The Rise and Fall of Lost Weekend: a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRAG AV BERGENSFELTETS KVART ÆRGEOLOGI. I Dette Arbeid Vil V-Esentlig Dr·Eie Seg Om Strøket Umiddelbart Nord for Bergen (Fig

NORSK GEOLOGISK TIDSSKRIFT 25 433 Ms. mott. l. desem ber 1944. DRAG AV BERGENSFELTETS KVART ÆRGEOLOGI. I AV ISAK UNDÅS Med 8 fig. Innledning. Dette arbeid vil v-esentlig dr·eie seg om strøket umiddelbart nord for Bergen (fig. 1), der jeg har noen få observasjoner av merkene etter seing-lasiale ·og postglas:ia·le nivåer. Feltet har vært besøkt av en rekke geo'log-er, som har målt høgdene av ter.rass·er, strandlinjer og strandflate (·se litteraturlisten). Det har vært divergerende meninger om karakteren av strøkets mest iøynefaHende strandlinje, om gangen av de seinglasia•le og postglasiai·e nivåer, om høgda av strantdflata og om årsaken til f.eltets nåværende ytformer. O bservas j on er. Jeg henviser til! nedenstå.ende tabell når de't gjel der mårlte :høgder av terrasser, strandrvoHer, strandlinjer o. ri. og nevner ellers bare avrundete tall og noen få viktigere steder i den orden de forekommer i tabell og profil. Ytterst i Øygarden 1 er det l-ite av morene og botnmorene, som sjøen lett kan sette merker i; derfor har ingen før angitt noen sikker marin grense der. En har ikke vært sikker på om isen gikk ut over Øygarden i sist·e istid (7]; men etter det som er funnet på Blomøy både av avleiringer, morener og slmrings striper (fig. 2), er det g-itt at isen da gikk ut over Øygarden. Vest ligst på Blomøy fins det nemlig en utvasket morenerekke, som har retning noenlunde loddrett på de skuringsstriper som ennå kan sees på østskråni·ngen av Blommeknuten. Den lågeste marine grense finner en på Sæløy nordligst i Øy garden, der brenningsgrensa rekker bar.e 26 m o. -

Årsrapport 2019 Askøy Kirkelige Fellesråd

2019 Årsrapport Herdla barnekor sammen med Berit Håpoldøy, synger for Kongen Geir Viksund Askøy kirkelige fellesråd 31.12.2019 1 Innhold ............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 ÅRET 2019 I KORTE TREKK ................................................................................................................................... 2 OPPGAVENE TIL ASKØY KIRKELIGE FELLESRÅD. .............................................................................................. 3 DRIFTSMESSIGE HOVEDPUNKTER ....................................................................................................................... 4 PERSONALINNSATS 2019: ................................................................................................................................... 4 AVDELINGENE/PERSONALGRUPPENE: .............................................................................................................. 5 GRAVPLASSAVDELINGEN: ............................................................................................................................. 5 KIRKETJENER/RENHOLDSSTILLINGENE: .......................................................................................................... 5 TROSOPPLÆRING: .......................................................................................................................................... 5 UNGDOMSARBEIDER OG UNGDOMSPREST: .............................................................................................. -

