The Development of Urban Poetics in Roman Satire A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEGO® Sonic Mania™: from Idea to Retail Set

LEGO® Sonic Mania™: From Idea to Retail Set Sam Johnson’s first reaction when he saw that the LEGO Group may be designing a new set based on SEGA’s® beloved Sonic the Hedgehog™ was elation, that was followed quickly by a sense of dread. “The first game I had was Sonic the Hedgehog,” said Johnson, who is the design manager on the LEGO Ideas® line. “So immediately that kind of childhood connection kicks in and you have all these nostalgic feelings of, 'I really hope this goes through and I really want to be a part of it if it does.’ And then I had this dread of, ‘Well, how are we going to make Sonic?" Earlier this month, the LEGO Group announced it was in the process of creating a Sonic the Hedgehog set based on a concept designed by 24-year-old UK LEGO® superfan Viv Grannell. Her creation was submitted through the LEGO Ideas platform where it received 10,000 votes of support from LEGO fans. The next step was the LEGO Group reviewing her project among the many others that make it past that initial hurdle to see if it should be put into production. Johnson said he found Grannell’s build charming. “It’s so much in the vein of the actual video game itself which has this kind of colorful charm to it,” he said. “And it's not over complicated, which I really loved. Sonic has this real geometric design to it where the landscape is very stripey and you have these like square patterns on it. -

Daily Coin Relief!

DAILY COIN RELIEF! A BLOG FOR ANCIENT COINS ON THE PAS BY SAM MOORHEAD & ANDREW BROWN Issue 6 by Andrew Brown – 24 March 2020 Trajan and Dacia Often coins recorded through the PAS hint at or provide direct links to the wider Roman world. This can be anything from depictions of the Emperors, through to places, key events, battles, and even architecture. Good examples of this are seen in the coinage of Trajan (AD 98- 117), particularly in relation to his two military campaigns in Dacia – the landscape of modern-day Romania and Moldova, notably around the Carpathian Mountains (Transylvania) – in AD 101-102 and AD 105-106. Dacia, with her king Decebalus, was considered a potential threat to Rome as well as a source of great natural wealth, particularly gold. Trajan’s victorious Dacian Wars resulted in the southern half of Dacia being annexed as the Roman Marcus Ulpius Traianus province of Dacia Traiana in AD 106, rejuvenated the (AD 98-117) Roman economy, and brought Trajan glory. His triumph (PUBLIC-6A513E) instigated 123 days of celebrations with Roman games that involved 10,000 gladiators and even more wild animals! Coins of Trajan are not uncommon.1 The PAS has over 3,200 examples (https://finds.org.uk/database/search/result s/ruler/256/objecttype/COIN/broadperiod/ ROMAN ) for Trajan alone, as well as much rarer examples of coins struck for his wife Plotina (2 examples), sister Marciana (5 examples), and niece Matidia (1 example). 1 The standard reference is RIC II. However, this has been superseded by the work of Bernhard Woytek, the leading expert on Trajanic coinage, in his Die Reichsprägung des Kaisers Traianus (98-117) (MIR 14, Vienna, 2010). -

Maecenas and the Stage

Papers of the British School at Rome 84 (2016), pp. 131–55 © British School at Rome doi:10.1017/S0068246216000040 MAECENAS AND THE STAGE by T.P. Wiseman Prompted by Chrystina Häuber’s seminal work on the eastern part of the mons Oppius, this article offers a radical reappraisal of the evidence for the ‘gardens of Maecenas’. Some very long-standing beliefs about the location and nature of the horti Maecenatiani are shown to be unfounded; on the other hand, close reading of an unjustly neglected text provides some new and unexpected evidence for what they were used for. The main focus of the argument is on the relevance of the horti to the development of Roman performance culture. It is intended to contribute to the understanding of Roman social history, and the method used is traditionally empirical: to collect and present whatever evidence is available, to define as precisely as possible what that evidence implies, and to formulate a hypothesis consistent with those implications. Sull’onda del fondamentale lavoro di Chrystina Häuber sul settore orientale del mons Oppius, questo articolo offre un completo riesame delle testimonianze relative ai ‘giardini di Mecenate’. Da un lato quest’operazione ha portato alla dimostrazione di come alcune convinzioni di lungo corso sulla localizzazione e natura degli horti Maecenatiani siano infondate; dall’altro lato, una lettura serrata di un testo ingiustamente trascurato fornisce alcune nuove e inaspettate prove delle modalità di utilizzo degli horti. Il principale focus della discussione risiede nella rilevanza degli horti allo sviluppo della cultura romana della performance. Con questo lavoro si vuole contribuire alla comprensione della storia sociale romana, e il metodo usato è quello, tradizionalmente, empirico: raccogliere e presentare tutte le fonti disponibili, definire nel modo più preciso possibile ciò che le fonti implicano e formulare un’ipotesi coerente con gli indizi rintracciati. -

