William Perkins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Society: Explain the … Labor Force--Indentured Servants and Slaves Among the 13 Colonies

ENGLISH COLONIES IN NORTH AMERICA Date Colony Founded by Significance 1607 Jamestown Virginia Company first permanent English colony 1620 Plymouth Pilgrims Mayflower Compact 1630 Massachusetts Bay Massachusetts Bay Company Puritans 1634 Maryland Lord Baltimore first proprietary colony; only Catholic colony 1636 Rhode Island Roger Williams religious toleration 1636 Connecticut Thomas Hooker Fundamental Orders of Connecticut 1638 Delaware Sweden under English rule from 1664 1663 Carolinas proprietary North and South given separate charters in the18th century 1664 New York Duke of York under Dutch control as New Amsterdam from 1621 to 1664 1664 New Hampshire John Mason royal charter in 1679 1664 New Jersey Berkeley and Carteret overshadowed by New York 1681 Pennsylvania William Penn proprietary colony settled by Quakers 1732 Georgia James Oglethorpe buffer against Spanish Florida, debtors Economic basis of colonies: Explain … the differences between New England, the middle colonies, and the southern colonies. the role of agriculture, industry and trade among the 13 colonies. Colonial society: Explain the … labor force--indentured servants and slaves among the 13 colonies.. ethnic diversity--Germans, Scots-Irish, Jews… status of women… relations between colonists and Native Americans… religious dimensions--religious conformity vs. Religious dissent, Puritanism, First Great Awakening Relations with Great Britain Explain … mercantilism and its early impact on the colonies… the impact of events in England--Restoration (1660) and the Glorious -

Colonies with Others Puritan Colonies Were Self-Governed, with Each Town Having Its Own Government Which Led the People in Strict Accordance with Puritan Beliefs

Note Cards 1. Mayflower Compact 1620 - The first agreement for self-government in America. It was signed by the 41 men on the Mayflower and set up a government for the Plymouth colony. 2. William Bradford A Pilgrim, the second governor of the Plymouth colony, 1621-1657. He developed private land ownership and helped colonists get out of debt. He helped the colony survive droughts, crop failures, and Indian attacks. 3. Pilgrims and Puritans contrasted The Pilgrims were separatists who believed that the Church of England could not be reformed. Separatist groups were illegal in England, so the Pilgrims fled to America and settled in Plymouth. The Puritans were non-separatists who wished to adopt reforms to purify the Church of England. They received a right to settle in the Massachusetts Bay area from the King of England. 4. Massachusetts Bay Colony 1629 - King Charles gave the Puritans a right to settle and govern a colony in the Massachusetts Bay area. The colony established political freedom and a representative government. 5. Cambridge Agreement 1629 - The Puritan stockholders of the Massachusetts Bay Company agreed to emigrate to New England on the condition that they would have control of the government of the colony. 6. Puritan migration Many Puritans emigrated from England to America in the 1630s and 1640s. During this time, the population of the Massachusetts Bay colony grew to ten times its earlier population. 7. Church of England (Anglican Church) The national church of England, founded by King Henry VIII. It included both Roman Catholic and Protestant ideas. 8. John Winthrop (1588-1649), his beliefs 1629 - He became the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay colony, and served in that capacity from 1630 through 1649. -

Calvin Theological Seminary Covenant In

CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY COVENANT IN CONFLICT: THE CONTROVERSY OVER THE CHURCH COVENANT BETWEEN SAMUEL RUTHERFORD AND THOMAS HOOKER A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY SANG HYUCK AHN GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN MAY 2011 CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 3233 Burton SE • Grand Rapids, Michigan. 49546-4301 800388-6034 Jax: 616957-8621 [email protected] www.calvinserninary.edu This dissertation entitled COVENANT IN CONFLICT: THE CONTROVERSY OVER THE CHURCH COVENANT BETWEEN SAMUEL RUTHERFORD AND THOMAS HOOKER written by SANG HYUCK AHN and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has been accepted by the faculty of Calvin Theological Seminary upon the recommendation ofthe undersigned readers: Carl R Trueman, Ph.D. David M. Rylaarsda h.D. Date Acting Vice President for Academic Affairs Copyright © 2011 by Sang Hyuck Ahn All rights reserved To my Lord, the Head of the Church Soli Deo Gloria! CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ix ABSTRACT xi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 I. Statement of the Thesis 1 II. Statement of the Problem 2 III. Survey of Scholarship 6 IV. Sources and Outline 10 CHAPTER 2. THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF THE RUTHERFORD-HOOKER DISPUTE ABOUT CHURCH COVENANT 15 I. The Church Covenant in New England 15 1. Definitions 15 1) Church Covenant as a Document 15 2) Church Covenant as a Ceremony 20 3) Church Covenant as a Doctrine 22 2. Secondary Scholarship on the Church Covenant 24 II. Thomas Hooker and New England Congregationalism 31 1. A Short Biography 31 2. Thomas Hooker’s Life and His Congregationalism 33 1) The England Period, 1586-1630 33 2) The Holland Period, 1630-1633: Paget, Forbes, and Ames 34 3) The New England Period, 1633-1647 37 III. -

