90004273.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Carillon Music

Tower Inside the Singing Tower Clock Music DAILY CARILLON MUSIC Architect: Milton B. Medary (Philadelphia) Announcing the hour strike: March 14-17, 2019 Lake Wales Nocturne (excerpt) Purpose: To house the carillon; serve as a Johan Franco centerpiece for the Gardens; the private Carillon Concerts at 1:00 and 3:00 p.m. use of the Bok family 9:00 Prelude Johann Sebastian Bach Built: 1927-1929 7 9:30 Sarabande (for carillon) Benoit Franssen Height: 205 feet (62.5 meters) 10:00 Somber Pavane (for carillon) Ronald Barnes Weight: 5,500 tons (5,000 metric tons) 6 10:30 Andante Joseph H. Fiocco Structure: Steel frame with brick walls; outer facing 5 of pink and gray Georgia marble and 11:00 Spring Morning (for carillon) Geert D’hollander Florida coquina, a limestone of shell and 4 coral fragments Sorrowing Foundation: 118 reinforced concrete piles, 13-24 feet 11:30 Andante (for carillon) Ronald Barnes (4-7 meters) underground with a concrete 3 cap of 2.5 feet (0.8 meter) 12:00 Prelude VI (for carillon) Matthias vanden Gheyn Sculpture: Lee Lawrie (New York City); herons at the top, eagles at the base of the bellchamber; 12:30 Chaconne * Auguste Durant all sculptures were carved on-site CONCERT Colorful Grilles near the top: 1:00 Ceramic tiles designed by J.H. Dulles 2 Allen (Philadelphia) 2:00 Dreaming (for carillon) Geert D’hollander Brass Door and Wrought-iron Gates with Birds: 1 2:30 Andante (for carillon) Ioannes de Gruijtters Samuel Yellin (Philadelphia); depicts the Biblical story of Creation 3:00 CONCERT 1. -

Explanation Generation in a Kabuki Dance Stage Performing Structure Simulation System

2020 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI) Explanation Generation in a Kabuki Dance Stage Performing Structure Simulation System Miku Kawai Jumpei Ono Takashi Ogata Faculty of Software and Information Science Faculty of Software and Information Technology Faculty of Software and Information Science Iwate Prefectural University Aomori University Iwate Prefectural University Takizawa, Iwate, Japan Edogawa City, Tokyo, Japan Takizawa, Iwate, Japan [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—We are developing a stage performing structure The information collected was divided into two types: general simulation system. This paper introduces the generation of information and unique information on Kyōganoko Musume explanations into the system. First, we classified the explanations Dōjōji. For example, the term “Dōjōji” requires a general we collected. Thereafter, we prototyped a mechanism wherein the explanation of the building called Dōjōji, as well as an system automatically determines the content and method of an explanation of “Dōjōji” in the story. We obtained a general explanation based on arbitrary parameters. Through this trial, we explanation from Wikipedia and created a unique explanation will examine effective explanation methods for story generation. using [9]. Keywords— Dōjōji, Explanation, Stage Performing Structure, We used three types of explanations: general explanations, unique explanations, and unchiku explanations. The system has I. INTRODUCTION interest information, frequency information, and knowledge In an existing paper [1], the explanation of technical terms amount information. Interest information indicates how has been discussed. Another study has explained the problem- interested a user is in an item. Frequency information indicates solving process of AI systems [2]. -

A History of Kane County, Utah Centennial County History Series

A HISTORY OF <Kam County Martha Sonntag Bradley UTAH CENTENNIAL COUNTY HISTORY SERIES A HISTORY OF County Martha Sonntag Bradley Kane County is noted for some of the most beautiful—though often inhospitable—land in Utah and has been home to resourceful humans for thousands of years. It was outside the area of first Mormon settlement and was actually created in the early 1860s before many had moved to the area. After the Black Hawk War, settlers soon moved to favorable locations such as Kanab and Long Valley, establishing towns in the isolated region north of the Arizona Strip with economies based on ranching and timber harvesting. With the improvement of area roads and communications in the twentieth century, more people became aware of the scenic splen dor of the county, and tourism and movie making began to increase, Kanab even be coming known as Utah's Little Hollywood during the heyday of filmmaking. Traditional extractive uses of the land's resources have declined in recent years, but the recent cre ation of the Grand Staircase-Escalante Na tional Monument has brought the promise of increased tourism to the area. It also has sparked opposition from many who had hoped for coal mining development in the region. Issues of control and uses of public lands promise to be debated vigorously as the county enters the new millenium. ISBN: 0-913738-40-9 A HISTORY OF cKgne County A HISTORY OF JOme County Martha Sonntag Bradley 1999 Utah State Historical Society Kane County Commission Copyright © 1999 by Kane County Commission All rights -

(EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli

FAMILY (EN) GROUP (EN) KEYWORD (EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli Wind Accordions Accordion Strings Zithers Accord‐zither Percussion Drums Adufe Strings Musical bows Adungu Strings Zithers Aeolian harp Keyboard Organs Aeolian organ Wind Others Aerophone Percussion Bells Agogo Ogebe ; Ugebe Percussion Drums Agual Agwal Wind Trumpets Agwara Wind Oboes Alboka Albogon ; Albogue Wind Oboes Algaita Wind Flutes Algoja Algoza Wind Trumpets Alphorn Alpenhorn Wind Saxhorns Althorn Wind Saxhorns Alto bugle Wind Clarinets Alto clarinet Wind Oboes Alto crumhorn Wind Bassoons Alto dulcian Wind Bassoons Alto fagotto Wind Flugelhorns Alto flugelhorn Tenor horn Wind Flutes Alto flute Wind Saxhorns Alto horn Wind Bugles Alto keyed bugle Wind Ophicleides Alto ophicleide Wind Oboes Alto rothophone Wind Saxhorns Alto saxhorn Wind Saxophones Alto saxophone Wind Tubas Alto saxotromba Wind Oboes Alto shawm Wind Trombones Alto trombone Wind Trumpets Amakondere Percussion Bells Ambassa Wind Flutes Anata Tarca ; Tarka ; Taruma ; Turum Strings Lutes Angel lute Angelica Percussion Rattles Angklung Mechanical Mechanical Antiphonel Wind Saxhorns Antoniophone Percussion Metallophones / Steeldrums Anvil Percussion Rattles Anzona Percussion Bells Aporo Strings Zithers Appalchian dulcimer Strings Citterns Arch harp‐lute Strings Harps Arched harp Strings Citterns Archcittern Strings Lutes Archlute Strings Harps Ardin Wind Clarinets Arghul Argul ; Arghoul Strings Zithers Armandine Strings Zithers Arpanetta Strings Violoncellos Arpeggione Keyboard -

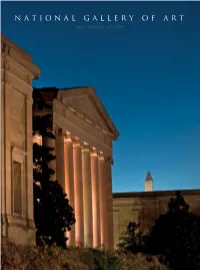

NGA | 2012 Annual Report

NA TIO NAL G AL LER Y O F A R T 2012 ANNUAL REPort 1 ART & EDUCATION Diana Bracco BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE Vincent J. Buonanno (as of 30 September 2012) Victoria P. Sant W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Chairman Calvin Cafritz Earl A. Powell III Leo A. Daly III Frederick W. Beinecke Barney A. Ebsworth Mitchell P. Rales Gregory W. Fazakerley Sharon P. Rockefeller Doris Fisher John Wilmerding Juliet C. Folger Marina Kellen French FINANCE COMMITTEE Morton Funger Mitchell P. Rales Lenore Greenberg Chairman Frederic C. Hamilton Timothy F. Geithner Richard C. Hedreen Secretary of the Treasury Teresa Heinz Frederick W. Beinecke John Wilmerding Victoria P. Sant Helen Henderson Sharon P. Rockefeller Chairman President Benjamin R. Jacobs Victoria P. Sant Sheila C. Johnson John Wilmerding Betsy K. Karel Linda H. Kaufman AUDIT COMMITTEE Robert L. Kirk Frederick W. Beinecke Leonard A. Lauder Chairman LaSalle D. Leffall Jr. Timothy F. Geithner Secretary of the Treasury Edward J. Mathias Mitchell P. Rales Diane A. Nixon John G. Pappajohn Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Mitchell P. Rales Victoria P. Sant Sally E. Pingree John Wilmerding Diana C. Prince Robert M. Rosenthal TRUSTEES EMERITI Roger W. Sant Robert F. Erburu Andrew M. Saul John C. Fontaine Thomas A. Saunders III Julian Ganz, Jr. Fern M. Schad Alexander M. Laughlin Albert H. Small David O. Maxwell Michelle Smith Ruth Carter Stevenson Benjamin F. Stapleton Luther M. Stovall Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Roberts Jr. EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Ladislaus von Hoffmann Chief Justice of the Diana Walker United States Victoria P. Sant President Alice L. -