Journal of Roman Archaeology

JOURNAL OF ROMAN ARCHAEOLOGY VOLUME 26 2013 * * REVIEW ARTICLES AND LONG REVIEWS AND BOOKS RECEIVED AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL Table of contents of fascicule 2 Reviews V. Kozlovskaya Pontic Studies 101 473 G. Bradley An unexpected and original approach to early Rome 478 V. Jolivet Villas? Romaines? Républicaines? 482 M. Lawall Towards a new social and economic history of the Hellenistic world 488 S. L. Dyson Questions about influence on Roman urbanism in the Middle Republic 498 R. Ling Hellenistic paintings in Italy and Sicily 500 L. A. Mazurek Reconsidering the role of Egyptianizing material culture 503 in Hellenistic and Roman Greece S. G. Bernard Politics and public construction in Republican Rome 513 D. Booms A group of villas around Tivoli, with questions about otium 519 and Republican construction techniques C. J. Smith The Latium of Athanasius Kircher 525 M. A. Tomei Note su Palatium di Filippo Coarelli 526 F. Sear A new monograph on the Theatre of Pompey 539 E. M. Steinby Necropoli vaticane — revisioni e novità 543 J. E. Packer The Atlante: Roma antica revealed 553 E. Papi Roma magna taberna: economia della produzione e distribuzione nell’Urbe 561 C. F. Noreña The socio-spatial embeddedness of Roman law 565 D. Nonnis & C. Pavolini Epigrafi in contesto: il caso di Ostia 575 C. Pavolini Porto e il suo territorio 589 S. J. R. Ellis The shops and workshops of Herculaneum 601 A. Wallace-Hadrill Trying to define and identify the Roman “middle classes” 605 T. A. J. McGinn Sorting out prostitution in Pompeii: the material remains, 610 terminology and the legal sources Y. -

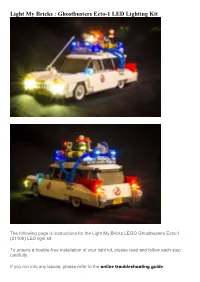

Light My Bricks : Ghostbusters Ecto-1 LED Lighting Kit

Light My Bricks : Ghostbusters Ecto-1 LED Lighting Kit The following page is instructions for the Light My Bricks LEGO Ghostbusters Ecto-1 (21108) LED light kit. To ensure a trouble-free installation of your light kit, please read and follow each step carefully. If you run into any issues, please refer to the online troubleshooting guide. Package contents: Package contents: 9x White 30cm Bit Light 9x Flashing White 30cm Bit Lights 2x 12-port Expansion boards 1x Flat Battery Pack (2x CR2032 Batteries included) 1x 5cm Connecting Cable Extra Lego pieces: 6x Lego 1×1 plates with clip (grey) 4x Lego 1×6 plates (white) 4x Lego 1×2 plates (grey) 4x Lego 1×2 plates (transparent blue) 1x Lego 1×1 round plate (transparent blue) Important things to note: Laying cables in between and underneath bricks Cables can fit in between and underneath LEGO® bricks, plates, and tiles providing they are laid correctly between the LEGO® studs. Do NOT forcefully join LEGO® together around cables; instead ensure they are laying comfortably in between each stud. CAUTION: Forcing LEGO® to connect over a cable can result in damaging the cable and light. Connecting cable connectors to Expansion Boards Take extra care when inserting connectors to ports of Expansion Boards. Connectors can be inserted only one way. With the expansion board facing up, look for the soldered “=” symbol on the left side of the port. The connector side with the wires exposed should be facing toward the soldered “=” symbol as you insert into the port. If a plug won’t fit easily into a port connector, do not force it. -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

