Lepidoptera: Macroheterocera) Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fauna Lepidopterologica Volgo-Uralensis" 150 Years Later: Changes and Additions

©Ges. zur Förderung d. Erforschung von Insektenwanderungen e.V. München, download unter www.zobodat.at Atalanta (August 2000) 31 (1/2):327-367< Würzburg, ISSN 0171-0079 "Fauna lepidopterologica Volgo-Uralensis" 150 years later: changes and additions. Part 5. Noctuidae (Insecto, Lepidoptera) by Vasily V. A n ik in , Sergey A. Sachkov , Va d im V. Z o lo t u h in & A n drey V. Sv ir id o v received 24.II.2000 Summary: 630 species of the Noctuidae are listed for the modern Volgo-Ural fauna. 2 species [Mesapamea hedeni Graeser and Amphidrina amurensis Staudinger ) are noted from Europe for the first time and one more— Nycteola siculana Fuchs —from Russia. 3 species ( Catocala optata Godart , Helicoverpa obsoleta Fabricius , Pseudohadena minuta Pungeler ) are deleted from the list. Supposedly they were either erroneously determinated or incorrect noted from the region under consideration since Eversmann 's work. 289 species are recorded from the re gion in addition to Eversmann 's list. This paper is the fifth in a series of publications1 dealing with the composition of the pres ent-day fauna of noctuid-moths in the Middle Volga and the south-western Cisurals. This re gion comprises the administrative divisions of the Astrakhan, Volgograd, Saratov, Samara, Uljanovsk, Orenburg, Uralsk and Atyraus (= Gurjev) Districts, together with Tataria and Bash kiria. As was accepted in the first part of this series, only material reliably labelled, and cover ing the last 20 years was used for this study. The main collections are those of the authors: V. A n i k i n (Saratov and Volgograd Districts), S. -

(Crone Et Al.) S1. List of Studies with Movement In

Supplementary material: Mixed use landscapes can promote range expansion (Crone et al.) S1. List of studies with movement in high- and low-quality environments 1 Allema, B., van der Werf, W., van Lenteren, J. C., Hemerik, L. & Rossing, W. A. H. Movement behaviour of the carabid beetle Pterostichus melanarius in crops and at a habitat interface explains patterns of population redistribution in the field. PLoS One 9 (2014). 2 Avgar, T., Mosser, A., Brown, G. S. & Fryxell, J. M. Environmental and individual drivers of animal movement patterns across a wide geographical gradient. J. Anim. Ecol. 82, 96-106 (2013). 3 Brouwers, N. C. & Newton, A. C. Movement analyses of wood cricket (Nemobius sylvestris) (Orthoptera: Gryllidae). Bulletin of Entomological Research 100, 623-634 (2010). 4 Brown, L. M. et al. Using animal movement behavior to categorize land cover and predict consequences for connectivity and patch residence times. Landscape Ecol 32, 1657-1670 (2017). 5 Capinera, J. L. & Barbosa, P. Dispersal of first-instar gypsy moth larvae in relation to population quality. Oecologia 26, 53-64 (1976). 6 Cartar, R. V. & Real, L. A. Habitat structure and animal movement: the behaviour of bumble bees in uniform and random spatial resource distributions. Oecologia 112, 430- 434 (1997). 7 Chapman, D. S., Dytham, C. & Oxford, G. S. Landscape and fine-scale movements of a leaf beetle: the importance of boundary behaviour. Oecologia 154, 55-64 (2007). 8 Claussen, D. L., Finkler, M. S. & Smith, M. M. Thread trailing of turtles: methods for evaluating spatial movements and pathway structure. Canadian Journal of Zoology 75, 2120-2128 (1997). -

