King's Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Underwater Photography

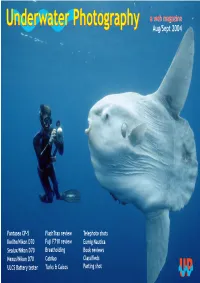

aa webweb magazinemagazine UnderwaterUnderwater PhotographyPhotography Aug/Sept 2004 Fantasea CP-5 FlashTrax review Telephoto shots Ikelite/Nikon D70 Fuji F710 review Eumig Nautica Sealux/Nikon D70 Breatholding Book reviews Nexus/Nikon D70 Cabilao Classifieds ULCS Battery tester Turks & Caicos Parting shot Issue 20/1 Digital solutions INON UK Four strobes for the digital enthusiast. Choose the features you need including auto exposure and modelling lights. Two wide angle lenses for shooting large Versatile arm system subjects. puts precision lighting Optional dome control at your fingertips. port lets you use EZ clamps hold strobe your existing securely in high current, yet lens for provide instant adjustment superwide angle for creativity. photography. Official INON UK distributors: Four macro lenses Ocean Optics put extreme close up photography within your 13 Northumberland Ave, London WC2N 5AQ capabilities. Available in Tel 020 7930 8408 Fax 020 7839 6148 screw thread or fast E mail [email protected] www.oceanoptics.co.uk Issue 20/2 mount bayonet fit. Contents UnderwaterUnderwater PhotographyPhotography 4 Editorial a web magazine 23 FlashTrax review 35 Cabilao Aug/Sept 2004 5 News & Travel e mail [email protected] 11 New products by Peter Rowlands 44 Telephoto 24 Fuji F710 review by Nonnoy Tan 17 Ikelite/Nikon D70 39 Turks & Caicos by Alexander Mustard 49 Eumig Nautica by Peter Rowlands by Steve Warren 27 Breatholding by Will Postlethwaite 21 Battery tester by Bernardo Sambra 52 Book reviews Cover by 54 Classifieds by Tony Matheis Phillip Colla by Phillip Colla 56 Parting shot by Tony Sutton Issue 20/3 U/w photo competitions motorways at weekends). -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,602,656 B1 Shore Et Al

USOO6602656B1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,602,656 B1 Shore et al. (45) Date of Patent: Aug. 5, 2003 (54) SILVER HALIDE IMAGING ELEMENT 5.998,109 A 12/1999 Hirabayashi WITH RANDOM COLOR FILTER ARRAY 6,117,627 A 9/2000 Tanaka et al. 6,387,577 B2 5/2002 Simons ......................... 430/7 (75) Inventors: Joel D. Shore, Rochester, NY (US); Krishnan Chari, Fairport, NY (US); FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS Dennis R. Perchak, Penfield, NY (US) JP 97145909 6/1997 (73) Assignee: Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, * cited by examiner NY (US) Primary Examiner John A. McPherson (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm Arthur E. Kluegel patent is extended or adjusted under 35 U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. (57) ABSTRACT Disclosed is an imaging element comprising a Single layer (21) Appl. No.: 10/225,608 containing a random distribution of a colored bead popula (22) Filed: Aug. 22, 2002 tion of one or more colors coated above one or more layers a 149 comprising light Sensitive Silver halide emulsion grains, (51) Int. Cl." ............................ G02B 5/20; G03C 1/825 wherein the population comprises beads of at least one color (52) U.S. Cl. .................. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 430/511; 430/7 in which at least 25% (based on projected area) of the beads (58) Field of Search ... - - - - - - - - - - - - 430/511, 7 of that color have an ECD less than 2 times the ECD of the Silver halide grains in Said one emulsion layer or in the (56) References Cited f emulsion layer in the case of more than one emulsion ayer U.S. -

Killed Polaroid ?

Who Killed Polaroid ? Copyright Michael E. Gordon 2010 The Polaroid Corporation had been one of the most exciting, controversial and misunderstood companies of all time. Some might argue that it was seriously mismanaged throughout its convoluted history. Others might believe that its "growing pains" were unavoidable and to be expected for a $ 2.3 billion cutting-edge technology company. Polaroid filed for bankruptcy in 2001 and was dismembered, piece by painful piece. The remainder of the Company was acquired by an investment group in 2002, sold again to another investment group, and finally laid to rest permanently. Did this just happen, or did someone kill Polaroid? The Polaroid Corporation was founded in 1937 by Dr. Edwin Land (1909 – 1991) to commercialize his first product: polarizing light material. This unique 3-layered sheet structure found use in light control, glare reduction, 3D movies, and a variety of military applications such as goggles, smart bombs and target finders. Land was in his late 20s when he launched Polaroid. During the Second World War, the company grew rapidly. By 1949, under the relentless leadership of Dr. Land, Polaroid had developed and commercialized the Land Camera - the first instant black and white camera and film system capable of producing exceptional photos in 60 seconds. This was followed by several other break-through products, including the instant color peel- apart system (1963); SX-70 absolute on-step color photography (1972); and the Polavision instant movie camera, film and projector system (1975). Polavision was a financial disaster (-$500M) due to the complexity of the technology and the simultaneous emergence of magnetic video Dr. -

