Biodiversity Conservation and Rural Livelihood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between the Hanns Seidel Foundation Pakistan and the Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad Islamabad, 2020 Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Edited by Sarah Holz Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office and Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan Acknowledgements Thank you to Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office for the generous and continued support for empirical research in Pakistan, in particular: Kristóf Duwaerts, Omer Ali, Sumaira Ihsan, Aisha Farzana and Ahsen Masood. This volume would not have been possible without the hard work and dedication of a large number of people. Sara Gurchani, who worked as the research assistant of the collaboration in 2018 and 2019, provided invaluable administrative, organisational and editorial support for this endeavour. A big thank you the HSF grant holders of 2018 who were not only doing their own work but who were also actively engaged in the organisation of the international workshop and the lecture series: Ibrahim Ahmed, Fateh Ali, Babar Rahman and in particular Adil Pasha and Mohsinullah. Thank you to all the support staff who were working behind the scenes to ensure a smooth functioning of all events. A special thanks goes to Shafaq Shafique and Muhammad Latif sahib who handled most of the coordination. Thank you, Usman Shah for the copy editing. The research collaboration would not be possible without the work of the QAU faculty members in the year 2018, Dr. Saadia Abid, Dr. -

Economic and Revenue Sector for the Year Ended 31 March 2019

Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Economic and Revenue Sector for the year ended 31 March 2019 GOVERNMENT OF GUJARAT (Report No. 3 of the year 2020) http://www.cag.gov.in TABLE OF CONTENTS Particulars Paragraph Page Preface vii Overview ix - xvi PART – I Economic Sector CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION About this Report 1.1 1 Audited Entity Profile 1.2 1-2 Authority for Audit 1.3 3 Organisational structure of the Office of the 1.4 3 Principal Accountant General (Audit-II), Gujarat Planning and conduct of Audit 1.5 3-4 Significant audit observations 1.6 4-8 Response of the Government to Audit 1.7 8-9 CHAPTER II – COMPLIANCE AUDIT AGRICULTURE, FARMERS WELFARE AND CO-OPERATION DEPARTMENT Functioning of Junagadh Agricultural University 2.1 11-32 INDUSTRIES AND MINES DEPARTMENT Implementation of welfare programme for salt 2.2 32-54 workers FORESTS AND ENVIRONMENT DEPARTMENT Compensatory Afforestation 2.3 54-75 PART – II Revenue Sector CHAPTER–III: GENERAL Trend of revenue receipts 3.1 77 Analysis of arrears of revenue 3.2 80 i Arrears in assessments 3.3 81 Evasion of tax detected by the Department 3.4 81 Pendency of Refund Cases 3.5 82 Response of the Government / Departments 3.6 83 towards audit Audit Planning and Results of Audit 3.7 86 Coverage of this Report 3.8 86 CHAPTER–IV: GOODS AND SERVICES TAX/VALUE ADDED TAX/ SALES TAX Tax administration 4.1 87 Results of Audit 4.2 87 Audit of “Registration under GST” 4.3 88 Non/short levy of VAT due to misclassification 4.4 95 /application of incorrect rate of tax Irregularities -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads - A Literature Review Anita Sharma CREATE PATHWAYS TO ACCESS Research Monograph No. 58 January 2011 University of Sussex Centre for International Education The Consortium for Educational Access, Transitions and Equity (CREATE) is a Research Programme Consortium supported by the UK Department for International Development (DFID). Its purpose is to undertake research designed to improve access to basic education in developing countries. It seeks to achieve this through generating new knowledge and encouraging its application through effective communication and dissemination to national and international development agencies, national governments, education and development professionals, non-government organisations and other interested stakeholders. Access to basic education lies at the heart of development. Lack of educational access, and securely acquired knowledge and skill, is both a part of the definition of poverty, and a means for its diminution. Sustained access to meaningful learning that has value is critical to long term improvements in productivity, the reduction of inter- generational cycles of poverty, demographic transition, preventive health care, the empowerment of women, and reductions in inequality. The CREATE partners CREATE is developing its research collaboratively with partners in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The lead partner of CREATE is the Centre for International Education at the University of Sussex. The partners are: -

