Litigation & Dispute Resolution 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Experience of the French Civil Code

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 20 Number 2 Article 3 Winter 1995 Codes as Straight-Jackets, Safeguards, and Alibis: The Experience of the French Civil Code Oliver Moreleau Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Oliver Moreleau, Codes as Straight-Jackets, Safeguards, and Alibis: The Experience of the French Civil Code, 20 N.C. J. INT'L L. 273 (1994). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol20/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Codes as Straight-Jackets, Safeguards, and Alibis: The Experience of the French Civil Code Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This article is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol20/ iss2/3 Codes as Straight-Jackets, Safeguards, and Alibis: The Experience of the French Civil Code Olivier Moriteaut I. Introduction: The Civil Code as a Straight-Jacket? Since 1789, which marked the year of the French Revolution, France has known no fewer than thirteen constitutions.' This fact is scarcely evidence of political stability, although it is fair to say that the Constitution of 1958, of the Fifth Republic, has remained in force for over thirty-five years. On the other hand, the Civil Code (Code), which came into force in 1804, has remained substantially unchanged throughout this entire period. -

Use the Force? Understanding Force Majeure Clauses

Use the Force? Understanding Force Majeure Clauses J. Hunter Robinson† J. Christopher Selman†† Whitt Steineker††† Alexander G. Thrasher†††† Introduction It has been said that, sooner or later, everything old is new again.1 In the wake of the novel coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) sweeping the globe in 2020, a heretofore largely overlooked and even less understood nineteenth century legal term has come to the forefront of American jurisprudence: force majeure. Force majeure has become a topic du jour in the COVID-19 world with individuals and companies around the world seeking to excuse non- † B.S. (2011), Auburn University; J.D. (2014), Emory University School of Law. Hunter Robinson is an associate at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Hunter is a member of the firm’s litigation and banking and financial services practice groups and represents clients in commercial litigation matters across the country. †† B.S. (2007), Auburn University; J.D. (2012), University of South Carolina School of Law. Chris Selman is a partner at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Chris is a members of the firm’s construction and government contracts practice group. He has extensive experience advising clients at every stage of a construction project, managing the resolution of construction disputes domestically and internationally, and drafting and negotiating contracts for a variety of contractor and owner clients. ††† B.A. (2003), University of Alabama; J.D. (2008), Georgetown University Law Center. Whitt Steineker is a partner at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Whitt is a member of the firm’s litigation practice group, where he advises clients on a full range of services and routinely represents companies in complex commercial litigation. -

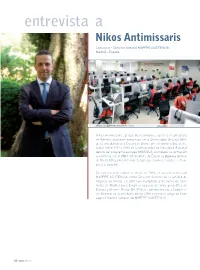

Interview With

entrevista a Nikos Antimissaris Consejero – Director General MAPFRE ASISTENCIA Madrid – España Contact center de MAPFRE ASISTENCIA en China Nikos Antimissaris, griego de nacimiento, cursó la Licenciatura en Administración de Empresas en la Universidad de Lieja (Bél- gica), vinculándose a España el último año de universidad, al es- tudiar entre 1992 y 1993 en la Universidad de Valladolid (España) dentro del programa europeo ERASMUS. Completó su formación académica con el MBA del Instituto de Empresa Business School, de Madrid (España). Además del griego, domina el inglés, el fran- cés y el español. Su carrera profesional se inició en 1994 en su país natal con MAPFRE ASISTENCIA, como Director General de la Unidad de Negocio de Grecia. En 2001 fue trasladado a los Servicios Cen- trales en Madrid para dirigir el negocio del área geográfica de Europa y Oriente Medio. En 2004 fue promocionado a Subdirec- tor General de la entidad y desde 2006 ostenta el cargo de Con- sejero Director General de MAPFRE ASISTENCIA. 40 / 67 / 2013 667_trebol_esp.indd7_trebol_esp.indd 4040 007/11/137/11/13 001:581:58 “MAPFRE ASISTENCIA aporta una solución integral a sus socios aseguradores que incluye, no sólo la suscripción del riesgo (por la vía del reaseguro), sino también toda la infraestructura operativa para la tramitación de los siniestros y la prestación de los servicios.” Nikos Antimissaris habla siempre en primera persona del plural porque siente que alcanzar en 2013 un volumen de ingresos de mil cien millones de euros es una labor de los seis mil empleados de MAPFRE ASISTENCIA desde los cuarenta y cinco países en que está presente. -