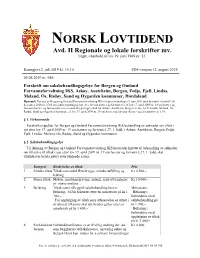

PDF-Versjon 12

NORSK LOVTIDEND Avd. II Regionale og lokale forskrifter mv. Utgitt i henhold til lov 19. juni 1969 nr. 53. Kunngjort 2. juli 2019 kl. 14.10 PDF-versjon 12. august 2019 05.06.2019 nr. 946 Forskrift om saksbehandlingsgebyr for Bergen og Omland Farvannsforvaltning IKS, Askøy, Austrheim, Bergen, Fedje, Fjell, Lindås, Meland, Os, Radøy, Sund og Øygarden kommuner, Hordaland Hjemmel: Fastsatt av Bergen og Omland Farvannsforvaltning IKS v/representantskapet 5. juni 2019 med hjemmel i forskrift 20. desember 2010 nr. 1760 om saksbehandlingsgebyr etter lov om havner og farvann § 1, jf. lov 17. april 2009 nr. 19 om havner og farvann (havne- og farvannsloven) § 6 samt delegeringsvedtak fra Askøy, Austrheim, Bergen, Fedje, Fjell, Lindås, Meland, Os, Radøy, Sund og Øygarden kommune, jf. lov 17. april 2009 nr. 19 om havner og farvann (havne- og farvannsloven) § 10. § 1. Virkeområde Forskriften gjelder for Bergen og Omland Farvannsforvaltning IKS behandling av søknader om tiltak i sjø etter lov 17. april 2009 nr. 19 om havner og farvann § 27, 1. ledd, i Askøy, Austrheim, Bergen, Fedje, Fjell, Lindås, Meland, Os, Radøy, Sund og Øygarden kommuner. § 2. Saksbehandlingsgebyr Til dekning av Bergen og Omland Farvannsforvaltning IKS kostnader knyttet til behandling av søknader om tillatelse til tiltak i sjø, etter lov 17. april 2009 nr. 19 om havner og farvann § 27, 1. ledd, skal tiltakshaver betale gebyr etter følgende satser: Kategori Beskrivelse av tiltak Pris 1 Mindre tiltak Tiltak som enkel flytebrygge, mindre utfylling og Kr 4 500,– ledning 2 Større tiltak Moloer, mudring/graving, anlegg, samt utbygginger Kr 10 000,– av større omfang 3 Befaring Tiltak som i tillegg til saksbehandling krever Minstesats: befaring, vil bli fakturert etter en minstesats på kr 1 Befaring i 700,–. -

Naturressurskartlegging I Kommunene Sund, Fjell Og Øygarden

Naturressurskartlegging i kommunene Sund, Fjell og Øygarden: Miljøkvalitet i vassdrag Rapport nr. 93, november 1993. Naturressurskartlegging i kommunene Sund, Fjell og Øygarden: Miljøkvalitet i vassdrag. Geir Helge Johnsen og Annie Bjørklund Rapport nr. 93, november 1993. RAPPORTENS TITTEL: Naturressurskartlegging i kommunene Sund, Fjell og Øygarden: Miljøkvalitet i vassdrag. FORFATTERE: Dr.philos. Geir Helge Johnsen og cand.scient. Annie Bjørklund OPPDRAGSGIVER: Sund, Fjell og Øygarden kommuner. OPPDRAGET GITT: ARBEIDET UTFØRT: RAPPORT DATO: 15.juni 1993 August - oktober 1993 3.november 1993 RAPPORT NR: ANTALL SIDER: ISBN NR: 93 75 ISBN 82-7658-013-0 RAPPORT SAMMENDRAG: Foreliggende informasjon vedrørende miljøkvalitet i vassdragene er sammenstilt og vurdert med hensyn på brukskvalitet. Opplysningene er hentet fra mange kilder, men det meste av vannkvalitetsinformasjonen er fra de rutinemessige drikkevannsundersøkelsene. Regionen er rik på småvassdrag, men forsuringen truer en lang rekke av fiskebestandene,- med unntak av vannkilder der det ennå finnes bufferkapasitet igjen. Enkelte brukeres "monopolisering" av hele vassdrag skaper også problem, ved at demninger eller andre stengsler hindrer annen utnyttelse av ressursene. Drikkevannskvaliteten i regionen er i utgangspunktet heller ikke god. Vannet fra de aller fleste råvannskildene bør alkaliseres, men særlig problematisk er det høye innholdet av humusstoffer. Dette medfører problemer av estetisk karakter, og skaper til dels betydelige problemer for de vanligste desinfiseringsmetodene. -

Onshore Power Supply for Cruise Vessels – Assessment of Opportunities and Limitations for Connecting Cruise Vessels to Shore Power

Onshore Power Supply for Cruise Vessels – Assessment of opportunities and limitations for connecting cruise vessels to shore power Vidar Trellevik © 04.01.2018 GREEN CRUISE PORT is an INTERREG V B project, part-financed by the European Union (European Regional Development Fund and European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument). ONSHORE POWER SUPPLY FOR CRUI SE VESSELS Assessment of opportunities and limitations for connecting cruise vessels to shore power Bergen og Omland Havnevesen Report No.: 2017-1250 Rev. 0.1 Document No.: 113LJAJL-1 Date: 2018-01-04 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................. 3 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................... 4 2 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 6 Background 6 Abbreviation list 7 3 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................ 7 4 GENERAL ON ONSHORE POWER SUPPLY .......................................................................... 8 System and technology description 8 Shore connection standards 10 5 INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENTS AND REGULATI ONS ...................................................... 11 International policy and regulations 11 EU regulations and incentives 12 6 CALCULATI ON PAPAMETERS ........................................................................................ -

“Quiet Please, It's a Bloody Opera”!

