Explicating the Dynamics of Gender Representation in the Practices of Headhunting and War of the Tangkhul Nagas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Consultancy Services for Preparation of Detailed Project Report DETAILED PROJECT REPORT for 2 Laning of Longpi Kajui-Razai/ Chingjaroi Khullen Road on NH 202 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 0.1 GENERAL National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) has decided to take up the development of various National Highways Corridors in the North-eastern state where the intensity of traffic has increased significantly in plain areas and where there is requirement of safe and efficient movement of traffic mainly in hilly terrains. This project is a part of the above mentioned programme and the project awarded to Consultant is Consultancy Services for carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre-construction services in respect of 2 laning of Yaingangpokpi-Nagaland Border in the state of Manipur. Project Stretch: Longpi Kajui-Razai/ Chingjaroi Khullen (25.448Km). The NHIDCL has been entrusted with implementation of the development of this corridor from Ministry’s Plan Funds. In order to fulfil the above task, NHIDCL has entrusted the work of preparation of the feasibility study and Detailed Project Report for the above project to M/s S. M. Consultants., vide contract agreement dated 19th January 2017. The Letter of Acceptance was communicated vide letter No NHIDCL/DPR/IM&UJ/Manipur/2016/293. 0.2 OBJECTIVE The main objectives of the consultancy service will focus on establishing technical, financial viability of the project and prepare detailed project reports for rehabilitation/ upgradation/ construction of the existing road to two lane NH with paved shoulder configuration with the following points to be ensured. -

Nature Worship

© IJCIRAS | ISSN (O) - 2581-5334 March 2019 | Vol. 1 Issue. 10 NATURE WORSHIP haobam bidyarani devi international girl's hostel, manipur university, imphal, india benevolent and malevolent spirits who had to be Abstract appeased through various forms of sacrifice. Nature Worship Haobam Bidyarani Devi, Ph.D. Student, Dpmt. Of History, Manipur University Keyword: Ancestors, Communities, Nature, Abstract: Manipur is a tiny state of the North East Offerings, Sacrifices, Souls, Spiritual, Supreme Being, region of India with its capital in the city of Imphal. Worshiped. About 90% of the land is mountainous. It is a state 1.INTRODUCTION inhabited by different communities. While the tribals are concentrated in the hill areas, the valley Manipur is a tiny state of the North East region of India of Imphal is predominantly inhabited by the Meiteis, with its capital in the city of Imphal. About 90% of the followed by the Meitei Pangals (Muslim), Non land is mountainous. It is a state inhabited by different Manipuris and a sizable proportion of the tribals. communities. While the tribals are concentrated in the During the reign of Garibniwaz in the late 18th hill areas, the valley of Imphal is predominantly century, the process of Sanskritisation occurred in inhabited by the Meiteis, followed by the Meitei Pangals the valley and the Meitei population converted en (Muslim), Non Manipuris and a sizable proportion of the masse to Hinduism. The present paper is primarily tribals. During the reign of Garibniwaz in the late 18th focused on Nature worship and animism, belief and century, the process of Sanskritisation occurred in the sacrifices performed by the various ethnic groups in valley and the Meitei population converted en masse to Manipur. -

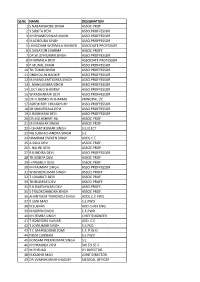

Slno Name Designation 1 S.Nabakishore Singh Assoc.Prof 2 Y.Sobita Devi Asso.Proffessor 3 Kh.Bhumeshwar Singh

