The Process of Awakening and Conversion to Buddhism Among Non-Mahar Communities in Maharashtra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reassessing Religion and Politics in the Life of Jagjivan Ram¯

religions Article Reassessing Religion and Politics in the Life of Jagjivan Ram¯ Peter Friedlander South and South East Asian Studies Program, School of Culture History and Language, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2600, Australia; [email protected] Received: 13 March 2020; Accepted: 23 April 2020; Published: 1 May 2020 Abstract: Jagjivan Ram (1908–1986) was, for more than four decades, the leading figure from India’s Dalit communities in the Indian National Congress party. In this paper, I argue that the relationship between religion and politics in Jagjivan Ram’s career needs to be reassessed. This is because the common perception of him as a secular politician has overlooked the role that his religious beliefs played in forming his political views. Instead, I argue that his faith in a Dalit Hindu poet-saint called Ravidas¯ was fundamental to his political career. Acknowledging the role that religion played in Jagjivan Ram’s life also allows us to situate discussions of his life in the context of contemporary debates about religion and politics. Jeffrey Haynes has suggested that these often now focus on whether religion is a cause of conflict or a path to the peaceful resolution of conflict. In this paper, I examine Jagjivan Ram’s political life and his belief in the Ravidas¯ ¯ı religious tradition. Through this, I argue that Jagjivan Ram’s career shows how political and religious beliefs led to him favoring a non-confrontational approach to conflict resolution in order to promote Dalit rights. Keywords: religion; politics; India; Congress Party; Jagjivan Ram; Ravidas;¯ Ambedkar; Dalit studies; untouchable; temple building 1. -

203Rd Anniversary of the Bhima-Koregaon Battle

203rd Anniversary of the Bhima-Koregaon Battle drishtiias.com/printpdf/203rd-anniversary-of-the-bhima-koregaon-battle Why in News The victory pillar (also known as Ranstambh or Jaystambh) in Bhima-Koregaon village (Pune district of Maharashtra) celebrated the 203rd anniversary of the Bhima- Koregaon battle of 1818 on 1st January, 2021. In 2018, incidents of violent clashes between Dalit and Maratha groups were registered during the celebration of the 200th anniversary of the Bhima-Koregaon battle. Key Points 1/2 Historical Background: A battle was fought in Bhima Koregaon between the Peshwa forces and the British on 1st January, 1818. The British army, which comprised mainly of Dalit soldiers, fought the upper caste-dominated Peshwa army. The British troops defeated the Peshwa army. Peshwa Bajirao II had insulted the Mahar community and terminated them from the service of his army. This caused them to side with the English against the Peshwa’s numerically superior army. Mahar, caste-cluster, or group of many endogamous castes, living chiefly in Maharashtra state and in adjoining states. They mostly speak Marathi, the official language of Maharashtra. They are officially designated Scheduled Castes. The defeat of Peshwa army was considered to be a victory against caste-based discrimination and oppression. It was one of the last battles of the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817-18), which ended the Peshwa domination. Babasaheb Ambedkar’s visit to the site on 1st January, 1927, revitalised the memory of the battle for the Dalit community, making it a rallying point and an assertion of pride. The Victory Pillar Memorial: It was erected by the British in Perne village in the district for the soldiers killed in the Koregaon Bhima battle. -

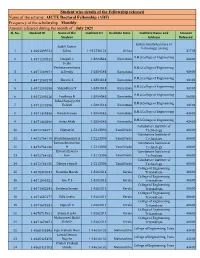

Student Wise Details of the Fellowship Released Name of the Scheme

Student wise details of the Fellowship released Name of the scheme: AICTE Doctoral Fellowship (ADF) Frequency of the scholarship –Monthly Amount released during the month of : July 2021 Sl. No. Student ID Name of the Institute ID Institute State Institute Name and Amount Student Address Released Indira Gandhi Institute of Sushil Kumar Technology, Sarang 1 1-4064399722 Sahoo 1-412736121 Orissa 31703 B.M.S.College of Engineering 2 1-4071237529 Deepak C 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Perla Venkatasreenivasu B.M.S.College of Engineering 3 1-4071249071 la Reddy 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 4 1-4071249170 Shruthi S 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 5 1-4071249196 Vidyadhara V 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 6 1-4071249216 Pruthvija B 1-5884543 Karnataka 86800 Tulasi Naga Jyothi B.M.S.College of Engineering 7 1-4071249296 Kolanti 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 8 1-4071448346 Manali Raman 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 9 1-4071448396 Anisa Aftab 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Coimbatore Institute of 10 1-4072764071 Vijayan M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 11 1-4072764119 Sivasubramani P A 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Ramasubramanian Coimbatore Institute of 12 1-4072764136 M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Eswara Eswara Coimbatore Institute of 13 1-4072764153 Rao 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 14 1-4072764158 Dhivya Priya N 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 -

