Chilean Jagged Lobster, Projasus Bahamondei, in the Southeastern Pacific Ocean: Current State of Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Classification of Living and Fossil Genera of Decapod Crustaceans

RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2009 Supplement No. 21: 1–109 Date of Publication: 15 Sep.2009 © National University of Singapore A CLASSIFICATION OF LIVING AND FOSSIL GENERA OF DECAPOD CRUSTACEANS Sammy De Grave1, N. Dean Pentcheff 2, Shane T. Ahyong3, Tin-Yam Chan4, Keith A. Crandall5, Peter C. Dworschak6, Darryl L. Felder7, Rodney M. Feldmann8, Charles H. J. M. Fransen9, Laura Y. D. Goulding1, Rafael Lemaitre10, Martyn E. Y. Low11, Joel W. Martin2, Peter K. L. Ng11, Carrie E. Schweitzer12, S. H. Tan11, Dale Tshudy13, Regina Wetzer2 1Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PW, United Kingdom [email protected] [email protected] 2Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90007 United States of America [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3Marine Biodiversity and Biosecurity, NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Kilbirnie Wellington, New Zealand [email protected] 4Institute of Marine Biology, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung 20224, Taiwan, Republic of China [email protected] 5Department of Biology and Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602 United States of America [email protected] 6Dritte Zoologische Abteilung, Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien, Austria [email protected] 7Department of Biology, University of Louisiana, Lafayette, LA 70504 United States of America [email protected] 8Department of Geology, Kent State University, Kent, OH 44242 United States of America [email protected] 9Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum, P. O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands [email protected] 10Invertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, 10th and Constitution Avenue, Washington, DC 20560 United States of America [email protected] 11Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 12Department of Geology, Kent State University Stark Campus, 6000 Frank Ave. -

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade AUSTIN B. WILLIAMS Introduction tons to pounds to conform with US. tinents and islands, shoal platforms, and fishery statistics). This total includes certain seamounts (Fig. 1 and 2). More Lobsters are valued throughout the clawed lobsters, spiny and flat lobsters, over, the world distribution of these world as prime seafood items wherever and squat lobsters or langostinos (Tables animals can also be divided rougWy into they are caught, sold, or consumed. 1 and 2). temperate, subtropical, and tropical Basically, three kinds are marketed for Fisheries for these animals are de temperature zones. From such partition food, the clawed lobsters (superfamily cidedly concentrated in certain areas of ing, the following facts regarding lob Nephropoidea), the squat lobsters the world because of species distribu ster fisheries emerge. (family Galatheidae), and the spiny or tion, and this can be recognized by Clawed lobster fisheries (superfamily nonclawed lobsters (superfamily noting regional and species catches. The Nephropoidea) are concentrated in the Palinuroidea) . Food and Agriculture Organization of temperate North Atlantic region, al The US. market in clawed lobsters is the United Nations (FAO) has divided though there is minor fishing for them dominated by whole living American the world into 27 major fishing areas for in cooler waters at the edge of the con lobsters, Homarus americanus, caught the purpose of reporting fishery statis tinental platform in the Gul f of Mexico, off the northeastern United States and tics. Nineteen of these are marine fish Caribbean Sea (Roe, 1966), western southeastern Canada, but certain ing areas, but lobster distribution is South Atlantic along the coast of Brazil, smaller species of clawed lobsters from restricted to only 14 of them, i.e. -

Distribución Y Abundancia De Larvas De Langostino Colorado Pleuroncodes Monodon Frente a La Costa De Concepción, Chile

