Research Process Rabaris of Kutch-History Through Legends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application No First Name Last Name Dob Domicile

ONLINE DOMICILE_ HSE_PE ONLINE HSE_50 GEND _ASS_5 MERIT_ APPLICATION_NO FIRST_NAME LAST_NAME DOB DISTRICT_ CASTE RCENTA _ASS_S _WEIGH ER 0_WEIG MARKS NAME GE CORE TAGE HTAGE 030412054771 AMIT TRIPATHI 31/07/1979 Jabalpur UR M 78.22 83 39.11 41.5 80.61 030412090866 NEERAJ KURARIYA 10/11/1988 Jabalpur UR M 84.22 76 42.11 38 80.11 030412050851 AMIT KURARIA 18/07/1979 Jabalpur UR M 73.78 85 36.89 42.5 79.39 030412033902 NITESH YADAV 20/04/1990 Jabalpur OBC M 75.78 79 37.89 39.5 77.39 030412003591 PIYUSH KANT VISHWAKARMA 17/06/1987 Jabalpur OBC M 85.11 67 42.56 33.5 76.06 030412017892 SHALINI SONI 21/07/1989 Jabalpur OBC F 79.78 72 39.89 36 75.89 030412067488 RUCHI KOSHTA 25/05/1988 Jabalpur OBC F 87.78 62 43.89 31 74.89 030412004013 PRABHAT PAROHA 01/08/1987 Jabalpur UR M 83.33 66 41.67 33 74.67 030412042225 SUDHANSU KUMAR 17/06/1989 Jabalpur UR M 77.11 72 38.56 36 74.56 030412077856 AARTI AGRAWAL 21/10/1989 Jabalpur UR F 90.67 58 45.34 29 74.34 030412074769 AJEET SINGH RAGHUWANSHI 01/07/1989 Jabalpur UR M 82.67 65 41.34 32.5 73.84 030412104573 POOJA AHUJA 09/05/1988 Jabalpur UR F 80.67 66 40.34 33 73.34 030412060585 UPENDRA MISHRA 10/03/1987 Jabalpur UR M 78.44 68 39.22 34 73.22 030412073393 ASHUTOSH MOGHE 28/10/1979 Jabalpur UR M 78.22 68 39.11 34 73.11 030412060496 SWATI AGRAHARI 06/08/1989 Jabalpur UR F 86 60 43 30 73 030412064398 MANISH KUMAR RAI 20/10/1986 Jabalpur OBC M 78.89 67 39.45 33.5 72.95 030412082906 ASHISH KUMAR JAIN 12/03/1986 Jabalpur UR M 86.67 59 43.34 29.5 72.84 030412084151 RATAN CHAKRAWARTI 28/04/1988 Jabalpur OBC M -

Steppe Nomads in the Eurasian Trade1

Volumen 51, N° 1, 2019. Páginas 85-93 Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena STEPPE NOMADS IN THE EURASIAN TRADE1 NÓMADAS DE LA ESTEPA EN EL COMERCIO EURASIÁTICO Anatoly M. Khazanov2 The nomads of the Eurasian steppes, semi-deserts, and deserts played an important and multifarious role in regional, interregional transit, and long-distance trade across Eurasia. In ancient and medieval times their role far exceeded their number and economic potential. The specialized and non-autarchic character of their economy, provoked that the nomads always experienced a need for external agricultural and handicraft products. Besides, successful nomadic states and polities created demand for the international trade in high value foreign goods, and even provided supplies, especially silk, for this trade. Because of undeveloped social division of labor, however, there were no professional traders in any nomadic society. Thus, specialized foreign traders enjoyed a high prestige amongst them. It is, finally, argued that the real importance of the overland Silk Road, that currently has become a quite popular historical adventure, has been greatly exaggerated. Key words: Steppe nomads, Eurasian trade, the Silk Road, caravans. Los nómadas de las estepas, semidesiertos y desiertos euroasiáticos desempeñaron un papel importante y múltiple en el tránsito regional e interregional y en el comercio de larga distancia en Eurasia. En tiempos antiguos y medievales, su papel superó con creces su número de habitantes y su potencial económico. El carácter especializado y no autárquico de su economía provocó que los nómadas siempre experimentaran la necesidad de contar con productos externos agrícolas y artesanales. Además, exitosos Estados y comunidades nómadas crearon una demanda por el comercio internacional de bienes exóticos de alto valor, e incluso proporcionaron suministros, especialmente seda, para este comercio. -