Insektenkasten Mit Eulenfaltern

Insektenkasten mit Eulenfaltern Kasten mit verschiedenen Arten von Eulenfaltern (Noctuidae) Maße: 40 x 30 x 6 cm Inventarnummer: ohne Aus der Insektensammlung des Departments für Evolutionsbiologie „Der erste Grad der Weisheit, sagt der Ritter v. Linné [1767, p. 12], ist das Erkenntniß der Dinge. Dieses Erkenntniß besteht in einem wahren Begriffe der Gegenstände, vermöge dessen Aehnliche von Unähnlichen durch eigene vom Schöpfer ihnen aufgedrückte Kennzeichen unterschieden werden. Wer dieses Kenntniß andern mittheilen will, muß allen verschiedenen Dingen eigene Namen geben, die niemal vermenget werden müßen. Denn mit den Namen fällt auch das Erkenntniß der Dinge.“ (Denis & Schiffermüller 1776, p. 23) Diese Feststellung Carl von Linnés (1707–1778), getroffen in der zwölften Auflage seines Hauptwerkes Systema naturae, fand als zentraler Gedanke Eingang in ein für die europäische Schmetterlingskunde grundlegendes Werk: das von Michael Denis (1729– 1800) und Ignaz Schiffermüller (1727–1806) verfasste „Systematische Verzeichniß der Schmetterlinge der Wienergegend“ (1 Aufl. 1775, 2 Aufl. 1776). Dieses Werk stellt eines der frühesten, mit dem Bemühen um Vollständigkeit angelegten Werke zur Schmetterlingsfauna eines geographisch klar umrissenen Gebietes dar. Das „Nebenprodukt“ dieser umfassenden Bestandsaufnahme war die Beschreibung einer sehr großen Zahl von damals der Wissenschaft noch unbekannten Arten aus Wien und Umgebung. Als Ausgangspunkt für ihre Bearbeitung diente den beiden Jesuiten Denis und Schiffermüller – beide Lehrer am Wiener Theresianum – eine umfangreiche selbst angelegte Schmetterlingssammlung. Auch an der Universität Wien wurde im darauffolgenden 19. Jahrhundert damit begonnen, eine Schmetterlingssammlung anzulegen (Salvini-Plawen & Mizzaro 1999, Waitzbauer 2012), die – so wie auch schon die Sammlung von Denis und Schiffermüller und ganz im Sinne des eingangs zitierten Linnés – primär als Lehrsammlung zur Vermittlung von Arten- und Formenkenntnis konzipiert war. -

Moths of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge

MOTHS OF UMATILLA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE: Results from 10 sites Sampled May 22-23, 2017 Dana Ross 1005 NW 30th Street Corvallis, OR 97330 (541) 758-3006 [email protected] SUMMARY Macro-moths were sampled from the Umatilla National Wildlife Refuge for a third time 22-23 May, 2017 as part of an ongoing pollinator inventory. Blacklight traps were deployed for a single night at ten sites representative of major plant communities in the McCormack and Paterson Units. A grand total of 331 specimens and 36 moth species were sampled. Of those, 17 species (47%) were documented from the refuge for the first time. In a somewhat larger geographical context, 21 species were recorded for the first (8), second (7) or third (6) time from Morrow County, Oregon while 4 species were documented for the first (1) or second (3) time from Benton County, Washington. INTRODUCTION National Wildlife Refuges protect important habitats for many plant and animal species. Refuge inventories have frequently included plants, birds and mammals, but insects - arguably the most abundant and species-rich group in any terrestrial habitat - have largely been ignored. Small size, high species richness and a lack of identification resources have all likely contributed to their being overlooked. Certain groups such as moths, however, can be easily and inexpensively sampled using light traps and can be identified by regional moth taxonomists. Once identified, many moth species can be tied to known larval hostplant species at a given site, placing both insect and plant within a larger ecological context. Moths along with butterflies belong to the insect Order Lepidoptera. -

