H-Diplo | ISSF Article Review No. 2 on Gautam Mukunda, “We Cannot Go

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telling the Story of the Royal Navy and Its People in the 20Th & 21St

NATIONAL Telling the story of the Royal Navy and its people MUSEUM in the 20th & 21st Centuries OF THE ROYAL NAVY Storehouse 10: New Galleries Project: Exhibition Design Report JULY 2011 NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE ROYAL NAVY Telling the story of the Royal Navy and its people in the 20th & 21st Centuries Storehouse 10: New Galleries Project: Exhibition Design Report 2 EXHIBITION DESIGN REPORT Contents Contents 1.0 Executive Summary 2.0 Introduction 2.1 Vision, Goal and Mission 2.2 Strategic Context 2.3 Exhibition Objectives 3.0 Design Brief 3.1 Interpretation Strategy 3.2 Target Audiences 3.3 Learning & Participation 3.4 Exhibition Themes 3.5 Special Exhibition Gallery 3.6 Content Detail 4.0 Design Proposals 4.1 Gallery Plan 4.2 Gallery Plan: Visitor Circulation 4.3 Gallery Plan: Media Distribution 4.4 Isometric View 4.5 Finishes 5.0 The Visitor Experience 5.1 Visuals of the Gallery 5.2 Accessibility 6.0 Consultation & Participation EXHIBITION DESIGN REPORT 3 Ratings from HMS Sphinx. In the back row, second left, is Able Seaman Joseph Chidwick who first spotted 6 Africans floating on an upturned tree, after they had escaped from a slave trader on the coast. The Navy’s impact has been felt around the world, in peace as well as war. Here, the ship’s Carpenter on HMS Sphinx sets an enslaved African free following his escape from a slave trader in The slave trader following his capture by a party of Royal Marines and seamen. the Persian Gulf, 1907. 4 EXHIBITION DESIGN REPORT 1.0 Executive Summary 1.0 Executive Summary Enabling people to learn, enjoy and engage with the story of the Royal Navy and understand its impact in making the modern world. -

Alternative Naval Force Structure

Alternative Naval Force Structure A compendium by CIMSEC Articles By Steve Wills · Javier Gonzalez · Tom Meyer · Bob Hein · Eric Beaty Chuck Hill · Jan Musil · Wayne P. Hughes Jr. Edited By Dmitry Filipoff · David Van Dyk · John Stryker 1 Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................ 3 The Perils of Alternative Force Structure ................................................... 4 By Steve Wills UnmannedCentric Force Structure ............................................................... 8 By Javier Gonzalez Proposing A Modern High Speed Transport – The Long Range Patrol Vessel ................................................................................................... 11 By Tom Meyer No Time To Spare: Drawing on History to Inspire Capability Innovation in Today’s Navy ................................................................................. 15 By Bob Hein Enhancing Existing Force Structure by Optimizing Maritime Service Specialization .............................................................................................. 18 By Eric Beaty Augment Naval Force Structure By Upgunning The Coast Guard .......................................................................................................... 21 By Chuck Hill A Fleet Plan for 2045: The Navy the U.S. Ought to be Building ..... 25 By Jan Musil Closing Remarks on Changing Naval Force Structure ....................... 31 By Wayne P. Hughes Jr. CIMSEC 22 www.cimsec.org -

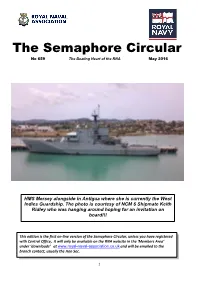

The Semaphore Circular No 659 the Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 659 The Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016 HMS Mersey alongside in Antigua where she is currently the West Indies Guardship. The photo is courtesy of NCM 6 Shipmate Keith Ridley who was hanging around hoping for an invitation on board!!! This edition is the first on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. April Open Day 2. New Insurance Credits 3. Blonde Joke 4. Service Deferred Pensions 5. Guess Where? 6. Donations 7. HMS Raleigh Open Day 8. Finance Corner 9. RN VC Series – T/Lt Thomas Wilkinson 10. Golf Joke 11. Book Review 12. Operation Neptune – Book Review 13. Aussie Trucker and Emu Joke 14. Legion D’Honneur 15. Covenant Fund 16. Coleman/Ansvar Insurance 17. RNPLS and Yard M/Sweepers 18. Ton Class Association Film 19. What’s the difference Joke 20. Naval Interest Groups Escorted Tours 21. RNRMC Donation 22. B of J - Paterdale 23. Smallie Joke 24. Supporting Seafarers Day Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General -

The Need for a New Naval History of the First World War James Goldrick

Corbett Paper No 7 The need for a New Naval History of The First World War James Goldrick The Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies November 2011 The need for a New Naval History of the First World War James Goldrick Key Points . The history of naval operations in the First World War urgently requires re- examination. With the fast approaching centenary, it will be important that the story of the war at sea be recognised as profoundly significant for the course and outcome of the conflict. There is a risk that popular fascination for the bloody campaign on the Western Front will conceal the reality that the Great War was also a maritime and global conflict. We understand less of 1914-1918 at sea than we do of the war on land. Ironically, we also understand less about the period than we do for the naval wars of 1793-1815. Research over the last few decades has completely revised our understanding of many aspects of naval operations. That work needs to be synthesized and applied to the conduct of the naval war as a whole. There are important parallels with the present day for modern maritime strategy and operations in the challenges that navies faced in exercising sea power effectively within a globalised world. Gaining a much better understanding of the issues of 1914-1918 may help cast light on some of the complex problems that navies must now master. James Goldrick is a Rear Admiral in the Royal Australian Navy and currently serving as Commander of the Australian Defence College. -

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. Donald Macintyre, Narvik (London: Evans, 1959), p. 15. 2. See Olav Riste, The Neutral Ally: Norway’s Relations with Belligerent Powers in the First World War (London: Allen and Unwin, 1965). 3. Reflections of the C-in-C Navy on the Outbreak of War, 3 September 1939, The Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs, 1939–45 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 37–38. 4. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 10 October 1939, in ibid. p. 47. 5. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 8 December 1939, Minutes of a Conference with Herr Hauglin and Herr Quisling on 11 December 1939 and Report of the C-in-C Navy, 12 December 1939 in ibid. pp. 63–67. 6. MGFA, Nichols Bohemia, n 172/14, H. W. Schmidt to Admiral Bohemia, 31 January 1955 cited by Francois Kersaudy, Norway, 1940 (London: Arrow, 1990), p. 42. 7. See Andrew Lambert, ‘Seapower 1939–40: Churchill and the Strategic Origins of the Battle of the Atlantic, Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 17, no. 1 (1994), pp. 86–108. 8. For the importance of Swedish iron ore see Thomas Munch-Petersen, The Strategy of Phoney War (Stockholm: Militärhistoriska Förlaget, 1981). 9. Churchill, The Second World War, I, p. 463. 10. See Richard Wiggan, Hunt the Altmark (London: Hale, 1982). 11. TMI, Tome XV, Déposition de l’amiral Raeder, 17 May 1946 cited by Kersaudy, p. 44. 12. Kersaudy, p. 81. 13. Johannes Andenæs, Olav Riste and Magne Skodvin, Norway and the Second World War (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1966), p. -

Primary Source and Background Documents D

Note: Original spelling is retained for this document and all that follow. Appendix 1: Primary source and background documents Document No. 1: Germany's Declaration of War with Russia, August 1, 1914 Presented by the German Ambassador to St. Petersburg The Imperial German Government have used every effort since the beginning of the crisis to bring about a peaceful settlement. In compliance with a wish expressed to him by His Majesty the Emperor of Russia, the German Emperor had undertaken, in concert with Great Britain, the part of mediator between the Cabinets of Vienna and St. Petersburg; but Russia, without waiting for any result, proceeded to a general mobilisation of her forces both on land and sea. In consequence of this threatening step, which was not justified by any military proceedings on the part of Germany, the German Empire was faced by a grave and imminent danger. If the German Government had failed to guard against this peril, they would have compromised the safety and the very existence of Germany. The German Government were, therefore, obliged to make representations to the Government of His Majesty the Emperor of All the Russias and to insist upon a cessation of the aforesaid military acts. Russia having refused to comply with this demand, and having shown by this refusal that her action was directed against Germany, I have the honour, on the instructions of my Government, to inform your Excellency as follows: His Majesty the Emperor, my august Sovereign, in the name of the German Empire, accepts the challenge, and considers himself at war with Russia. -

60 Years of Marine Nuclear Power: 1955

Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 - 2018 Part 4: Europe & Canada Peter Lobner July 2018 1 Foreword In 2015, I compiled the first edition of this resource document to support a presentation I made in August 2015 to The Lyncean Group of San Diego (www.lynceans.org) commemorating the 60th anniversary of the world’s first “underway on nuclear power” by USS Nautilus on 17 January 1955. That presentation to the Lyncean Group, “60 years of Marine Nuclear Power: 1955 – 2015,” was my attempt to tell a complex story, starting from the early origins of the US Navy’s interest in marine nuclear propulsion in 1939, resetting the clock on 17 January 1955 with USS Nautilus’ historic first voyage, and then tracing the development and exploitation of marine nuclear power over the next 60 years in a remarkable variety of military and civilian vessels created by eight nations. In July 2018, I finished a complete update of the resource document and changed the title to, “Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 – 2018.” What you have here is Part 4: Europe & Canada. The other parts are: Part 1: Introduction Part 2A: United States - Submarines Part 2B: United States - Surface Ships Part 3A: Russia - Submarines Part 3B: Russia - Surface Ships & Non-propulsion Marine Nuclear Applications Part 5: China, India, Japan and Other Nations Part 6: Arctic Operations 2 Foreword This resource document was compiled from unclassified, open sources in the public domain. I acknowledge the great amount of work done by others who have published material in print or posted information on the internet pertaining to international marine nuclear propulsion programs, naval and civilian nuclear powered vessels, naval weapons systems, and other marine nuclear applications. -

Download the Full PDF Here

THE PHILADELPHIA PAPERS A Publication of the Foreign Policy Research Institute GREAT WAR AT SEA: REMEMBERING THE BATTLE OF JUTLAND by John H. Maurer May 2016 13 FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE THE PHILADELPHIA PAPERS, NO. 13 GREAT WAR AT SEA: REMEMBERING THE BATTLE OF JUTLAND BY JOHN H. MAURER MAY 2016 www.fpri.org 1 THE PHILADELPHIA PAPERS ABOUT THE FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE Founded in 1955 by Ambassador Robert Strausz-Hupé, FPRI is a non-partisan, non-profit organization devoted to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the development of policies that advance U.S. national interests. In the tradition of Strausz-Hupé, FPRI embraces history and geography to illuminate foreign policy challenges facing the United States. In 1990, FPRI established the Wachman Center, and subsequently the Butcher History Institute, to foster civic and international literacy in the community and in the classroom. ABOUT THE AUTHOR John H. Maurer is a Senior Fellow of the Foreign Policy Research Institute. He also serves as the Alfred Thayer Mahan Professor of Sea Power and Grand Strategy at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone, and do not represent the settled policy of the Naval War College, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Foreign Policy Research Institute 1528 Walnut Street, Suite 610 • Philadelphia, PA 19102-3684 Tel. 215-732-3774 • Fax 215-732-4401 FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE 2 Executive Summary This essay draws on Maurer’s talk at our history institute for teachers on America’s Entry into World War I, hosted and cosponsored by the First Division Museum at Cantigny in Wheaton, IL, April 9-10, 2016. -

Defeating the U-Boat Inventing Antisubmarine Warfare NEWPORT PAPERS

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 36 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Defeating the U-boat Inventing Antisubmarine Warfare NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT S NA N E V ES AV T AT A A A L L T T W W S S A A D D R R E E C C T T I I O O L N L N L L U U E E E E G G H H E E T T I I VIRIBU VOIRRIABU OR A S CT S CT MARI VI MARI VI 36 Jan S. Breemer Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen U.S. GOVERNMENT Cover OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE This perspective aerial view of Newport, Rhode Island, drawn and published by Galt & Hoy of New York, circa 1878, is found in the American Memory Online Map Collections: 1500–2003, of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C. The map may be viewed at http://hdl.loc.gov/ loc.gmd/g3774n.pm008790. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. ISBN 978-1-884733-77-2 is for this U.S. Government Printing Office Official Edition only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Govern- ment Printing Office requests that any reprinted edi- tion clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The logo of the U.S. Naval War College (NWC), Newport, Rhode Island, authenticates Defeating the U- boat: Inventing Antisubmarine Warfare, by Jan S. -