List of Approved Registered Graduates of Commerce Faculty 2017, Bhuj Taluka

LIST OF APPROVED REGISTERED GRADUATES OF COMMERCE FACULTY 2017, BHUJ TALUKA Sr. No. Name Address Taluka Reg No Challan No ACHARYA MALHAR DWIDHAMESHWAR BHUJ 992 1 PRAFULBHAI COLONY, BHUJ ACHARYA NANDISH 366/B BHUJ 798 BIMALKUMAR ,"NADIGRAM",ODHAV VILL RAW HOUSING, 2 AIYA NAGAR, MUNDRA ROAD,BHUJ,7567569745 ACHARYA RAHUL JUNI RAWALVADI P.L.- BHUJ 440 3 CHANDULAL 270,BHUJ, 814001211 AHALAPARA AT-149-152/2, ODHAV BHUJ 824 DULARI ASHOKBHAI EVENUE, MUNDRA 4 RELOCATION SITE,BHUJ AHALPARA DULARI 149, MUNDRA BHUJ 1055 5 ASHOKBHAI RELOCATION SITE, BHUJ. AHIR MOHINI 72, NRNARAYAN BHUJ 528 GOPALBHAI NAGAR, NR CHABUTRA CHOWK, GARBI CHOWK 6 JUNAVAS, MADHAPAR BHUJ, 9913838887 AHIR SHIVJI GOPAL 24, SHAKTI NAGAR-2, BHUJ 1099 BEHIND SORTHIYA 7 SAMAJWADI,JUNAVAS, MADHPAPAR, BHUJ, 9979980151 AJANI NAYAN SURAL BHIT ROAD, BHUJ 429 8 VASANTLAL MARKET YARD, BHUJ. 8140091211 AJANI VRAJNI JYUBELI HOSPITAL BHUJ 961 VASANTBHAI STREET-1, HATHISTHAN 9 SALA , BHUJ,8511312641 AKHANI POOJABEN 101, AIYA NAGAR, BHUJ 344 NIRANJANBHAI JUNA VAS, MADHAPAR, 10 TALUKA – BHUJ. 9725086947 AMRANI BHAKTI HOUSE NO:6, ANAND BHUJ 1402 KISHANCHAND BHAVAN, VRUNDAVAN PARK SOCIETY,OLD 11 RAILWAY STATION, BHUJ ANTANI CHIRAG 48/53-6, YOGIRAJ PARK BHUJ 580 SIRISHBHAI ,OPP ST WORKSHOP, 12 SANSKAR NAGAR,BHUJ, 9879292898 ANTANI HARASHAL 48-53/6, YOGIRAJ PARK, BHUJ 1343 SHIRISHBHAI OPP. ST WORKSHOP, 13 SANSKAR NAGAR, BHUJ ANTANI HARSHAL 48/53-6, YOGIRAJ PARK, BHUJ 425 SHIRISHBHAI OPPOSITE ST WORK SHOP, SANSKAR NAGAR, 14 BHUJ. 9638553439 9825337877 ANTANI JIGNEY KARISHMA, SANSKAR BHUJ 1200 15 BHASKARBHAI NAGAR 33/A, NEAR ST WORKSHOP, BHUJ. ARODA JITENDRA 331/3 B SANKAR BHUJ 1439 16 KHUSHALCHAND TRECTOR,JUNAVAS MADHAPAR,BHUJ ARUNKUMAR ASHAPURA TOWN SHIP, BHUJ 1559 17 JAGDISHPRASHAD AIRPORT ROAD, BHUJ, H. -

