Sun-Bathing As a Thermo-Regulatory and in Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/11/2021 06:43:08AM Via Free Access 182 T

Bijdragen tot de Dierkunde, 56 (2): 181-204 — 1986 Microscopic identification of feathers and feather fragments of Palearctic birds by Tim G. Brom Institute of Taxonomic Zoology (Zoologisch Museum), University of Amsterdam, P.O. Box 20125, 1000 HC Amsterdam, The Netherlands much better and Abstract a assessment of the problem could suggest the most adequate preventive Using light microscopy, a method has been developed for measures. the identification of feathers and feather fragments col- of lected after collisions between birds and aircraft. Charac- LaHam (1967) started the application of the barbules of feathers described for 22 ters downy are microscopic investigation of scrapings collected orders of birds. The of in combination with the use a key of amino from engines, combined with the use macroscopic method of comparing feathers with bird skins acid of and able analysis protein residues, was in a museum collection results in identificationto order or to bird so that defective family level in 97% of the analysed bird strikes. Applica- diagnose strikes, could be into those tion of the method to other fields of biological research engines rapidly separated is discussed. including taxonomy due to either bird strikes or mechanical failures. The microscopic structure of feathers was Résumé first studied by Chandler (1916). He described of feathers of North the structure pennaceous Une méthode utilisant la microscopie optique a été mise l’identification des des American and found differences à point pour plumes et fragments birds, large de collectés des collisions oiseaux plume après entre et between different taxa. He also examined the avions. On décrit les caractères des barbules duveteuses downy barbules of a few species and provided des 22 ordres d’oiseaux. -

Eagle Hill, Kenya: Changes Over 60 Years

Scopus 34: 24–30, January 2015 Eagle Hill, Kenya: changes over 60 years Simon Thomsett Summary Eagle Hill, the study site of the late Leslie Brown, was first surveyed over 60 years ago in 1948. The demise of its eagle population was near-complete less than 50 years later, but significantly, the majority of these losses occurred in the space of a few years in the late 1970s. Unfortunately, human densities and land use changes are poor- ly known, and thus poor correlation can be made between that and eagle declines. Tolerant local attitudes and land use practices certainly played a significant role in protecting the eagles while human populations began to grow. But at a certain point it would seem that changed human attitudes and population density quickly tipped the balance against eagles. Introduction Raptors are useful in qualifying habitat and biodiversity health as they occupy high trophic levels (Sergio et al. 2005), and changes in their density reflect changes in the trophic levels that support them. In Africa, we know that raptors occur in greater diversity and abundance in protected areas such as the Matapos Hills, Zimbabwe (Macdonald & Gargett 1984; Hartley 1993, 1996, 2002 a & b), and Sabi Sand Reserve, South Africa (Simmons 1994). Although critically important, few draw a direct cor- relation between human effects on the environment and raptor diversity and density. The variables to consider are numerous and the conclusions unworkable due to dif- ferent holding-capacities, latitude, land fertility, seasonality, human attitudes, and different tolerances among raptor species to human disturbance. Although the concept of environmental effects caused by humans leading to rap- tor decline is attractive and is used to justify raptor conservation, there is a need for caution in qualifying habitat ‘health’ in association with the quantity of its raptor community. -

The Gambia: a Taste of Africa, November 2017

Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 A Tropical Birding “Chilled” SET DEPARTURE tour The Gambia A Taste of Africa Just Six Hours Away From The UK November 2017 TOUR LEADERS: Alan Davies and Iain Campbell Report by Alan Davies Photos by Iain Campbell Egyptian Plover. The main target for most people on the tour www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] p.1 Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 Red-throated Bee-eaters We arrived in the capital of The Gambia, Banjul, early evening just as the light was fading. Our flight in from the UK was delayed so no time for any real birding on this first day of our “Chilled Birding Tour”. Our local guide Tijan and our ground crew met us at the airport. We piled into Tijan’s well used minibus as Little Swifts and Yellow-billed Kites flew above us. A short drive took us to our lovely small boutique hotel complete with pool and lovely private gardens, we were going to enjoy staying here. Having settled in we all met up for a pre-dinner drink in the warmth of an African evening. The food was delicious, and we chatted excitedly about the birds that lay ahead on this nine- day trip to The Gambia, the first time in West Africa for all our guests. At first light we were exploring the gardens of the hotel and enjoying the warmth after leaving the chilly UK behind. Both Red-eyed and Laughing Doves were easy to see and a flash of colour announced the arrival of our first Beautiful Sunbird, this tiny gem certainly lived up to its name! A bird flew in landing in a fig tree and again our jaws dropped, a Yellow-crowned Gonolek what a beauty! Shocking red below, black above with a daffodil yellow crown, we were loving Gambian birds already. -