Thomas Hooker

TERCENTENARY COMMISSION OF THE STATE OF CONNECTICUT COMMITTEE ON HISTORICAL PUBLICATIONS IV Thomas Hooker PUBLISHED FOR THE TERCENTENARY COMMISSION 1933 "Reprinted November, 1957" TERCENTENARY COMMISSION OF THE STATE OF CONNECTICUT COMMITTEE ON HISTORICAL PUBLICATIONS Thomas Hooker WARREN SEYMOUR ARCHIBALD HESE years are years of remembrance in New England. We are reminded by these anniversaries of those who, crossing the At- lantic in such little ships as the Arbella and Tthe Griffin, laid down the keels of these ships of state, these free and noble commonwealths in which we have found safety in storms and pure delight in peace. One of the most notable of those journeymen of God was our own great fellow citizen, Thomas Hooker, a statesman of the first rank and a powerful preacher of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Thomas Hooker was born in 1586, in the hamlet of Marfield, in the parish of Tilton, in the county of Leices- ter, England. That region is the midland of England, and there in those neighborhoods of Stratford, Bedford, and Huntingdon were born Shakespeare, Bunyan, and Crom- well. From the hilltops in that parish you could see in his day, and you can see today, one of the most beautiful landscapes in that English countryside. On one of those hilltops stands St. Peter's Parish Church; a stone, Gothic church built in the middle of the twelfth century. It was 1 four hundred years old when Thomas Hooker was bap- tized at its old font in 1586, and it is almost eight hun- dred years old today. The parish had few inhabitants in the middle of the sixteenth century, and it had few in- habitants in the middle of the nineteenth. -

H Bavinck Preface Synopsis

University of Groningen Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae van den Belt, Hendrik; de Vries-van Uden, Mathilde Published in: The Bavinck review IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Belt, H., & de Vries-van Uden, M., (TRANS.) (2017). Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae. The Bavinck review, 8, 101-114. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 24-09-2021 BAVINCK REVIEW 8 (2017): 101–114 Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae Henk van den Belt and Mathilde de Vries-van Uden* Introduction to Bavinck’s Preface On the 10th of June 1880, one day after his promotion on the ethics of Zwingli, Herman Bavinck wrote the following in his journal: “And so everything passes by and the whole period as a student lies behind me. -

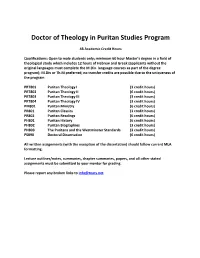

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program 48 Academic Credit Hours Qualifications: Open to male students only; minimum 60 hour Master’s degree in a field of theological study which includes 12 hours of Hebrew and Greek (applicants without the original languages must complete the M.Div. language courses as part of the degree program); M.Div or Th.M preferred; no transfer credits are possible due to the uniqueness of the program. PRT801 Puritan Theology I (3 credit hours) PRT802 Puritan Theology II (6 credit hours) PRT803 Puritan Theology III (3 credit hours) PRT804 Puritan Theology IV (3 credit hours) PM801 Puritan Ministry (6 credit hours) PR801 Puritan Classics (3 credit hours) PR802 Puritan Readings (6 credit hours) PH801 Puritan History (6 credit hours) PH802 Puritan Biographies (3 credit hours) PH803 The Puritans and the Westminster Standards (3 credit hours) PS890 Doctoral Dissertation (6 credit hours) All written assignments (with the exception of the dissertation) should follow current MLA formatting. Lecture outlines/notes, summaries, chapter summaries, papers, and all other stated assignments must be submitted to your mentor for grading. Please report any broken links to [email protected]. PRT801 PURITAN THEOLOGY I: (3 credit hours) Listen, outline, and take notes on the following lectures: Who were the Puritans? – Dr. Don Kistler [37min] Introduction to the Puritans – Stuart Olyott [59min] Introduction and Overview of the Puritans – Dr. Matthew McMahon [60min] English Puritan Theology: Puritan Identity – Dr. J.I. Packer [79] Lessons from the Puritans – Ian Murray [61min] What I have Learned from the Puritans – Mark Dever [75min] John Owen on God – Dr. -