Muslim Personal Law in India a Select Bibliography 1949-74

MUSLIM PERSONAL LAW IN INDIA A SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY 1949-74 SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Master of Library Science, 1973-74 DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIEVCE, ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH. Ishrat All QureshI ROLL No. 5 ENROLMENT No. C 2282 20 OCT 1987 DS1018 IMH- ti ^' mux^ ^mCTSSDmSi MUSLIM PERSONAL LAW IN INDIA -19I4.9 « i97l<. A SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIRSMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DESIEE OF MASTER .OF LIBRARY SCIENCE, 1973-7^ DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIENCE, ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH ,^.SHRAT ALI QURESHI Roll No.5 Enrolment Nb.C 2282 «*Z know tbt QUaa of Itlui elaiJi fliullty for tho popular sohools of Mohunodan Lav though thoj noror found it potslbla to dany the thaorotloal peasl^Ultj of a eoqplota Ijtlhad. Z hava triad to azplain tha oauaaa ¥hieh,in my opinion, dataminad tbia attitudo of tlia laaaaibut ainca thinga hcra ehangad and tha world of Ulan is today oonfrontad and affaetad bj nav foroaa sat fraa by tha extraordinary davalopaant of huaan thought in all ita diraetiona, I see no reason why thia attitude should be •aintainad any longer* Did tha foundera of our sehools ever elala finality for their reaaoninga and interpreti^ tionaT Navar* The elaii of tha pxasaat generation of Muslia liberala to raintexprat the foundational legal prineipleay in the light of their ovn ej^arla^oe and the altered eonditlona of aodarn lifs is,in wj opinion, perfectly Justified* Xhe teaehing of the Quran that life is a proeasa of progressiva eraation naeaaaltatas that eaoh generation, guided b&t unhampered by the vork of its predeoessors,should be peraittad to solve its own pxbbleas." ZQ BA L '*W« cannot n»gl«ct or ignoi* th« stupandoits vox^ dont by the aarly jurists but «• cannot b« bound by it; v« must go back to tha original sources 9 th« (^ran and tba Sunna. -

Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of Higher Education

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 2276 TO BE ANSWERED ON 02.12.2019 Universities 2276. SHRI COSME FRANCISCO CAITANO SARDINHA: Will the Minister of HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT be pleased to state: (a) whether any University in our country figures in the list of good universities listed by the international agencies; (b) if so, the details thereof; and (c) if not, the reasons therefor? ANSWER MINISTER OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT (SHRI RAMESH POKHRIYAL ‘NISHANK’) (a) & (b): Yes, Sir. As per Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings-2020 and Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) World University Ranking-2020, 36 and 24 Indian Universities / Institutions respectively figure in the top 1000 World University Rankings. The details of these Institutions / Universities are at Annexure-I. (c): In view of the above, does not arise. Annexure-I ANNEXURE REFERRED IN REPLY TO PART (a) AND (b) OF LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 2276 TO BE ANSWERED ON 02.12.2019 ASKED BY HONBLE MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT SHRI COSME FRANCISCO CAITANO SARDINHA REGARDING UNIVERSITIES List of Institutions / Universities found placed in top 1000 of world reputed ranking Agencies Agency THE World University Ranking QS World University Ranking-2020 Sl No. 2020 (Position) (Position) i. IISc, Bangalore – 301-350 IIT, Bombay - 152 ii. IIT, Ropar – 301-350 IIT, Delhi – 182 iii. IIT, Indore – 351-400 IISc, Bangalore - 184 iv. IIT, Bombay – 401-500 IIT, Madras – 271 v. IIT, Delhi - 401-500 IIT, Kharagpur – 281 vi. IIT, Kharagpur – 401-500 IIT, Kanpur - 291 vii. Institute of Chemical Technology, IIT, Roorkee – 383 Mumabi – 501-600 viii. -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