SLNO NAME DESIGNATION 1 S.NABAKISHORE SINGH ASSOC.PROF 2 Y.SOBITA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 3 KH.BHUMESHWAR SINGH. ASSO.PROFFESSOR 4 N.ACHOUBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 5 LUNGCHIM WORMILA HUNGYO ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 6 K.SANATON SHARMA ASSOC.PROFF 7 DR.W.JOYKUMAR SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 8 N.NIRMALA DEVI ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 9 P.MUNAL SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 10 TH.TOMBI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 11 ONKHOLUN HAOKIP ASSO.PROFFESSOR 12 M.MANGLEMTOMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 13 L.MANGLEMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 14 LUCY JAJO SHIMRAY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 15 W.RADHARANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 16 DR.H.IBOMCHA SHARMA PRINCIPAL I/C 17 ASHOK ROY CHOUDHURY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 18 SH.SHANTIBALA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 19 K.RASHMANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 20 DR.MD.ASHRAF ALI ASSOC.PROF 21 M.MANIHAR SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 22 H.SHANTIKUMAR SINGH S.E,ELECT. 23 NG SUBHACHANDRA SINGH S.E. 24 NAMBAM DWIJEN SINGH ADDL.C.E. 25 A.SILLA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 26 L.NALINI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 27 R.K.INDIRA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 28 TH.SOBITA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 29 H.PREMILA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 30 KH.RAJMANI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 31 W.BINODKUMAR SINGH ASSCO.PROFF 32 T.LOKABATI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 33 TH.BINAPATI DEVI ASSCO.PROFF. 34 R.K.RAJESHWARI DEVI ASSO.PROFF., 35 S.TRILOKCHANDRA SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 36 AHANTHEM TOMCHOU SINGH ADDL.C.E.PWD 37 K.SANI MAO S.E.PWD 38 N.SUBHAS ADD.CHIEF ENG. 39 N.NOREN SINGH C.E,PWD 40 KH.TEMBA SINGH CHIEF ENGINEER 41 T.ROBINDRA KUMAR ADD. C.E. -

Statistical Year Book of Ukhrul District 2014

GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR STATISTICAL YEAR BOOK OF UKHRUL DISTRICT 2014 DISTRICT STATISTICAL OFFICE, UKHRUL DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR PREFACE The present issue of ‘Statistical Year Book of Ukhrul District, 2014’ is the 8th series of the publication earlier entitled „Statistical Abstract of Ukhrul District, 2007‟. It presents the latest available numerical information pertaining to various socio-economic aspects of Ukhrul District. Most of the data presented in this issue are collected from various Government Department/ Offices/Local bodies. The generous co-operation extended by different Departments/Offices/ Statutory bodies in furnishing the required data is gratefully acknowledged. The sincere efforts put in by Shri N. Hongva Shimray, District Statistical Officer and staffs who are directly and indirectly responsible in bringing out the publications are also acknowledged. Suggestions for improvement in the quality and coverage in its future issues of the publication are most welcome. Dated, Imphal Peijonna Kamei The 4th June, 2015 Director of Economics & Statistics Manipur. C O N T E N T S Table Page Item No. No. 1. GENERAL PARTICULARS OF UKHRUL DISTRICT 1 2. AREA AND POPULATION 2.1 Area and Density of Population of Manipur by Districts, 2011 Census. 1 2.2 Population of Manipur by Sector, Sex and Districts according to 2011 2 Census 2.3 District wise Sex Ratio of Manipur according to Population Censuses 2 2.4 Sub-Division-wise Population and Decadal Growth rate of Ukhrul 3 District 2.5 Population of Ukhrul District by Sex 3 2.6 Sub-Division-wise Population in the age group 0-6 of Ukhrul District by sex according to 2011 census 4 2.7 Number of Literates and Literacy Rate by Sex in Ukhrul District 4 2.8 Workers and Non-workers of Ukhrul District by sex, 2001 and 2011 5 censuses 3. -

PERFORMA for the QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT (Reporting Period from April to September, 2018)