Estimations Relative to Birds of Prey in Captivity in the United States of America

ESTIMATIONS RELATIVE TO BIRDS OF PREY IN CAPTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA by Roger Thacker Department of Animal Laboratories The Ohio State University Columbus, Ohio 43210 Introduction. Counts relating to birds of prey in captivity have been accomplished in some European countries; how- ever, to the knowledge of this author no such information is available in the United States of America. The following paper consistsof data related to this subject collected during 1969-1970 from surveys carried out in many different direc- tions within this country. Methods. In an attempt to obtain as clear a picture as pos- sible, counts were divided into specific areas: Research, Zoo- logical, Falconry, and Pet Holders. It became obvious as the project advanced that in some casesthere was overlap from one area to another; an example of this being a falconer working with a bird both for falconry and research purposes. In some instances such as this, the author has used his own judgment in placing birds in specific categories; in other in- stances received information has been used for this purpose. It has also become clear during this project that a count of "pets" is very difficult to obtain. Lack of interest, non-coop- eration, or no available information from animal sales firms makes the task very difficult, as unfortunately, to obtain a clear dispersal picture it is from such sourcesthat informa- tion must be gleaned. However, data related to the importa- tion of birds' of prey as recorded by the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife is included, and it is felt some observa- tions can be made from these figures. -

Trade of Threatened Vultures and Other Raptors for Fetish and Bushmeat in West and Central Africa

Trade of threatened vultures and other raptors for fetish and bushmeat in West and Central Africa R. BUIJ,G.NIKOLAUS,R.WHYTOCK,D.J.INGRAM and D . O GADA Abstract Diurnal raptors have declined significantly in Introduction western Africa since the s. To evaluate the impact of traditional medicine and bushmeat trade on raptors, we ex- ildlife is exploited throughout West and Central amined carcasses offered at markets at sites (– stands WAfrica (Martin, ). The trade in bushmeat (wild- per site) in countries in western Africa during –. sourced meat) has been recognized as having a negative im- Black kite Milvus migrans andhoodedvultureNecrosyrtes pact on wildlife populations in forests and savannahs monachus together accounted for %of, carcasses com- (Njiforti, ; Fa et al., ; Lindsey et al., ), and it . prising species. Twenty-seven percent of carcasses were of is estimated billion kg of wild animal meat is traded an- species categorized as Near Threatened, Vulnerable or nually in Central Africa (Wilkie & Carpenter, ). In add- Endangered on the IUCN Red List. Common species were ition to being exploited for bushmeat, many animals are traded more frequently than rarer species, as were species hunted and traded specifically for use in traditional medi- with frequent scavenging behaviour (vs non-scavenging), gen- cine, also known as wudu, juju or fetish (Adeola, ). eralist or savannah habitat use (vs forest), and an Afrotropical The use of wildlife items for the treatment of a range of (vs Palearctic) breeding range. Large Afrotropical vultures physical and mental diseases, or to bring good fortune, were recorded in the highest absolute and relative numbers has been reported in almost every country in West and in Nigeria, whereas in Central Africa, palm-nut vultures Central Africa. -

Raptors in the East African Tropics and Western Indian Ocean Islands: State of Ecological Knowledge and Conservation Status