List of Entries

List of Entries A Ahmad Raza Khan Barelvi 9th Month of Lunar Calendar Aḥmadābād ‘Abd al-Qadir Bada’uni Ahmedabad ‘Abd’l-RaḥīmKhān-i-Khānān Aibak (Aybeg), Quṭb al-Dīn Abd al-Rahim Aibek Abdul Aleem Akbar Abdul Qadir Badauni Akbar I Abdur Rahim Akbar the Great Abdurrahim Al Hidaya Abū al-Faḍl ‘Alā’ al-Dīn Ḥusayn (Ghūrid) Abū al-Faḍl ‘Allāmī ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Khaljī Abū al-Faḍl al-Bayhaqī ʿAlāʾ al-DīnMuḥammad Shāh Khaljī Abū al-Faḍl ibn Mubarak ‘Alā’ ud-Dīn Ḥusain Abu al-Fath Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar ʿAlāʾ ud-Dīn Khiljī Abū al-KalāmAzād AlBeruni Abū al-Mughīth al-Ḥusayn ibn Manṣūr al-Ḥallāj Al-Beruni Abū Ḥafṣ ʿUmar al-Suhrawardī AlBiruni Abu’l Fazl Al-Biruni Abu’l Fazl ‘Allāmī Alfī Movements Abu’l Fazl ibn Mubarak al-Hojvīrī Abū’l Kalām Āzād Al-Huda International Abū’l-Fażl Bayhaqī Al-Huda International Institute of Islamic Educa- Abul Kalam tion for Women Abul Kalam Azad al-Hujwīrī Accusing Nafs (Nafs-e Lawwāma) ʿAlī Garshāsp Adaran Āl-i Sebüktegīn Afghan Claimants of Israelite Descent Āl-i Shansab Aga Khan Aliah Madrasah Aga Khan Development Network Aliah University Aga Khan Foundation Aligarh Muslim University Aga Khanis Aligarh Muslim University, AMU Agyaris Allama Ahl al-Malāmat Allama Inayatullah Khan Al-Mashriqi Aḥmad Khān Allama Mashraqi Ahmad Raza Khan Allama Mashraqui # Springer Science+Business Media B.V., part of Springer Nature 2018 827 Z. R. Kassam et al. (eds.), Islam, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism, Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1267-3 828 List of Entries Allama Mashriqi Bangladesh Jamaati-e-Islam Allama Shibili Nu’mani Baranī, Żiyāʾ al-Dīn Allāmah Naqqan Barelvīs Allamah Sir Muhammad Iqbal Barelwīs Almaniyya BāyazīdAnṣārī (Pīr-i Rōshan) Almsgiving Bāyezīd al-Qannawjī,Muḥammad Ṣiddīq Ḥasan Bayhaqī,Abūl-Fażl Altaf Hussain Hali Bāzīd Al-Tawḥīd Bedil Amīr ‘Alī Bene Israel Amīr Khusrau Benei Manasseh Amir Khusraw Bengal (Islam and Muslims) Anglo-Mohammedan Law Bhutto, Benazir ʿAqīqa Bhutto, Zulfikar Ali Arezu Bīdel Arkān al-I¯mān Bidil Arzu Bilgrāmī, Āzād Ārzū, Sirāj al-Dīn ‘Alī Ḳhān (d. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi Andhra in India Adi Dravida in India Population: 307,000 Population: 8,598,000 World Popl: 307,800 World Popl: 8,598,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other Main Language: Telugu Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.86% Chr Adherents: 0.09% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible Source: Anonymous www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Dr. Nagaraja Sharma / Shuttersto "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi Karnataka in India Agamudaiyan in India Population: 2,974,000 Population: 888,000 World Popl: 2,974,000 World Popl: 906,000 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Hindu - other Main Language: Kannada Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.51% Chr Adherents: 0.50% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous Source: Anonymous "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Agamudaiyan Nattaman -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between the Hanns Seidel Foundation Pakistan and the Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad Islamabad, 2020 Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Edited by Sarah Holz Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office and Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan Acknowledgements Thank you to Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office for the generous and continued support for empirical research in Pakistan, in particular: Kristóf Duwaerts, Omer Ali, Sumaira Ihsan, Aisha Farzana and Ahsen Masood. This volume would not have been possible without the hard work and dedication of a large number of people. Sara Gurchani, who worked as the research assistant of the collaboration in 2018 and 2019, provided invaluable administrative, organisational and editorial support for this endeavour. A big thank you the HSF grant holders of 2018 who were not only doing their own work but who were also actively engaged in the organisation of the international workshop and the lecture series: Ibrahim Ahmed, Fateh Ali, Babar Rahman and in particular Adil Pasha and Mohsinullah. Thank you to all the support staff who were working behind the scenes to ensure a smooth functioning of all events. A special thanks goes to Shafaq Shafique and Muhammad Latif sahib who handled most of the coordination. Thank you, Usman Shah for the copy editing. The research collaboration would not be possible without the work of the QAU faculty members in the year 2018, Dr. Saadia Abid, Dr. -