Annotated Bibliography of Studies on Muslims in India

Studies on Muslims in India An Annotated Bibliography With Focus on Muslims in Andhra Pradesh (Volume: ) EMPLOYMENT AND RESERVATIONS FOR MUSLIMS By Dr.P.H.MOHAMMAD AND Dr. S. LAXMAN RAO Supervised by Dr.Masood Ali Khan and Dr.Mazher Hussain CONFEDERATION OF VOLUNTARY ASSOCIATIONS (COVA) Hyderabad (A. P.), India 2003 Index Foreword Preface Introduction Employment Status of Muslims: All India Level 1. Mushirul Hasan (2003) In Search of Integration and Identity – Indian Muslims Since Independence. Economic and Political Weekly (Special Number) Volume XXXVIII, Nos. 45, 46 and 47, November, 1988. 2. Saxena, N.C., “Public Employment and Educational Backwardness Among Muslims in India”, Man and Development, December 1983 (Vol. V, No 4). 3. “Employment: Statistics of Muslims under Central Government, 1981,” Muslim India, January, 1986 (Source: Gopal Singh Panel Report on Minorities, Vol. II). 4. “Government of India: Statistics Relating to Senior Officers up to Joint-Secretary Level,” Muslim India, November, 1992. 5. “Muslim Judges of High Courts (As on 01.01.1992),” Muslim India, July 1992. 6. “Government Scheme of Pre-Examination Coaching for Candidates for Various Examination/Courses,” Muslim India, February 1992. 7. National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO), Department of Statistics, Government of India, Employment and Unemployment Situation Among Religious Groups in India: 1993-94 (Fifth Quinquennial Survey, NSS 50th Round, July 1993-June 1994), Report No: 438, June 1998. 8. Employment and Unemployment Situation among Religious Groups in India 1999-2000. NSS 55th Round (July 1999-June 2000) Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, September 2001. Employment Status of Muslims in Andhra Pradesh 9. -

Using Participatory Action Research Methodologies for Engaging and Researching with Religious Minorities in Contexts of Intersecting Inequalities

CREID WORKING PAPER Volume 2021 · Number 05 · January 2021 Using Participatory Action Research Methodologies for Engaging and Researching with Religious Minorities in Contexts of Intersecting Inequalities Sowmyaa Bharadwaj, Jo Howard and Pradeep Narayan About CREID The Coalition for Religious Equality and Inclusive Development (CREID) provides research evidence and delivers practical programmes which aim to redress poverty, hardship, and exclusion resulting from discrimination on the grounds of religion or belief. CREID is an international consortium led by the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) and funded by UK aid from the UK Government (Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office – FCDO). Key partners include Al-Khoei Foundation, Minority Rights Group (MRG), and Refcemi. Find out more: www.ids.ac.uk/creid. © Institute of Development Studies 2021 ISBN: 978-1-78118-733-3 DOI: 10.19088/CREID.2020.009 This is an Open Access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated. Available from: Coalition for Religious Equality and Inclusive Development (CREID), Institute of Development Studies (IDS), Brighton BN1 9RE, UK Tel: +44(0) 1273 915704 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ids.ac.uk/creid IDS is a charitable company limited by guarantee and registered in England Charity Registration Number 306371 Charitable Company Number 877338 1 Using Participatory Action Research Methodologies for Engaging and Researching with Religious Minorities in Contexts of Intersecting Inequalities Sowmyaa Bharadwaj, Jo Howard and Pradeep Narayanan Summary While there is growing scholarship on the intersectional nature of people’s experience of marginalisation, analyses tend to ignore religion-based inequalities. -