John Cotton's Middle Way

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 John Cotton's Middle Way Gary Albert Rowland Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rowland, Gary Albert, "John Cotton's Middle Way" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 251. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/251 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN COTTON'S MIDDLE WAY A THESIS presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History The University of Mississippi by GARY A. ROWLAND August 2011 Copyright Gary A. Rowland 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Historians are divided concerning the ecclesiological thought of seventeenth-century minister John Cotton. Some argue that he supported a church structure based on suppression of lay rights in favor of the clergy, strengthening of synods above the authority of congregations, and increasingly narrow church membership requirements. By contrast, others arrive at virtually opposite conclusions. This thesis evaluates Cotton's correspondence and pamphlets through the lense of moderation to trace the evolution of Cotton's thought on these ecclesiological issues during his ministry in England and Massachusetts. Moderation is discussed in terms of compromise and the abatement of severity in the context of ecclesiastical toleration, the balance between lay and clerical power, and the extent of congregational and synodal authority. -

Curriculum Vitae—Greg Salazar

GREG A. SALAZAR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORICAL THEOLOGY PURITAN REFORMED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY PHD CANDIDATE, THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE 2965 Leonard Street Phone: (616) 432-3419 Grand Rapids, MI 49525 Email: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL OBJECTIVE To train and form the next generation of Reformed Christian leaders through a career of teaching and publishing in the areas of church history, historical theology, and systematic theology. I also plan to serve the Presbyterian church as a teaching elder through a ministry of shepherding, teaching, and preaching. EDUCATION The University of Cambridge (Selwyn College) 2013-2017 (projected) PhD in History Dissertation: “Daniel Featley and Calvinist Conformity in Early Stuart England” Supervisor: Professor Alex Walsham Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando 2009-2012 Master of Divinity The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2003-2007 Bachelor of Arts (Religious Studies) DOCTORAL RESEARCH My doctoral research is on the historical, theological, and intellectual contexts of the Reformation in England—specifically analyzing the doctrinal, ecclesiological, and pietistic links between puritanism and the post-Reformation English Church in the lead-up to the Westminster Assembly, through the lens of the English clergyman and Westminster divine Daniel Featley (1582-1645). AREAS OF RESEARCH SPECIALIZATION Broadly speaking, my competency and interests are in church history, historical theology, systematic theology, spiritual formation, and Islam. Specific Research Interests include: Post-Reformation -

William Perkins (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 Pm 1602) Earned a Bachelor’S Plenary Session # 1 Degree in 1581 and a Mas- Dr

MaY 19 (FrIDaY eVeNING) William perkinS (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 pm 1602) earned a bachelor’s plenary Session # 1 degree in 1581 and a mas- Dr. Sinclair Ferguson, ter’s degree in 1584 from WILLIAM William Perkins—A Plain Preacher Christ’s College in Cam- bridge. During those stu- dent years he joined up PERKINS MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY MOrNING) with Laurence Chaderton, CONFereNCe 9:00 - 10:15 am who became his personal plenary Session # 2 tutor and lifelong friend. IN THE ROUND CHURCH Dr. Joel Beeke Perkins and Chaderton met William Perkins’s Largest Case of Conscience with Richard Greenham, Richard Rogers, and others in a spiritual brotherhood 10:30 – 11:45 am at Cambridge that espoused Puritan convictions. plenary Session # 3 Dr. Geoff Thomas From 1584 until his death, Perkins served as lectur- The Pursuit of Godliness in the er, or preacher, at Great St. Andrew’s Church, Cam- Ministry of William Perkins bridge, a most influential pulpit across the street from Christ’s College. He also served as a teaching fellow 12:00 – 6:45 pm at Christ’s College, catechized students at Corpus Free Time Christi College on Thursday afternoons, and worked as a spiritual counselor on Sunday afternoons. In MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY eVeNING) these roles Perkins influenced a generation of young 7:00 – 8:15 pm students, including Richard Sibbes, John Cotton, John plenary Session # 4 Preston, and William Ames. Thomas Goodwin wrote Dr. Stephen Yuille that when he entered Cambridge, six of his instruc- Contending for the Faith: Faith and Love in Perkins’s tors who had sat under Perkins were still passing on Defense of the Protestant Religion his teaching. -