The Roman Poets of the Augustan Age: Virgil by W

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Roman Poets of the Augustan Age: Virgil by W. Y. Sellar This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Roman Poets of the Augustan Age: Virgil Author: W. Y. Sellar Release Date: October 29, 2010 [Ebook 34163] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ROMAN POETS OF THE AUGUSTAN AGE: VIRGIL*** THE ROMAN POETS OF THE AUGUSTAN AGE: VIRGIL. BY W. Y. SELLAR, M.A., LL.D. LATE PROFESSOR OF HUMANITY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH AND FELLOW OF ORIEL COLLEGE, OXFORD iv The Roman Poets of the Augustan Age: Virgil THIRD EDITION OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMEN HOUSE, E.C. 4 London Edinburgh Glasgow New York Toronto Melbourne Capetown Bombay Calcutta Madras HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY vi The Roman Poets of the Augustan Age: Virgil IMPRESSION OF 1941 FIRST EDITION, 1877 THIRD EDITION, 1897 vii PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN TO E. L. LUSHINGTON, ESQ., D.C.L., LL.D., ETC. LATE PROFESSOR OF GREEK IN THE UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW. MY DEAR LUSHINGTON, Any old pupil of yours, in finishing a work either of classical scholarship or illustrative of ancient literature, must feel that he owes to you, probably more than to any one else, the impulse which directed him to these studies. -

Greek and Roman Mythology and Heroic Legend

G RE E K AN D ROMAN M YTH O LOGY AN D H E R O I C LE GEN D By E D I N P ROFES SOR H . ST U G Translated from th e German and edited b y A M D i . A D TT . L tt LI ONEL B RN E , , TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE S Y a l TUD of Greek religion needs no po ogy , and should This mus v n need no bush . all t feel who ha e looked upo the ns ns and n creatio of the art it i pired . But to purify stre gthen admiration by the higher light of knowledge is no work o f ea se . No truth is more vital than the seemi ng paradox whi c h - declares that Greek myths are not nature myths . The ape - is not further removed from the man than is the nature myth from the religious fancy of the Greeks as we meet them in s Greek is and hi tory . The myth the child of the devout lovely imagi nation o f the noble rac e that dwelt around the e e s n s s u s A ga an. Coar e fa ta ie of br ti h forefathers in their Northern homes softened beneath the southern sun into a pure and u and s godly bea ty, thus gave birth to the divine form of n Hellenic religio . M c an c u s m c an s Comparative ythology tea h uch . It hew how god s are born in the mind o f the savage and moulded c nn into his image . -

C HAPTER THREE Dissertation I on the Waters and Aqueducts Of

Aqueduct Hunting in the Seventeenth Century: Raffaele Fabretti's De aquis et aquaeductibus veteris Romae Harry B. Evans http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=17141, The University of Michigan Press C HAPTER THREE Dissertation I on the Waters and Aqueducts of Ancient Rome o the distinguished Giovanni Lucio of Trau, Raffaello Fabretti, son of T Gaspare, of Urbino, sends greetings. 1. introduction Thanks to your interest in my behalf, the things I wrote to you earlier about the aqueducts I observed around the Anio River do not at all dis- please me. You have in›uenced my diligence by your expressions of praise, both in your own name and in the names of your most learned friends (whom you also have in very large number). As a result, I feel that I am much more eager to pursue the investigation set forth on this subject; I would already have completed it had the abundance of waters from heaven not shown itself opposed to my own watery task. But you should not think that I have been completely idle: indeed, although I was not able to approach for a second time the sources of the Marcia and Claudia, at some distance from me, and not able therefore to follow up my ideas by surer rea- soning, not uselessly, perhaps, will I show you that I have been engaged in the more immediate neighborhood of that aqueduct introduced by Pope Sixtus and called the Acqua Felice from his own name before his ponti‹- 19 Aqueduct Hunting in the Seventeenth Century: Raffaele Fabretti's De aquis et aquaeductibus veteris Romae Harry B. -

Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy 2015-2016

EEXXTTRRAAOORRDDIINNAARRYY JJUUBBIILLEEEE ooff MMEERRCCYY The Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy 2015-2016 Pope Francis, who is moved by the human, social and cultural issues of our times, wished to give the City of Rome and the Universal Church a special and extraordinary Holy Year of Grace, Mercy and Peace. The “Misericordiae VulTus” Bull of indicTion The Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, which continues to be the programmatic outline for the pontificate of Pope Francis, offers a meaningful expression of the very essence of the Extraordinary Jubilee which was announced on 11 April 2015: “The Church has an endless desire to show mercy, the fruit of its own experience of the power of the Father’s infinite mercy” (EG 24). It is with this desire in mind that we should re-read the Bull of Indiction of the Jubilee, Misericordiae Vultus, in which Pope Fran- cis details the aims of the Holy Year. As we know, the two dates already marked out are 8 December 2015, the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception, the day of the opening of the Holy Door of St. Peter’s Basilica, and 20 November 2016, the Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe, which will conclude the Holy Year. Between these two dates a calendar of celebrations will see many different events take place. The Pope wants this Jubilee to be experienced in Rome as well as in local Churches; this brings partic- ular attention to the life of the individual Churches and their needs, so that initiatives are not just additions to the calendar but rather complementary. -

The Shops and Shopkeepers of Ancient Rome

CHARM 2015 Proceedings Marketing an Urban Identity: The Shops and Shopkeepers of Ancient Rome 135 Rhodora G. Vennarucci Lecturer of Classics, Department of World Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, University of Arkansas, U.S.A. Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to explore the development of fixed-point retailing in the city of ancient Rome between the 2nd c BCE and the 2nd/3rd c CE. Changes in the socio-economic environment during the 2nd c BCE caused the structure of Rome’s urban retail system to shift from one chiefly reliant on temporary markets and fairs to one typified by permanent shops. As shops came to dominate the architectural experience of Rome’s streetscapes, shopkeepers took advantage of the increased visibility by focusing their marketing strategies on their shop designs. Through this process, the shopkeeper and his shop actively contributed to urban placemaking and the distribution of an urban identity at Rome. Design/methodology/approach – This paper employs an interdisciplinary approach in its analysis, combining textual, archaeological, and art historical materials with comparative history and modern marketing theory. Research limitation/implications – Retailing in ancient Rome remains a neglected area of study on account of the traditional view among economic historians that the retail trades of pre-industrial societies were primitive and unsophisticated. This paper challenges traditional models of marketing history by establishing the shop as both the dominant method of urban distribution and the chief means for advertising at Rome. Keywords – Ancient Rome, Ostia, Shop Design, Advertising, Retail Change, Urban Identity Paper Type – Research Paper Introduction The permanent Roman shop was a locus for both commercial and social exchanges, and the shopkeeper acted as the mediator of these exchanges. -

Martial's and Juvenal's Attitudes Toward Women Lawrence Phillips Davis

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1973 Martial's and Juvenal's attitudes toward women Lawrence Phillips Davis Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Davis, Lawrence Phillips, "Martial's and Juvenal's attitudes toward women" (1973). Master's Theses. Paper 454. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARTIAL' S AND JUVENAL' S ATTITUDES TOWARD WOMEN BY LAWRENCE PHILLIPS DAVIS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF·ARTS IN ANCIENT LANGUAGES MAY 1973 APPROVAL SHEET of Thesis PREFACE The thesis offers a comparison between the views of Martial and Juvenal toward women based on selected .Epigrams of the former and Satire VI of the latter. Such a comparison allows the reader to place in perspective the attitudes of both authors in regard to the fairer sex and reveals at least a portion of the psychological inclination of both writers. The classification of the selected Epigrams ·and the se lected lines of Satire VI into categories of vice is arbi- . trary and personal. Subjective interpretation of vocabulary and content has dictated the limits and direction of the clas sification. References to scholarship regarding the rhetori cal, literary, and philosophic influences on Martial and Ju venal can be found in footnote6 following the chapter concern-· ~ng promiscuity.