Newsletter-Q4 2020

NewsLetter Newsletter Team: E. Foote, M. Hall, E. Kliem, W. Rosen October - December [email protected] Polaroid Retirees Association 2020 THIS PUBLICATION IS SOLELY FOR THE USE OF THE PRA MEMBERSHIP POLAROID RETIREES ASSOCIATION, INC. P.O. BOX 541395, WALTHAM, MA 02454-1395 WEB SITE ADDRESS WWW.POLAROIDRETIREES.ORG Letter from the President Dear PRA members and alumnae of the finest corporation one could ask to be employed by, Board of We were led by a genius with vision, entrepreneurial excellence and a unique concern that all the employees of the corporation be afforded the opportunity to grow in depth and broadness Directors of knowledge. He was special and the company reflected this uniqueness in an extraordinary & Officers way. Which one of us was not better off leaving Polaroid than when we joined the company? My name is Ed Wade and I am the new president of the PRA, Polaroid Retirees Association, President replacing Elizabeth Foote who for past year led the Board of Directors of the PRA. Elizabeth Ed Wade led us in a manner where all issues and concerns were addressed and resolved while maintain- ing the pleasant atmosphere of care and concern, sustaining the Polaroid culture. 1st Vice President John Flynn I spent 31 years at Polaroid, mainly involved with Film Manufacturing and Industrial Products, often travelling to Scotland, Holland and Mexico, an extraordinary experience working with 2nd Vice President and meeting many members that I now consider friends and associates. The PRA is a venue Arthur Aznavorian that enables us to sustain these relationships through our business and luncheon meetings held twice annually. -

Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All Rights Reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 7

Memorial Tributes: Volume 7 EDWIN HERBERT LAND 128 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 7 EDWIN HERBERT LAND 129 EDWIN HERBERT LAND 1909–1991 WRITTEN BY STANLEY H. MERVIS SUBMITTED BY THE NAE HOME SECRETARY EDWIN HERBERT LAND—inventor, scientist, entrepreneur, teacher, visionary, and public servant—was born in Bridge-port, Connecticut, on May 7, 1909, and died in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on March 1, 1991, at the age of eighty-one. He was educated at the Norwich Academy and Harvard University. While still a freshman at Harvard, Land was intrigued with the natural phenomena of polarized light and was challenged simultaneously by the difficulty of using it in science and the impossibility of using it in applied science for industry because the then-available light polarizers were Nicol prisms, large single crystals, heavy, expensive, and necessarily limited in size. There were no "sheet" polarizers. Land conceived the idea of making in sheet form the optical equivalent of a large, single crystal by suspending submicroscopic polarizing particles in plastic or glass and orienting these polarizing particles in a transparent sheet. Following a leave of absence to pursue his ideas, he returned to Harvard bringing with him his new light polarizer. In 1932 at a Harvard physics colloquium he announced a "new polarizer for light in the form of an extensive synthetic sheet," a polarizer known as "J-sheet." He later took another leave of absence to devote himself entirely to research in polarized light. Although he never graduated, Land returned to Harvard on many occasions as a lecturer, and to receive an honorary doctor of science degree in 1957. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,607,873 B2 (*) Notice