Missionary Biography, Mobin Khan

Editorial October 2018 SUBSCRIPTIONS Frontier Ventures-GPD, PO Box 91297 Long Beach, CA 90809, USA 1-888-881-5861 or 1-714-226-9782 for Canada and overseas PRAY FOR Dear Praying Friends, [email protected] The last two years I have attended the Finishing the Task EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Keith Carey Every Unreached, Unengaged (FTT) conference here in Southern California. The purpose For comments on content call of this conference in simple terms is to get believers to 626-398-2241 or email [email protected] Muslim Group in India adopt (commit) to plant churches among the remaining ASSISTANT EDITOR people groups that lack a missionary presence. We call these Paula Fern “unengaged” unreached people groups. FTT produces lists WRITERS of these unreached, unengaged peoples (UUPGs), that are Eugena Chou changing as groups of believers adopt them. In fact, the list Patricia Depew Karen Hightower we used for this prayer guide changed right after I assigned Wesley Kawato stories to the writers! This month we will be praying for David Kugel Christopher Lane Muslim UUPGs in India. Ted Proffitt Cory Raynham Did you know you now can get FREE GPD materials? You Lydia Reynolds Jean Smith can still get the printed versions of our Global Prayer Digest, Allan Starling Chun Mei Wilson but we have a free app, that you can get by going to the John Ytreus Google Play Store and searching for “Global Prayer Digest.” DAILY BIBLE COMMENTARIES You can also get daily prayer materials in your inbox by Keith Carey going to our website and entering your email address in the CUSTOMER SERVICE box in the upper right corner. -

The Musalman Races Found in Sindh

A SHORT SKETCH, HISTORICAL AND TRADITIONAL, OF THE MUSALMAN RACES FOUND IN SINDH, BALUCHISTAN AND AFGHANISTAN, THEIR GENEALOGICAL SUB-DIVISIONS AND SEPTS, TOGETHER WITH AN ETHNOLOGICAL AND ETHNOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT, BY SHEIKH SADIK ALÍ SHER ALÍ, ANSÀRI, DEPUTY COLLECTOR IN SINDH. PRINTED AT THE COMMISSIONER’S PRESS. 1901. Reproduced By SANI HUSSAIN PANHWAR September 2010; The Musalman Races; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 DEDICATION. To ROBERT GILES, Esquire, MA., OLE., Commissioner in Sindh, This Volume is dedicated, As a humble token of the most sincere feelings of esteem for his private worth and public services, And his most kind and liberal treatment OF THE MUSALMAN LANDHOLDERS IN THE PROVINCE OF SINDH, ВY HIS OLD SUBORDINATE, THE COMPILER. The Musalman Races; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 PREFACE. In 1889, while I was Deputy Collector in the Frontier District of Upper Sindh, I was desired by B. Giles, Esquire, then Deputy Commissioner of that district, to prepare a Note on the Baloch and Birahoi tribes, showing their tribal connections and the feuds existing between their various branches, and other details. Accordingly, I prepared a Note on these two tribes and submitted it to him in May 1890. The Note was revised by me at the direction of C. E. S. Steele, Esquire, when he became Deputy Commissioner of the above district, and a copy of it was furnished to him. It was revised a third time in August 1895, and a copy was submitted to H. C. Mules, Esquire, after he took charge of the district, and at my request the revised Note was printed at the Commissioner-in-Sindh’s Press in 1896, and copies of it were supplied to all the District and Divisional officers. -