j. RaptorRes. 32(1):28-39 ¸ 1998 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. RAPTORS IN THE EAST AFRICAN TROPICS AND WESTERN INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS: STATE OF ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND CONSERVATION STATUS MUNIR VIRANI 1 AND RICHARD T. WATSON ThePeregrine Fund, Inc., 566 WestFlying Hawk Lane, Boise,1D 83709 U.S.A. ABSTRACT.--Fromour reviewof articlespublished on diurnal and nocturnal birds of prey occurringin Africa and the western Indian Ocean islands,we found most of the information on their breeding biology comesfrom subtropicalsouthern Africa. The number of published papers from the eastAfrican tropics declined after 1980 while those from subtropicalsouthern Africa increased.Based on our KnoM- edge Rating Scale (KRS), only 6.3% of breeding raptorsin the eastAfrican tropicsand 13.6% of the raptorsof the Indian Ocean islandscan be consideredWell Known,while the majority,60.8% in main- land east Africa and 72.7% in the Indian Ocean islands, are rated Unknown. Human-caused habitat alteration resultingfrom overgrazingby livestockand impactsof cultivationare the main threatsfacing raptors in the east African tropics, while clearing of foreststhrough slash-and-burnmethods is most important in the Indian Ocean islands.We describeconservation recommendations, list priorityspecies for study,and list areasof ecologicalunderstanding that need to be improved. I•y WORDS: Conservation;east Africa; ecology; western Indian Ocean;islands; priorities; raptors; research. Aves rapacesen los tropicos del este de Africa yen islasal oeste del Oc•ano Indico: estado del cono- cimiento eco16gicoy de su conservacitn RESUMEN.--Denuestra recopilacitn de articulospublicados sobre aves rapaces diurnas y nocturnasque se encuentran en Africa yen las islasal oeste del Octano Indico, encontramosque la mayoriade la informaci6n sobre aves rapacesresidentes se origina en la regi6n subtropical del sur de Africa. -

“CHAPUNGU: Nature, Man, and Myth” April 28 Through October 31, 2007 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

“CHAPUNGU: Nature, Man, and Myth” April 28 through October 31, 2007 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS “Chapungu: Nature, Man, and Myth” presents 23 monumental, hand-carved stone sculptures of people, animals, and creatures of legend created by artists from the African nation of Zimbabwe, many from the Shona tribe. The exhibition illustrates a traditional African family’s attitude and close bond to nature, illustrating their interdependence in an increasingly complex world and fragile environment. How does this exhibition differ from the one the Missouri Botanical Garden hosted in 2001? All but one of the sculptures in this exhibition have never been displayed at the Missouri Botanical Garden. “Chapungu: Custom and Legend, A Culture in Stone” made its U.S. debut here in 2001. Two large sculptures from that exhibition were acquired by the Garden: “Protecting the Eggs” by Damian Manuhwa, and the touching “Sole Provider” by Joe Mutasa. Both are located in the Azalea-Rhodendron Garden, near the tram shelter. “Sole Provider” was donated by the people of Zimbabwe and Chapungu Sculpture Park in memory of those who died during the September 11, 2001 tragedy. An opal stone sculpture from the 2001 exhibition – Biggie Kapeta’s “Chief Consults With Chapungu”– returns as a preview piece, installed outside the Ridgway Center in January. Many artists from the 2001 exhibition are represented by other works this time. How do you say Chapungu? What does it mean? Say “Cha-POONG-goo.” Chapungu is a metaphor for the Bateleur Eagle (Terathopius ecaudatus), a powerful bird of prey that can fly up to 300 miles in a day at 30 to 50 miles per hour. -