USOO66O7873B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,607,873 B2 Chari et al. (45) Date of Patent: Aug. 19, 2003 (54) FILM WITH COLOR FILTER ARRAY 4,971,869 A 11/1990 Plummer 6,117,627 A 9/2000 Tanaka et al. (75) Inventors: Krishnan Chari, Fairport, NY (US); Sidney J. Bertucci, Rochester, NY FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (US); Michael J. Simons, Ruislip (GB) DE 1811 983 6/1970 EP O 935 168 A2 8/1999 (73) Assignee: Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS (*)* ) Notice: Subject tot any disclaidisclaimer, the tterm off thisthi AyrM. J. Simons, USSN “Method00sossi of (DSO552)Making a Random id Mar Color 15, 2001.Filter past isis''S alusted under 35 M. J. Simons, “Film With Random Color Filter Array”, a -- y yS. USSN 09/808,873 (D-80554) filed Mar. 15, 2001. M. J. Simons, “Random Color Filter Array”, USSN 09/810, (21) Appl. No.: 09/922,273 787 (D-80555) filed Mar. 16, 2001. (22) Filed: Aug. 3, 2001 * cited by examiner (65) Prior Publication Data Primary Examiner John A. McPherson US 2003/0054264 A1 Mar. 20, 2003 (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm Arthur E. Kluegel (51) Int. Cl. ........................... G03C 1/825; G02B5/20 (57) ABSTRACT (52) U.S. Cl. ............................................ 430/511; 430/7 (58) Field of Search ...................................... so. 511 aDisclosed light Sensitive is a color layer, film and comprising (3) a water (1) permeable a support color layer, filter (2) (56) References Cited array (CFA) layer comprising a continuous phase transpar ent binder containing a random distribution of colored U.S. -

Docusext Bemis

DOCUSEXT BEMIS ED 200 724 028 401 AUTHOR Knox, Kathleen TITLE Polaroid Corporation's TuitionAssistance elan: A Case Study. Worker Education andTraining Policies Project. INSTITUTION National Inst. for Work and Learning,Washington, D.C. %BONS AGENCI National Inst. of Education(DHEW) Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Sep 79 CONTRACT 400-76-0125 NOTE 60p.: For related documentssee CE 028 398-412. AVAILABLE FROM National Institute for Work andLearning, Suite 301, 1211 Connecticut Ave N.W. Washington, DC 20036 (Order No.: CS3, $5.50). EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage_. PC Not Availablefrom EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Adult Education: Case Studies;Educational Opportunities: Employer Attitudes;*Enrollment: Higher Education; IndustrialTraining: *Labor Education; *Motivation Techniques;On the Job Training: Postsecondary Education;Professional Personnel: Professional Training:Skilled Workers: Supervisory Training: TechnicalEducation; *Trade and Industrial Education; TrainingAllowances; *Tuition Grants IDENTIFIERS *Polaroid Corporation ABSTRACT A study was conducted to determinethe factors that account for the sustained and unusually high rate of participationin tuition-assisted education byPolaroid employees. Informationas gathered by interviews with Polaroidmanagement officials in the Human Resources Development Group:staff of the Education andCareer Planning Department; and employeeswho have participated in the program: review of internal policy: andlibrary research. The study examines the structure, provisions,and administration of thecompany plan; the experience and motivationsof plan managers and plan participants: and the corporatecontext in which the plan operates. Findings show that thecompany has a systematic and comprehensive series of courses and programs for itshourly and salaried employees, including internal and externalprograms, organizational development, and career and education counseling.The Tuition Assistance Plan is an integrated component of this overallemployee development program. -

Wunderkino Ii-Final Schedule Of

13th Annual Northeast Historic Film Summer Symposium Wunderkino II On the Varieties of Cinematic Experience July 26-28, 2012 (“National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC” courtesy of Mark Neumann) Wunderkino (“wonder-cinema”) are moving images that ignite our curiosity by engaging, and helping us to rethink questions about creativity, complexity, rarity, and the multiple uses and understandings we may find in amateur and non-commercial films. The 2012 Northeast Historic Film (NHF) Summer Symposium revisits the idea of Wunderkino to inform and expand our understanding of amateur and non-theatrical film. In 2011, the NHF Summer Symposium focused on assembling a “cabinet of cinematic curiosities.” This year we draw from the wide range of approaches that scholars, artists, filmmakers, and archivists are bringing to the study and use of amateur and non-theatrical film. SCHEDULE OF PRESENTATIONS Thursday July 26 6:30 PM Opening Reception Screenings From NHF Getting Your Snacks Straight: Intermission Reels from NHF’s Donald C. Brown Jr. Collection Walter Forsberg—Moving Image Archiving and Preservation Program, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University, New York City, NY More than mere ‘Coming Attractions’-style teaser trailers for upcoming feature films, the snipe film category encompasses such assorted skeletal trailer reel elements, as: ‘tags’ and ‘daters’; concessions advertisements; theatre policy notices; holiday well- wishing messages from local businesses; Soundie-style musical interludes; and, countdown clocks—essentially everything other than the promos for feature films that one generally associates with the term, ‘trailer.’ Snipes, these “other” kinds of trailers, are an oft-overlooked genre of independent and industrial film. -