Preliminary Ecological Appraisal Slyne-With-Hest, Lancaster

LANCASTER SITE ALLOCATION – SLYNE-WITH-HEST PRELIMINARY ECOLOGICAL APPRAISAL SLYNE-WITH-HEST, LANCASTER Provided for: Lancaster City Council Date: February 2016 Provided by: The Greater Manchester Ecology Unit Clarence Arcade Stamford Street Ashton-under-Lyne Tameside OL6 7PT Tel: 0161 342 4409 LSA – 4 FEBRUARY 2016 LANCASTER SITE ALLOCATION - SLYNE-WITH-HEST QUALITY ASSURANCE Author Suzanne Waymont CIEEM Checked By Stephen Atkins Approved By Derek Richardson Version 1.0 Draft for Comment Reference LSA - 4 The survey was carried out in accordance with the Phase 1 habitat assessment methods (JNCC 2010) and Guidelines for Preliminary Ecological Appraisal (CIEEM 2013). All works associated with this report have been undertaken in accordance with the Code of Professional Conduct for the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management. (www.cieem.org.uk) LSA – 4 FEBRUARY 2016 LANCASTER SITE ALLOCATION - SLYNE-WITH-HEST CONTENTS SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 SURVEY BRIEF 1.2 SITE LOCATION & PROPOSAL 1.3 PERSONNEL 2 LEGISLATION AND POLICY 3 METHODOLOGY 3.1 DESK STUDY 3.2 FIELD SURVEY 3.3 SURVEY LIMITATIONS 4 BASELINE ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS 4.1 DESKTOP SEARCH 4.2 SURVEY RESULTS 5 ECOLOGICAL CONSTRAINTS – IMPLICATIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS 6 CONCLUSIONS REFERENCES APPENDIX 1 – DATA SEARCH RESULTS APPENDIX 2 – DESIGNATED SITES APPENDIX 3 – BIOLOGICAL HERITAGE SITES LSA – 4 FEBRUARY 2016 LANCASTER SITE ALLOCATION - SLYNE-WITH-HEST SUMMARY • A Preliminary Ecological Appraisal was commissioned by Lancaster City Council to identify possible ecological constraints that could affect the development of 8 sites and areas currently being considered as new site allocations under its Local Plan. This report looks at one of these sites: Slyne-with-Hest. -

England Biodiversity Indicators 2020

4a. Status of UK priority species: relative abundance England Biodiversity Indicators 2020 This documents supports 4a. Status of UK priority species: relative abundance Technical background document Fiona Burns, Tom August, Mark Eaton, David Noble, Gary Powney, Nick Isaac, Daniel Hayhow For further information on 4a. Status of UK priority species: relative abundance visit https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/england-biodiversity-indicators 1 4a. Status of UK priority species: relative abundance Indicator 4a. Status of UK priority species: relative abundance Technical background document, 2020 NB this paper should be read together with 4b Status of UK Priority Species; distribution which presents a companion statistic based on time series on frequency of occurrence (distribution) of priority species. 1. Introduction The adjustments to the UK biodiversity indicators set as a result of the adoption of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity (including the Aichi Targets) at the 10th Conference of Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity mean there is a need to report progress against Aichi Target 12: Target 12: By 2020 the extinction of known threatened species has been prevented and their conservation status, particularly of those most in decline, has been improved and sustained. Previously, the UK biodiversity indicator for threatened species used lead partner status assessments on the status of priority species from 3-yearly UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) reporting rounds. As a result of the devolution of biodiversity strategies to the UK's 4 nations, there is no longer reporting at the UK level of the status of species previously listed by the BAP process. This paper presents a robust indicator of the status of threatened species in the UK, with species identified as conservation priorities being taken as a proxy for threatened species. -

Schutz Des Naturhaushaltes Vor Den Auswirkungen Der Anwendung Von Pflanzenschutzmitteln Aus Der Luft in Wäldern Und Im Weinbau

TEXTE 21/2017 Umweltforschungsplan des Bundesministeriums für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit Forschungskennzahl 3714 67 406 0 UBA-FB 002461 Schutz des Naturhaushaltes vor den Auswirkungen der Anwendung von Pflanzenschutzmitteln aus der Luft in Wäldern und im Weinbau von Dr. Ingo Brunk, Thomas Sobczyk, Dr. Jörg Lorenz Technische Universität Dresden, Fakultät für Umweltwissenschaften, Institut für Forstbotanik und Forstzoologie, Tharandt Im Auftrag des Umweltbundesamtes Impressum Herausgeber: Umweltbundesamt Wörlitzer Platz 1 06844 Dessau-Roßlau Tel: +49 340-2103-0 Fax: +49 340-2103-2285 [email protected] Internet: www.umweltbundesamt.de /umweltbundesamt.de /umweltbundesamt Durchführung der Studie: Technische Universität Dresden, Fakultät für Umweltwissenschaften, Institut für Forstbotanik und Forstzoologie, Professur für Forstzoologie, Prof. Dr. Mechthild Roth Pienner Straße 7 (Cotta-Bau), 01737 Tharandt Abschlussdatum: Januar 2017 Redaktion: Fachgebiet IV 1.3 Pflanzenschutz Dr. Mareike Güth, Dr. Daniela Felsmann Publikationen als pdf: http://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen ISSN 1862-4359 Dessau-Roßlau, März 2017 Das diesem Bericht zu Grunde liegende Vorhaben wurde mit Mitteln des Bundesministeriums für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit unter der Forschungskennzahl 3714 67 406 0 gefördert. Die Verantwortung für den Inhalt dieser Veröffentlichung liegt bei den Autorinnen und Autoren. UBA Texte Entwicklung geeigneter Risikominimierungsansätze für die Luftausbringung von PSM Kurzbeschreibung Die Bekämpfung -

Noctuid Moth (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae) Communities in Urban Parks of Warsaw

POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES • INSTITUTE OF ZOOLOGY MEMORABILIA ZOOLOGICA MEMORABILIA ZOOL. 42 125-148 1986 GRAŻYNA WINIARSKA NOCTUID MOTH (LEPIDOPTERA, NOCTUIDAE) COMMUNITIES IN URBAN PARKS OF WARSAW ABSTRACT A total of 40 noctuid moth species were recorded in four parks of Warsaw. Respective moth communities consisted of a similar number of species (17—25), but differed in their abundance index (3.5 —7.9). In all the parks, the dominant species were Autographa gamma and Discrestra trifolii. The subdominant species were represented by Acronicta psi, Trachea atriplicis, Mamestra suasa, Mythimna pallens, and Catocala nupta. There were differences in the species composition and dominance structure among noctuid moth communities in urban parks, suburban linden- oak-hornbeam forest, and natural linden-oak-hornbeam forest. In the suburban and natural linden-oak-hornbeam forests, the number of species was higher by 40% and their abundance wao 5 — 9 times higher than in the urban parks. The species predominating in parks occurred in very low numbers in suburban and natural habitats. Only T. atriplicis belonged to the group of most abundant species in all the habitats under study. INTRODUCTION In recent years, the interest of ecologists in urban habitats has been increasing as they proved to be rich in plant and animal species. The vegetation of urban green areas is sufficiently well known since its species composition and spatial structure are shaped by gardening treatment. But the fauna of these areas is poorly known, and regular zoological investigations in urban green areas were started not so long ago, when urban green was recognized as one of the most important factors of the urban “natural” habitat (Ciborowski 1976). -