Dalit Theology and Indian Christian History in Dialogue: Constructive and Practical Possibilities

religions Article Dalit Theology and Indian Christian History in Dialogue: Constructive and Practical Possibilities Andrew Ronnevik Department of Religion, Baylor University, Waco, TX 76706, USA; [email protected] Abstract: In this article, I consider how an integration of Dalit theology and Indian Christian history could help Dalit theologians in their efforts to connect more deeply with the lived realities of today’s Dalit Christians. Drawing from the foundational work of such scholars as James Massey and John C. B. Webster, I argue for and begin a deeper and more comprehensive Dalit reading and theological analysis of the history of Christianity and mission in India. My explorations—touching on India’s Thomas/Syrian, Catholic, Protestant, and Pentecostal traditions—reveal the persistence and complexity of caste oppression throughout Christian history in India, and they simultaneously draw attention to over-looked, empowering, and liberative resources that are bound to Dalit Christians lives, both past and present. More broadly, I suggest that historians and theologians in a variety of contexts—not just in India—can benefit from blurring the lines between their disciplines. Keywords: Dalit theology; history of Indian Christianity; caste; liberation 1. Introduction In the early 1980s, Christian scholars in India began to articulate a new form of Citation: Ronnevik, Andrew. 2021. theology, one tethered to the lives of a particular group of Indian people. Related to libera- Dalit Theology and Indian Christian tion theology, postcolonialism, and Subaltern Studies, Dalit theology concentrates on the History in Dialogue: Constructive voices, experiences, and aspirations of India’s so-called “untouchables”, who constitute the and Practical Possibilities. -

Ethnographic Series, Sidhi, Part IV-B, No-1, Vol-V

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUMEV, PART IV-B, No.1 ETHNOGRAPHIC SERIES GUJARAT Preliminary R. M. V ANKANI, investigation Tabulation Officer, and draft: Office of the CensuS Superintendent, Gujarat. SID I Supplementary V. A. DHAGIA, A NEGROID L IBE investigation: Tabulation Officer, Office of the Census Superintendent, OF GU ARAT Gujarat. M. L. SAH, Jr. Investigator, Office of the Registrar General, India. Fieta guidance, N. G. NAG, supervision and Research Officer, revised draft: Office of the Registrar General, India. Editors: R. K. TRIVEDI, Su perintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. B. K. Roy BURMAN, Officer on Special Duty, (Handicrafts and Social Studies), Office of the Registrar General, India. K. F. PATEL, R. K. TRIVEDI Deputy Superintendent of Census Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. Operations, Gujarat N. G. NAG, Research Officer, Office' of the Registrar General, India. CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: '" I-A(i) General Report '" I-A(ii)a " '" I-A(ii)b " '" I-A(iii) General Report-Economic Trends and Projections :« I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey :I' I-C Subsidiary Tables '" II-A General Population Tables '" II-B(I) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) '" II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) '" II-C Cultural and Migration Tables :t< III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) "'IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments :t<IV-B Housing and Establishment -

INDIA Shadow Report

INDIA Shadow Report To the Third and Fourth Combined Report on the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child Submitted by CRC 20 BS Collective July 2012 Published by HAQ: Centre for Child Rights July 2011 Report by: CRC 20 BS collective C/O HAQ: Centre for Child Rights B1/2 Malviya Nagar New Delhi -110017 India Telephone: 91-11-26677412 Fax: 91-11- 26674688 Email: [email protected] Website: www.haqcrc.org Supported by: terre des hommes Germany 1 Preface Government of India submitted its Third and Fourth Combined Report on the Convention on the Rights of the Child to the Committee on the Rights of the Child in 2011, which the Committee is scheduled to consider in its 66th pre-sessional working group to be held in Geneva from 7-11 October 2013. This report by the CRC20BS (Balance Sheet) Collective, is being submitted as an alternative to that submitted by the Government. The CRC 20 BS collective (consisting of 173 organizations and 215 children associated with them) came together to undertake a review of the two decades of implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. It came out with a three volume report titled Twenty Years of CRC- A Balance Sheet in 2011. The process of pulling together the Balance Sheet through consultations with NGOs and children was undertaken by HAQ: Centre for Child Rights Delhi, supported by terre des hommes, Germany. The present shadow report is an update of the Balance Sheet of 2011 (already sent to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child). -

Re-Casting Food: Ethnographic Enquiry Into the Pre-School Supplementary Nutrition Programme, Gujarat, India