National Mission on Himalayan Studies (NMHS) PERFORMA FOR THE QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT (Reporting Period from April to September, 2018) 1. Project Information Project ID NMHS/2017-18/MG26/10 Project Title Assessment, Documentation and Validation of Sustainable Traditional Management Practices with Special Emphasis on Carbon Sequestration and Livelihood Improvement in Eastern Himalaya Project Proponent Dr. Tuisem Shimrah Assistant Professor, Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University, Dwarka, Sector 16, New Delhi-110078 2. Objectives • To explore different traditional knowledge and characterize various traditional management practices in hill ecosystem; • To assess carbon sequestration potentials of various traditionally managed land uses; • To impart training and capacity building for traditional farming communities; • To preserve and enhance traditional knowledge to contribute to sustainable local livelihoods and sustainable use of forest biodiversity. 3. General Conditions • A report based on baseline data should be submitted by the project proponent in first quarter of the project and quantification of improvement in economic status of beneficiaries against baseline should be specified. • The project should be implemented specifically in the villages of the hilly region, not the valley region of the target state in consultation with the State government. • The Periodic Progress Report of the NMHS Project needs to be submitted and updated on the Online Portal of the NMHS (http://nmhsportal.org) by the PI/ Project Proponent on Quarterly basis consistently. Monitoring indicators for the project should be able to quantify the difference made on ground. • A Certificate should be provided that this work is not the repeat of earlier work (as a mandatory exercise). • The roles and responsibilities of each implementing partners should be delineated properly with their budget. -

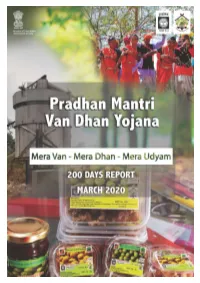

200 DAYS FINAL Print

200 days of PMVDY – March 2020 1 1 200 days of PMVDY – March 2020 VanDhan is a movement spread across 27 States The Editorial Board EDITOR- IN- CHIEF - Shri. Pravir Krishna ,Managing Director, TRIFED 1. Sh. Amit Bhatnagar , DGM – MFP, TRIFED 2. Sh. Sandeep Pahalwan, SM – MFP, TRIFED 3. Sh. Roy Mathew, PMU Lead, TRIFED 4. Sh. Om Prakash - AM,MFP, TRIFED 5. Sh. Nikhil Rathi ,PMU,TRIFED 6. Sh. Javed Akhtar, Consultant Designer, TRIFED 7. Sh. Abhishek Toppo, Van Dhan Intern, TRIFED 8. Ms. Nutan Rani , Van Dhan Intern, TRIFED 9. Ms. Vanika Bajaj, Van Dhan Intern, TRIFED 10. Ms. Haleema Sadaf, Van Dhan Intern, TRIFED *The Van Dhan Natural producs on the cover page of this report have been produced at VDVK Senapati, Manipur. *The distillation unit shown on the cover page of this report has been installed at Dimapur. Nagaland 2 200 days of PMVDY – March 2020 Contents Content Page No. *States Page No. Messages 4 Andhra Pradesh 45 Van Dhan Timeline 7 Arunachal Pradesh 63 MSP for MFP Scheme 8 Assam 47 Implementation at a Glance 9 Bihar 60 About PMVDY 10 Van Dhan Products 13 Chhattisgarh 51 Good Manufacturing Goa 65 Practice & 14 Quality Certifications Gujarat 56 Van Dhan Equipments 15 Himachal Pradesh 62 Equipment & Toolkits 16 J&K, Ladakh 64 Premises for Processing & 17 Storage Jharkhand 41 PMVDY -Stages 19 Karnataka 37 State Advocacy Workshops 20 Kerala 55 District Advocacy 22 Workshops Madhya Pradesh 59 VDVK Trainings and 23 Advocacy Workshops Maharashtra 39 Convergences 24 Manipur 33 R&D support to VanDhan 25 Meghalaya 63 TRIFOOD 26 Mizoram 61 Tech For Tribals 27 Nagaland 35 CSR supported Van Dhan 29 Programs Odisha 49 Industry Partnerships 30 Rajasthan 43 Web application features 31 Sikkim 60 Model VDVKs 32 Tamil Nadu 58 States* 33-65 Telangana 61 Risk Assessment, Monitorng 65 & Evaluation Tripura 57 Corporate Affairs Division 66 Uttar Pradesh 53 Rs. -

