Chapter Vii Settlement and Subsistence Patterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur

A STUDY ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION OF TANGKHUL COMMUNITY IN UKHRUL DISTRICT, MANIPUR. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIAL WORK UNDER THE BOARD OF SOCIAL WORK STUDIES BY DEPEND KAZINGMEI PRN. 15514002238 UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. G. R. RATHOD DIRECTOR, SOCIAL SCIENCE CENTRE, BVDU, PUNE SEPTEMBER 2019 DECLARATION I, DEPEND KAZINGMEI, declare that the Ph.D thesis entitled “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur.” is the original research work carried by me under the guidance of Dr. G.R. Rathod, Director of Social Science Centre, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune, for the award of Ph.D degree in Social Work of the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. I hereby declare that the said research work has not submitted previously for the award of any Degree or Diploma in any other University or Examination body in India or abroad. Place: Pune Mr. Depend Kazingmei Date: Research Student i CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur”, which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Ph.D in Social Work of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Depend Kazingmei under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body. -

LIST of FARMERS District : Ukhrul Block : Ukhrul

LIST OF FARMERS District : Ukhrul Block : Ukhrul Card No. Farmer's Name Village/ Block District State Pin no. 447 R. Pamlei Teinem Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 449 Ramreishang Vashi Teinem Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 451 K. Tabitha Ukhrul Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 452 Wisdom Luiyainaotang Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 456 Khaiwonla Kasomtang Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 458 Simlarose Meizailung Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 460 L.S. Wungthing Meizailungtang Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 551 A.S. Ningreingam T.Shimin Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 552 A.S. Ngaranmi T.Shimin Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 554 A.S. Thotsem T.Shimin Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 563 A.S. Holy T.Shimin Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 570 A.S. Wonreithing T.Shimin Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 585 A.S. Rock Tashar Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 588 A.S. Shangchuila Tushen Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 589 A.S. Ngamthing Tashar Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 595 A.S. Khaso Tushen Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 598 A.S. Ramshing Tashar Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 404 R.S. Methew longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 405 Chihanpam longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 406 Yursem Awungshi longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 407 S Sareng longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 408 Leishiwon longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 409 L. Shangam longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 410 Joshep Tallanao longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 411 Paoyaola longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 412 Obed Luiram longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 413 T. Yangmi longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 445 K. Horchipei Sirarakhong Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 446 R. -

SLBC MEETING for the QUARTER ENDED MARCH, 2019 for MANIPUR HELD on 8Th JULY, 2019 at the CONFERENCE HALL, MANIPUR SECRETARIAT, IMPHAL

MINUTES OF THE 58th SLBC MEETING FOR THE QUARTER ENDED MARCH, 2019 FOR MANIPUR HELD ON 8th JULY, 2019 AT THE CONFERENCE HALL, MANIPUR SECRETARIAT, IMPHAL The SLBC meeting for the quarter ended March, 2019 was held on the 8th July, 2019 at the Conference Hall, Manipur Secretariat, Imphal. The meeting was chaired by Dr. J. Suresh Babu, the Chief Secretary, Govt. of Manipur & co-chaired by Shri. Sunil Kumar Tandon, Chief General Manager, State Bank of India, North East Circle, Guwahati and attended by Shri Rakesh Ranjan, Principal Secretary, Finance, Shri. E.Priyokumar Singh, IGP (AP/OP& Prev), Smt. Anna Arambam, Director/ Institutional Finance (DIF), Ms. Mary Tangpua, GM, RBI, Dr. KJ Satyasai, GM, NABARD, senior officials of the State Government, DCs/ADCs of the districts and senior officials from different Banks. Shri. Lalkholun Hangshing, SLBC Convener, Manipur opened the meeting by welcoming all the dignitaries, members and participants present in the conference hall. I. Adoption of the Minutes of the last SLBC meeting: The SLBC Convener informed the house that minutes of last SLBC meeting held on 08.05.2019 was approved by the Chairman and accordingly, circulated to all members. However, there was a request by RBI for amendment in point numbers 3.4, 3.10, 5.2, 5.3 and 6.1, which he said has already been incorporated in the revised minutes. With no objections to the revised minutes from any of the members, the House adopted the same. II. Discussion on Action Taken Report (ATR) of the Dec’18 quarter SLBC Meeting and Discussion thereon: 1. -