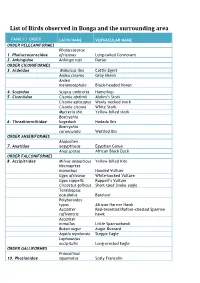

Birds Species in Bonga List

List of Birds observed in Bonga and the surrounding area FAMILY / ORDER LATIN NAME VERNACULAR NAME ORDER PELECANIFORMES Phalacrocorax 1. Phalacrocoracidae africanus Long-tailed Cormorant 2. Anhingidae Anhinga rufa Darter ORDER CICONIIFORMES 3. Ardeidae Bubulcus ibis Cattle Egret Ardea cinerea Grey Heron Ardea melanocephala Black-headed Heron 4. Scopidae Scopus umbretta Hamerkop 5. Ciconiidae Ciconia abdimii Abdim’s Stork Ciconia episcopus Wooly -necked stork Ciconia ciconia White Stork Mycteria ibis Yellow -billed stork Bostrychia 6. Threskiornithidae hagedash Hadada Ibis Bostrychia carunculata Wattled Ibis ORDER ANSERIFORMES Alopochen 7. Anatidae aegyptiacus Egyptian Goose Anas sparsa African Black Duck ORDER FALCONIFORMES 8. Accipitridae Milvus aegypticus Yellow -billed Kite Necrosyrtes monachus Hooded Vulture Gyps africanus White -backed Vulture Gyps ruppellii Ruppell’s Vulture Circaetus gallicus Short -toed Snake -eagle Terathopius ecaudatus Bateleur Polyboroides typus African Harrier Hawk Accipiter Red -breasted/Rufous -chested Sparrow rufiventris hawk Accipiter minullus Little Sparrowhawk Buteo augur Augur Buzzard Aquila nipalensis Steppe Eagle Lophoaetus occipitalis Long-crested Eagle ORDER GALLIFORMES Francolinus 10. Phasianidae squamatus Scaly Francolin FAMILY / ORDER LATIN NAME VERNACULAR NAME Francolinus castaneicollis Chestnut-napped Francolin ORDER GRUIFORMES Balearica 11. Gruidae pavonina Black Crowned Crane Bugeranus carunculatus Wattled crane Ruogetius 12. Rallidae rougetii Rouget’s Rail Podica 13. Heliornithidae senegalensis African Finfoot ORDER CHARADRIIFORMES 14. Scolopacidae Tringa ochropus Green Sandpiper Tringa hypolucos Common Sandpiper ORDER COLUMBIFORMES 15. Columbidae Columba guinea Speckled Pigeon Columba arquatrix African Olive Pigeon (Rameron Pigeon) Streptopelia lugens Dusky (Pink-breasted) Turtle Dove Streptopelia semitorquata Red-eyed Dove Turtur chalcospilos Emerald-spotted Wood Dove Turtur tympanistria Tambourine Dove ORDER CUCULIFORMES 17. Musophagidae Tauraco leucotis White -cheeked Turaco Centropus 18. -

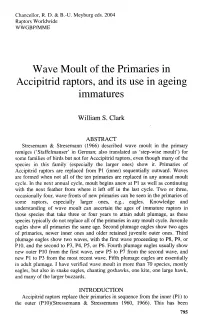

Wave Moult of the Primaries in Accipitrid Raptors, and Its Use in Ageing Immatures

Chancellor, R. D. & B.-U. Meyburg eds. 2004 Raptors Worldwide WWGBP/MME Wave Moult of the Primaries in Accipitrid raptors, and its use in ageing immatures William S. Clark ABSTRACT Stresemann & Stresemann (1966) described wave moult in the primary remiges ('Staffelmauser' in German; also translated as 'step-wise moult') for some families of birds but not for Acccipitrid raptors, even though many of the species in this family (especially the larger ones) show it. Primaries of Accipitrid raptors are replaced from Pl (inner) sequentially outward. Waves are formed when not all of the ten primaries are replaced in any annual moult cycle. In the next annual cycle, moult begins anew at Pl as well as continuing with the next feather from where it left off in the last cycle. Two or three, occasionally four, wave fronts of new primaries can be seen in the primaries of some raptors, especially larger ones, e.g., eagles. Knowledge and understanding of wave moult can ascertain the ages of immature raptors in those species that take three or four years to attain adult plumage, as these species typically do not replace all of the primaries in any moult cycle. Juvenile eagles show all primaries the same age. Second plumage eagles show two ages of primaries, newer inner ones and older retained juvenile outer ones. Third plumage eagles show two waves, with the first wave proceeding to P8, P9, or PIO, and the second to P3, P4, P5, or P6. Fourth plumage eagles usually show new outer PlO from the first wave, new P5 to P7 from the second wave, and new Pl to P3 from the most recent wave. -

Accipitridae Species Tree

Accipitridae I: Hawks, Kites, Eagles Pearl Kite, Gampsonyx swainsonii ?Scissor-tailed Kite, Chelictinia riocourii Elaninae Black-winged Kite, Elanus caeruleus ?Black-shouldered Kite, Elanus axillaris ?Letter-winged Kite, Elanus scriptus White-tailed Kite, Elanus leucurus African Harrier-Hawk, Polyboroides typus ?Madagascan Harrier-Hawk, Polyboroides radiatus Gypaetinae Palm-nut Vulture, Gypohierax angolensis Egyptian Vulture, Neophron percnopterus Bearded Vulture / Lammergeier, Gypaetus barbatus Madagascan Serpent-Eagle, Eutriorchis astur Hook-billed Kite, Chondrohierax uncinatus Gray-headed Kite, Leptodon cayanensis ?White-collared Kite, Leptodon forbesi Swallow-tailed Kite, Elanoides forficatus European Honey-Buzzard, Pernis apivorus Perninae Philippine Honey-Buzzard, Pernis steerei Oriental Honey-Buzzard / Crested Honey-Buzzard, Pernis ptilorhynchus Barred Honey-Buzzard, Pernis celebensis Black-breasted Buzzard, Hamirostra melanosternon Square-tailed Kite, Lophoictinia isura Long-tailed Honey-Buzzard, Henicopernis longicauda Black Honey-Buzzard, Henicopernis infuscatus ?Black Baza, Aviceda leuphotes ?African Cuckoo-Hawk, Aviceda cuculoides ?Madagascan Cuckoo-Hawk, Aviceda madagascariensis ?Jerdon’s Baza, Aviceda jerdoni Pacific Baza, Aviceda subcristata Red-headed Vulture, Sarcogyps calvus White-headed Vulture, Trigonoceps occipitalis Cinereous Vulture, Aegypius monachus Lappet-faced Vulture, Torgos tracheliotos Gypinae Hooded Vulture, Necrosyrtes monachus White-backed Vulture, Gyps africanus White-rumped Vulture, Gyps bengalensis Himalayan -