Invest. Mar., Valparaíso, 22: 13-29, 1994 Distribución de larvas de langostino colorado 13 Distribución y abundancia de larvas de langostino colorado Pleuroncodes monodon frente a la costa de Concepción, Chile SERGIO PALMA G. Escuela de Ciencias del Mar Universidad Católica de Valparaíso Casilla 1020, Valparaíso, Chile RESUMEN. Se analiza la distribución y abundancia de larvas de langostino colorado Pleuroncodes monodon captura- das en cuatro cruceros oceanográficos efectuados entre abril y diciembre de 1991, frente a la costa de Concepción, Chile. Las muestras de zooplancton se obtuvieron en 15 estaciones oceanográficas, mediante pescas oblicuas con redes Bongo desde el fondo a superficie, con un máximo de 200 m de profundidad. En todos los cruceros realizados se observó la presencia de larvas de langostino, encontrándose la mayor abundancia en noviembre. Las mayores densidades de larvas se detectaron en aguas sobre la plataforma continental, particularmente en el norte del área de estudio. La biomasa zooplanctónica alcanzó valores máximos en abril y mínimos en junio, registrándose las mayores densidades en aguas de la plataforma, en el norte y sur del área de estudio. La distribución temporal de los distintos estados de desarrollo (zoeas y postlarvas), sugiere el desplazamiento desde la costa hacia el talud, a medida que avanza la metamorfosis larval. La distribución vertical de las larvas mostró una preferencia de los estados de zoea por el estrato 0-25 m, mientras que las postlarvas se concentraron en el estrato 25-50 m. Bajo 50 m de profundidad, se observó una escasa cantidad de individuos. Palabras claves: Pleuroncodes monodon, larvas langostino colorado, biomasa zooplancton, distribución espacio-temporal, abundancia. -

Wild Species 2010 the GENERAL STATUS of SPECIES in CANADA

Wild Species 2010 THE GENERAL STATUS OF SPECIES IN CANADA Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council National General Status Working Group This report is a product from the collaboration of all provincial and territorial governments in Canada, and of the federal government. Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council (CESCC). 2011. Wild Species 2010: The General Status of Species in Canada. National General Status Working Group: 302 pp. Available in French under title: Espèces sauvages 2010: La situation générale des espèces au Canada. ii Abstract Wild Species 2010 is the third report of the series after 2000 and 2005. The aim of the Wild Species series is to provide an overview on which species occur in Canada, in which provinces, territories or ocean regions they occur, and what is their status. Each species assessed in this report received a rank among the following categories: Extinct (0.2), Extirpated (0.1), At Risk (1), May Be At Risk (2), Sensitive (3), Secure (4), Undetermined (5), Not Assessed (6), Exotic (7) or Accidental (8). In the 2010 report, 11 950 species were assessed. Many taxonomic groups that were first assessed in the previous Wild Species reports were reassessed, such as vascular plants, freshwater mussels, odonates, butterflies, crayfishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Other taxonomic groups are assessed for the first time in the Wild Species 2010 report, namely lichens, mosses, spiders, predaceous diving beetles, ground beetles (including the reassessment of tiger beetles), lady beetles, bumblebees, black flies, horse flies, mosquitoes, and some selected macromoths. The overall results of this report show that the majority of Canada’s wild species are ranked Secure. -

From Ghost and Mud Shrimp

Zootaxa 4365 (3): 251–301 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2017 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4365.3.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C5AC71E8-2F60-448E-B50D-22B61AC11E6A Parasites (Isopoda: Epicaridea and Nematoda) from ghost and mud shrimp (Decapoda: Axiidea and Gebiidea) with descriptions of a new genus and a new species of bopyrid isopod and clarification of Pseudione Kossmann, 1881 CHRISTOPHER B. BOYKO1,4, JASON D. WILLIAMS2 & JEFFREY D. SHIELDS3 1Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West @ 79th St., New York, New York 10024, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biology, Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York 11549, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Aquatic Health Sciences, Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William & Mary, P.O. Box 1346, Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] 4Corresponding author Table of contents Abstract . 252 Introduction . 252 Methods and materials . 253 Taxonomy . 253 Isopoda Latreille, 1817 . 253 Bopyroidea Rafinesque, 1815 . 253 Ionidae H. Milne Edwards, 1840. 253 Ione Latreille, 1818 . 253 Ione cornuta Bate, 1864 . 254 Ione thompsoni Richardson, 1904. 255 Ione thoracica (Montagu, 1808) . 256 Bopyridae Rafinesque, 1815 . 260 Pseudioninae Codreanu, 1967 . 260 Acrobelione Bourdon, 1981. 260 Acrobelione halimedae n. sp. 260 Key to females of species of Acrobelione Bourdon, 1981 . 262 Gyge Cornalia & Panceri, 1861. 262 Gyge branchialis Cornalia & Panceri, 1861 . 262 Gyge ovalis (Shiino, 1939) . 264 Ionella Bonnier, 1900 . -