Manipur State Information Technology Society

MANIPUR STATE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY SOCIETY (A Government of Manipur Undertaking) 4th Floor, Western Block, New Secretariat, Imphal – 795001 www.msits.gov.in; Email: [email protected] Phone: 0385-24476877 District wise Status of Common Service Centres (As on 25th March, 2013) District: Ukhrul Total No. of CSCs : 33 VSAT Solar Power Sl. CSC Location & VLE Contact District BLOCK CSC Name Name of VLE Installation pack status No Address Number Status 1 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Hundung Hundung K.Y.S Yangmi 9612005006 Installed Installed 2 Ukhrul Chingai CSC-Kalhang Kalhang R.S. Michael (Aphung) 9612765614 / Pending Installed 9612130987 3 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Nungshong Nungshong Khullen Ignitius Yaoreiwung 9862883374 Pending Installed Khullen Chithang 4 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Shangkai Shangkai Chongam Haokip 9612696292 Installed Installed 5 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-New Cannon New Cannon ZS Somila 9862826487 / Installed Installed 9862979109 6 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Jessami Jessami Village Nipekhwe Lohe 9862835841 Pending Installed 7 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Teinem Teinem Mashangam Raleng 8730963043 Pending Installed 8 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Seikhor Seikhor L.A. Pamreiphi 9436243204 / Pending Installed 857855919 / 8731929981 9 Ukhrul Chingai CSC-Chingjaroi Chingjaroi Khullen Joyson Tamang 9862992294 Pending Installed Khullen 10 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Litan Litan JS. Aring 9612937524 / Installed Installed 8974425854 / 9436042452 11 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Shangshak Shangshak khullen R.S. Ngaranmi 9862069769 / Pending Installed T.D.Block Khullen 9436086067 / 9862701697 12 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Lambui Lambui L. Seth 9612489203 / Installed Installed T.D.Block 8974459592 / 9862038398 13 Ukhrul Kasom Khullen CSC-Kasom Kasom Khullen Shanglai Thangmeichui 9862760611 / Not approved for Installed T.D.Block Khullen 9612320431 VSAT 14 Ukhrul Kasom Khullen CSC-Khamlang Khamlang N. -

'Collective Memory' As an Alternative to Dominant (Hi)Stories In

NATASA THOUDAM: ‘Collective Memory’ as an Alternative to Dominant (Hi)stories in Narratives by Women from and in Manipur Postcolonial Interventions, Vol. II, Issue 1 Postcolonial Interventions, Vol. II, Issue 1, (ISSN 2455-6564) Abstract Theorizing in the context of France, Pierre Nora laments the erosion of ‗national memory‘ or what he calls ―milieux de memoire‖ and the emergence of what have remained of such an erosion as ‗sites of memory‘ or ―lieux de memoire‖ (7–24). Further he contends that all historic sites or ―lieux d’histoire‖ (19) such as ―museums, archives, cemeteries, festivals, anniversaries, treaties, depositions, monuments, sanctuaries, fraternal orders‖ (10) and even the ―historian‖ can become lieux de memoire provided that in their invocation there is a will to remember (19). In contrast to Nora‘s lamentation, in the particular context of Manipur, a state in Northeast part of India, there is a reversal. It is these very ‗sites of memory‘ that bring to life the ‗collective memory‘ of Manipur, which is often national, against the homogenizing tendencies of the histories of conflicting nationalisms in Manipur, including those of the Indian nation-state. This paper shows how photographs of Manorama Thangjam‘s ‗raped‘ body, the suicide note of the ‗raped‘ Miss Rose, Mary Kom‘s autobiography, and ‗Rani‘ Gaidinlui‘s struggle become sites for ‗collective‘ memory that emerge as an alternative to history in Manipur. Keywords: Manipuri Women Writers, Pierre Nora, Conflict of Nationalisms, Collective Memory, Sites of Memory 34 Postcolonial Interventions, Vol. II, Issue 1, (ISSN 2455-6564) Theorizing in the context of France, Pierre Nora laments the erosion of ‗national memory‘ or what he calls ―milieux de memoire‖ and the emergence of what have remained of such an erosion as ‗sites of memory‘ or ―lieux de memoire‖ (7–24). -