Sing! 1975 – 2014 Song Index

Sing! 1975 – 2014 song index Song Title Composer/s Publication Year/s First line of song 24 Robbers Peter Butler 1993 Not last night but the night before ... 59th St. Bridge Song [Feelin' Groovy], The Paul Simon 1977, 1985 Slow down, you move too fast, you got to make the morning last … A Beautiful Morning Felix Cavaliere & Eddie Brigati 2010 It's a beautiful morning… A Canine Christmas Concerto Traditional/May Kay Beall 2009 On the first day of Christmas my true love gave to me… A Long Straight Line G Porter & T Curtan 2006 Jack put down his lister shears to join the welders and engineers A New Day is Dawning James Masden 2012 The first rays of sun touch the ocean, the golden rays of sun touch the sea. A Wallaby in My Garden Matthew Hindson 2007 There's a wallaby in my garden… A Whole New World (Aladdin's Theme) Words by Tim Rice & music by Alan Menken 2006 I can show you the world. A Wombat on a Surfboard Louise Perdana 2014 I was sitting on the beach one day when I saw a funny figure heading my way. A.E.I.O.U. Brian Fitzgerald, additional words by Lorraine Milne 1990 I can't make my mind up- I don't know what to do. Aba Daba Honeymoon Arthur Fields & Walter Donaldson 2000 "Aba daba ... -" said the chimpie to the monk. ABC Freddie Perren, Alphonso Mizell, Berry Gordy & Deke Richards 2003 You went to school to learn girl, things you never, never knew before. Abiyoyo Traditional Bantu 1994 Abiyoyo .. -

Features by Shannon Norton Richards

No. 100 November 2018 www.gcna.org Newsletter of the Guild of Carillonneurs in North America 2018 Congress Report Features by Shannon Norton Richards he 76th Congress of The Guild of TCarillonneurs in North America was 2018 Congress graciously hosted by the Springfield Park Report 1 District, The Carillon Belles, and The Rees Carillon Society on June 4-8, 2018, at the From the President's Thomas Rees Memorial Carillon in Spring- Corner 3 field, Illinois. The 57th International Caril- lon Festival, held concurrently on June 3-8, Festivals and featured two artist carillon recitals plus other Symposia 5 performances of local musicians each eve- ning. Congress attendees received two pro- Towers and gram books: the Congress and the Festival. Excursions 10 The front cover carillon art (same image for both programs and the Congress tote bag) was done in pastels by local artist, Tracey Plus Maras, who created other beautiful carillon art for previous Springfield International Calendar 3 Carillon Festivals. Take Notes: The Thomas Rees Memorial Carillon, a Awards, Exams, 67-bell Petit and Fritsen instrument built Education 7 in 1962 and enlarged in 2000, is located in Washington Park. Senator Thomas Rees Reviews 9 (1850-1933), whose interest was piqued In Memoriam 14 from William Gorham Rice's writings and enhanced by visits to The Netherlands and Belgium, gifted the carillon to the city of Springfield. Throughout this carillon's his- tory, many Springfield citizens have and continue to support this beloved treasure. On Sunday evening, preceding the Congress, The Thomas Rees Memorial Carillon continues on page 3 1 Carillon NEWS Board Members and Officers: Carillon News is published each April and No- Julianne Vanden Wyngaard, President vember by the Guild of Carillonneurs in North [email protected] America, a California non-profit corporation. -

Sacred Music Volume 122 Number 4

Santa Barbara, California SACRED MUSIC Volume 122, Number 4, Winter 1995 FROM THE EDITORS 3 Publishers A Parish Music Program CREATIVITY AND THE LITURGY 6 Kurt Poterack SURVEY OF THE HISTORY OF CAMPANOLOGY IN THE WESTERN 7 CHRISTIAN CULTURAL TRADITION Richard J. Siegel GREGORIAN CHANT, AN INSIDER'S VIEW: MUSIC OF HOLY WEEK 21 Mother M. Felicitas, O.S.B. MUSICAL MONSIGNORI OR MILORDS OF MUSIC HONORED BY THE POPE. PART II 27 Duane L.C.M. Galles REVIEWS 36 NEWS 40 EDITORIAL NOTES 41 CONTRIBUTORS 41 INDEX OF VOLUME 122 42 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of Publication: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103. Editorial Board: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler, Editor Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Rev. John Buchanan Harold Hughesdon William P. Mahrt Virginia A. Schubert Cal Stepan Rev. Richard M. Hogan Mary Ellen Strapp News: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 Music for Review: Paul Salamunovich, 10828 Valley Spring Lane, N. Hollywood, Calif. 91602 Paul Manz, 1700 E. 56th St., Chicago, Illinois 60637 Membership, Circulation and Advertising: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Monsignor Richard J. Schuler Vice-President Gerhard Track General Secretary Virginia A. Schubert Treasurer Donna Welton Directors Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Mrs. Donald G. Vellek William P. -