Án Zimonyi, Medieval Nomads in Eastern Europe

As promised, after the appearance of Crusaders, in Slavic or Balkan languages, or Russian authors Missionaries and Eurasian Nomads in the 13th who confine themselves to bibliography in their 14th Centuries: A Century of Interaction, Hautala own mother tongue,” Hautala’s linguistic capabili did indeed publish an anthology of annotated ties enabled him to become conversant with the Russian translations of the Latin texts.10 In his in entire field of Mongol studies (14), for which all troduction, Spinei observes that “unlike WestEu specialists in the Mongols, and indeed all me ropean authors who often ignore works published dievalists, should be grateful. 10 Ot “Davida, tsaria Indii” do “nenavistnogo plebsa satany”: Charles J. Halperin antologiia rannikh latinskikh svedenii o tataromongolakh (Kazan’: Mardzhani institut AN RT, 2018). ——— István Zimonyi. Medieval Nomads in Eastern Part I, “Volga Bulgars,” the subject of Zimonyi’s Europe: Collected Studies. Ed. Victor Spinei. Englishlanguage monograph,1 contains eight arti Bucureşti: Editoru Academiei Romăne, Brăila: cles. In “The First Mongol Raids against the Volga Editura Istros a Muzueului Brăilei, 2014. 298 Bulgars” (1523), Zimonyi confirms the report of pp. Abbreviations. ibnAthir that the Mongols, after defeating the his anthology by the distinguished Hungarian Kipchaks and the Rus’ in 1223, were themselves de Tscholar of the University of Szeged István Zi feated by the Volga Bolgars, whose triumph lasted monyi contains twentyeight articles, twentyseven only until 1236, when the Mongols crushed Volga of them previously published between 1985 and Bolgar resistance. 2013. Seventeen are in English, six in Russian, four In “Volga Bulgars between Wind and Water (1220 in German, and one in French, demonstrating his 1236)” (2533), Zimonyi explores the preconquest adherence to his own maxim that without transla period of BulgarMongol relations further. -