December 22 Page 2

Imphal Times Supplementary issue 2 Editorial The Cave Born Tribes of Manipur and Tangkhul Literature O, tui hi lânijilo Reached the Manipur valley groups left some signs for the next By: Dr. H. Shimreingam Imphal, Tuesday, December 22, 2015 Lâ hi tuinijilo, O opened the packed rice (and shared) group/s, but many went to some other Asst. Professor, Dept. of English Âyârningkathemvayo! O shouted at Shokvao direction and the groups could not William Pettigrew College, Ukhrul O, sâkazaklo, O cross the ocean my son Ashang come together in one place. So the Itholipeidaphokrâlo O distributed fire at Meizailung phrase ‘Dardouy Lam-mong’ Poireiton journeyed along the Selection blues (C. Chiphang) O HunphunPatriach (Dardouy losing track), the first southern Tangkhul, Maring and Anal The process of selecting the best for a particular task has Free Translation in English O you LongpiKajui and Ronra… known track of the Dardouy was areas as they were his kinsmen.)The O, say word is song, O Marem and Kalhang (villages) reaching Burma and came to people who moved out of this place been an inherent process of nature itself, from which man, O say song is word (History), O reaching ThisomTusomrara. KulkungKuirel and Inching valley lovingly murmured Leishi, Leishi with the passage of time polished and refined it to become O Western educated girl! From the above Tangkhul folksong (Ningthi river) then reached (meaning love in Tangkhul), so the what is known as a formal selection process. At present, the O, sing merrily, when the Tangkhuls passed through Angkoching and then reached Samsok, village was called Leishi. -

1 District Census Handbook-Ukhrul

DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK-UKHRUL 1 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK-UKHRUL 2 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK-UKHRUL G A MANIPUR A To Meluri L UKHRUL DISTRICT From Kohima NH 202 5 0 5 10 N SH A Kilometres T From Mao N r e v i SH R a D g C r a r e g e v n v i i i R R R k o L i in u I a L m m a R h C UKHRUL NORTH R From Mao SUB-DIVISION Ukhrul District has 6 C.D./T.D. Blocks. Chingai T.D. Block is co-terminus with Ukhrul North Sub-Division. CHINGAI Ukhrul Central Sub-Division has 2 T.D. Blocks as Ukhrul and Bungchong Meiphei but their boundary R is not yet define as non survey. Kamjong T.D. Block T is co-terminus with Kamjong Chassad Sub-Division. r River Phungyar T.D. Block is co-terminus with Phungyar e g iv n Phaisat Sub-Division. Kasom Khullen T.D. Block is R a d k g co-terminus with Ukhrul South Sub-Division. o n L a g L From Tadubi n S o kh A A District headquarters is also sub-division headquarters. From Purul I D ! r UKHRUL CENTRAL e iv UKHRUL (CT) R il r SUB-DIVISION Ir e v G i R UKHRUL P M k o 6 L I g N ! D I I A n a h I HUNDUNG Area (in Sq. Km.)................ 4544 SH Number of Sub-Divisions.... 5 r e Number of Census Town. -

