Thailand - Market Entry Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Policy and Bilingual Education in Thailand: Reconciling the Past, Anticipating the Future1

LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network Journal, Volume 12, Issue 1, January 2019 Language Policy and Bilingual Education in Thailand: Reconciling the Past, Anticipating the Future1 Thom Huebner San José State University, USA [email protected] Abstract Despite a century-old narrative as a monolingual country with quaint regional dialects, Thailand is in fact a country of vast linguistic diversity, where a population of approximately 60 million speak more than 70 languages representing five distinct language families (Luangthongkum, 2007; Premsrirat, 2011; Smalley, 1994), the result of a history of migration, cultural contact and annexation (Sridhar, 1996). However, more and more of the country’s linguistic resources are being recognized and employed to deal with both the centrifugal force of globalization and the centripetal force of economic and political unrest. Using Edwards’ (1992) sociopolitical typology of minority language situations and a comparative case study method, the current paper examines two minority language situations (Ferguson, 1991), one in the South and one in the Northeast, and describes how education reforms are attempting to address the economic and social challenges in each. Keywords: Language Policy, Bilingual Education, the Thai Context Background Since the early Twentieth Century, as a part of a larger effort at nation-building and creation of a sense of “Thai-ness.” (Howard, 2012; Laungaramsri, 2003; Simpson & Thammasathien, 2007), the Thai government has pursued a policy of monolingualism, establishing as the standard, official and national language a variety of Thai based on the dialect spoken in the central plains by ethnic Thais (Spolsky, 2004). In the official narrative presented to the outside world, Thais descended monoethnic and monocultural, from Southern China, bringing their language with them, which, in contact with indigenous languages, borrowed vocabulary. -

1 the Master Plan for Conservation

0 State of Conservation Report on the Historic City of Ayutthaya World Heritage Property Thailand Submitted to the World Heritage Centre by 1 December 2018 CONTENTS page Executive Summary 1 Details of Thailand’s Implementation of the World Heritage Committee Decision 2 41 COM 7B.98, 41st session of the Committee (Kraków, 2017) Annex 1: Executive Summary of draft updated Master Plan for Conservation and 18 Development of Historic City of Ayutthaya (2018-2027) Annex 2: Notification on Rules and Procedure in Pursuing Permission of Building 32 Construction within Ayutthaya City Island’s Archaeological Area (1997) Annex 3: Notification on Rules and Procedure in Pursuing Permission of Building 36 Construction within Ayutthaya City Island’s Archaeological Area (updated edition) compared with the 1997 Notification Summary The Fine Arts Department, Ministry of Culture of Thailand has actively undertaken conservation and management measures at the Historic City of Ayutthaya in line with the recommendations from the World Heritage Committee in Decision 41 COM 7B.98. Capacity building activities in monument conservation have been conducted with the development of a curriculum and on-site training based on scientific conservation principles and the use of traditional materials and skills. The comprehensive revision of the Master Plan for Conservation and Development (2018-2027) has been finalized. The updated Master Plan provides a comprehensive and over-arching framework to address the World Heritage Committee’s concerns regarding conservation and utilization, which includes sub-plans specifically related to a conservation and utilization within the Historic City of Ayutthaya such as, a systematic strategy for disaster risk reduction and the additional updated regulations to control development within the property. -

The Puzzling Absence of Ethnicity-Based Political Cleavages in Northeastern Thailand

Proud to be Thai: The Puzzling Absence of Ethnicity- Based Political Cleavages in Northeastern Thailand Jacob I. Ricks Abstract Underneath the veneer of a homogenous state-approved Thai ethnicity, Thailand is home to a heterogeneous population. Only about one-third of Thailand’s inhabitants speak the national language as their mother tongue; multiple alternate ethnolinguistic groups comprise the remainder of the population, with the Lao in the northeast, often called Isan people, being the largest at 28 percent of the population. Ethnic divisions closely align with areas of political party strength: the Thai Rak Thai Party and its subsequent incarnations have enjoyed strong support from Isan people and Khammuang speakers in the north while the Democrat Party dominates among the Thai- and Paktay-speaking people of the central plains and the south. Despite this confluence of ethnicity and political party support, we see very little mobilization along ethnic cleavages. Why? I argue that ethnic mobilization remains minimal because of the large-scale public acceptance and embrace of the government-approved Thai identity. Even among the country’s most disadvantaged, such as Isan people, support is still strong for “Thai-ness.” Most inhabitants of Thailand espouse the mantra that to Copyright (c) Pacific Affairs. All rights reserved. be Thai is superior to being labelled as part of an alternate ethnic group. I demonstrate this through the application of large-scale survey data as well as a set of interviews with self-identified Isan people. The findings suggest that the Thai state has successfully inculcated a sense of national identity Delivered by Ingenta to IP: 192.168.39.151 on: Sat, 25 Sep 2021 22:54:19 among the Isan people and that ethnic mobilization is hindered by ardent nationalism. -

CH List A4 2016 C-Band

ชองรายการสำหรับผูที่ใชจานตะแกรง C-Band มีผล 24 กุมภาพันธ 2559 เปนตนไป ชองชั้นนำ 52 True Film Asia* รายการบันเทิง 1 True Plook Panya 53 True Asian Series* 116 Workpoint HD HD 3 Channel 3 HD HD 54 True Spark* 118 MIRACLE TV 5 BBTV CH7 HD HD 55 True Explore Life* 120 Dara daily 6 Toon Channel 56 True Sport HD3* HD 121 MAYA CHANNEL 8 True Music 57 True Sport2* 122 Gen C 9 MCOT HD HD 58 True Sport7* 124 MGTV 10 True Select 59 True Thai Film** 126 Thai Chaiyo ชองดิจิตอลทีวี 60 True Movie Hits** 127 MITI 4 11 TV5 HD HD 61 True X-Zyte** 128 KURU 12 NBT 62 Reality Channel HD HD 129 Zabb TV 13 THAIPBS HD HD 63 True Sport 6* 130 Dara Channel 20 TP TV 64 True Sport HD2 (ชองเติมเงิน) HD 131 Hi 23 3 Family รายการเด็ก 132 Living show 24 MCOT Family 89 Boomerang 134 Aonzon HD TV 25 LOCA 90 TOONAMI 136 Jewelry Channel 26 TNN24 91 Cartoon Club 138 SEXY Channel 27 Thai TV 92 Gang Cartoon 139 13 Siam Thai 28 NEW TV 93 JA TING JA 140 BTU Channel 29 SPRINGNEWS True Zone 141 Kaset Rumruay 30 BRIGHT TV 94 Reality Channel 142 E-SAN TV 31 VOICE TV 95 Fox Thai 145 Giffarine 32 NATION TV ภาพยนตร และซีรี่ส 146 S Channel 33 Workpoint TV 97 Mongkol Channel 147 TCCTV 34 TRUE4U 98 M Channel 148 Kaset Happy 35 GMM 25 99 JKN 149 ปง แชนแนล 36 NOW 100 Next movie 150 UMMTV 37 CH8 101 TV ThaiBan 151 RSU Wiom TV 38 3 SD 102 Next-Wan Van 152 SHOP CHANNEL 39 Mono TV 103 Media Channel 154 Love TV 40 MCOT HD 104 MV Mix-Major 155 ThaiVisions Ch 41 One HD HD 105 MV Major Asian 156 SMART TV 42 Thairath TV HD HD 107 Movies Max 157 JJ Channel 43 Channel 3 HD 108 Best Channel 158 Maxagro -

Forging Ahead

BEC WORLD PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED FORGING AHEAD ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Contents 01 16 63 Important Financial Data Awards in Year 2020 Financial Statements 04 22 123 Board of Directors’ Report The BEC World Group Revenue Structure 06 23 125 Audit & Risk Committee Report Business Operation List of Top Ten Largest of BEC World Group Shareholders 08 Report of The Nomination 30 128 and Remuneration Committee Business Operation Management Structure Policy and Overview and Corporate Governance 09 Corporate Governance 43 189 Committee Report Risk Factors Internal Control and Risk Management 10 48 Board of Directors Management Discussion 192 and Analysis: MD&A Connected Transactions 12 Management Team 59 195 Report of The Board Subsidiaries and Associates of Directors’ Responsibilities Information 14 for The Financial Statements 51 Years BEC World Group’s Milestone 198 60 CV of Directors, Executive Auditor’s Report Officers, Chief Compliance Officer and Company Secretary 215 Reference Persons Investors can and more information regarding the Company from the Company’s Disclosure Report (Form 56-1) which has been displayed at www.sec.or.th or www.becworld.com Annual Report 2020 BEC World Public Company Limited Important Financial Data Unit : Million Baht 2020** 2019 2018 Total Asset 9,518 11,354 14,320 Total liabilities 4,109 5,636 8,084 Total Shareholders’ equity 5,409 5,718 6,236 Revenue from sale 5,860 8,310 10,125 Total revenues 5,945 8,751 10,236 Gross Margin 1,278 774 1,339 Net Profit (Loss) (214) (397) (330) Financial Ratio Nat Profit to Total Revenues -3.66% -4.78% -3.26% Return on Total Shareholders’ Equity -7.20% -6.78% -5.29% Return on Total Assets -2.05% -3.98% -2.68% Net Profit (loss) Per Shares (Baht) (0.11) (0.20) (0.17) Dividend Per Share (Baht) -* - - Book Value Per Share (Baht) 2.70 2.86 3.12 Note : * On March 19, 2020, the Board of Directors’ Meeting No. -

48 Hours in Bangkok: Eat, Play, Sleep What Is the Perfect Trip in Bangkok for 2 Days

48 Hours in Bangkok: Eat, Play, Sleep What is the perfect trip in Bangkok for 2 days DAY 1 Eat - Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner Breakfast Breakfast at the Royal Orchid Sheraton’s FEAST - There's something for everyone at this world Feast at Royal Orchid cuisine dining spot with an exceptional choice of breakfast options (including something Sheraton Hotel & Towers, Charoen Krung Road, for the kids). Bang Rak Get an early start on your 48 hours in Bangkok and head to Feast any time from 6:00 AM - 10:30 AM. Call +66 (0) 2266 0123 or email: [email protected] Lunch Lunch at Eat Sight Story - A real gem hidden down a tiny Bangkok alleyway, complete with river and temple views. Eat Sight Story, Tatien, Maharaj Road Eat Sight Story serve a delicious array of classic Thai and fusion cuisine...plus a cocktail menu worth exploring. Call +66 (0) 2622 2163 Dinner Early dinner or late lunch at Somtum Der - Absorb the art of authentic Som Tum (papaya salad) in this cosy and welcoming eatery. Somtum Der, Saladang, Somtum Der has a laid back outside eating area that creates a captivating eat-like-a-local vibe Silom as you tuck into some Tum Thai with fresh papaya, zesty lime and chili. Call +66 (0) 2632 4499 1 Play – Don’t Miss Out! Temple hopping Exploring the many incredibly beautiful temples in Bangkok has to be done, and the Grand Palace is top of the must-see attractions. The Grand Palace has been the ocial residence of the Kings of Siam and Thailand since the 1700’s and is also home to the temple of the Emerald Buddha. -

Coastal Shrimp Farming in Thailand: Searching for Sustainability

7 Coastal Shrimp Farming in Thailand: Searching for Sustainability B. Szuster Department of Geography, University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Shrimp farming in Thailand provides a fascinating example of how the global trade in agricultural com- modities can produce rapid transformations in land use and resource allocation within coastal regions of tropical developing nations. These transformations can have profound implications for the long-term integrity of coastal ecosystems, and represent a significant challenge to government agencies attempting to manage land and water resources. Thailand’s shrimp-farming industry has suffered numerous regional ‘boom and bust’ production cycles that created considerable environmental damage in rural communities. At a national scale, these events were largely masked, however, by a shifting cultivation strategy and local adaptations in husbandry techniques. This chapter outlines the need to upgrade plan- ning systems, improve water supply infrastructure and enhance extension training services within coastal communities to address ongoing systemic environmental management problems within the Thai shrimp-farming industry. Introduction Environmental problems have created widespread crop failures throughout In Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, Thailand, but a predicted national-level col- the Red Queen tells Alice that ‘in this place it lapse in farmed shrimp production has not takes all the running you can do to keep in occurred (Dierberg and Kiattisimkul, 1996; the same place’. This phrase has been used to Vandergeest et al., 1999). This chapter traces illustrate a variety of natural and social phe- the development of shrimp farming in nomena (Van Valen, 1973) and it also aptly Thailand. -