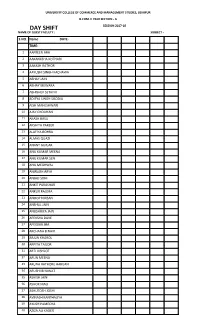

Day Shift Session 2017-18 Name of Guest Faculty : Subject - S.No

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. II YEAR SECTION - A DAY SHIFT SESSION 2017-18 NAME OF GUEST FACULTY : SUBJECT - S.NO. Name DATE- TIME- 1 AAFREEN ARA 2 AAKANKSHA KOTHARI 3 AAKASH RATHOR 4 AAYUSHI SINGH KACHAWA 5 ABHAY JAIN 6 ABHAY MEWARA 7 ABHISHEK SETHIYA 8 ADITYA SINGH SISODIA 9 AISH MAHESHWARI 10 AJAY CHOUHAN 11 AKASH BASU 12 AKSHITA PAREEK 13 ALAFIYA BOHRA 14 ALMAS QUAZI 15 ANANT GURJAR 16 ANIL KUMAR MEENA 17 ANIL KUMAR SEN 18 ANIL MEGHWAL 19 ANIRUDH ARYA 20 ANJALI SONI 21 ANKIT PARASHAR 22 ANKUR RAJORA 23 ANOOP NIRBAN 24 ANSHUL JAIN 25 ANUSHRIYA JAIN 26 APEKSHA DAVE 27 APEKSHA JHA 28 ARCHANA B NAIR 29 ARJUN KHAROL 30 ARPITA TAILOR 31 ARTI VISHLOT 32 ARUN MEENA 33 ARUNA RATHORE HARIJAN 34 ARUSHI BIYAWAT 35 ASHISH JAIN 36 ASHOK MALI 37 ASHUTOSH JOSHI 38 AVINASH KANTHALIYA 39 AYUSH PAMECHA 40 AZIZA ALI KADER 41 BATUL 42 BHARAT LOHAR 43 BHARAT MEENA 44 BHARAT PURI GOSWAMI 45 BHAVIN JAIN 46 BHAWANA SOLANKI 47 BHUMIKA JAIN 48 BHUMIKA PALIYA 49 BHUMIT SEVAK 50 BHUPENDRA JAIN 51 BINISH KHAN 52 BURHANUDDIN MOOMIN 53 CHANCHAL SOLANKI 54 CHETAN KOTIA 55 DAKSH VYAS 56 DANISH KHAN 57 DARSHIT DOSHI 58 DEEPAK NAGDA 59 DEEPAK SHRIMALI 60 DEEPIKA SAHU 61 DEEPIKA SINGH KHARWAR 62 DEEPIKA YADAV 63 DEEPTI KUMAWAT 64 DHRUVIT KUMAWAT 65 DIKSHANT VAIRAGI 66 DINESH KUMAR MEENA 67 DINESH NAGDA 68 DINESH RAJPUROHIT 69 DIPESH JAIN 70 DIVYA GUPTA 71 DIVYA JAIN 72 DIVYA MALI 73 DIVYA NAKWAL 74 DIVYA SONI 75 DURGA BHATT 76 DURGA SHANKAR MALI 77 FATEMA BOHRA 78 FIRDOSH MANSURI 79 GAJENDRA MENARIA 80 GAJENDRA PUSHKARNA Signature of Guest Faculty DEAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. -

Economic and Revenue Sector for the Year Ended 31 March 2019

Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Economic and Revenue Sector for the year ended 31 March 2019 GOVERNMENT OF GUJARAT (Report No. 3 of the year 2020) http://www.cag.gov.in TABLE OF CONTENTS Particulars Paragraph Page Preface vii Overview ix - xvi PART – I Economic Sector CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION About this Report 1.1 1 Audited Entity Profile 1.2 1-2 Authority for Audit 1.3 3 Organisational structure of the Office of the 1.4 3 Principal Accountant General (Audit-II), Gujarat Planning and conduct of Audit 1.5 3-4 Significant audit observations 1.6 4-8 Response of the Government to Audit 1.7 8-9 CHAPTER II – COMPLIANCE AUDIT AGRICULTURE, FARMERS WELFARE AND CO-OPERATION DEPARTMENT Functioning of Junagadh Agricultural University 2.1 11-32 INDUSTRIES AND MINES DEPARTMENT Implementation of welfare programme for salt 2.2 32-54 workers FORESTS AND ENVIRONMENT DEPARTMENT Compensatory Afforestation 2.3 54-75 PART – II Revenue Sector CHAPTER–III: GENERAL Trend of revenue receipts 3.1 77 Analysis of arrears of revenue 3.2 80 i Arrears in assessments 3.3 81 Evasion of tax detected by the Department 3.4 81 Pendency of Refund Cases 3.5 82 Response of the Government / Departments 3.6 83 towards audit Audit Planning and Results of Audit 3.7 86 Coverage of this Report 3.8 86 CHAPTER–IV: GOODS AND SERVICES TAX/VALUE ADDED TAX/ SALES TAX Tax administration 4.1 87 Results of Audit 4.2 87 Audit of “Registration under GST” 4.3 88 Non/short levy of VAT due to misclassification 4.4 95 /application of incorrect rate of tax Irregularities -