UNIVERSITETET I OSLO “Quiet Please, it’s a bloody opera”! How is Tommy a part of the Opera History? Martin Nordahl Andersen [27.10.11] A theatre/performance/popular musicology master thesis on the rock opera Tommy by The Who ”Quiet please, it’s a bloody opera!” Martin Nordahl Andersen 2011 “Quiet please, it’s a bloody opera!” How is Tommy part of the Opera History? Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo All photos by Ross Halfin © All photos used with written permission. 1 ”Quiet please, it’s a bloody opera!” Aknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors Ståle Wikshåland and Stan Hawkins for superb support and patience during the three years it took me to get my head around to finally finish this thesis. Thank you both for not giving up on me even when things were moving very slow. I am especially thankful for your support in my work in the combination of popular music/performance studies. A big thank you goes to Siren Leirvåg for guidance in the literature of theatre studies. Everybody at the Institute of Music at UiO for helping me when I came back after my student hiatus in 2007. I cannot over-exaggerate my gratitude towards Rob Lee, webmaster at www.thewho.com for helping me with finding important information on that site and his attempts at getting me an interview with one of the boys. The work being done on that site is fantastic. Also, a big thank you to my fellow Who fans. Discussing Who with you makes liking the band more fun. -

Dioxins and PCB Analysis of Chicken Eggs and Cows Milk from Designated Norwegian Regional Areas (2014-2017) Report to Norwegian Food Safety Authority April 2018

Dioxins and PCB Analysis of Chicken Eggs and Cows Milk from Designated Norwegian Regional Areas (2014-2017) Report to Norwegian Food Safety Authority April 2018 Authors: R.G. Petch, T. Griffiths Quality statement: All results created by fera were quality checked and approved prior to release to NFSA. Information relating to the origin of the samples (place and date of collection) is as provided by sampling staff and has not undergone verification checks by Fera. Contents ________________________________________ Glossary of Main Terms……………………………………… 3 Executive Summary …………………………………………... 4 1. Background…………………………………………………. 6 2. Method………………………………………………………. 8 2.1 Sample Collection and Preparation…………………………… 8 2.2 Contaminants measured – Specific Analytes………………... 8 2.3 PCDD/F and PCB - Analytical Methodology…………………. 8 3. Results………………………………………………………. 10 4. Conclusion………………………………………………….. 12 5. References………………………………………………….. 13 Table 1: Overview of Samples………………………………. 15 Fig 1: District Map of Norway………………………………… 17 Fig 2: Regional Map of Norway……………………………… 18 Appendix 1: Analytical data for MILK……………………….. 19 Appendix 2: Analytical data for EGGS……………………… 26 Dioxins and PCB Analysis of Chicken Eggs and Cows Milk from Designated Norwegian Regional Areas (2014-2017) Report to Norwegian Food Safety Authority (NFSA) Glossary of Main Terms Term or General Meaning Of Term Acronym EU European Union EC European Commission NFSA Norwegian Food Safety Authority WHO World Health Organisation PCB Polychlorinated biphenyl Ortho -PCB Ortho-substituted PCB (non planar) Non -ortho -PCB Non -ortho -substituted PCB (co -planar) DL-PCB Dioxin-Like PCB (Toxicity Similar to that of Dioxins) PCDD/F Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin/ polychlorinated dibenzofuran (dioxins) Toxic Equivalency Factor – toxicity expressed for each dioxin-like compound as a TEF fraction of 2,3,7,8 -TCDD (2,3,7,8 -TCDD = 1). -