Small-Gauge and Amateur Film Bibliography Edited by Margaret A

Small-Gauge and Amateur Film Bibliography Edited by Margaret A. Compton. Compiled by Margaret A. Compton, Katie Trainor, Karan Sheldon, Dwight Swanson, and William O’Farrell This bibliography has its genesis in the Association of Moving Image Archivists (AMIA) Small Gauge Task Force formed in 2000. In preparation for AMIA’s 2001 conference held in Portland, Oregon, which emphasized small-gauge film, Sheldon (Northeast Historic Film) and Trainor (then with the George Eastman House’s film preservation school) compiled the original bibliography with input from Compton (University of Georgia Media Archives). Many entries came from Alan Kattelle’s library, which Trainor was cataloguing. Compton expanded with O’Farrell (National Archives of Canada) and Swanson (Northeast Historic Film). The purpose was to offer a starting place for archivists and researchers interested in understanding amateur and small-gauge moving images. The objectives were to round up the first-ever overview of books and periodicals in the field, to share information on publications collected by institutions and individuals, and to foster new scholarship. The bibliography makes clear that, from the earliest days of cinema, non-professionals had an interest in making their own films, documenting their own lives, and telling stories on film. Although movie studios were leading the way, numerous publications directed the amateur into the world of cameras, film stock, scenario writing, and other production details. The field grew rapidly and stayed constant for decades, with only a slight drop in publications during World War II, as well as a drop after home video gained popularity. Many of the books listed are out of print or were unavailable for review. -

Industria, Manifattura, Artigianato

SIRBeC scheda PSTRL - ST110-00476 Polaroid Polavision Land Player - visore di pellicole Polavision - Industria, manifattura, artigianato Polaroid Corporation Link risorsa: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/scienza-tecnologia/schede/ST110-00476/ Scheda SIRBeC: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/scienza-tecnologia/schede-complete/ST110-00476/ SIRBeC scheda PSTRL - ST110-00476 CODICI Unità operativa: ST110 Numero scheda: 476 Codice scheda: ST110-00476 Visibilità scheda: 2 Utilizzo scheda per diffusione: 03 Tipo scheda: PST Livello ricerca: C CODICE UNIVOCO Codice regione: 03 Numero catalogo generale: 01970110 Ente schedatore: R03/ Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia "Leonardo da Vinci" Ente competente: S27 RELAZIONI RELAZIONI CON ALTRI BENI Tipo relazione: correlazione Tipo scheda: PST Codice bene: 0301970092 Codice IDK della scheda correlata: ST110-00603 ALTRI CODICI Altro codice: COMFTC/MNST OGGETTO OGGETTO Definizione: visore di pellicole Polavision Denominazione: Polaroid Polavision Land Player CATEGORIA Pagina 2/7 SIRBeC scheda PSTRL - ST110-00476 Categoria principale: Industria, manifattura, artigianato Altra categoria: Fotografia Parole chiave: movie camera LOCALIZZAZIONE GEOGRAFICO-AMMINISTRATIVA LOCALIZZAZIONE GEOGRAFICO-AMMINISTRATIVA ATTUALE Stato: Italia Regione: Lombardia Provincia: MI Nome provincia: Milano Codice ISTAT comune: 015146 Comune: Milano COLLOCAZIONE SPECIFICA Denominazione struttura conservativa - livello 1: Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia "Leonardo da Vinci" CRONOLOGIA CRONOLOGIA -

Polaroid's Polavision, 1977–1980

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1162/GREY_a_00210 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Balsom, E. (2017). Instant Failure: Polaroid's Polavision, 1977–80. Grey Room, 66, 6-31. https://doi.org/10.1162/GREY_a_00210 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

The Reproduction of Colour RWG HUNT

The Reproduction of Colour R.W.G. HUNT Visiting Professor of Colour Science at the University of Derby Formerly Assistant Director of Research, Kodak Limited, Harrow The Reproduction of Colour When the rainbow appears in the clouds, I will see it and remember the everlasting covenant between Me and all living beings on earth. Genesis 9:16 Wiley–IS&T Series in Imaging Science and Technology Series Editor: Michael A. Kriss Formerly of the Eastman Kodak Research Laboratories and the University of Rochester Reproduction of Colour (6th Edition) R. W. G. Hunt Colour Appearance Models (2nd Edition) Mark D. Fairchild Published in Association with the Society for Imaging Science and Technology The Reproduction of Colour R.W.G. HUNT Visiting Professor of Colour Science at the University of Derby Formerly Assistant Director of Research, Kodak Limited, Harrow Copyright © 2004 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (+44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com First Published 1957, revised 1961. Second Edition 1967. Third Edition 1975. Fourth Edition 1987. Fifth Edition 1995. © Robert Hunt All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher.