Mounted Archery in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USDA-NRSP8 Report for Horse Genome Committee for January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2014

USDA-NRSP8 Report for Horse Genome Committee for January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2014 Coordinators: Ernest Bailey (University of Kentucky); Molly McCue (University of Minnesota), Samantha Brooks (University of Florida) Workshop Chair for 2015 PAG meeting: Scott Dindot (Texas A&M University) Workshop Chair for 2016 PAG meeting: Ted Kalbfleisch (University of Louisville) Workshop Chair for 2017 PAG meeting: Carrie Finno (University of California, Davis) The workshop participants met on Saturday and Sunday, January 10-11, 2015 at the Plant and Animal Genome Conference in San Diego. Approximately 80 people attended the sessions with participants from at least 10 countries (USA, Brazil, China, Japan, Korea, Denmark, United Kingdom, Italy, Argentina, Ireland). Scott Dindot served as chair of the 2015 workshop. He will step down after this year and the next chair will be Ted Kalbfleisch. At the meeting, Carrie Finno was elected as vice-chair and will assist Ted Kalbfleisch in 2016 and assume full leadership of the workshop in 2017. Carrie J. Finno [email protected] 1 530 752 2739 Department of Population Health and Reproduction 280 CCAH University of California, Davis, CA 95616 Objective 1: Advance the status of reference genomes for all species, including basic annotation of worldwide genetic variation, by broad sequencing among different lines and breeds of animals. New Reference Genome Assembly Ted Kalbfleisch announced that the Morris Animal Foundation had selected for funding a proposal crafted by Ted, Jamie MacLeod and Ludovic Orlando for creating a new assembly of the reference sequence, the putative Ecab 3.0. Partial support for a postdoctoral student will come from USDA-NRSP8 coordinators’ funds. -

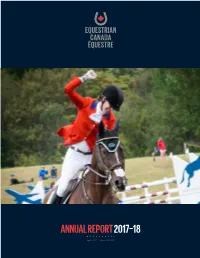

Annual Report 2017–18

ANNUAL REPORT 2017–18 April 1, 2017 — March 31, 2018 ABOUT EQUESTRIAN CANADA Equestrian Canada (EC) is the national governing body for equestrian sport and industry in Canada, with a mandate to represent, promote and advance all equine and equestrian interests. With over 16,000 Sport Licence Holders, 90,000 registered participants, 11 provincial/territorial sport organization partners and 10+ national equine affiliate organizations, EC is a significant contributor to the social, physical, emotional and economic wellbeing of the equestrian industry across Canada. OUR OUR VISION MISSION An aligned Canadian equestrian To lead, support, promote, govern and community that inspires and serves advocate for the equine and equestrian equestrians in their pursuit of personal community in Canada. excellence from pony to podium. OUR CORE VALUES WE BELIEVE IN: 04 05 Service Integrity Effectively and proactively Championing an serving the Canadian ethical, responsible and equestrian community to respectful approach to all support the advancement roles, levels and areas of of sport and industry. equestrian participation. 1 01 03 Excellence Partnership Upholding world- Generating a culture of class standards in all unity and collaboration our initiatives. across the equestrian community. 02 Welfare Protecting the safety and welfare of equestrians and equines equally. 2 Equestrian Canada Annual Report 2017-18 | 3 PROVINCIAL/TERRITORIAL PARTNERS Horse Council British Columbia Alberta Equestrian Federation Saskatchewan Horse Federation Manitoba Horse Council -

On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow 1

On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow 1 B.W. Kooi Groningen, The Netherlands 1983 1B.W. Kooi, On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow PhD-thesis, Mathematisch Instituut, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, The Netherlands (1983), Supported by ”Netherlands organization for the advancement of pure research” (Z.W.O.), project (63-57) 2 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Prefaceandsummary.............................. 5 1.2 Definitionsandclassifications . .. 7 1.3 Constructionofbowsandarrows . .. 11 1.4 Mathematicalmodelling . 14 1.5 Formermathematicalmodels . 17 1.6 Ourmathematicalmodel. 20 1.7 Unitsofmeasurement.............................. 22 1.8 Varietyinarchery................................ 23 1.9 Qualitycoefficients ............................... 25 1.10 Comparison of different mathematical models . ...... 26 1.11 Comparison of the mechanical performance . ....... 28 2 Static deformation of the bow 33 2.1 Summary .................................... 33 2.2 Introduction................................... 33 2.3 Formulationoftheproblem . 34 2.4 Numerical solution of the equation of equilibrium . ......... 37 2.5 Somenumericalresults . 40 2.6 A model of a bow with 100% shooting efficiency . .. 50 2.7 Acknowledgement................................ 52 3 Mechanics of the bow and arrow 55 3.1 Summary .................................... 55 3.2 Introduction................................... 55 3.3 Equationsofmotion .............................. 57 3.4 Finitedifferenceequations . .. 62 3.5 Somenumericalresults . 68 3.6 On the behaviour of the normal force -

CHANGE YOUR CALENDAR – TROT's ANNUAL DINNER And

-- Join TROT today! And encourage your riding buddies to join, too! January, 2017 Founded 1980 Number 219 INSIDE THIS ISSUE CHANGE YOUR CALENDAR – TROT's ANNUAL DINNER Annual Dinner – Venue Change 1 and SILENT AUCTION is still SATURDAY, MARCH 4, President's Message 1,3 2017, 6 PM, but at HOWARD COUNTY FAIRGROUNDS Horse World Expo, Jan 20-22 2 Help Trails-Speak to Your Legislators 3 (4-H building) from Gale Monahan and Priscilla Huffman 2017 Hunting Bills 3 TROT was to hold its Annual Meeting at the Fire Hall in Mt. Airy, as it has for several Howard County Bow Hunting Bills 4 years. However, TROT just learned that their renovations are delayed, so we had to Bun Bags in Anne Arundel County? 4 !nd another option. Happily, at the Howard County Fairgrounds (where TROT held its Possible Patapsco Greenway 4 annual dinners several years ago) Gale was able to arrange for the use of their 4-H building (the !rst building on the right by the #agpole as you enter the gate) on the New trails on Pepco Powerlines 5 originally planned date. This venue is conveniently near the intersection of Rt I-70 and Rt The Lisbon Horse Parade 5 32 (2210 Fairgrounds Rd., West Friendship, MD 21794). Check the Hunt Schedule 5 TROT Awarded Grant for Display 6 All are welcome to TROT's Annual Dinner (as always, a potluck) and Silent Auction, on Saturday, March 4, 2017, at 6:00 PM. But remember, this year it will be at Rachel Carson Park 6 the 4-H building of the Howard County Fairgrounds! [NOT in Mt. -

The Hokkaido Dialect

The Hokkaido Dialect A Standardising Dialect? Michael Kleander Bachelor Thesis Lund University Japanese Studies Centre for languages and literature Spring 2018 Supervisor Shinichiro Ishihara ABSTRACT This thesis explores the standardisation process of the Hokkaido Dialect, a Japanese variety spoken on Japan’s northernmost island. This dialect, in turn, will be compared to the island of Okinawa and its regional equivalent Uchinaa-Yamatoguchi. These islands are parallel to each other as they share similar historical and political events. To investigate the standardisation process and to be able to compare it to Uchinaa-Yamatoguchi, a survey was conducted. The aim of the survey was to investigate the usage of Hokkaido Dialect and the users’ attitudes towards the dialect among three different generations of Dosankos, people from Hokkaido. This study concludes that the standardisation process has been long in the making but that it has slowed down over time. Furthermore, evidence shows that the young generation is more positive about the Hokkaido Dialect than past generations. Based on this, one can conclude that rather than standardising, the dialect is stabilising. Keywords: Hokkaido Dialect, Dosanko, Kokugo, standardisation, language attitudes, language ideology, Standard Japanese, Common Japanese, Okinawa, Uchinaa-Yamatoguch II ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to personally extend my deepest gratitude for everyone that has helped me with my thesis. My deepest thanks to everyone who spread my survey around to Dosankos across Hokkaido, and of course to everyone who took the survey. I would further like to extend my thanks to Maya, I could not have done this thesis without her help, support and the materials I could not have accessed without her. -

COMPENDIO DOTES BETA.Pdf

Índice de Manuales Manual del Jugador Guía del Dungeon Master Manual del Jugador II Manual de Monstruos MJ2 MM El Aventurero Completo El Divino Completo El Arcano Completo El Combatiente Completo AC DC RC CC Draconomicón Especies Salvajes Héroes de Guerra Heroes of Horror D ES HG HH Faerûn: Guía del Jugador El Este Inaccesible Razas de Faerûn Escenario de Campaña GJF EI RF E Eberron: Guía del Jugador Libro de Obras Elevadas Libro de Oscuridad Vil Libris Mortis GJE OE OV LM Capítulo 1 – Presentación NOMBRE DE LA DOTE [TIPO DE DOTE] [CORRUPTA]: presentada en Heroes of Horror. Las dotes corruptas sólo Una descripción sencilla de lo que la dote hace o representa. pueden ser elegidas por aquellos que están corruptos, como se describe en el Requisitos: la puntuación mínima de característica, la dote o dotes, el apéndice. Ciertas dotes requieren una mayor corrupción que otras, o un tipo ataque base mínimo, la habilidad o el nivel de experiencia que se debe tener de corrupción específica (perversión o depravación). Cualquiera con una dote para poder adquirir esta dote. Este apartado no aparece en aquellas dotes que corrupta que reduzca su puntuación de corrupción por debajo de los carecen de requisito. Una dote puede tener más de un requisito. requisitos de la dote, pierde el acceso a esa dote. Sin embargo, no pierde la Beneficio: lo que la dote permite hacer al personaje (“tú” en la dote. No posee un espacio vacío para llenar con otra dote y recupera al descripción). Si un personaje tiene la misma dote más de una vez, sus instante el uso de la dote si alguna vez sube su nivel de corrupción al nivel beneficios no se apilan a no ser que en la descripción ponga otra cosa. -

Kyudo - the Way of the Bow

Kyudo - the Way of the Bow Centuries ago in Japan, archery was regarded as the highest discipline of the Samurai warrior. Then, as the bow lost its significance as a weapon of war, and under the influence of Buddhism, Shinto, Daoism and Confucianism, Japanese archery evolved into Kyudo, the "Way of the Bow", a powerful and highly refined contemplative practice. Kyudo, as taught by Kanjuro Shibata XX, is not a competitive sport and marksmanship is regarded as relatively unimportant. According to Shibata Sensei, a master of the Heki Ryu Bishu Chikurin-ha school of Kyudo, the ultimate goal of Kyudo is to polish the mind - the same as in sitting meditation. "One is not polishing one's shooting style or technique, but the mind. The dignity of shooting is the important point. This is how Kyudo differs from the common approach to Kanjuro Shibata Sensei at Kai. (ca. 1990) archery. In Kyudo there is no hope. Hope is not the point. The point is that through long which the practitioner has the opportunity to and genuine practice your natural dignity as see the mind more clearly. The target a human being comes out. This natural becomes a mirror which reflects the qualities dignity is already in you, but it is covered up of heart and mind at the moment of the by a lot of obstacles. When they are cleared arrow's release. away, your natural dignity is allowed to This distinguishes Kyudo from archery shine forth" - Shibata Sensei. where simply hitting the target is the goal. Chogyam Trungpa the renowned Tibetan Kyudo is "Standing meditation", and as meditation master said, "Through Kyudo one such, is a true contemplative art. -

Martial Arts from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia for Other Uses, See Martial Arts (Disambiguation)

Martial arts From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses, see Martial arts (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2011) Martial arts are extensive systems of codified practices and traditions of combat, practiced for a variety of reasons, including self-defense, competition, physical health and fitness, as well as mental and spiritual development. The term martial art has become heavily associated with the fighting arts of eastern Asia, but was originally used in regard to the combat systems of Europe as early as the 1550s. An English fencing manual of 1639 used the term in reference specifically to the "Science and Art" of swordplay. The term is ultimately derived from Latin, martial arts being the "Arts of Mars," the Roman god of war.[1] Some martial arts are considered 'traditional' and tied to an ethnic, cultural or religious background, while others are modern systems developed either by a founder or an association. Contents [hide] • 1 Variation and scope ○ 1.1 By technical focus ○ 1.2 By application or intent • 2 History ○ 2.1 Historical martial arts ○ 2.2 Folk styles ○ 2.3 Modern history • 3 Testing and competition ○ 3.1 Light- and medium-contact ○ 3.2 Full-contact ○ 3.3 Martial Sport • 4 Health and fitness benefits • 5 Self-defense, military and law enforcement applications • 6 Martial arts industry • 7 See also ○ 7.1 Equipment • 8 References • 9 External links [edit] Variation and scope Martial arts may be categorized along a variety of criteria, including: • Traditional or historical arts and contemporary styles of folk wrestling vs. -

2015 49Th Congress, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan

Applied ethology 2015: Ethology for sustainable society ISAE2015 Proceedings of the 49th Congress of the International Society for Applied Ethology 14-17 September 2015, Sapporo Hokkaido, Japan Ethology for sustainable society edited by: Takeshi Yasue Shuichi Ito Shigeru Ninomiya Katsuji Uetake Shigeru Morita Wageningen Academic Publishers Buy a print copy of this book at: www.WageningenAcademic.com/ISAE2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned. Nothing from this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a computerised system or published in any form or in any manner, including electronic, mechanical, reprographic or photographic, without prior written permission from the publisher: Wageningen Academic Publishers P.O. Box 220 EAN: 9789086862719 6700 AE Wageningen e-EAN: 9789086868179 The Netherlands ISBN: 978-90-8686-271-9 www.WageningenAcademic.com e-ISBN: 978-90-8686-817-9 [email protected] DOI: 10.3920/978-90-8686-817-9 The individual contributions in this publication and any liabilities arising from them remain First published, 2015 the responsibility of the authors. The publisher is not responsible for possible © Wageningen Academic Publishers damages, which could be a result of content The Netherlands, 2015 derived from this publication. ‘Sustainability for animals, human life and the Earth’ On behalf of the Organizing Committee of the 49th Congress of ISAE 2015, I would like to say fully welcome for all of you attendances to come to this Congress at Hokkaido, Japan! Now a day, our animals, that is, domestic, laboratory, zoo, companion, pest and captive animals or managed wild animals, and our life are facing to lots of problems. -

Setting up an Archery Range

Setting up an Archery Range 1 Updated March 2014 How to set up an archery range Content: Introduction ....................................................................................................... 2 Rules for designing a safe target archery range ............................................ 3-4 Outdoor shooting grounds ................................................................................. 4 Outdoor field orientation .................................................................................. 5 Outdoor field of play with safety zones ......................................................... 5-6 Outdoor field of play with reduced safety zones .......................................... 6-7 Indoor shooting range .................................................................................... 7-8 Field, Clout and Flight archery ..................................................................... 9-10 Setting out a competition target archery range ........................................ 10-12 Further reading ............................................................................................... 10 Introduction Archery is practiced all over the world. As with other sports, a special area is needed for practice and competition. Bow and arrows are part of the equipment of an archer; an archery range on a flat level field is needed for the safe practice of target archery. In field archery the ground is mostly far from level, however in this discipline there exist special rules for range layout. The specialist -

This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan William W

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale CEAS Occasional Publication Series Council on East Asian Studies 2007 This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan William W. Kelly Yale University Atsuo Sugimoto Kyoto University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ceas_publication_series Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, William W. and Sugimoto, Atsuo, "This Sporting Life: Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan" (2007). CEAS Occasional Publication Series. Book 1. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ceas_publication_series/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Council on East Asian Studies at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in CEAS Occasional Publication Series by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This Sporting Life Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan j u % g b Edited by William W. KELLY With SUGIMOTO Atsuo YALE CEAS OCCASIONAL PUBLICATIONS VOLUME 1 This Sporting Life Sports and Body Culture in Modern Japan yale ceas occasional publications volume 1 © 2007 Council on East Asian Studies, Yale University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permis- sion. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. -

Race Distance

odern horse racing in Japan had its beginnings in racing events that were organized by foreign residents of Yokohama in 1862. In 1861, when Japan was about to move from the feudal system into the Meiji Restoration, foreign residents living in Yokohama, predominantly British, introduced the first Western-style horse racing by establishing the Yokohama Race Club to Japan. Western style horse racing was held in foreign enclaves, and hence, unfortunately, very little is known or recorded about initial era in Japan’s modern horse racing history. At about the same time that the name of the Japanese central city was changed from Edo to Tokyo, Western-style horse racing began to be found in the major metropolitan cities across the country. In 1906, the government embarked on a policy which tacitly allowed to bet. This led to the introduction of modern horse racing featuring sales of betting tickets in Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka and other metropolitan cities, from which most racing operations benefited. However, this profitable system was short lived; two years later, the government prohibited betting and instituted a system of paying direct subsidies for prize money and other horse racing expenses. During this subsequent period of government-subsidized horse racing, prominent legislators, businessmen, as well as breeders, began active efforts to introduce a horse racing law. Eventually the government began to take proactive position to promote horse racing in order to expand breeding in Japan and to improve quality of the Japanese horses. In 1923, horse racing legislation, so greatly desired by the horse racing industry, was enacted and led to the formation of 11 racing clubs.