Kommunedelplan for Sambandet Vest Silingsrapport

Kommunedelplan for Sambandet vest Silingsrapport Askøy kommune og kommunane Meland, Radøy og Lindås (Alver kommune i 2020): KOMMUNEDELPLAN FOR SAMBANDET VEST VEDLEGG I: SILINGSRAPPORT, juni 2019 1 Kommunedelplan for Sambandet vest Silingsrapport Oppdragsgjevar: Alver kommune Oppdragsgjevars kontaktperson: John Fredrik Wallace Rådgjevar Norconsult AS, Valkendorfsgate 6, NO-5012 Bergen Oppdragsleiar: Øystein Skofteland Fagansvarleg: Øystein Skofteland Andre nøkkelpersonar: Alv Terje Fotland, Lene Merete Rabben, Kristoffer Åsen Røys, Heidi Handeland, Arne Værnes. Kristina Ebbing Wensaas Oppdragsnummer NO: 5190526 001 2019-05-22 Silingsrapport Versjon 1 OYSKO ATFOT/KRIWEN OYSKO Versjon Dato Beskrivelse Utarbeidet Fagkontrollert Godkjent Dette dokumentet er utarbeidet av Norconsult AS som del av det oppdraget som dokumentet omhandler. Opphavsretten tilhører Norconsult AS. Dokumentet må bare benyttes til det formål som oppdragsavtalen beskriver, og må ikke kopieres eller gjøres tilgjengelig på annen måte eller i større utstrekning enn formålet tilsier. 2 Kommunedelplan for Sambandet vest Silingsrapport INNHALD 1 INNLEIING 5 4.3 FORKASTA LINJER 16 4.4 OPPSUMMERING 19 1.1 BAKGRUNN 5 5 ANALYSAR 21 2 MÅL MED PROSJEKTET 7 5.1 TRANSPORT, BUSETNAD OG ARBEIDSLIV 21 2.1 NASJONALE OG REGIONALE MÅL 7 5.2 TRAFIKK 27 2.2 SAMFUNNSMÅL 7 5.3 KOSTNAD 28 2.3 EFFEKTMÅL 8 5.4 KONFLIKTANALYSE 29 2.4 VEGSTANDARD 9 5.5 AREALPLANAR I OMRÅDET 33 3 METODE 11 6 SILING 35 3.1 SILINGSKRITERIUM OG SILING 11 6.1 KORRIDOR AA 35 3.2 VURDERING AV MÅLOPPNÅING 12 6.2 KORRIDOR -

Konseptvalgutredning Bergen Og Omland 2020

Konseptvalgutredning Bergen og omland November 2020 Konseptvalgutredning Bergen og omland 2020 Forord Det er mange og store planer for forbruk i Bergen og omland. I tillegg er det allerede i dag svak forsyningssikkerhet i området, og en aldrende anleggsmasse med stort reinvesteringsbehov. Med bakgrunn i dette besluttet Statnett på forsommeren 2019 å lage en konseptvalgutredning for Bergen og omland. Konseptvalgutredningen (KVU) er utarbeidet etter gjeldene forskrift og tilhørende veileder fra Olje- og energidepartmentet. Oslo Economics har gjennomført den eksterne kvalitetssikringen. Formålet med KVU og kvalitetssikringen er å styrke energimyndighetenes styring med konseptvalget, synliggjøre behov og valg av hovedalternativ samt å sikre at den faglige kvaliteten på de underliggende dokumenter i beslutningsunderlaget er god. Konseptvalgutredningen er utarbeidet i dialog med BKK Nett som er regionalt utredningsansvarlig for området. Statnett er ansvarlig for kraftnettet på 300 og 420 kV spenningsnivå, og BKK Nett er ansvarlig for 132 kV og lavere spenningsnivå. En god og tett dialog har vært viktig for å synliggjøre behovet for å gjøre tiltak, og for å verifisere at vi har vurdert relevante konsepter. Statnett ønsker å legge til rette for en elektrisk fremtid. Nettiltak har lang ledetid, og forbruk har ofte kortere ledetid. For å kunne legge til rette for en potensielt høy forbruksvekst i Bergen og omland, anbefaler Statnett et konsept som innebærer en tredje forbindelse til Kollsnes. Videre vil vi starte å planlegge for å oppgradere eksisterende nett. I det videre arbeidet med planlegging av tiltak i Bergen og omland er det viktig med et tett samarbeid med forbruksaktørene og BKK Nett for å sikre at våre beslutninger er godt koordinert med deres planer. -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Den 40. Kortfilmfestivalen 14.–18. Juni 2017 Den 40. Kortfilmfestivalen 14