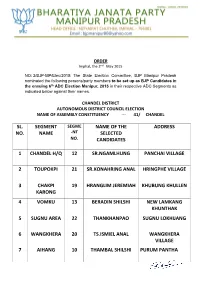

Sl. No. Segment Name Name of the Selected Candidates

ORDER Imphal, the 2nd May 2015 NO: 2/BJP-MP/Elec/2015: The State Election Committee, BJP Manipur Pradesh nominated the following persons/party members to be set up as BJP Candidates in the ensuing 6th ADC Election Manipur, 2015 in their respective ADC Segments as indicated below against their names. CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 41/ CHANDEL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 CHANDEL H/Q 12 SR.NGAMLHUNG PANCHAI VILLAGE 2 TOUPOKPI 21 SR.KONAHRING ANAL HRINGPHE VILLAGE 3 CHAKPI 19 HRANGLIM JEREMIAH KHUBUNG KHULLEN KARONG 4 VOMKU 13 BERADIN SHILSHI NEW LAMKANG KHUNTHAK 5 SUGNU AREA 22 THANKHANPAO SUGNU LOKHIJANG 6 WANGKHERA 20 TS.ISMIEL ANAL WANGKHERA VILLAGE 7 AIHANG 10 THAMBAL SHILSHI PURUM PANTHA 8 PANTHA 11 H.ANGTIN MONSANG JAPHOU VILLAGE 9 SAJIK TAMPAK 23 THANGSUANKAP GELNGAI VILAAGE 10 TOLBUNG 24 THANGKHOMANG AIBOL JOUPI VILLAGE HAOKIP CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 42/ TENGNOUPAL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 KOMLATHABI 8 NG.KOSHING MAYON KOMLATHABI VILLAGE 2 MACHI 2 SK.KOTHIL MACHI VILLAGE, MACHI BLOCK 3 RILRAM 5 K.PRAKASH LANGKHONGCHING VILLAGE 4 MOREH 17 LAMTHANG HAOKIP UKHRUL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 43/ PHUNGYAR SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 GRIHANG 19 SAUL DUIDAND GRIHANG VILLAGE KAMJONG 2 SHINGKAP 21 HENRY W. KEISHING TANGKHUL HUNDUNG 3 KAMJONG 18 C.HOPINGSON KAMJONG BUNGPA KHULLEN 4 CHAITRIC 17 KS.GRACESON SOMI PUSHING VILLAGE 5 PHUNGYAR 20 A. -