Crecimiento Somático De La Langosta De Juan Fernández Jasus Frontalis (H

Universidad de Concepción Dirección de Postgrado Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas Programa de Magister en Ciencias con Mención en Pesquerías Crecimiento somático de la langosta de Juan Fernández Jasus frontalis (H. Milne Edwards, 1837) y evaluación del impacto de la talla mínima legal de extracción como táctica del manejo de su pesquería. PABLO MANRIQUEZ ANGULO CONCEPCIÓN-CHILE 2016 Profesor Guía: Billy Ernst Elizalde Depto. de Oceanografía Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas Universidad de Concepción La presente tesis se realizó en el Departamento de Oceanografía de la Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas de la Universidad de Concepción y ha sido aprobada por la siguiente Comisión Evaluadora: Profesor Guía ____________________________ Dr. Billy Ernst Elizalde Departamento de Oceanografía Universidad de Concepción Comisión Evaluadora ____________________________ Dr. Billy Ernst Elizalde Departamento de Oceanografía Universidad de Concepción ____________________________ Licenciado en Biología Marco Retamal Rivas Departamento de Oceanografía Universidad de Concepción ____________________________ M.Sc. Patricio Arana Espina Escuela de Ciencias del Mar Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso Director de Programa ____________________________ Dr. Luis Cubillos S. Departamento de Oceanografía Universidad de Concepción 2 Dedicada a mi familia Isleña y Porteña… Y a mi Hija que junto a mi pareja estuvieron conmigo estos últimos y difíciles meses… 3 Agradecimientos Antes que todo quisiera agradecer esta tesis, a mi esforzada y ejemplar “Familia Manríquez Angulo” compuesta por mi MADRE y HERMANO que descansan en Paz junto a mi Tata, a ellos le doy las gracias por esas energías que sentí en aquellos momentos en que ya no daba más… y a mi PADRE y HERMANA, que junto a mi Abi les agradezco por el apoyo incondicional que siempre me han dado ¡¡Los Amo!!. -

Guide to Crustacea

46 Guide to Crustacea. Order 2.—Decapoda. (Table-cases Nos. 9-16.) The gills are arranged typically in three series—podo- branchiae, arthrobranchiae, and pleurobranchiae. Only in the aberrant genus Leucifer are the gills entirely absent. The first three pairs of thoracic limbs are more or less completely modified to act as jaws (maxillipeds), while the last five form the legs. This very extensive and varied Order includes all the larger and more familiar Crustacea, such as Crabs, Lobsters, Crayfish, FIG. 30. Penaeus caramote, from the side, about half natural size. [Table-case No. 9.] Prawns, and Shrimps. From their greater size and more general interest, it is both possible and desirable to exhibit a much larger series than in the other groups of Crustacea, and in Table-cases Nos. 9 to 16 will be found representatives of all the Tribes and of the more important families composing the Order. On the system of classification adopted here, these tribes are grouped under three Sub-orders :— Sub-order 1.—Macrura. „ 2.—Anomura. ,, 3.—Brachyura. Eucarida—Decapoda. 47 SUB-ORDER I.— MACRURA. (Table-cases Nos. 9-11.) The Macrura are generally distinguished by the large size of the abdomen, which is symmetrical and not folded under the body. The front, or rostrum, is not united with the " epistome." The sixth pair of abdominal appendages (uropods) are always present, generally broad and flattened, forming with the telson, a " tail-fan." The first Tribe of the Macrura, the PENAEIDEA, consists of prawn-like animals having the first three pairs of legs usually chelate or pincer-like, and not differing greatly in size. -

First Record and Description of Panulirus Pascuensis (Reed, 1954) First Stage Phyllosoma in the Plankton of Rapa Nui

