John Logan Koepke and David G. Robinson* in the Last Five Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V'j/SO14 RCA's Broadcast Antenna Center

V'J/SO14 Broadcast and Teleproduction Happenings PTL-'The Inspirational Network" Expands WDZL -TV, New 24 -Hour UHF RCA's Broadcast Antenna Center Quality Video's Mobile Unit www.americanradiohistory.com On the move. for you! 4,-. ..._V,. at" \ ,,\ 1 bt, . V I . O.. I . ` . .,S{+?f " \ Y '1 y^$(.. 4 , ,. P .. 1N " 1 , ; rÿ: I:IYf . ;-- ' !Í "' II-, i..R . a. : RCA Y{RWJä1sCAb7 6Y&Taa -1 f, ...,p,a- -.Ni l¡ JI ^ Idi.1 0 1 f' .i.w , +u. --^jyL ' r +,., p _ f ÿ'S 1, y, wpkM3.xyn. ,, nasr : . l . r -.-- / ( ,r w. }'Y, ) `r---._ .:. , a./ _ .*.Yd.g j 'i2N'-rE .., 3 s!Y ` 5 -,:. .` 'ß` ,...7.!: r.i/ .. 1 c.i` 1,'fy.VrY, *--rit, j+i .. ;j -'' - , }. - r* 1,:& r.1. `da .a ..\.". 47-77::` N1u " ` yy',, C ` .a..s"ç. _- 1, - l'3aa-y..í.-,.+D:.. `... View from United Slates Avenue There is a new RCA Broadcast Systems Di- We're moving toward a full integrated vision, operating from a new headquar- operation -consolidating administration, ters location in Gibbsboro, New Jersey. engineering and manufacturing in one Administrative operations- marketing, area for added efficiency and customer - product management, Tech Alert, cus- responsive service. tomer service and finance -are already in RCA Broadcast Systems move to Gibbs - place on site, and a new building is under boro reaffirms our commitment to remain construction. When completed later this the industry's leading supplier of quality year, TV transmitter engineering and pro- products, with unequalled support duction will move from Meadow Lands, services. -

42" 1080P LCD Flat Panel HDTV

L42FHD37 42" 1080p LCD Flat Panel HDTV Features and Benefits For the ultimate in High Definition viewing, RCA introduces the new Full 1080p L42FHD37. It featuresFull 1080p HDTV technology performance for crisp, lifelike details, SRS® WOW Audio Enhancement, fast panel response times, and 5 HD inputs: 3 HDMI (v1.3) and 2 HD Component. This television is also HDMI-CEC compliant making it easier to control your components connected via HDMI with the TV’s remote control. The RCA L42FHD37 is an incredible value that is designed to be a breeze to operate with stunning picture performance and sensible innovations. RCA HDTV. Color Beyond Reality. This TV is ENERGY STAR® qualified and features RCA’sIntuilight™ light sensor which detects ambient room light to automatically adjust contrast on the screen. The result is more energy-efficiency that is perfectly balanced for your room’s environment—night or day. PRODUCT SIZE (W X H X D) WITH stand: 40 X 28.4 X 10.2 INCHES || W/O stand: 40 X 26 X 4.4 INCHES * Cable TV subscription required. Check with your cable company for availability in your area. L42FHD37 Specifications JACK paNELS Side Panel Back Panel TECHNOLOGY REAR CONNECTIONS — OUTPUTS Tuner NTSC/ATSC/QAM Digital Audio Output (SPDIF) 1 - Optical Analog Video Formats (NTSC/480i) Composite, S-Vid, Component SIDE PANEL — INPUTS Video Formats (480p, 720p, 1080i, Component, RGB, HDMI Composite Video Input 1 1080p) S-Video Input 1 R L HDTV Capability Yes Audio Input for Composite 1 R L Category LCD HDMI Inputs ** 1 DVI AUDIO INPUT USB Input 1 - SW -