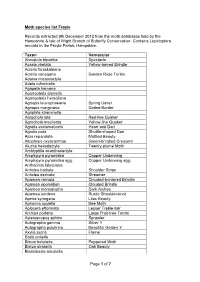

Page 1 of 7 Moth Species List Froyle Records

Moth species list Froyle Records extracted 9th December 2012 from the moth databases held by the Hampshire & Isle of Wight Branch of Butterfly Conservation. Contains Lepidoptera records in the Froyle Parish, Hampshire. Taxon Vernacular Abrostola tripartita Spectacle Acasis viretata Yellow-barred Brindle Acleris forsskaleana Acleris variegana Garden Rose Tortrix Adaina microdactyla Adela rufimitrella Agapeta hamana Agonopterix arenella Agonopterix heracliana Agriopis leucophaearia Spring Usher Agriopis marginaria Dotted Border Agriphila straminella Agrochola lota Red-line Quaker Agrochola macilenta Yellow-line Quaker Agrotis exclamationis Heart and Dart Agrotis puta Shuttle-shaped Dart Alcis repandata Mottled Beauty Allophyes oxyacanthae Green-brindled Crescent Alucita hexadactyla Twenty-plume Moth Amblyptilia acanthadactyla Amphipyra pyramidea Copper Underwing Amphipyra pyramidea agg. Copper Underwing agg. Anthophila fabriciana Anticlea badiata Shoulder Stripe Anticlea derivata Streamer Apamea crenata Clouded-bordered Brindle Apamea epomidion Clouded Brindle Apamea monoglypha Dark Arches Apamea sordens Rustic Shoulder-knot Apeira syringaria Lilac Beauty Aphomia sociella Bee Moth Aplocera efformata Lesser Treble-bar Archips podana Large Fruit-tree Tortrix Asteroscopus sphinx Sprawler Autographa gamma Silver Y Autographa pulchrina Beautiful Golden Y Axylia putris Flame Batia unitella Biston betularia Peppered Moth Biston strataria Oak Beauty Blastobasis adustella Page 1 of 7 Blastobasis lacticolella Cabera exanthemata Common Wave Cabera -

DE TTK 1949 Taxonomy and Systematics of the Eurasian

DE TTK 1949 Taxonomy and systematics of the Eurasian Craniophora Snellen, 1867 species (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Acronictinae) Az eurázsiai Craniophora Snellen, 1867 fajok taxonómiája és szisztematikája (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Acronictinae) PhD thesis Egyetemi doktori (PhD) értekezés Kiss Ádám Témavezető: Prof. Dr. Varga Zoltán DEBRECENI EGYETEM Természettudományi Doktori Tanács Juhász-Nagy Pál Doktori Iskola Debrecen, 2017. Ezen értekezést a Debreceni Egyetem Természettudományi Doktori Tanács Juhász-Nagy Pál Doktori Iskola Biodiverzitás programja keretében készítettem a Debreceni Egyetem természettudományi doktori (PhD) fokozatának elnyerése céljából. Debrecen, 2017. ………………………… Kiss Ádám Tanúsítom, hogy Kiss Ádám doktorjelölt 2011 – 2014. között a fent megnevezett Doktori Iskola Biodiverzitás programjának keretében irányításommal végezte munkáját. Az értekezésben foglalt eredményekhez a jelölt önálló alkotó tevékenységével meghatározóan hozzájárult. Az értekezés elfogadását javasolom. Debrecen, 2017. ………………………… Prof. Dr. Varga Zoltán A doktori értekezés betétlapja Taxonomy and systematics of the Eurasian Craniophora Snellen, 1867 species (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Acronictinae) Értekezés a doktori (Ph.D.) fokozat megszerzése érdekében a biológiai tudományágban Írta: Kiss Ádám okleveles biológus Készült a Debreceni Egyetem Juhász-Nagy Pál doktori iskolája (Biodiverzitás programja) keretében Témavezető: Prof. Dr. Varga Zoltán A doktori szigorlati bizottság: elnök: Prof. Dr. Dévai György tagok: Prof. Dr. Bakonyi Gábor Dr. Rácz István András -

