monday Holidays and other school breaks! We will close for inclement weather if necessary—please check our website and Facebook page or call us for updates on snow closings. Tuition and Fees 45-minute class $60 monthly 1-hour class $68 monthly 1-1/2 hour class $80 monthly • Each student registered for 2 or more classes will receive a 10% discount on their total tuition. • Additional family members will receive a 10% discount on their tuition (not in addition to the multi-class discount). • Tuition paid as one annual payment will receive an additional 10% discount. This payment must be made by September 15th. All tuition payments are non-refundable. • There is a $40 registration fee per season per family. This fee is non-refundable. • Tuition is due on the 15th of each month. • A $15 late fee will be charged for payments that are 1 week late. • A $25 fee will be charged for any checks with insufficient funds. • Tuition is a monthly fee and will not be pro-rated based on holidays or missed classes. Tuition is non- refundable. -

The Rise of Guangchangwu in a Chinese Village

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 4499–4522 1932–8036/20170005 Reading Movement in the Everyday: The Rise of Guangchangwu in a Chinese Village MAGGIE CHAO Simon Fraser University, Canada Communication University of China, China Over recent years, the practice of guangchangwu has captured the Chinese public’s attention due to its increasing popularity and ubiquity across China’s landscapes. Translated to English as “public square dancing,” guangchangwu describes the practice of group dancing in outdoor spaces among mostly middle-aged and older women. This article examines the practice in the context of guangchangwu practitioners in Heyang Village, Zhejiang Province. Complicating popular understandings of the phenomenon as a manifestation of a nostalgic yearning for Maoist collectivity, it reads guangchangwu through the lens of “jumping scale” to contextualize the practice within the evolving politics of gender in post-Mao China. In doing so, this article points to how guangchangwu can embody novel and potentially transgressive movements into different spaces from home to park, inside to outside, and across different scales from rural to urban, local to national. Keywords: square dancing, popular culture, spatial practice, scale, gender politics, China The time is 7:15 p.m., April 23, 2015, and I am sitting adjacent to a small, empty square tucked away from the main thoroughfare of a university campus in Beijing. As if on cue, Ms. Wu appears, toting a small loudspeaker on her hip.1 She sets it down on the stairs, surveying the scene before her: a small flat space, wedged in between a number of buildings, surrounded by some trees, evidence of a meager attempt at beautifying the area. -

18Th Century Dance

18TH CENTURY DANCE THE 1700’S BEGAN THE ERA WHEN PROFESSIONAL DANCERS DEDICATED THEIR LIFE TO THEIR ART. THEY COMPETED WITH EACH OTHER FOR THE PUBLIC’S APPROVAL. COMING FROM THE LOWER AND MIDDLE CLASSES THEY WORKED HARD TO ESTABLISH POSITIONS FOR THEMSELVES IN SOCIETY. THINGS HAPPENING IN THE WORLD IN 1700’S A. FRENCH AND AMERICAN REVOLUTIONS ABOUT TO HAPPEN B. INDUSTRIALIZATION ON THE WAY C. LITERACY WAS INCREASING DANCERS STROVE FOR POPULARITY. JOURNALISTS PROMOTED RIVALRIES. CAMARGO VS. SALLE MARIE ANNE DE CUPIS DE CAMARGO 1710 TO 1770 SPANISH AND ITALIAN BALLERINA BORN IN BRUSSELS. SHE HAD EXCEPTIONAL SPEED AND WAS A BRILLIANT TECHNICIAN. SHE WAS THE FIRST TO EXECUTE ENTRECHAT QUATRE. NOTEWORTHY BECAUSE SHE SHORTENED HER SKIRT TO SEE HER EXCEPTIONAL FOOTWORK. THIS SHOCKED 18TH CENTURY STANDARDS. SHE POSSESSED A FINE MUSICAL SENSE. MARIE CAMARGO MARIE SALLE 1707-1756 SHE WAS BORN INTO SHOW BUSINESS. JOINED THE PARIS OPERA SALLE WAS INTERESTED IN DANCE EXPRESSING FEELINGS AND PORTRAYING SITUATIONS. SHE MOVED TO LONDON TO PUT HER THEORIES INTO PRACTICE. PYGMALION IS HER BEST KNOWN WORK 1734. A, CREATED HER OWN CHOREOGRAPHY B. PERFORMED AS A DRAMATIC DANCER C. DESIGNED DANCE COSTUMES THAT SUITED THE DANCE IDEA AND ALLOWED FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT MARIE SALLE JEAN-GEORGES NOVERRE 1727-1820; MOST FAMOUS PERSON OF 18TH CENTURY DANCE. IN 1760 WROTE LETTERS ON DANCING AND BALLETS, A SERIES OF ESSAYS ATTACKING CHOREOGRAPHY AND COSTUMING OF THE DANCE ESTABLISHMENT ESPECIALLY AT PARIS OPERA. HE EMPHASIZED THAT DANCE WAS AN ART FORM OF COMMUNICATION: OF SPEECH WITHOUT WORDS. HE PROVED HIS THEORIES BY CREATING SUCCESSFUL BALLETS AS BALLET MASTER AT THE COURT OF STUTTGART. -