Is COVID-19 an Act of God And/Or Will COVID-19 Be a Defense Against Failure to Perform? Swata Gandhi

ALERT Corporate Practice MAY 2020 Is COVID-19 an Act of God and/or Will COVID-19 Be a Defense Against Failure to Perform? Swata Gandhi This is the second in a series of alerts on Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses against failure to perform contracts. In our first alert, we discussed the elements of a force majeure clause and looked at how various states have interpreted force majeure clauses. We focused on how most states take a narrow view of these provisions and they adhere to the plain meaning of the force majeure provisions. This alert takes a look at one event often listed in force majeure clauses – Acts of God. As discussed in our previous alert, some courts will excuse performance of a contract only if the event causing the breach is actually listed in the force majeure clause. Among the list of events that would most likely excuse a failure to perform under a contract due to COVID-19 would be if the force majeure provision listed pandemics, epidemic, health emergencies or government orders or regulations. While your contract may not list these events, most force majeure provisions do include an Act of God. In this alert we look at whether it is likely that courts will find that COVID-19 is an Act of God and if such consideration will actually be a defense against performance of a contract. In general, courts have found that an Act of God is a natural event that would not occur by the intervention of man, but proceeds from physical causes. -

A Force Majeure Event?

COVID-19: A FORCE MAJEURE EVENT? Following the outbreak of the novel coronavirus and the consequential surveillance and controls introduced by a number of governments including the Luxembourg government, it may become essential to determine whether these events may be considered as force majeure events under Luxembourg law. Following the outbreak of the novel coronavirus, one question arising with regard to contracts is whether this outbreak and its consequences, especially also taking into account the measures taken by different governments, including amongst others confinement measures, closure of the borders, possible closure of companies, etc. - may be considered as a force majeure event. This may be envisaged from two perspectives. Firstly, there may be a force majeure clause in a given agreement. Such a clause is normally used to describe a contractual term by which one or both of the parties is entitled to suspend performance of its affected obligations or to claim an extension of time for performance, following a specified event or events beyond its control. It may also entitle termination of the contract, usually if it exceeds a specified duration. Whether or not the outbreak of the novel coronavirus will constitute force majeure in a contract is very much a case of interpretation of the relevant wording in the contract, and such clauses would need to be analysed in detail. Secondly, according to general Luxembourg civil law principles, a force majeure event may be raised by a party responsible of having breached its contractual obligations in order to be discharged from its liability. According to Luxembourg case law, a force majeure event has to be (i) external to the liable party, (ii) unpredictable and (iii) irresistible. -

Force Majeure and Climate Change: What Is the New Normal?

Force majeure and Climate Change: What is the new normal? Jocelyn L. Knoll and Shannon L. Bjorklund1 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................2 I. THE SCIENCE OF CLIMATE CHANGE ..................................................................................4 II. FORCE MAJEURE: HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT .........................................................8 III. FORCE MAJEURE IN CONTRACTS ...................................................................................11 A. Defining the Force Majeure Event. ..............................................................................12 B. Additional Contractual Requirements: External Causation, Unavoidability and Notice 15 C. Judicially-Imposed Requirements. ...............................................................................18 1. Foreseeability. .................................................................................................18 2. Ultimate (or external) causation.....................................................................21 D. The Effect of Successfully Invoking a Contractual Force Majeure Provision ............25 E. Force Majeure in the Absence of a Specific Contractual Provision. ...........................25 IV. FORCE MAJEURE PROVISIONS IN STANDARD FORM CONTRACTS AND MANDATORY PROVISIONS FOR GOVERNMENT CONTRACTS ......................................28 A. Standard Form Contracts .............................................................................................28 -

Consent Decree: United States Of

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA ATLANTA DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) Civil Action No. 1:00-CV-3142 JTC v. ) ) CONSENT DECREE COLONIAL PIPELINE COMPANY, ) ) Defendant. ) ____________________________________) I. BACKGROUND A. Plaintiff, the United States of America (“United States”), through the Attorney General, at the request of the Administrator of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”), filed a civil complaint (“Complaint”) against Defendant, Colonial Pipeline Company (“Colonial”), pursuant to the Clean Water Act (“CWA”), 33 U.S.C. §§ 1251 et seq., seeking injunctive relief and civil penalties for the discharge of oil into navigable waters of the United States or onto adjoining shorelines. B. The Parties agree that it is desirable to resolve the claims for civil penalties and injunctive relief asserted in the Complaint without further litigation. C. This Consent Decree is entered into between the United States and Colonial for the purpose of settlement and it does not constitute an admission or finding of any violation of federal or state law. This Decree may not be used in any civil proceeding of any type as evidence or proof of any fact or as evidence of the violation of any law, rule, regulation, or Court decision, except in a proceeding to enforce the provisions of this Decree. D. To resolve Colonial’s civil liability for the claims asserted in the Complaint, Colonial will pay a total civil penalty of $34 million to the United States, comply with the injunctive relief requirements in this Consent Decree, and satisfy all other terms of this Consent Decree. -

Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses | a National Survey | Shook, Hardy & Bacon

2020 — Force Majeure SHOOK SHB.COM and Common Law Defenses A National Survey APRIL 2020 — Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses A National Survey Contractual force majeure provisions allocate risk of nonperformance due to events beyond the parties’ control. The occurrence of a force majeure event is akin to an affirmative defense to one’s obligations. This survey identifies issues to consider in light of controlling state law. Then we summarize the relevant law of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. 2020 — Shook Force Majeure Amy Cho Thomas J. Partner Dammrich, II 312.704.7744 Partner Task Force [email protected] 312.704.7721 [email protected] Bill Martucci Lynn Murray Dave Schoenfeld Tom Sullivan Norma Bennett Partner Partner Partner Partner Of Counsel 202.639.5640 312.704.7766 312.704.7723 215.575.3130 713.546.5649 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SHOOK SHB.COM Melissa Sonali Jeanne Janchar Kali Backer Erin Bolden Nott Davis Gunawardhana Of Counsel Associate Associate Of Counsel Of Counsel 816.559.2170 303.285.5303 312.704.7716 617.531.1673 202.639.5643 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] John Constance Bria Davis Erika Dirk Emily Pedersen Lischen Reeves Associate Associate Associate Associate Associate 816.559.2017 816.559.0397 312.704.7768 816.559.2662 816.559.2056 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Katelyn Romeo Jon Studer Ever Tápia Matt Williams Associate Associate Vergara Associate 215.575.3114 312.704.7736 Associate 415.544.1932 [email protected] [email protected] 816.559.2946 [email protected] [email protected] ATLANTA | BOSTON | CHICAGO | DENVER | HOUSTON | KANSAS CITY | LONDON | LOS ANGELES MIAMI | ORANGE COUNTY | PHILADELPHIA | SAN FRANCISCO | SEATTLE | TAMPA | WASHINGTON, D.C. -

COVID-19: Force Majeure and Contract Considerations for Buyers and Sellers

COVID-19: Force Majeure and Contract Considerations for Buyers and Sellers On March 18, 2020, Robinson+Cole’s Taylor Shea and Jeff White participated in the Coronavirus Special Topics Conference Call hosted by the U.S. Department of Commerce. An overview of their presentation is below. FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS CHECKLIST What is a force majeure provision? If you are making a force majeure claim: + A force majeure provision is a clause in a contract that generally + Confirm that you have the right to claim a excuses a party for non-performance under a contract if the non- force majeure event has occurred under your performance is caused by an event that is outside the reasonable contract. control of the affected party. + Carefully consider what force majeure event What if my contract does not contain a force majeure provision? you will declare and how it is framed. + Typically, force majeure provisions are not read into contracts; + Be mindful of your mitigation obligations, and they must be expressly stated in a contract for an affected party document all of them. to be able to invoke. If your contract is silent, there may be other remedies an affected party can pursue (e.g., under the Uniform + Make sure you deliver notices in compliance Commercial Code or the common law). with your contract. Where is a force majeure provision found in a contract? + Do not favor one customer over another. + It can be anywhere, but will typically be found in the “boilerplate” If you receive a force majeure notice claim: language of a contract – which is basically the legal jargon at the + Confirm that the other party has a right to claim end of agreement. -

Application of Force Majeure Under English Law, New York Law and Russian Law (Comparative Analysis)