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 1–16 February 2020 brandeis.edu/j-caste ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v1i1.6 Re-Casting Food: Ethnographic Enquiry into the Pre-school Supplementary Nutrition Programme, Gujarat, India Nakkeeran N.1, Jadhav S.2, 1Bhattacharya A.3, Gamit S.1, Mehta C.1, Purohit P.1, Patel R.1 and Doshi M.12 Abstract This study is an ethnographic enquiry into the pre-school Supplementary Nutrition Programme (SNP), in India’s western Gujarat state. The broad objective was aimed at understanding the institutional barriers and sociological process that had led to the exclusion of families and children under the age of six from the SNP. This study was undertaken because despite enthusiastic State investment in human resources and food funding, the uptake of SNP was poor. The study method involved multi-sited ethnographies conducted in four rural villages of Gujarat. The research concluded that caste and religious identities shaped dominance and control, restriction of social interactions, and food commensality. The authors situate these compelling findings within the broader discourse of food as a process of ‘othering,’ and stigmatised identities as they relate to consumption of ‘polluting’ food, the symbolic role of food when coupled with caste, and association of religion with food. Observations of SNP delivery sites suggest that spatial and moral dimension of societal caste conflicts directly influence local ‘biologies’ by reproducing and amplifying such tensions in the Anganwadi1 health centres. Crucial symbolic and cultural markers of food, nutrition, distribution, and consumption are rendered invisible to official health providers resulting in failure of the SNP programme. -

Understanding the Contribution of Satya Shodhaak Samaj and Neo- Buddhism for Social Awakening

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347–4564; ISSN (E): 2321–8878 Vol. 8, Issue 6, Jun 2020, 53–60 © Impact Journals UNDERSTANDING THE CONTRIBUTION OF SATYA SHODHAAK SAMAJ AND NEO- BUDDHISM FOR SOCIAL AWAKENING Prashant V. Ransure & Pankajkumar Shankar Premsagar Assistant Professor, Department of History, Maratha Vidya Prasarak Samaj's Arts Science and Commerce College Ozar MIG, Maharashtra, India Associate Professor, Department of History, Smt. G. G. Khadse College, Muktainagar, India Received: 10 Jun 2020 Accepted: 16 Jun 2020 Published: 27 Jun 2020 ABSTRACT Indian Civilization is the conglomeration of various ethnic traditions; Years of amalgamation and change have led Indian civilization to have, diversity of culture religion, language, and caste groups. Indian Civilization is the conglomeration of various ethnic traditions; Years of amalgamation and change have led Indian civilization to have diversity of culture religion, language, and caste groups.1 The social reform movements, tried for the emancipation of these low caste people, before coming of these social reformers, many of the low caste people had chosen to come out from the caste system is by getting religious conversion, getting converted either to Christianity or to Islam, prior to these social reformers the saints like Kabir, Ravidas, Namdev, like wise and many other fought for the abolition of the caste system and emancipate the low caste from the social bondages.2 The other way for the untouchables was to get converted to either Islam or to Christianity, this was to get rid of the bondages of the humiliations of the caste system, but the conversion was not confined to the weaker sections, but in the medieval period too many people got converted to Islam or Christianity either by force or by their will. -

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination by Purvi Mehta A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Chair Professor Pamela Ballinger Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Matthew Hull Professor Mrinalini Sinha Dedication For my sister, Prapti Mehta ii Acknowledgements I thank the dalit activists that generously shared their work with me. These activists – including those at the National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights, Navsarjan Trust, and the National Federation of Dalit Women – gave time and energy to support me and my research in India. Thank you. The research for this dissertation was conducting with funding from Rackham Graduate School, the Eisenberg Center for Historical Studies, the Institute for Research on Women and Gender, the Center for Comparative and International Studies, and the Nonprofit and Public Management Center. I thank these institutions for their support. I thank my dissertation committee at the University of Michigan for their years of guidance. My adviser, Farina Mir, supported every step of the process leading up to and including this dissertation. I thank her for her years of dedication and mentorship. Pamela Ballinger, David Cohen, Fernando Coronil, Matthew Hull, and Mrinalini Sinha posed challenging questions, offered analytical and conceptual clarity, and encouraged me to find my voice. I thank them for their intellectual generosity and commitment to me and my project. Diana Denney, Kathleen King, and Lorna Altstetter helped me navigate through graduate training.