Iti-Info” № 3–4 (18–19) 2013

RUSSIAN NATIONAL CENTRE OF THE INTERNATIONAL THEATRE INSTITUTE «МИТ-ИНФО» № 3–4 (18–19) 2013 “ITI-INFO” № 3–4 (18–19) 2013 УЧРЕЖДЕН НЕКОММЕРЧЕСКИМ ПАРТНЕРСТВОМ ПО ПОДДЕРЖКЕ ESTABLISHED BY NON-COMMERCIAL PARTNERSHIP ТЕАТРАЛЬНОЙ ДЕЯТЕЛЬНОСТИ И ИСКУССТВА «РУССКИЙ FOR PROMOTION OF THEATRE ACTIVITITY AND ARTS НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ ЦЕНТР МЕЖДУНАРОДНОГО ИНСТИТУТА ТЕАТРА». «RUSSIAN NATIONAL CENTRE OF THE INTERNATIONAL ЗАРЕГИСТРИРОВАН ФЕДЕРАЛЬНОЙ СЛУЖБОЙ ПО НАДЗОРУ В СФЕРЕ THEATRE INSTITUTE» СВЯЗИ И МАССОВЫХ КОММУНИКАЦИЙ. REGISTERED BY THE FEDERAL AGENCY FOR MASS-MEDIA AND СВИДЕТЕЛЬСТВО О РЕГИСТРАЦИИ COMMUNICATIONS. REGISTRATION LICENSE SMI PI № FS77-34893 СМИ ПИ № ФС77–34893 ОТ 29 ДЕКАБРЯ 2008 ГОДА OF DECEMBER 29TH, 2008 АДРЕС РЕДАКЦИИ: 127055, УЛ. ТИХВИНСКАЯ, 10 EDITORIAL BOARD ADDRESS: 127055, MOSCOW, TIKHVINSKAYA STR., 10 ТЕЛЕФОНЫ РЕДАКЦИИ: +7 (499) 978-26-38, +7 (499) 978-28-52 PHONES: +7 (499) 978 2638, +7 (499) 978 2852 ФАКС: +7 (499) 978-29-70 FAX: +7 (499) 978 2970 ЭЛЕКТРОННАЯ ПОЧТА: [email protected] E-MAIL: [email protected] НА ОБЛОЖКЕ : СЦЕНА ИЗ СПЕКТАКЛЯ COVER: “THE ANIMALS AND CHILDREN «ЖИВОТНЫЕ И ДЕТИ ЗАНИМАЮТ УЛИЦЫ». TOOK TO THE STREETS”. 1927 (LONDON, GREAT BRITAIN) 1927 (LONDON, GREAT BRITAIN) ФОТОГРАФИИ ПРЕДОСТАВЛЕНЫ ОТДЕЛОМ ПО СВЯЗЯМ С PHOTOS ARE PROVIDED BY ОБЩЕСТВЕННОСТЬЮ ГЦТМ ИМЕНИ А.А.БАХРУШИНА, PR DEPARTMENT OF A.A.BAKHRUSHIN THEATRE MUSEUM, PRESS ПРЕСС-СЛУЖБАМИ ЧЕХОВСКОГО ФЕСТИВАЛЯ, ОРЕНБУРГСКОГО SERVICES OF CHEKHOV THEATRE FESTIVAL, ORENBURG DRAMA THEATRE ДРАМАТИЧЕСКОГО ТЕАТРА ИМЕНИ М.ГОРЬКОГО, СЛОВЕНСКИМ NAMED AFTER M.GORKY, SLOVENIAN CENTRE OF ITI, “DOCTOR- ЦЕНТРОМ МИТ, БЛАГОТВОРИТЕЛЬНОЙ ОРГАНИЗАЦИЕЙ «ДОКТОР- CLOWN” CHARITABLE ORGANIZATION, THE CENTRE КЛОУН», ЦЕНТРОМ ДРАМАТУРГИИ И РЕЖИССУРЫ, НАТАЛЬЕЙ OF DRAMA AND STAGE DIRECTION, NATALYA VOROZHBIT, ВОРОЖБИТ, ЛЕОНИДОМ БУРМИСТРОВЫМ LEONID BURMISTROV ГЛАВНЫЙ РЕДАКТОР: АЛЬФИРА АРСЛАНОВА EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: ALFIRA ARSLANOVA ЗАМ. -