Den 40. 2017 Kortfilmfestivalen Den 40. Kortfilmfestivalen The 40th Norwegian Short Film Festival 14.–18. juni 2017 14–18 June 2017 Den 40. The 40th Norwegian Kortfilmfestivalen Short Film Festival Grimstad 14.–18. juni 2017 Grimstad 14–18 June 2017 Velkommen til den 40. Kortfilmfestivalen! Det er med forventning og stor entusiasme vi ønsker den kunstneriske filmens plass i dag. Hva betyr det å velkommen til den 40. utgaven av Kortfilmfestivalen. Vi har være bærekraftig? Hvordan jobber man med kunstneriske en lang rekke enestående filmer å by på i dette jubileums- prosesser innenfor dagens rammeverk og filmpolitikk? året, filmer vi har frydet oss over under utvelgelsen og som Selv om vi feirer 40 i år, er det i Kortfilmfestivalens ånd vi vet vil berøre vårt filmelskende publikum. Som alltid er det å se framover og belyse hva som rører seg i vår samtid bredde, variasjon og nyskapning innen film som står i fokus og se på hvordan dette kommer til uttrykk gjennom film. for oss, slik det har vært helt siden Kortfilmfestivalen fødtes i Programkomiteens arbeid har helt tydelig vært preget av Røros og vokste opp i Trondheim. tidsånden, med teknologiske kvantesprang, storpolitikk og De siste 30 årene har det vært i Grimstad at de nye globalisering som en stor del av nyhetsbildet. Under para- talentene oppdages, at karrierer skyter fart og nye partner- plyen Ny virkelighet vil vi nærme oss de store spørsmålene: skap oppstår. Grimstad, en kort uke i juni, har alltid vært en Hvordan påvirkes folk flest av ny teknologi? Hvilke aktører yngleplass for filmbransjen i Norge. -

![Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, England (FM)[MP3-320];124 514 KB](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9839/sadlers-wells-theatre-london-england-fm-mp3-320-124-514-kb-3039839.webp)

Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, England (FM)[MP3-320];124 514 KB

10,000 Maniacs;1988-07-31;Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, England (FM)[MP3-320];124 514 KB 10,000 Maniacs;Eden's Children, The Greek Theatre, Los Angeles, California, USA (SBD)[MP3-224];150 577 KB 10.000 Maniacs;1993-02-17;Berkeley Community Theater, Berkeley, CA (SBD)[FLAC];550 167 KB 10cc;1983-09-30;Ahoy Rotterdam, The Netherlands [FLAC];398 014 KB 10cc;2015-01-24;Billboard Live Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan [MP3-320];173 461 KB 10cc;2015-02-17;Cardiff, Wales (AUD)[FLAC];666 150 KB 16 Horsepower;1998-10-17;Congresgebow, The Hague, Netherlands (AUD)[FLAC];371 885 KB 16 Horsepower;2000-03-23;Eindhoven, Netherlands (Songhunter)[FLAC];514 685 KB 16 Horsepower;2000-07-31;Exzellenzhaus, Sommerbühne, Germany (AUD)[FLAC];477 506 KB 16 Horsepower;2000-08-02;Centralstation, Darmstadt, Germany (SBD)[FLAC];435 646 KB 1975, The;2013-09-08;iTunes Festival, London, England (SBD)[MP3-320];96 369 KB 1975, The;2014-04-13;Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival (SBD)[MP3-320];104 245 KB 1984;(Brian May)[MP3-320];80 253 KB 2 Live Crew;1990-11-17;The Vertigo, Los Angeles, CA (AUD)[MP3-192];79 191 KB 21ST CENTURY SCHIZOID BAND;21st Century Schizoid Band;2002-10-01;Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, England [FLAC];619 21ST CENTURY SCHIZOID BAND;21st Century Schizoid Band;2004-04-29;The Key Club, Hollywood, CA [MP3-192];174 650 KB 2wo;1998-05-23;Float Right Park, Sommerset, WI;Live Piggyride (SBD)(DVD Audio Rip)[MP3-320];80 795 KB 3 Days Grace;2010-05-22;Crew Stadium , Rock On The Range, Columbus, Ohio, USA [MP3-192];87 645 KB 311;1996-05-26;Millenium Center, Winston-Salem,