Thailand: History & Culture

http://asiasociety.org/policy-politics?newsid=77892 Thailand: History & Culture An AsiaTODAY special report (April 11, 2002): Celebrate Thai New Year news stories; multimedia; recipes; Thai temples; links & resources Ed's Photos: The A gallery of photos by Ed Kaspar Thailand Galleries The History of Thailand A brief illustrated history Created by Michael Leming: student-written The Karen of Northern ethnographic report (1999): Karen Weblinks; a Thailand Web museum of artifacts; video; bibliography A Smithsonian Magazine article on a bust of King Mongkut in the Smithsonian collection, debunking The Object at Hand the caricature of the king perpetuated by the musical The King & I Introduction to "the people, arts & cultures of South Thailand between the Thai & Malay Worlds The South Thailand on the Golden Peninsula": research projects & Homepage publications of Ryoko Nishii, Alexander Horstmann, & others; photo gallery; links A Frenchman's perspectives on Thai society & Thai WorldView culture Research on "the region of mainland Southeast Asia & those areas of the Peoples Republic of Thai-Yunnan Project China, particularly Yunnan,which have had long cultural, economic & social relations with each other" Thailand: SiamWEB Discussion forum for people with interest in Cyber Culture Thailand, general information & news, etc. History & culture, sights & experiences, travel Tourism Thailand tips & information Ups and Downs: Anchalee Chaiworaporn's program notes for the Thai Cinema in 2003 Udine Far East Film Festival 2004 The Making of a Nation Thailand is one of the few countries in the world which has never been colonised.The first independent Thai Kingdom was established in 1238, but the origins of Thailand and the Thai people go back much further. -

The Transport Trend of Thailand and Malaysia

Executive Summary Report The Potential Assessment and Readiness of Transport Infrastructure and Services in Thailand for ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) Content Page 1. Introduction 1.1 Rationales 1 1.2 Objectives of Study 1 1.3 Scopes of Study 2 1.4 Methodology of Study 4 2. Current Status of Thailand Transport System in Line with Transport Agreement of ASEAN Community 2.1 Master Plan and Agreement on Transport System in ASEAN 5 2.2 Major Transport Systems for ASEAN Economic Community 7 2.2.1 ASEAN Highway Network 7 2.2.2 Major Railway Network for ASEAN Economic Community 9 2.2.3 Main Land Border Passes for ASEAN Economic Community 10 2.2.4 Main Ports for ASEAN Economic Community 11 2.2.5 Main Airports for ASEAN Economic Community 12 2.3 Efficiency of Current Transport System for ASEAN Economic Community 12 3. Performance of Thailand Economy and Transport Trend after the Beginning of ASEAN Economic Community 3.1 Factors Affecting Cross-Border Trade and Transit 14 3.2 Economic Development for Production Base Thriving in Thailand 15 3.2.1 The analysis of International Economic and Trade of Thailand and ASEAN 15 3.2.2 Major Production Bases and Commodity Flow of Prospect Products 16 3.2.3 Selection of Potential Industries to be the Common Production Bases of Thailand 17 and ASEAN 3.2.4 Current Situation of Targeted Industries 18 3.2.5 Linkage of Targeted Industries at Border Areas, Important Production Bases, 19 and Inner Domestic Areas TransConsult Co., Ltd. King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi 2T Consulting and Management Co., Ltd. -

Not for Quote the OFFICIAL DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE AS

Preliminary Draft: not for Quote THE OFFICIAL DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE AS A CATALYST OF FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT AND INDUSTRIAL AGGLOMERATION Matsuo WATANABE Japan Institute of International Affairs 1. INTRODUCTION This chapter is intended to investigate the contribution of infrastructure development financed by official development assistance (ODA) to attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and formation of industrial agglomeration with reference to the automotive industry in Thailand. Thailand has been one of the major production bases in the ASEAN, and currently there are 700 automotive-related companies. The origin of the industry in Thailand dates back to the 1960s when the country invited foreign manufacturers, mainly Japanese, under the import substitution industrialisation (ISI) strategy. The country subsequently changed to an export-oriented strategy in the beginning of the 1970s afterwards which has led to the remarkable success of industrialisation (including automotive sector) and economic development. The success of Thai automotive industry is represented by the expansion of volume of production and export which has been the largest among ASEAN members. This expansion is enabled by a concentration of investments in the industry (known as ‘agglomeration’), among others, from foreign part suppliers in the Eastern Seaboard (ESB) area. The determinants of FDI have been analysed in number of past literature including FDI to the ASEAN economies in which provision of infrastructure as well as existence of industrial agglomeration have positive impacts on attracting FDI1. 1 For example, Kohama and Urata (2001) stress the importance of host countries’ condition in 1 This study investigates how the agglomeration of automotive industry has taken place in Thailand. -