Natural Law and Covenant Theology in New England, 1620-1670 John D

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Natural Law Forum 1-1-1960 Natural Law and Covenant Theology in New England, 1620-1670 John D. Eusden Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/nd_naturallaw_forum Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Eusden, John D., "Natural Law and Covenant Theology in New England, 1620-1670" (1960). Natural Law Forum. Paper 47. http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/nd_naturallaw_forum/47 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Law Forum by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATURAL LAW AND COVENANT THEOLOGY IN NEW ENGLAND, 1620-1670* John D. Eusden ADDICTION TO STEREOTYPES has often prevailed over insight and research in studies of Puritan political life. Many investigators have described the early New England communities as "Bible commonwealths," theocracies, or would- be kingdoms of righteousness. These terms are partly true, but they tend to obscure the profundity of Puritan political philosophy by accentuation of biblicism, rigid morality, and the role of the clergy. The purpose of this essay is, first, to show that early New England leaders were as receptive to arguments drawn from nature and reason as they were to those from the Pentateuch and a moral code. The thesis offered is that the Puritans used natural law categories, understood in their own way, and that, although they were essentially products of the seventeenth century, they partly anticipated the political thought of the eighteenth. Secondly, it is hoped that this study of natural law among a Protestant group will help to probe the relationship between the faith which is rooted in Rome and that which stems from the Reformation. -

The Descendants of Rev. Thomas Hooker, 1909

ThedescendantsofRev.ThomasHooker,Hartford,Connecticut,1586-1908 The D escendants of Rev. T homas Hooker Hartford, C onnecticut 1586-1908 By E dward Hooker Commander, U .S. N. BEINGN A ACCOUNT OF WHAT IS KNOWN OF REV. THOMAS HOOKER* S FAMILY IN ENGLAND. AND MORE PARTICULARLY CONCERNING HIMSELF AND HIS INFLU ENCE UPON THE EARLY HISTORY OF OUR COUNTRY ALSO ALL ITEMS OF INTEREST WHICH IT HAS BEEN POSSIBLE TO GATHER CONCERNING THE EARLY GENERATIONS OF HOOKERS AND THEIR DESCENDANTS IN AMERICA Editedy b Margaret Huntington Hooker and printed for her at Rochester, N. Y. 1909 Copyrighted MARGARET H UNTINGTON HOOKER 1909 E.. R ANDREWS PRINTING COMPANY. ROCHESTER. N. Y '-» EDITORS N OTE i ^ T he many warm friends in all parts of the Country to *i w hom Commander Edward Hooker had endeared himself will O b e happy in having this result of his twenty-five years of earnest, p ainstaking labor at last available, and while he is not here to receive the thanks of his grateful kinsmen, nevertheless all descendants of Rev. Thomas Hooker surely unite in grati tude to him who gave time, money, and health so liberally in this permanent service to his family. In p reparing for the printer the work which blindness obliged him to leave incomplete, I have endeavored to follow his example of accuracy and honesty; in spite of this many errors and omissions may have unavoidably occurred and I shall be grateful to anyone who will call my attention to them, that they may be rectified in another edition. The u sual plan is followed in this Genealogy, of having the descendants numbered consecutively, the star (*) prefixed to the number indicating that the record of this person is carried forward another generation and will be found in the next gen eration under the same number, but in larger type and this time as head of a family. -

Chapter 5 Test Notes

SS-Chapter 5 Test Notes Test TOMORROW! These are mixed up from the actual test. If you would like to earn 5 bonus points, copy these in your handwriting and bring to class tomorrow. 1. The word expel means to force someone to leave a place. 2. The main reason the Puritans started the Massachusetts Bay Colony was to live according to their religious beliefs. 3. The major issue that caused King Philip’s War was that the colonists and Native Americans disagreed about ownership of the land. 4. John Winthrop led the Puritans from England to Massachusetts Bay Colony. 5. People first settled in the Connecticut River valley to have fertile land to farm. 6. One opinion of the Puritans was Roger Williams spread dangerous beliefs. 7. Town meetings were used to take care of town government. 8. Shipbuilding was an important industry in the New England Colonies. 9. The triangular trade routes connected England, the English colonies, and Africa. 10. The New England Colonies had representative government because they elected their own leaders. 11. Anne Hutchinson led followers to an island near Providence after being expelled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. 12. Thomas Hooker founded the settlement of Hartford, which became part of the Connecticut Colony. 13. John Winthrop led the second group of Puritans to New England in search of religious freedom and was an early leader of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. 14. Metacomet was the leader of the Wampanoag and tried to unite Native Americans against the colonists. 15. Roger Williams leader who was expelled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who later founded Providence, which became part of Rhode Island.