Top Spots for Travel PAGE 14

DELIVERING BUSINESS ESSENTIALS TO NTA MEMBERS AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 2020 Top spots for travel PAGE 14 EXPERT ADVICE FOR GROUP LEADERS PAGE 8 MUSEUMS REVIVE AND RETELL PAGE 21 SILVER LININGS PAGE 52 Colorado National Monument DISCOUNTS AVAILABLE FOR GROUPS OF 15 OR MORE Your group can experience all Colonial Williamsburg has to oer with an experience designed to fit the requirements of day-trippers, groups on tight schedules, or those who want a structured experience. Stay at one of our ocial Colonial Williamsburg hotels and you will have a choice of premium, deluxe, or value accommodations, all just a short stroll to the Historic Area. Plus, you will enjoy Exclusive Guest Benefits—reduced pricing for admission tickets to the Historic Area and museums, preferred reservations, and more. Choose from a half-day, one-day, three-days, or annual ticket package. You may choose to have a Customized Guided Tour or explore on your own with our Self-Guided Tour option. Book your group trip today: call 1-800-228-8878, email [email protected], visit colonialwilliamsburg.org/grouptours CW-XXX-NTAGroupTripPlanner_8375x10875_wbleed_r1.indd 1 7/21/20 4:20 PM August/September 2020 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Here’s where groups go 4 From the Editor As groups gear up to get back on the road, Courier’s Bob 6 Voices of Leadership Rouse takes you on a journey to six great places across North Business America where travelers can enjoy a range of experiences. 7 InBrief vTREX, it’s what’s for 2020 ITMI, WFTA to be part of vTREX 14 NTA asks for U.S. -

Zhuk Outcover.Indd

The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies Sergei I. Zhuk Number 1906 Popular Culture, Identity, and Soviet Youth in Dniepropetrovsk, 1959–84 The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies Number 1906 Sergei I. Zhuk Popular Culture, Identity, and Soviet Youth in Dniepropetrovsk, 1959–84 Sergei I. Zhuk is Associate Professor of Russian and East European History at Ball State University. His paper is part of a new research project, “The West in the ‘Closed City’: Cultural Consumption, Identities, and Ideology of Late Socialism in Soviet Ukraine, 1964–84.” Formerly a Professor of American History at Dniepropetrovsk University in Ukraine, he completed his doctorate degree in Russian History at the Johns Hopkins University in 2002 and recently published Russia’s Lost Reformation: Peasants, Millennialism, and Radical Sects in Southern Russia and Ukraine, 1830–1917 (2004). No. 1906, June 2008 © 2008 by The Center for Russian and East European Studies, a program of the University Center for International Studies, University of Pittsburgh ISSN 0889-275X Image from cover: Rock performance by Dniepriane near the main building of Dniepropetrovsk University, August 31, 1980. Photograph taken by author. The Carl Beck Papers Editors: William Chase, Bob Donnorummo, Ronald H. Linden Managing Editor: Eileen O’Malley Editorial Assistant: Vera Dorosh Sebulsky Submissions to The Carl Beck Papers are welcome. Manuscripts must be in English, double-spaced throughout, and between 40 and 90 pages in length. Acceptance is based on anonymous review. Mail submissions to: Editor, The Carl Beck Papers, Center for Russian and East European Studies, 4400 Wesley W. Posvar Hall, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260. -