Overview of Actions Taken by Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation (BTCF)

Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation COVID-19 Relief Action Report #4 Overview of Actions taken by Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation (BTCF) As of 12 May, BTCF has: ● Distributed relief aid in 53 countries/regions (blue) with more distributions on the way for another 28 countries/regions (orange) ● A total of 14,466,805 items have been distributed with a further 7,440,677 items scheduled to be distributed ● Mid-term COVID-19 relief action plans have been initiated by BTCF chapters around the world including financial aid, material supplies and caring social support Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation COVID-19 Relief Action Report #4 Highlights by Region: Asia The Asia region, consisting of around 60% of the world’s population, is the most populated and diverse region in the world. Being the epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic, most countries/regions in Asia experienced or are still experiencing severe lockdown restrictions. The cascading decline on local and national economy, along with lack of income and steep inflation of daily costs, have left our vulnerable communities struggling, wondering where their next meal may be. BTCF, founded in this region, has been supporting local Region Highlights communities for over half a century. Immediately, in early February, BTCF disaster management protocols were initiated and teams from different regions were dispatched to contact families Malaysia and individuals in our care. Understanding their needs, BTCF ● Care assistance for vulnerable communities. chapters quickly established suitable action plans and began the ● Long term partnerships paving the way for procurement of food supplies, necessities and personal protective COVID-19 co-operation. -

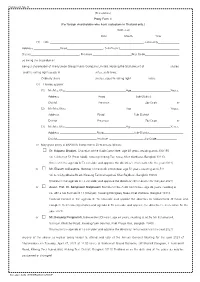

Proxy Form C (For Foreign Shareholders Who Have Custodians In

Enclosure No. 9 (Translation) Proxy Form C (For foreign shareholders who have custodians in Thailand only.) Written at Date Month Year (1) I/We , nationality Address Road , Sub-District District , Province Post Code as being the custodian of being a shareholder of The Erawan Group Public Company Limited, Holding the total amount of shares and the voting right equals to votes, as follows; Ordinary share shares, equal to voting right votes (2) Hereby appoint (1) Mr./Mrs./Miss Age Years, Address Road Sub-District District Province Zip Code or (2) Mr./Mrs./Miss Age Years, Address Road Sub-District District Province Zip Code or (3) Mr./Mrs./Miss Age Years, Address Road Sub-District District Province Zip Code or May grant proxy to ERAWAN Independent Directors as follows: Dr. Kulpatra Sirodom, Chairman of the Audit Committee, age 65 years, residing at no.100/155 Soi Sukhumvit 53 (Paidi Madi), Kwaeng Khlong Tan Nuea, Khet Watthana, Bangkok 10110. (Interest in the agenda 6: To consider and approve the directors' remuneration for the year 2021) or Mr. Ekasith Jotikasthira, Member of the Audit Committee, age 51 years, residing at no.511 Soi 6, Sri-Ayudhaya Road, Kwaeng Tanonphayathai, Khet Rajdhevi, Bangkok 10400. (Interest in the agenda 6: To consider and approve the directors' remuneration for the year 2021) or Assoc. Prof. Dr. Somprawin Manprasert, Member of the Audit Committee, age 46 years, residing at no. 48/12 Soi Sukhumvit 11 (Chaiyot), Kwaeng Klongtoey Nuea, Khet Wattana, Bangkok 10110. (Special interest in the agenda 5: To consider and appoint the directors in replacement of those who complete their terms by rotation and agenda 6: To consider and approve the directors' remuneration for the year 2021) or Mr.