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

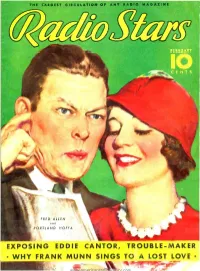

Exposing Eddie Cantor, Trouble -Maker Why Frank Munn Sings to a Lost Love

THE LARGEST CIRCULATION OF ANY RADIO MAGAZINE FRED ALLEN AND PORTLAND HOFFA EXPOSING EDDIE CANTOR, TROUBLE -MAKER WHY FRANK MUNN SINGS TO A LOST LOVE . www.americanradiohistory.com New Kind of Dry Rouge aCt y Ataiz.0 on ag cz'ary. ALL NIGMT f , ,d,u.,.,g,r.,,,, ,1,1 de, ,,,h, , . ra :°;'.r,;, NAIL 1,1_ How often you have noticed that most dry rouge seems to lose the i uiry of its color within an hour or so of its application. That is beeatse the sr.droucc particles are so coarse ve n texture, , that they simply, fall areuy from your skin. SAVAGE Rouge, as Your ,nse of touch will instantly tell you, is a great ,lead finer in restore and :miter thin ordinary rouge. Its particles being so infinitely line. adhere much more closely to the skin than rouge has ever clung before. In leer, SAVAGE Rouge, for this reason, clings so insistently, it seems to bee a part of the skin itself ... refusing to y eld, even to the savage caresses its tempting smoorhirers and poise- quickening color might easily invite. The price its ?Cc and the shades, to keep sour lips and cheeks in thrilling harmony, match perfects' drove of SAVAGE LIPSTICK . known as the o transparent-colored indelible lipstick that aer1.1,11y keeps lips seductively soft instead Of drain.e them as indelible lipstick usually does. Apply it rub it in, and delight i ,hiding your lips lusciously, lastingly tinted, yet utterly grease- less. Only :Cc .rid each or the tout hues is as vibrantly alluring, as completely intoxicating as a ¡oriole niche Everyone has found them so. -

The Pin-Up Boy of the Symphony: St. Louis and the Rise of Leonard

The Pin-Up Boy of the Symphony St. Louis and the Rise of Leonard Bernstein BY KENNETH H. WINN 34 | The Confluence | Fall/Winter 2018/2019 In May 1944 25-year-old publicized story from a New Leonard Bernstein, riding a York high school newspaper, had tidal wave of national publicity, bobbysoxers sighing over him as was invited to serve as a guest the “pin-up boy of the symphony.” conductor of the St. Louis They, however, advised him to get The Pin-Up Boy 3 Symphony Orchestra for its a crew cut. 1944–1945 season. The orchestra For some of Bernstein’s of the Symphony and Bernstein later revealed that elders, it was too much, too they had also struck a deal with fast. Many music critics were St. Louis and the RCA’s Victor Records to make his skeptical, put off by the torrent first classical record, a symphony of praise. “Glamourpuss,” they Rise of Leonard Bernstein of his own composition, entitled called him, the “Wunderkind Jeremiah. Little more than a year of the Western World.”4 They BY KENNETH H. WINN earlier, the New York Philharmonic suspected Bernstein’s performance music director Artur Rodziński Jeremiah was the first of Leonard Bernstein’s was simply a flash-in-the-pan. had hired Bernstein on his 24th symphonies recorded by the St. Louis Symphony The young conductor was riding birthday as an assistant conductor, Orchestra in the spring of 1944. (Image: Washing- a wave of luck rather than a wave a position of honor, but one known ton University Libraries, Gaylord Music Library) of talent. -

LP Inventory

Allen Red Ride, Red, Ride RCA $ 5 Allen Red With Coleman Hawkins Smithsonian $ 5 Allen Red Live at the Roundtable Forum Records $ 5 Allen Steve With Gus Bivona - Music For Swingers Mercury $ 5 Allison Mose Ever Since The World Ended Blue Note $ 5 Alpert Herb Going Places A&M Records $ 5 Alpert Herb South of the Border A&M Records $ 5 Armstrong Louis Ambassador Satch Columbia Hi Fidelity $ 5 Armstrong Louis With the Dukes of Dixieland Audio Fidelity $ 5 Armstrong Louis Greatest Of Columbia Records $ 5 Armstrong Louis Hot Fives and Hot Sevens Columbia Masterpieces $ 5 Armstrong Louis Live Recording Polskie Records $ 5 Armstrong Louis Plays W.C. Handy Columbia $ 5 Armstrong Louis The Greatest of L. Armstrong Columbia $ 5 Armstrong Louis The Hot 5’s and Hot 7’s Columbia Masterpieces $ 5 Armstrong Louis Giants of Jazz Series Time-Life $ 10 Armstrong Louis Town Hall Concert RCA $ 5 Artin Tom Condon’s Hot Lunch Slide Records $ 5 Astaire Fred Starring Fred Astaire Columbia $ 5 Auld George Manhattan Coral Records $ 5 Ballou Monte Moving Willie’s Grave $ 5 Barefield Eddie Indestructible Eddie Barefield Famous Records $ 5 Barnet Charlie Best Of MCA $ 5 Basie Count Basie's Basement feat. Jimmy Rushing $ 5 Basie Count Basie's Best Columbia $ 5 Basie Count Best Of Decca $ 5 Basie Count Blues By Basie Columbia (set of four ’78 discs $ 10 Basie Count Good Morning Blues $ 5 Basie Count In Kansas City 1930-32 RCA $ 5 Basie Count The Count RCA Camden $ 5 Basie Count The Count’s Men $ 5 Basie Count & Duke Ellington Great Jazz 1940 Jazz Anthology $ 5 Basie -

RCA Victor LPV 500 Series

RCA Discography Part 23 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor LPV 500 Series This series contains reissues of material originally released on Bluebird 78 RPM’s LPV 501 – Body and Soul – Coleman Hawkins [1964] St. Louis Shuffle/Wherever There's A Will, Baby/If I Could Be With You/Sugar Foot Stomp/Hocus Pocus/Early Session Hop/Dinah/Sheikh Of Araby/Say It Isn't So/Half Step Down, Please/I Love You/Vie En Rose/Algiers Bounce/April In Paris/Just Friends LPV 502 – Dust Bowl Ballads – Woody Guthrie [1964] Great Dust Storm/I Ain't Got No Home In This World Anymore/Talkin' Dust Bowl Blues/Vigilante Man/Dust Cain't Kill Me/Pretty Boy Floyd/Dust Pneumonia Blues/Blowin' Down This Road/Tom Joad/Dust Bowl Refugee/Do Re Mi/Dust Bowl Blues/Dusty Old Dust LPV 503 – Lady in the Dark/Down in the Valley: An American Folk Opera – RCA Victor Orchestra [1964] Lady In The Dark: Glamour Music Medley: Oh Fabulous One, Huxley, Girl Of The Moment/One Life To Live/This Is New/The Princess Of Pure Delight/The Saga Of Jenny/My Ship/Down In The Valley LPV 504 – Great Isham Jones and His Orchestra – Isham Jones [1964] Blue Prelude/Sentimental Gentleman From Georgia/(When It's) Darkness On The Delta/I'll Never Have To Dream Again/China Boy/All Mine - Almost/It's Funny To Everyone But Me/Dallas Blues/For All We Know/The Blue Room/Ridin' Around In The Rain/Georgia Jubilee/You've Got Me Crying Again/Louisville Lady/A Little Street Where Old Friends Meet/Why Can't This Night Go On Forever LPV 505 – Midnight Special – Leadbelly [1964] Easy Rider/Good Morning Blues/Pick A Bale Of Cotton/Sail On, Little Girl, Sail On/New York City/Rock Island Line/Roberta/Gray Goose/The Midnight Special/Alberta/You Can't Lose-A Me Cholly/T.B. -

Appendix C2 Joint Project Review

Lake Street Storage Project Appendix C2 Joint Project Review (JPR 18-08-29-01) for the LEAP 2018-02/Lake Street Project, Regional Conservation Agency (RCA), April 8, 2019 Board of Directors Chairperson Jonathan Ingram City of Murrieta April 8, 2019 Daniela Andrade City of Banning Julio Martinez Karin Cleary-Rose City of Beaumont U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ed Clark City of Calimesa 777 East Tahquitz Canyon Way, Suite 208 Larry Greene Palm Springs, California 92262 City of Canyon Lake Jacque Casillas Joanna Gibson City of Corona California Dept. of Fish and Wildlife Jocelyn Yow 3602 Inland Empire Blvd. #C220 City of Eastvale Ontario, California 91764 Michael Perciful City of Hemet Lorena Barajas City of Jurupa Valley Shipping Cover: Natasha Johnson Vice Chairperson City of Lake Elsinore Karin and Joanna, Lesa Sobek City of Menifee David Marquez Please find the following JPR attached: City of Moreno Valley Kevin Bash JPR 18-08-29-01. The Permittee is City of Lake Elsinore. The local identifier is LEAP City of Norco 2018-02/ Lake Street Storage Project. The JPR file attached includes the following: David Starr Rabb City of Perris RCA JPR Findings Andy Melendrez City of Riverside Exhibit A, Vicinity Map with MSHCP Schematic Cores and Linkages Crystal Ruiz Exhibit B, Criteria Area Cells with Riverside Country Vegetation and City of San Jacinto Project Location James Stewart Exhibit C, Criteria Area Cells with MSHCP Soils and Project Location City of Temecula . Exhibit D, Conservation and Avoidance Areas Joseph Morabito City of Wildomar . Regional Map MSHCP Consistency Findings, by City of Lake Elsinore Dream Extreme, Kevin Jeffries County of Riverside February 15, 2019 Karen Spiegel Habitat Assessment and Western Riverside County Multiple Species County of Riverside Habitat Conservation Plan Consistency Analysis for the Lake Street Chuck Washington Storage Project, by Soar Environmental Consulting, March 25, 2019 County of Riverside Lake Street Storage Fencing Plan MSHCP Consistency Letter, by Soar V. -

The Essential Reference Guide for Filmmakers

THE ESSENTIAL REFERENCE GUIDE FOR FILMMAKERS IDEAS AND TECHNOLOGY IDEAS AND TECHNOLOGY AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ESSENTIAL REFERENCE GUIDE FOR FILMMAKERS Good films—those that e1ectively communicate the desired message—are the result of an almost magical blend of ideas and technological ingredients. And with an understanding of the tools and techniques available to the filmmaker, you can truly realize your vision. The “idea” ingredient is well documented, for beginner and professional alike. Books covering virtually all aspects of the aesthetics and mechanics of filmmaking abound—how to choose an appropriate film style, the importance of sound, how to write an e1ective film script, the basic elements of visual continuity, etc. Although equally important, becoming fluent with the technological aspects of filmmaking can be intimidating. With that in mind, we have produced this book, The Essential Reference Guide for Filmmakers. In it you will find technical information—about light meters, cameras, light, film selection, postproduction, and workflows—in an easy-to-read- and-apply format. Ours is a business that’s more than 100 years old, and from the beginning, Kodak has recognized that cinema is a form of artistic expression. Today’s cinematographers have at their disposal a variety of tools to assist them in manipulating and fine-tuning their images. And with all the changes taking place in film, digital, and hybrid technologies, you are involved with the entertainment industry at one of its most dynamic times. As you enter the exciting world of cinematography, remember that Kodak is an absolute treasure trove of information, and we are here to assist you in your journey. -

History of Sound Motion Pictures by Edward W Kellogg Second

History of Sound Motion Pictures by Edward W Kellogg Second Installment History of Sound Motion Pictures by Edward W Kellogg Our thanks to Tom Fine for finding and scanning the Kellogg paper, which we present here as a “searchable image”. John G. (Jay) McKnight, Chair AES Historical Committee 2003 Dec 04 Copyright © 1955 SMPTE. Reprinted from the Journal of the SMPTE, 1955 June, pp 291...302; July, pp 356...374; and August, pp 422...437. This material is posted here with permission of the SMPTE. Internal or personal use of this material is permitted. However, permission to reprint/republish this material for advertising or promotional purposes or for creating new collective works for resale or redistribution must be obtained from the SMPTE. By choosing to view this document, you agree to all provisions of the copyright laws protecting it. SECOND INSTALLMENT History of Sound Motion Pictures By EDWARD W. KELLOGG For the abstract of this paper which was presented on May 5,1954, at the Society’s Convention at Washington, D.C., see the first installment published in last month’s As one who shared in this misjudg- Journal. ment, I would like to suggest to readers that it is difficult today to divest oneself of the benefit of hindsight. At that time, The Motion Picture Industry “The art of the silent film had at- the principal examples of sound pictures Adopts Sound tained superb quality and the public we had seen were demonstration films, Many Commercially Unsuccessful Eforts. was satisfied. Why then, producers very interesting to us sound engineers The historical outline with which our asked, should Hollywood scrap the working on the project, but scarcely story began contains a very incomplete bulk of its assets, undertake staggering having entertainment value. -

ELECTRONICS PIONEER Lee De Forest

ELECTRONICS PIONEER Lee De Forest by I. E. Levine author of MIRACLE MAN OF PRINTING: Ottmar M1ergenthaler, etc. In 1913 the U. S. Government indicted a scientist on charges that could have sent him to prison for a decade. An angry prosecutor branded the defendant a charlatan, and accused him of defrauding the public by selling stock to manufacture a worthless device. Fortunately for the future of electronics - and for the dignity of justice - the defendant was found innocent. He was the brilliant inventor. Lee De Forest, and the so-called worthless device was a triode vacuum tube called an Audion; the most valuable discovery in the history of electronics. From his father, a minister and college president, young De Forest acquired a strength of character and purpose that helped him work his way through Yale and left him undismayed by early failures. Ilis first successful invention was a wireless receiver far superior to Marconi's. Soon he devised a revolutionary trans- mitter, and at thirty was manufacturing his own equip- ment. Then his success was wiped out by an unscrup- ulous financier. De Forest started all over again, per- fected his priceless Audion tube and paved the way for radio broadcasting in America. Time and again it was only De Forest's faith that helped him surmount the obstacles and indignities thrust upon him by others. Greedy men and powerful corporations took his money, infringed on his patents and secured rights to his inventions for only a fraction of their true worth. Yet nothing crushed his spirit or blurred his scientific vision. -

![[History Of] Motion Picture Sound Recording](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0301/history-of-motion-picture-sound-recording-4300301.webp)

[History Of] Motion Picture Sound Recording

straight-line portion of the negative H & D curve, the print The negative track is recorded on a high gamma positive being made on the straight-line portion of the print H & D type film in contrast to a low negative gamma film for the curve. Light valve recording followed the basic principles variable-density method. Since the major studios had al- of rendering tone values laid down by L. A. Jones of ready installed the ERPI variable-density system, RCA Eastman Kodak Co. [5]. An excellent analysis of straight bought up RKO Pictures and installed its variable-area line and toe records was made by Mackenzie [6] in 1931 system, a refinement of General Electric's earlier efforts and shown in Fig. 4. [7]. Walt Disney Studioslater adopted the RCA system. While the variable-density systems were being intro- After that, variable density dominated the industry until the duced into the motion picture industry, another type of mid-Forties, when the variable-ama method became more track, now known as variable area, was being developed. In popular. Almost every motion picture studio now uses variable area recording. I \ ' _ I ',, I i , I PRINTER H &D CURVES _ I OVERALL HLD CURVES /3 _Z_,_o - '--i _i_<_ _%%,,o Noise Reduction _" --_ ;2 _]"'"'.,._'4 I , The first technical improvement in sound recording was \ \ _--- i I--_' - This was done on variable-density tracks by superimposing [X.,*x_--_---_--_- a biasing current on the ribbons, reducing the spacing from ] _ ..... i i__--__:/:!L-2_- the ihtroduction of ground noise reduction techniques [8].