The Panama Canal Review Is Published Twice a Year

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES m.• #.«, I i PANAMA w^ p IE I -.a. '. ±*L. (Qfx m Uu *£*£ - Willie K Friar David S. Parker Editor, English Edition Governor-President Jose T. Tunon Charles I. McGinnis Editor, Spanish Edition Lieutenant Governor Writers Eunice Richard, Frank A. Baldwin Fannie P. Hernandez, Publication Franklin Castrellon and Dolores E. Suisman Panama Canal Information Officer Official Panama Canal the Review will be appreciated. Review articles may be reprinted without further clearance. Credit tu regular mail airmail $2, single copies 50 cents. The Panama Canal Review is published twice a year. Yearly subscription: $1, Canal Company, to Panama Canal Review, Box M, Balboa Heights, C.Z. For subscription, send check or money order, made payable to the Panama Editorial Office is located in Room 100, Administration Building, Balboa Heights, C.Z. Printed at the Panama Canal Printing Plant, La Boca, C.Z. Contents Our Cover The Golden Huacas of Panama 3 Huaca fanciers will find their favor- the symbolic characters of Treasures of a forgotten ites among the warrior, rainbow, condor god, eagle people arouse the curiosity and alligator in this display of Pan- archeologists around the of ama's famous golden artifacts. world. The huacas, copied from those recov- Snoopy Speaks Spanish 8 ered from the graves of pre-Columbian loaned to The In the phonetics of the fun- Carib Indians, were Review by Neville Harte. The well nies, a Spanish-speaking dog known local archeologist also provided doesn't say "bow wow." much of the information for the article Balseria 11 from his unrivaled knowledge of the Broken legs are the name of subject—the fruit of a 26-year-long love affair with the huaca, and the country the game when the Guaymis and people of Panama, past and present. -

White, Women and the World of Ballet

White, women and the world of ballet Greek fashion, muslin The ballet paintings, drawings and sculptures Muslin was washable and it fell gracefully like the cloth and combustible of the French artist Edgar Degas are known to us all. folds of the costumes on the Greek statues that ballerinas – Michelle His dancers are captured in the studio, in the wings, were unearthed when the ruins of the ancient city Potter takes you backstage, on stage. We see them resting, practising, of Pompeii were excavated. White clothing also through the history of taking class, performing. They are shown from many indicated status. A white garment was hard to keep the innocent white tutu angles: from the orchestra pit, from boxes, as long clean so the well-dressed woman in a pristine white shots, as close-ups. They wear a soft skirt reaching outfit was clearly rich enough to have many dresses just below the knee. It has layers of fabric pushing in her wardrobe. Since ballet costuming at the time it out into a bell shape and often there is a sash followed fashion trends, white also became the at the waist, which is tied in a bow at the back. colour of the new, free-flowing ballet dresses. Most of his dancers also wear a signature band Soon the white, Greek-inspired dress had given of ribbon at the neck. The dress has a low cut bodice way to the long, white Romantic costume as worn with, occasionally, a short, frilled sleeve. More often by the Sylphide and her attendants in La Sylphide. -

Gp 3.Qxt 7/14/17 2:07 PM Page 1 Page 4

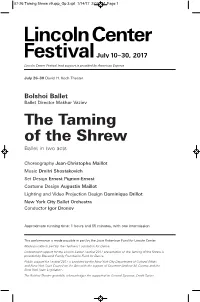

07-26 Taming Shrew v9.qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/14/17 2:07 PM Page 1 Page 4 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 26–30 David H. Koch Theater Bolshoi Ballet Ballet Director Makhar Vaziev The Taming of the Shrew Ballet in two acts Choreography Jean-Christophe Maillot Music Dmitri Shostakovich Set Design Ernest Pignon-Ernest Costume Design Augustin Maillot Lighting and Video Projection Design Dominique Drillot New York City Ballet Orchestra Conductor Igor Dronov Approximate running time: 1 hours and 55 minutes, with one intermission This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Made possible in part by The Harkness Foundation for Dance. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2017 presentation of The Taming of the Shrew is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. Public support for Festival 2017 is provided by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. The Bolshoi Theatre gratefully acknowledges the support of its General Sponsor, Credit Suisse. 07-26 Taming Shrew.qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/18/17 12:10 PM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2017 THE TAMING OF THE SHREW Wednesday, July 26, 2017, at 7:30 p.m. The Taming of the Shrew Katharina: Ekaterina Krysanova Petruchio: Vladislav Lantratov Bianca: Olga Smirnova Lucentio: Semyon Chudin Hortensio: Igor Tsvirko Gremio: Vyacheslav Lopatin The Widow: Yulia Grebenshchikova Baptista: Artemy Belyakov The Housekeeper: Yanina Parienko Grumio: Georgy Gusev MAIDSERVANTS Ana Turazashvili, Daria Bochkova, Anastasia Gubanova, Victoria Litvinova, Angelina Karpova, Daria Khokhlova SERVANTS Alexei Matrakhov, Dmitry Dorokhov, Batyr Annadurdyev, Dmitri Zhuk, Maxim Surov, Anton Savichev There will be one intermission.