A Tribal Identity: the Traditional Costume

Multi-Disciplinary Journal ISSN No- 2581-9879 (Online), 0076-2571 (Print) www.mahratta.org, [email protected] A TRIBAL IDENTITY: THE TRADITIONAL COSTUME A.S. Varekan1 Research Scholar (Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth) , Professor, Department of Economics Spicer Adventist University A.S. Ellen2 Research Scholar (William Carey University), Assistant Professor, Department of Education Spicer Adventist University Abstract: This articles outlines the unique traditional costumes of the Tangkhul tribe. A tribal community that occupies the Ukhrul district of Manipur and Somrah track of Myanmar. Their arrival in the present habitat is shrouded in mystery as there is no written record up until the arrival of Rev. William Pettigrew. They have very rich culture and traditions and one element of it is the beautiful shawls and skirts weaved in the domestic handloom. Handloom industry is one of the oldest industry of this tribe, an industry that have survived the test of times. The tribe is known for the numerous handloom products and each item having cultural meaning and significance. It is a paper that strives to present the importance of preserving these costumes to protect the tribe from extinction and being suck into the ever dynamics of social, political and economic world. Terms: Kashan, Kachon, La Kharan, Kachon kharak, Leingapha, Introduction: Manipur is a small Northeastern state of India. It is small in physical landmass but rich in cultural diversity. The valley and the surrounding Himalayan hills is inhabited by numerous tribes and communities. It is mini India in terms of diversity of dialects, traditions and religion that co-exist in conflicts or in symbiosis. -

Manipur Floods, 2015

Joint Needs Assessment Report on Manipur Floods, 2015 Joint Needs Assessment Report This report contains the compilation of the JNA –Phase 01 actions in the state of Manipur, India in the aftermath of the incessant rains and the subsequent embankment breaches which caused massive floods in first week of August 2015 affecting 6 districts of people in valley and hills in Manipur. This is the worst flood the state has witnessed in the past 200 years as observed on traditional experiences. Joint Needs Assessment Report: Manipur Floods 2014 Disclaimer: The interpretations, data, views and opinions expressed in this report are collected from Inter-agency field assessments Under Joint Need assessment (JNA) Process, District Administration, individual aid agencies assessments and from media sources are being presented in the Document. It does not necessarily carry the views and opinion of individual aid agencies, NGOs or Sphere India platform (Coalition of humanitarian organisations in India) directly or indirectly. Note: The report may be quoted, in part or full, by individuals or organisations for academic or Advocacy and capacity building purposes with due acknowledgements. The material in this Document should not be relied upon as a substitute for specialized, legal or professional advice. In connection with any particular matter. The material in this document should not be construed as legal advice and the user is solely responsible for any use or application of the material in this document. Page 1 of 27 | 25th August 2014 Joint Needs Assessment Report: Manipur Floods 2014 Contents 1 Executive Summary 4 2 Background 5 3 Relief Measures GO & NGO 6 4 Inherent capacities- traditional knowledge 6 5 Field Assessment: 7 6 Sector wise needs emerging 7 6.1 Food Security and Livelihoods 7 a. -

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

NEWSLETTER NEFOR FREE PUBLIC CIRCULATION Vol

NEWSLETTER NEFOR FREE PUBLIC CIRCULATION Vol. XIII. No. 10, October, 2011 MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS GOVERNMENT OF INDIA A Monthly Newsletter on the North Eastern Region of India Also available on Internet at : htpp:mha.nic.in We must be the change we wish to see. Mahatma Gandhi DEVELOPMENTS WITH REFERENCE TO C O N T E N T S NORTH EASTERN REGION DEVELOPMENTS WITH REFERENCE TO NORTH 1. A review committee meeting on monitoring of EASTERN REGION ceasefire with NSCN/K was held on October 10, ACTIVITIES CARRIED OUT UNDER CIVIC ACTION 2011. PROGRAMME BY CENTRAL ARMED POLICE FORCES 2. On October 13-14, 2011 tripartite talks were held with DHD/N and DHD/J for finalization of Memorandum of PROGRAMMES UNDERTAKEN BY MINISTRY OF I&B Settlement. IN THE NORTH EASTERN REGION 3. On October 15, 2011, a meeting was held between MANIREDA LIGHTING UP MANIPUR MHA and Chief of General Staff of Myanmar Army to SELF-HELP GROUPS TRANSFORMING LIVES IN discuss security related issues. ASSAM 4. A tripartite meeting involving the representatives of Government of Assam and ULFA was held on NABAKISHORE SINGH, MANIPUR’S RISING STAR 25.10.2011 under the Chairmanship of Union Home IMPLEMENTATION OF NRCP WORKS IN THE STATE Secretary (Shri R.K Singh) at New Delhi to discuss OF SIKKIM demands submitted by ULFA on 05.08.2011 to Union Home Minister. WATER QUALITY TESTING LABORATORY Representatives of ULFA were headed by Shri Arabinda ESTABLISHED IN SIKKIM Rajkhowa (Chairman, ULFA). Chief Secretary, SIKKIM, GOA AND DELHI RANKED NO. 1 IN STATE Government of Assam (Sh. -

Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Consultancy Services for Preparation of Detailed Project Report DETAILED PROJECT REPORT for 2 Laning of Longpi Kajui-Razai/ Chingjaroi Khullen Road on NH 202 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 0.1 GENERAL National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) has decided to take up the development of various National Highways Corridors in the North-eastern state where the intensity of traffic has increased significantly in plain areas and where there is requirement of safe and efficient movement of traffic mainly in hilly terrains. This project is a part of the above mentioned programme and the project awarded to Consultant is Consultancy Services for carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre-construction services in respect of 2 laning of Yaingangpokpi-Nagaland Border in the state of Manipur. Project Stretch: Longpi Kajui-Razai/ Chingjaroi Khullen (25.448Km). The NHIDCL has been entrusted with implementation of the development of this corridor from Ministry’s Plan Funds. In order to fulfil the above task, NHIDCL has entrusted the work of preparation of the feasibility study and Detailed Project Report for the above project to M/s S. M. Consultants., vide contract agreement dated 19th January 2017. The Letter of Acceptance was communicated vide letter No NHIDCL/DPR/IM&UJ/Manipur/2016/293. 0.2 OBJECTIVE The main objectives of the consultancy service will focus on establishing technical, financial viability of the project and prepare detailed project reports for rehabilitation/ upgradation/ construction of the existing road to two lane NH with paved shoulder configuration with the following points to be ensured. -

GOVT. SCHOOLS Type of School Rural/ Sl

LIST OF SCHOOLS ( As on 30th September, 2015 ) GOVT. SCHOOLS Type of School Rural/ Sl. Class Managemen Name of School Boys/ Address Urban Constituency Block Remarks No. Structure t Girls/ (R/U) Co-Edn 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 HIGHER SECONDARY Schools in CPIS ( ZEO - Bishnupur ) 1 Bishnupur Higher Secondary School VI-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Bishnupur Ward No.6 Urban Bishnupur BM Bishnupur Hr./Sec Nambol Hr./Sec, Nambol 2 Nambolg Higherp Secondary p School IX-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Nambol Ward No. 3 Urban Nambol NM 3 Higher Secondary School IX-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Moirang Lamkhai Urban Moirang MM Moirang Multipurpose Hr./Sec Schools in CPIS ZEO Imphal- East 1 Ananda Singh Hr.Sec. School IX-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. khumunnom Urban Wangkhei IMC Ananda Singh Hr./Sec Academy 2 Churachand Hr.Sec. School IX-XII Edn Dept Boys Palace Gate Urban Yaiskul IMC C.C. Higher Sec. School 3 Lamlong Hr.Sec. School VI-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Khurai Thoudam Lk. Urban Wangkhei IMC Lamlong Hr./Sec 4 Azad Hr.Sec. School VI-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Yairipok Tulihal Rural Andro I- E -II Azad High School, Yairipok 5 Sagolmang Hr.Sec. School VI-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Sagolmang Rural Khundrakpam I- E -I Sagolmang Govt. H/S. ( ZEO-Jiribam) 1 Jiribam Higher Secondary IX-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Babupara Jiribam Urban Jiribam JM Jiribam Hr./Sec 2 Borobekara Hr.Sec. III-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Borobekara Rural Jiribam Jiribam Borobekra Hr.