Village Survey Monograph, Sutrapada Fishing Hamlet, Part VI, No-9, Vol-V

PH.G. 27 (N) 1,000 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME V-PART VI-NO.9 GUJARAT VILLAGE SURVEY MONOGRAPH 9. SUTRAPADA FISHING IIAl\lLET DISTRICT : J UNAGADH TALUKA : PATAN VERAVAL R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations:J Gujarat PRICE Rs. 3.10 or 7 Sh. 3 d. or $ U.S. 1.12 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: * I-A(i) General Report :I< I-A(ii)a * I-A(ii)b " :I< I-A(iii) General Report-Economic Trends and Projections '" I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey "" I-C Subsidiary Tables ... II-A General Population Tables * II-B(l) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) :I< II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) '" II-C Cultural and Migration Tables -;\< III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) * IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments *IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables '" V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) >\<>\< VI Village Survey MonOgraphs t VII-A Selected Crafts of Gujarat "" VII-B Fairs and Festivals >\< VIII-A Administration R~ort-Enumeration Not for Sale :l<VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation J >I< IX Atlas Volume "" X-A(i) Special Report on Ahmedabad City X-A(ii) Special Report on Cities '" X-B Special Tables on Cities and Block Directory '" X-C Special Migrant Tables for Ahmedabad City STATE GOVERNMENT PuBLICATIONS * 1 7 District Census Hand books in English >\< 1 7 District Census Handbooks in Gujarati * Published ** Village Survey Monographs for seven villages, Pachhatardi, Magdalla, Bhirandiara, Bamanbore, Tavadia, Isanpur and Ghadvi published :j: Monographs on Agate Industry of Cambay, Wood-carving of Gujarat, Patara Making at Bhavnagar, Ivory work of Mahuva, Padlock Making at Sarva, Scale Making -of Savarkundla, Perfumery at Palanpur and Crochet work of J amnagar published PRINTED BY JIVANJI D. -

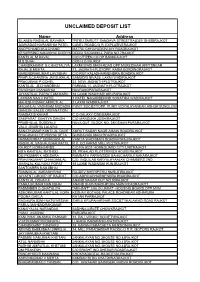

Unclaimed Deposit List

UNCLAIMED DEPOSIT LIST Name Address SILABEN RASIKLAL BAVARIA "PITRU SMRUTI" SANGAVA STREETRAJDEV SHERIRAJKOT JAMNADAS NARANBHAI PATEL CANEL ROADC/O R. EXPLASIVERAJKOT ANOPCHAND MULCHAND MATRU CHHAYADIGVIJAY ROADRAJKOT KESARISING NANJIBHAI DODIYA DODIA SADANMILL PARA NO.7RAJKOT KANTILAL M RAVAL C/O CITIZEN CO.OP.BANKRAJKOT M S SHAH CCB.H.O.RAJKOT CHANDRAKANT G CHHOTALIYA LAXMI WADI MAIN ROAD OPP MURLIDHAR APPTSNEAR RAJAL B MEHTA 13, JAGNATH PLOTOPP. KADIA BORDINGRAJKOT NARENDRAKUMAR LAVJIBHAI C/O RUP KALADHARMENDRA ROADRAJKOT PRAFULCHANDRA JAYSUKHLAL SAMUDRI NIVAS5, LAXMI WADIRAJKOT PRAGJIBHAI P GOHEL 22. NEW JAGNATH PLOTRAJKOT KANTILAL JECHANDBHAI PARIMAL11, JAGNATH PLOTRAJKOT RAYDHAN CHANABHAI NAVRANGPARARAJKOT JAYANTILAL PARSOTAM MARU 18 LAXMI WADIHARI KRUPARAJKOT LAXMAN NAGJI PATEL 1 PATEL NAGARBEHIND SORATHIA WADIRAJKOT MAHESHKUMAR AMRUTLAL 2 LAXMI WADIRAJKOT MAGANLAL VASHRAM MODASIA PUNIT SOCIETYOPP. PUNIT VIDYALAYANEAR ASHOK BUNGLOW GANESH SALES ORGANATION RAMDAS B KAHAR C.O GALAXY CINEMARAJKOT SAMPARAT SAHITYA SANGH C/O MANSUKH JOSHIRAJKOT PRABHULAL BUDDHAJI NAVA QUT. BLOCK NO. 28KISHAN PARARAJKOT VALJI JIVABHIA LALKIYA SANATKUMAR KANTILAL DAVE AMRUT SADAR NAGR AMAIN ROADRAJKOT BHAGWANJI DEVSIBHAI SETA GUNDAVADI MAIN ROADRAJKOT HASMUKHRAY CHHAGANLAL VANIYA WADI MAIN ROADNATRAJRAJKOT RASIKLAL VAGHAJIBHAI PATEL R.K. CO.KAPAD MILL PLOTRAJKOT RAJKOT HOMEGARDS C/O RAJKOT HOMEGUARD CITY UNITRAJKOT NITA KANTILAL RATHOD 29, PRHALAD PLOTTRIVEDI HOUSERAJKOT DILIPKUMAR K ADESARA RAMNATH PARAINSIDE BAHUCHARAJI NAKARAJKOT PRAVINKUMAR CHHAGANLAL -