Application of Force Majeure under English Law, New York Law and Russian Law (Comparative Analysis) April 29, 2020 The current COVID-19 pandemic has, among other issues, highlighted the role of force majeure in commercial contracts. Whether contractual parties are able to rely on the concept of force majeure as grounds to suspend performance of their respective obligations where the performance of relevant obligations has been impeded by a force majeure event, i.e. an unexpected event outside the parties' control (like the COVID-19 outbreak and related governmental emergency measures), will depend on the applicable law and relevant contract provision. In the table below we have briefly commented on the main questions related to application of force majeure under English, New York and Russian law, taking into account the existing COVID-19 situation. Austin Beijing Brussels Dallas Dubai Hong Kong Houston London Moscow New York Palo Alto Riyadh San Francisco Washington bakerbotts.com | Confidential | Copyright© 2020 Baker Botts L.L.P. No. Position under English Law Position under NY Law Position under Russian Law 1. May a party refer to a force majeure event as grounds to suspend performance / be exempt from liability for non- performance if the contract does not contain a force majeure clause? No. No. Generally, yes. There is no independent concept of Under NY law, the presence of an Russian law contains a general statutory rule that a force majeure under English law. A express force majeure clause covering party to a commercial contract may be released from party may only rely on force majeure relevant events in a contract is a liability for non-performance of its obligations if it if it is expressly provided for in a prerequisite for any claim of force proves that performance was impossible due to a contract. -

Construction Law Journal

Construction Law Journal Summer 2021 Volume 17, Number 1 IN THIS ISSUE: ENGINEERING, PROCUREMENT, AND CONSTRUCTION CONTRACTS IN TEXAS: KEY PROVISIONS, ISSUES, AND PITFALLS THE FORCE MAJEURE DOCTRINE AND STANDARD CONSTRUCTION FORM CONTRACT PROVISIONS: REVISITING AN OLD CONTRACT PROVISION DURING THESE NEW UNCERTAIN TIMES FREEDOM OF CONTRACT AND ITS LIMITS: SELECTED ISSUES FOR THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY CONSTRUCTION AHEAD, EXPECT DELAYS ON GOVERNMENTAL IMMUNITY Official Publication of the Construction Law Section of the State Bar of Texas • www.constructionlawsection.org CONSTRUCTION LAW JOURNAL BY: MATTHEW S.C. MOORE AND CORNELIUS F. "LEE" BANTA, JR.1 THE FORCE MAJEURE DOCTRINE AND STANDARD CONSTRUCTION FORM CONTRACT PROVISIONS: REVISITING AN OLD CONTRACT PROVISION DURING THESE NEW UNCERTAIN TIMES I. INTRODUCTION Committee (EJCDC), and Design-Build Institute of America (DBIA) through a COVID-19 lens and propose As we approach the first anniversary of the World Health modifications to balance the risks and exposures caused by Organization’s declaration of COVID-19 as a global COVID-19 or other pandemics. pandemic, its impact on local and global economies and our way of life cannot be ignored. The effects of COVID-19 to II. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND the construction industry are wide-reaching. Consequences The force majeure doctrine has its historical underpinnings on a project site include quarantines or other governmental in the British common law doctrine associated with restrictions resulting in impacts to the project workforce. frustration of purpose and impossibility of performance.2 Offsite impacts can cover a much broader scope of As one may recall from their 1L Contracts class, early issues implicating the various links of the supply chain British common law imposed absolute liability on parties relied upon by the construction industry. -

Force Majeure Clauses in Contracts and Business Interruption Insurance1 2 3

Chicago-Area Small Business Information on COVID-19: Force Majeure Clauses in Contracts and Business Interruption Insurance1 2 3 Businesses across the Chicago area have had their normal operations disrupted by the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic. Illinois is just one of many states that has issued a “stay at home” order, forcing all “non-essential” businesses to close their physical offices.4 While some businesses have been able to continue operating with their employees working remotely, others have been forced to completely or partially suspend operations. The current situation has made it difficult, if not impossible, for many small businesses to meet all of their contractual obligations. This has led some business owners to question whether the COVID-19 pandemic can legally excuse them from performing under these contracts, either temporarily or permanently. This is a complicated legal question with no easy answers, but this handout is intended to serve as a guide to what are known as “force majeure” clauses in contracts. This handout will also briefly discuss whether the COVID-19 pandemic is covered under commonly-held business interruption insurance policies. I. What is Force Majeure? Force majeure is a French term that translates as “superior force.” In the context of contract law, a force majeure clause is a contractually defined event, beyond the control of both parties, which prevents a party from performing under the contract and legally excuses their obligation to perform.5 Depending on the language of the contract and the specific event, a party can be temporarily or permanently excused from performing. Some laypeople colloquially refer to these clauses as “Act of God” provisions.