Namertrad.Pdf

| ============================================================== | ============================================================== | | | | | | TERMS OF USE | | | | | CARILLONS OF THE WORLD | The PDF files which constitute the online edition of this | | --------- -- --- ----- | publication are subject to the following terms of use: | | | (1) Only the copy of each file which is resident on the | | | GCNA Website is sharable. That copy is subject to revision | | Privately published on behalf of the | at any time without prior notice to anyone. | | World Carillon Federation and its member societies | (2) A visitor to the GCNA Website may download any of the | | | available PDF files to that individual's personal computer | | by | via a Web browser solely for viewing and optionally for | | | printing at most one copy of each page. | | Carl Scott Zimmerman | (3) A file copy so downloaded may not be further repro- | | Chairman of the former | duced or distributed in any manner, except as incidental to | | Special Committee on Tower and Carillon Statistics, | the course of regularly scheduled backups of the disk on | | The Guild of Carillonneurs in North America | which it temporarily resides. In particular, it may not be | | | subject to file sharing over a network. | | ------------------------------------------------------- | (4) A print copy so made may not be further reproduced. | | | | | Online Edition (a set of Portable Document Format files) | | | | CONTENTS | | Copyright November 2007 by Carl Scott Zimmerman | | | | The main purpose of this publication is to identify and | | All rights reserved. No part of this publication may | describe all of the traditional carillons in the world. But | | be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans- | it also covers electrified carillons, chimes, rings, zvons | | mitted, in any form other than its original, or by any | and other instruments or collections of 8 or more tower bells | | means (electronic, photographic, xerographic, recording | (even if not in a tower), and other significant tower bells. -

Edward L. Shaughnessy Chinese Annals in the Western Observatory Library of Sinology

Edward L. Shaughnessy Chinese Annals in the Western Observatory Library of Sinology Editors Zhi Chen, Dirk Meyer Executive Editor Adam C. Schwartz Editorial Board Wolfgang Behr, Marc Kalinowski, Hans van Ess, Bernhard Fuehrer, Anke Hein, Clara Wing-chung Ho, Maria Khayutina, Michael Lackner, Yuri Pines, Alain Thote, Nicholas Morrow Williams Volume 4 Edward L. Shaughnessy Chinese Annals in the Western Observatory An Outline of Western Studies of Chinese Unearthed Documents The publication of the series has been supported by the HKBU Jao Tsung-I Academy of Sinology — Amway Development Fund. ISBN 978-1-5015-1693-1 e-ISBN [PDF] 978-1-5015-1694-8 e-ISBN [EPUB] 978-1-5015-1710-5 ISSN 2625-0616 This work is licensed under the Creatice Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019953355 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Shaughnessy/JAS, published by Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Dedicated to the memory of LI Xueqin 李學勤 (1933-2019) 南山有杞,北山有李。 樂只君子,德音不已。 On South Mountain is a willow, On North Mountain is a plum tree. Such joy has the noble-man brought, Sounds of virtue never ending. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES | XI PREFACE TO THE CHINESE EDITION | -

THE SHAMANIC and ESOTERIC ORIGINS of the JAPANESE MARTIAL ARTS Tengu and a Buddhist Monk, by Kawanabe Kyo¯ Sai

TENGU THE SHAMANIC AND ESOTERIC ORIGINS OF THE JAPANESE MARTIAL ARTS Tengu and a Buddhist monk, by Kawanabe Kyo¯ sai. The tengu wears the cap and pom-pommed sash of a follower of Shugendo¯ . Now is the time to show the world those arts of war that I have rehearsed for many months and years upon the Mountain of Kurama _________ Words spoken by the Chorus in the No play ‘Eboshi-ori’ by Miyamasu (sixteenth century) They refer to the tengu training given to Ushiwaka Who later became the famous young general, Minamoto-no-Yoshitsune T E N G U The Shamanic and Esoteric Origins of the Japanese Martial Arts By ROALD KNUTSEN TENGU The Shamanic and Esoteric Origins of the Japanese Martial Arts By Roald Knutsen First published 2011 by GLOBAL ORIENTAL PO Box 219 Folkestone Kent CT20 2WP UK Global Oriental is an imprint of Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints BRILL, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. www.brill.nl/globaloriental © Roald Knutsen 2011 ISBN 978-1-906876-24-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Set in Bembo 11 on 12 by Dataworks, Chennai, India Printed and bound in England by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, Wilts This book is dedicated to Patricia for always being with me Contents Plate section facing page 132 Foreword xi List of Figures xix List of Plates xxii List of Maps xxiv 1. -

0352.1.00.Pdf

helicography Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-profit press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afloat. Contri- butions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t find a welcoming port elsewhere. Our ad- venture is not possible without your support. Vive la Open Access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) helicography. Copyright © 2021 by Craig Dworkin. This work carries a Cre- ative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and trans- formation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http://creative- commons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2021 by dead letter office, babel Working Group, an imprint of punctum books, Earth, Milky Way. https://punctumbooks.com The babel Working Group is a collective and desiring-assemblage of scholar– gypsies with no leaders or followers, no top and no bottom, and only a middle.