Village Survey Monograph, Village Magdalla, Part VI, No-2, Vol-V

PRG.21 (N) 1,000 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME V-PART VI-NO.2 GUJARAT VILLAGE SURVEY MONOGRAPH DISTRICT : SURAT TAL UKA : CHORASI VILLAGE MAG DALLA R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat :PRICE Ea. +.85 :p. or II Sh, 'I: Q. or fill U.S. l.75 VILLAGE SURVEY MAP OF MAGDALLA o 3/16 3/6 TALUKA : CHORASI DISTRICT: SURAT N GUJARAT H §5URAT + LEGEN 0 POND BROOK RIVER CANAL ROAD CART TRACK o WELL A TEMPLE ft TALUKA CJ VILLAGE SITE ITJIIIJ CULTIVATED r::=::=l ~ GRAl.ING LANe "(" A B H A v A PHOTOGRAPHS K. D. VAISHNAV Photographer MAPS I. F. DAVE Draftsman ART WORK SOMALAL SHAH Artist CHARTS U. K. SHAIKH FIELD INVESTIGATION A. P. SHAH Statistical Assistant, Block Development Office, NAVSARI R. p. DESHMUKH Statistical Assistant, Block Development Office, SONGADH SUPERVISION OF SURVEY T. K. TRIVEDI District Statistical Officer, SURAT FIRST DRAFT K. P. YAJNIK Depury Superintendent if Census Operations, (Special Studies Section), Gujarat, AHMEDABAD EDITOR R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat, AHMEDABAD UST OF VILLAGE SURVEY MONOGRAPHS TO BE PUBLISHED IN GUJARAT STATE S1. No. District Taluka/Mahal Village Reasons for selection 2 3 4 5 1 Jamnagar Bhanvad "'1 Pachhatardi Represents mixed economy of agriculture and animal husbandry. Okhamandal 2 Kuranga Study of sea-faring community of Waghers well known as sailors' and fishermen. 2 Rajkot Dhoraji 3 Chinchod Represents fertile agricultural area growing cotton and groundnut. Maliya 4 Kajarda Study of socio-economic condition of excriminal tribe of Miyana. 3 Surendranagar Chotila 5 Bamanbore Represents hilly Panchal area where cattle breeding predominates agriculture. -

Research Process Rabaris of Kutch-History Through Legends

50 Bina Sengar Research Process 2(1) January –June 2014, pp. 50-61 © Social Research Foundation Rabaris of Kutch-History Through Legends Bina Sengar Assistant Professor, Department of History and AIC Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, Aurangabad-431004 Email: [email protected] The research paper is an ethnographic study of the Rabari community of Kutch. The available studies on Rabaris are based on narratives’ of life and history of Rabaris through the anthropological surveys conducted during the British colonial times. The following study is based on the field works conducted in the region of Kutch and thereafter through the primary and secondary versions of the folk memories of the Rabari community which remains the significant identity of the Rann and its regions in Kutch. [Key Words: Jath, Kutch, Legend, Rabari, Rann] Kutch presents an epitome of the larger story of India constant invasions; a fusion of cultures; a dawning sense of nationalism, Kutchi annals are full of dramatic episodes; there is a remarkable wealth of ‘remembered history’ little of which has been written down” -William Rushbrook (1984:1) Kutch: The Land of Legends If one would go beyond history in the realm of a legend, several facets of cultural and their practices come to our knowledge. The value of these legends becomes more and more of importance when there is a paucity of any other written form of knowledge and sources to substantiate. The history of the common people very often lacks bardic literature or chronicles to represent their presence in past. Therefore, to traces their past value of their folk traditions becomes an invaluable source to study their past.