Ecology and Human Well-Being

Ecology and Human Well-Being Ecology and Human Well-Being Edited by Pushpam Kumar B. Sudhakara Reddy Copyright © The Indian Society for Ecological Economics, 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2007 by Sage Publications India Pvt Ltd B1/I1, Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area Mathura Road New Delhi 110 044 www.sagepub.in Sage Publications Inc 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320 Sage Publications Ltd 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP Sage Publications Asia-Pacifi c Pte Ltd 33 Pekin Street #02-01 Far East Square Singapore 048763 Published by Vivek Mehra for Sage Publications India Pvt Ltd, typeset in 10/12 pt Book Antiqua by Star Compugraphics Private Limited, Delhi and printed at Chaman Enterprises, New Delhi. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ecology and human well-being / edited By Pushpam Kumar, B. Sudhakara Reddy. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Human ecology—India. 2. Human ecology—Economic aspects—India. 3. Social ecology—Economic aspects—India. 4. Well-being—India. 5. Quality of life—India. 6. India—Social conditions. 7. India— Economic conditions. I. Kumar, Pushpam. II. Sudhakara Reddy, B. GF661.E25 304.20954—dc22 2007 2007020323 ISBN: 978–0–7619–3553–7 (HB) 978–81–7829–712–5 (India–HB) The Sage Team: Sugata Ghosh and Janaki Srinivasan Contents List of Tables viii List of Figures xii List of Abbreviations xv Preface xviii Introduction by Pushpam Kumar and B. -

Chapter Vii Settlement and Subsistence Patterns

CHAPTER VII SETTLEMENT AND SUBSISTENCE PATTERNS CHAPTER VII SETTLEMENT PATTERNS AND SUBSISTENCE 7.1. SETTLEMENT PATTERN Chang (1958: 229) differentiates settlement pattern into two types: (i) Settlement pattern, strictly defined, means the manner in which human settlements are arranged over the landscape in relation to physiography and environment; and (ii) it is the manner in which the inhabitants arranged their various structures within the community and the way the communities are arranged in the 'aggregate' which means a gathering of certain number of communities bound by social, political, military, commercial or religious times. There are many definitions for settlement patterns given by Willey (1953: 155) and so on. Here Sanders' (1956: 105) definition will serve our purpose. According to him "the study of settlement patterns is a study of the ecological and demographic aspects of culture." He equates settlement patterns with human ecology since it is concerned with the distribution of population over the landscape and investigation of the reasons behind their distribution. Studies made so far indicate that all human activities assumed an orderly arrangement in space and they tended to arrange themselves about given points. Hauley (1950: 236-237) traces the reasons of this fact to three fundamental life conditions, namely, interdependence among the individuals, dependence of activities or functions on various characteristics of land, and friction of space. The first two accounts for the tendency for a pattern to develop, while the third affects the size and specific shape the pattern assumes. The first condition exercises an attractive force and leads to concentration of settlements while the second exerts a disruptive influence and 178 leads to distribution of men and their activities. -

NAGALAND and Th. Muivah's Terrorist Activities

NAGALAND AND Th. Muivah’s terrorist Activities By W. Shapwon 1 Copy right © 2005 by: W. Shapwon Heimi All rights reserved. First edition in August 2005. Printed 3000 copies. Revised and added more terror acts of NSCN-IM from 2005 to 2010 with some photos in 2010 2 PREFACE I am constrained to write this book so as to let our people know what had gone wrong in the running history of the Naga nation. It is an undeniable historical fact that if Thuingaleng Muivah and Isak Chishi Swu, the then (1980) General Secretary of the Naga National Council and Finance Minister of the Federal Government of Nagaland had not deviated from the Naga national stand and policy, no fratricidal killing would be taken place in the history of the Naga nation. However, Th. Muivah and Isak had fallaciously portrayed that they have saved the Naga nation from doom by forming the so-called National Socialist Council of Nagaland in 1980. They also projected that the bloody partition took place among the Nagas was because of the NNC and FGN betrayed the Naga nation by signing the Shillong Accord in 1975. Believing their words, some Naga NGO leaders and some Church leaders have given their fullest support to Isak and Muivah thinking that they had taken the right step and saved Nagaland. And so, following Th. Muivah’s false allegation on the NNC and FGN they have been stating that: “The NNC/FGN signed the infamous Shillong Accord and thereby divided the Naga political movement.” “The NNC/FGN based at the Kohima Transit Peace Camp has caused needless damage to the NNC and Naga unity.” “The Shillong Accord or the NNC is the most damaging factor of the Naga Nation”, etc.