Annual Report 2018-19

Annual Report 2018-19 Shri Narendra Modi, Hon’ble Prime Minister of India launching “Saubhagya” Yojana Contents Sl No. Chapter Page No. 1 Performance Highlights 3 2 Organisational Set-Up 11 3 Capacity Addition Programme 13 4 Generation & Power Supply Position 17 5 Ultra Mega Power Projects (UMPPs) 21 6 Transmission 23 7 Status of Power Sector Reforms 29 8 5XUDO(OHFWULÀFDWLRQ,QLWLDWLYHV 33 ,QWHJUDWHG3RZHU'HYHORSPHQW6FKHPH ,3'6 8MMZDO'LVFRP$VVXUDQFH<RMDQD 8'$< DQG1DWLRQDO 9 41 Electricty Fund (NEF) 10 National Smart Grid Mission 49 11 (QHUJ\&RQVHUYDWLRQ 51 12 Charging Infrastructure for Electric Vehicles (EVs) 61 13 3ULYDWH6HFWRU3DUWLFLSDWLRQLQ3RZHU6HFWRU 63 14 International Co-Operation 67 15 3RZHU'HYHORSPHQW$FWLYLWLHVLQ1RUWK(DVWHUQ5HJLRQ 73 16 Central Electricity Authority (CEA) 75 17 Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) 81 18 Appellate Tribunal For Electricity (APTEL) 89 PUBLIC SECTOR UNDERTAKING 19 NTPC Limited 91 20 NHPC Limited 115 21 Power Grid Corporation of India Limited (PGCIL) 123 22 Power Finance Corporation Ltd. (PFC) 131 23 5XUDO(OHFWULÀFDWLRQ&RUSRUDWLRQ/LPLWHG 5(& 143 24 North Eastern Electric Power Corporation (NEEPCO) Ltd. 155 25 Power System Operation Corporation Ltd. (POSOCO) 157 JOINT VENTURE CORPORATIONS 26 SJVN Limited 159 27 THDC India Ltd 167 STATUTORY BODIES 28 Damodar Valley Corporation (DVC) 171 29 Bhakra Beas Management Board (BBMB) 181 30 %XUHDXRI(QHUJ\(IÀFLHQF\ %(( 185 AUTONOMOUS BODIES 31 Central Power Research Institute (CPRI) 187 32 National Power Training Institute (NPTI) 193 OTHER IMPORTANT -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Yamunanagar, Part XII A

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -8 HARYANA DISTRICT CEN.SUS HANDBOOK PART XII - A & B VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE &TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DISTRICT YAMUNANAGAR Direqtor of Census Operations Haryana Published by : The Government of Haryana. 1995 ir=~~~==~==~==~====~==~====~~~l HARYANA DISTRICT YAMUNANAGAR t, :~ Km 5E3:::a::E0i:::=::::i====310==::::1i:5==~20. Km C.O.BLOCKS A SADAURA B BILASPUR C RADAUR o JAGADHRI E CHHACHHRAULI C.D.BLOCK BOUNDARY EXCLUDES STATUTORY TOWN (S) BOUNDARIES ARE UPDATED UPTO 1.1.1990 W. R.C. WORKSHOP RAILWAY COLONY DISTRICT YAMUNANAGAR CHANGE IN JURI50lC TION 1981-91 KmlO 0 10 Km L__.j___l BOUNDARY, STATE ... .. .. .. _ _ _ DISTRICT _ TAHSIL C D. BLOCK·:' .. HEADQUARTERS: DISTRICT; TAHSIL; e.D. BLOCK @:©:O STATE HIGHWAY.... SH6 IMPORT ANi MEiALLED ROAD RAILWAY LINE WITH STATION. BROAD GAUGE RS RIVER AND STREAMI CANAL ~/--- - Khaj,wan VILLAGE HAVING 5000 AND ABOVE POPULATION WITH NAME - URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE-CLASS I,II,IV &V .. POST AND TElEGRAPH OFFICE. PTO DEGREE COLLEGE AND TECHNICAL INSTITUTION ... ••••1Bl m BOUNDARY, STATE DISTRICT REST HOUSE, TRAVELLERS' BUNGALOW, FOREST BUNGALOW RH TB rB CB TA.HSIL AND CANAL BUNGALOW NEWLY CREATED DISTRICT YAMuNANAGAR Other villages having PTO/RH/TB/FB/CB, ~tc. are shown as .. .Damla HAS BEEN FORMED BY TRANSFERRING PTO AREA FROM :- Western Yamuna Canal W.Y.C. olsTRle T AMBAl,A I DISTRICT KURUKSHETRA SaSN upon Survt'y of India map with tn. p.rmission of theo Survt'yor Gf'nf'(al of India CENSUS OF INDIA - 1991 A - CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS The publications relating to Haryana bear series No.