The Taiidan Empire Fleet Rules

1 The Taiidan Empire Fleet Rules Homeworld Systems ships follow all of the rules found in the Battlefleet Gothic core rulebook, except for where specified below: Minimal Crew Homeworld Systems ships have little in the way of crew, as the majority of their ships are automated and AI-driven. Combined with a lack of training, this makes their crew distinctly incapable of taking the fight to the enemy in-person. -Unless otherwise specified, Homeworld Ships may never perform Boarding Actions, nor Hit and Run actions. They may still defend against such actions, if applicable. Crippled Status Homeworld ships rely heavily on automation and redundant systems, causing them to continue fighting at a higher level than one would expect, even as they sustain crippling damage. Homeworld ships, when reduced to 50% of their starting Hit Points, suffer the following effects: -Speed reduced by 5cm -Mass Driver battery strength reduced by 25% -Ion Beams are not effected by crippling Otherwise, their ships are unaffected by Crippled Status. Wide-Band Sensors Ships of the Homeworld Systems mount numerous banks of extremely advanced sensor systems, a holdover from their days of wandering the galaxy, looking for a home. These sensors are extremely adept at picking out the smallest fluctuation in space, and greatly assist the ship in both maneuvering and combat. This has proven extremely useful when dealing with the profusion of astrological phenomena, and the more slippery opponents like the Eldar. These have the following benefits: -All Homeworld ships apply a -1 modifier to any roll on either the Eldar Holofield or Dark Eldar Shadowfield chart, when rolling to see if their weapons have struck the target. -

Critical Engagement: Irish Republicanism, Memory Politics

Critical Engagement Critical Engagement Irish republicanism, memory politics and policing Kevin Hearty LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS First published 2017 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2017 Kevin Hearty The right of Kevin Hearty to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available print ISBN 978-1-78694-047-6 epdf ISBN 978-1-78694-828-1 Typeset by Carnegie Book Production, Lancaster Contents Acknowledgements vii List of Figures and Tables x List of Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Understanding a Fraught Historical Relationship 25 2 Irish Republican Memory as Counter-Memory 55 3 Ideology and Policing 87 4 The Patriot Dead 121 5 Transition, ‘Never Again’ and ‘Moving On’ 149 6 The PSNI and ‘Community Policing’ 183 7 The PSNI and ‘Political Policing’ 217 Conclusion 249 References 263 Index 303 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements This book has evolved from my PhD thesis that was undertaken at the Transitional Justice Institute, University of Ulster (TJI). When I moved to the University of Warwick in early 2015 as a post-doc, my plans to develop the book came with me too. It represents the culmination of approximately five years of research, reading and (re)writing, during which I often found the mere thought of re-reading some of my work again nauseating; yet, with the encour- agement of many others, I persevered. -

The Battlefleet Gothic Additional Ships Compendium the Battlefleet

THE BATTLEFLEET GOTHIC ADDITIONAL SHIPS COMPENDIUM - 1 The Battlefleet Gothic Additional Ships Compendium Additional rules published in White Dwarf, BFG Magazine and other Black Library books. Compiled by Thibault JABOULEY Imperial Ramilies Class Star Fort 875 pts.............................................................................3 Imperial Apocalypse Class Battleship 375 pts ......................................................................7 Imperial Invincible Class Fast Battleship 290 pts..................................................................8 Imperial Nemesis Class Fleet Carrier 400 pts.......................................................................9 Imperial Oberon Class Battleship 335 pts...........................................................................10 Imperial Vanquisher Class Battleship 340 pts.....................................................................11 Imperial Victory Class Battleship 360 pts............................................................................12 Imperial Avenger Class Grand Cruiser 220 pts...................................................................13 Imperial Exorcist Class Grand Cruiser 230 pts ...................................................................14 Imperial / Chaos Furious Class Grand Cruiser 265 pts......................................................15 Imperial / Chaos Vengeance Class Grand Cruiser 230 pts................................................17 Imperial Armaggedon Class Battlecruiser 235 pts ..............................................................18