FOREWORD by KEITH L. BILDSTEIN and JEMIMA PARRY-JO Copyright © 2010 by Cornell University

FOREWORD BY KEITH L. BILDSTEIN AND JEMIMA PARRY-JO Copyright © 2010 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permis- sion in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, NewYork 14850. First published 2010 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The eagle watchers : observing and conserving raptors around the world / edited by Ruth E. Tingay and Todd E. Katzner ; foreword by Keith L. Bildstein and Jemima Parry-Jones, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8014-4873-7 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Eagles. 2. Eagles—Conservation. I. Tingay, Ruth E. II. Katxner, Todd E. III. Title. QL696.F32E22 2010 598.9'42—dc22 2009052785 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible sup- pliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly com- posed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Clothprinting 10 987654321 Contents Foreword xi Keith L. Bildstein and Jemima Parry-Jones Preface xiii Ruth E. Tingay and Todd E. Katzner 1 Eagle Diversity, Ecology, and Conservation 1 ToddE. Katzner and Ruth E. Tingay 2 New Guinea Harpy Eagle 26 Mark Watson (New Guinea) and Martin Gilbert (New Guinea) 3 GoldenEagle 40 Carol McIntyre (USA) andJeffWatson (Scotland) 4 Lesser Spotted Eagle 53 Bernd-U . -

Birdlife Naturekenya INTERNATIONAL the East Africa Natural Hlslory Society Scopus 30, October 2010 Contents

TOS 4-OI 8 ISSN 0250-4162 SCOPUS ^ z FEB j 2014 I A publication of the Bird Committee of the East Africa Natural History Society Edited by Mwangi Githiru Volume 30, October 2010 BirdLife NatureKenya INTERNATIONAL The East Africa Natural Hlslory Society Scopus 30, October 2010 Contents Maurice O. Ogoma, Broder Breckling, Hauke Reuter, Muchai Muchane and Mwangi Githiru. The birds of Gongoni Forest Reserve, South Coast, Kenya 1 Wanyoike Wamiti. Philista Malaki, Kamau Kimani, Nicodemus Nalianya, Chege Kariuki and Lawrence Wagura. The birds of Uaso Narok Forest Reserve, Central Kenya 12 Richard Ssemmanda and Derek Pomeroy. Scavenging birds of Kampala: 1973-2009 26 Jon Smallie and Munir Z. Virani. A preliminary assessment of the potential risks from electrical infrastructure to large birds in Kenya 32 Fred B. Munyekenye and Mwangi Githiru. A survey of the birds of Ol Donyo Sabuk National Park, Kenya 40 Short communications Donald A. TUrner. The status and habitats of two closely related and sympatric greenbuls: Ansorge's Andropadus ansorgei and Little Grey Andropadus gracilis 50 Donald A. Turner. Comments concerning Ostrich Struthio camelus populations in Kenya 52 Donald A. Turner. Comments concerning the status of the White-bellied Bustard race Eupodotis senegalensis erlangeri 54 Tiziano Londei. Typical Little Egrets Egretta garzetta mix with Dimorphic Egrets Egretta dimorpha on open coast in Tanzania 56 Donald A. Turner. The Egretta garzetta complex in East Africa: A case for one, two or three species 59 Donald a. Turner and Dale a. Zimmerman. Quailfinches Ortygospiza spp. in East Africa 63 Neil E. Baker. Recommendation to remove the Somali Bee-eater Merops revoilii from the Tanzania list 65 Neil E.