Agrochola Circellaris Hufn

OchrOna ŚrOdOwiska i ZasObów naturalnych vOl. 28 nO 2(72): 41-45 EnvirOnmEntal PrOtEctiOn and natural rEsOurcEs 2017 dOi 10.1515 /OsZn-2017-0014 Jolanta Bąk-Badowska *, Ilona Żeber-Dzikowska**, Jarosław Chmielewski*** The impact of brick (Agrochola circellaris Hufn.) and owlet moths (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on the health of seeds of field elms (Ulmus minor Mill.) in the landscape parks of the Świętokrzyskie Province Wpływ zrzenicówki wiązowej (Agrochola circellaris Hufn.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) na zdrowotność nasion wiązu polnego (Ulmus minor Mill.) w parkach krajobrazowych województwa świętokrzyskiego *Dr hab. Jolanta Bąk-Badowska, Institute of Biology, The Jan Kochanowski ***Dr Jarosław Chmielewski, Institute of Environmental Protection-National University, Świętokrzyska 15 St., 25-406 Kielce, e-mail: [email protected] Research, Krucza 5/11d St., 00-548 Warsaw, e-mail: [email protected] **Dr hab. Ilona Żeber-Dzikowska, Prof. Nadzw., Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, The State School of Higher Professional Education in Płock, Gałczyńskiego 28 St., 09-400 Płock; Institute of Biology, The Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce, Świetokrzyska 15 St., 25-406 Kielce; e-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Ulmus minor, seed pests, Agrochola circellaris, stand density, landscape parks, the Świętokrzyskie Province Słowa kluczowe: Ulmus minor, szkodniki nasion, Agrochola circellaris, zwarcie drzewostanu, parki krajobrazowe, województwo świętokrzyskie Abstract Streszczenie In the period of 2012–2013, a research was conducted to W latach 2012-2013 przeprowadzono badania dotyczące investigate the insects damaging the seeds of field elm (Ulmus owadów uszkadzających nasiona wiązu polnego (Ulmus minor minor Mill.). The aim of the research was to specify the damages Mill.). -

Monitoring and Indicators of Forest Biodiversity in Europe – from Ideas to Operationality

Monitoring and Indicators of Forest Biodiversity in Europe – From Ideas to Operationality Marco Marchetti (ed.) EFI Proceedings No. 51, 2004 European Forest Institute IUFRO Unit 8.07.01 European Environment Agency IUFRO Unit 4.02.05 IUFRO Unit 4.02.06 Joint Research Centre Ministero della Politiche Accademia Italiana di University of Florence (JRC) Agricole e Forestali – Scienze Forestali Corpo Forestale dello Stato EFI Proceedings No. 51, 2004 Monitoring and Indicators of Forest Biodiversity in Europe – From Ideas to Operationality Marco Marchetti (ed.) Publisher: European Forest Institute Series Editors: Risto Päivinen, Editor-in-Chief Minna Korhonen, Technical Editor Brita Pajari, Conference Manager Editorial Office: European Forest Institute Phone: +358 13 252 020 Torikatu 34 Fax. +358 13 124 393 FIN-80100 Joensuu, Finland Email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.efi.fi/ Cover illustration: Vallombrosa, Augustus J C Hare, 1900 Layout: Kuvaste Oy Printing: Gummerus Printing Saarijärvi, Finland 2005 Disclaimer: The papers in this book comprise the proceedings of the event mentioned on the back cover. They reflect the authors' opinions and do not necessarily correspond to those of the European Forest Institute. © European Forest Institute 2005 ISSN 1237-8801 (printed) ISBN 952-5453-04-9 (printed) ISSN 14587-0610 (online) ISBN 952-5453-05-7 (online) Contents Pinborg, U. Preface – Ideas on Emerging User Needs to Assess Forest Biodiversity ......... 7 Marchetti, M. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 9 Session 1: Emerging User Needs and Pressures on Forest Biodiversity De Heer et al. Biodiversity Trends and Threats in Europe – Can We Apply a Generic Biodiversity Indicator to Forests? ................................................................... 15 Linser, S. The MCPFE’s Work on Biodiversity .............................................................