First record and description of Panulirus pascuensis (Reed, 1954) first stage phyllosoma in the plankton of Rapa Nui By Meerhoff Erika*, Mujica Armando, García Michel, and Nava María Luisa Abstract Among the most striking crustaceans from Rapa Nui Island (27° S, 109°22’ W) is the endemic lobster Panulirus pascuensis, commonly known as the spiny lobster. This species is also present in Pitcairn Island and the Salas y Gomez ridge. The larvae of this species pass through different phyllosoma stages until metamorphosis, in which they molt to puerulus, a transitional stage adapted to benthic life. This species is an important fishery resource for the inhabitants of Rapa Nui. However, there are several gaps in the biological knowledge of this species, including its ontogeny. We sampled zooplankton to obtain first stage P. pascuensis phyllosoma during three oceanographic campaigns around Rapa Nui (April 2015, September 2015 and March 2016), individuals were encountered between the surface and 200 m depth with an abundance of 1.3 indiv/1000 m3. These individuals, along with laboratory hatched phyllosoma, allowed us to describe the morphology of this larval stage. The P. pascuensis stage I phyllosoma were observed in fall, suggesting that the larval development would be synchronized with the productivity cycle in the region of Rapa Nui, where maximum chlorophyll concentration is observed during the austral winter. *Corresponding Author E-mail: [email protected] Pacific Science, vol. 71, no. 2 December 9, 2016 (Early view) Introduction The island of Rapa Nui (also known as Easter Island) is part of the Marine and Coastal Protected Area called Coral Nui Nui, Motu Tautara and Hanga Oteo submarine Parks (Sierralta et al. -

Metabolic Suppression in the Pelagic Crab, Pleuroncodes Planipes, in Oxygen Minimum Zones T ⁎ Brad A

Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part B 224 (2018) 88–97 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part B journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cbpb Metabolic suppression in the pelagic crab, Pleuroncodes planipes, in oxygen minimum zones T ⁎ Brad A. Seibela, , Bryan E. Luub,1, Shannon N. Tessierc,1, Trisha Towandad, Kenneth B. Storeyb a College of Marine Science, University of South Florida, 830 1st St. S., St. Petersburg, FL 33701, USA b Institute of Biochemistry & Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6, Canada c BioMEMS Resource Center & Center for Engineering in Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital & Harvard Medical School, 114 16th Street, Charlestown, MA 02129, USA d Evergreen State College, Olympia, WA, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The pelagic red crab, Pleuroncodes planipes, is abundant throughout the Eastern Tropical Pacific in both benthic Protein synthesis and pelagic environments to depths of several hundred meters. The oxygen minimum zones in this region Hypoxia reaches oxygen levels as low as 0.1 kPa at depths within the crabs vertical range. Crabs maintain aerobic me- Zooplankton tabolism to a critical PO2 of ~0.27 ± 0.2 kPa (10 °C), in part by increasing ventilation as oxygen declines. At Hypometabolism subcritical oxygen levels, they enhance anaerobic ATP production slightly as indicated by modest increases in Vertical migration lactate levels. However, hypoxia tolerance is primarily mediated via a pronounced suppression of aerobic me- tabolism (~70%). Metabolic suppression is achieved, primarily, via reduced protein synthesis, which is a major sink for metabolic energy. Posttranslational modifications on histone H3 suggest a condensed chromatin state and, hence, decreased transcription. -

Growth Patterns and Exploitation Status of the Spiny Lobster Species Palinurus Mauritanicus (Gruvel 1911) in Mauritanian Coasts

International Journal of Agricultural Policy and Research Vol.7 (2), pp. 17-31, March 2019 Available online at https://www.journalissues.org/IJAPR/ https://doi.org/10.15739/IJAPR.19.003 Copyright © 2019 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article ISSN 2350-1561 Original Research Article Growth patterns and exploitation status of the spiny lobster species Palinurus mauritanicus (Gruvel 1911) in Mauritanian coasts Received 3 January, 2019 Revised 10 February, 2019 Accepted 15 February, 2019 Published 14 March, 2019 Amadou Sow1, In the Mauritanian coasts, fishing effort on Palinurus mauritanicus Bilassé Zongo*2 contributes in the decline of the stock. From February to August 2015, samplings were carried out monthly in order to study the growth patterns and and the stock status to provide further information for sustainable 2 T. Jean André Kabre management and exploitation of the species. A total of 12008 individuals were collected. Total length (Lt) and cephalothoracic length (Lc) were 1Institut Mauritanien des measured with a vernier caliper. The species were separately weighed on a Recherches Océanographiques et digital balance and their sex noted. The collected data were entered on excel des Pêches (IMROP), Mauritanie spreadsheet in order to analyse growth kinetics, exploitation kinetics and 2Université Nazi Boni, LaRFPF, estimate fish mortality using FISAT II software. Male of P. mauritanicus had Burkina Faso an average Lc = 130 mm and an average Lc = 111 mm. The annual length frequency distribution gave respectively 6 and 7 age-groups for females and *Corresponding Author males. Lc-Lt relationship and Lc-Wt relationship showed a minor allometry Email: [email protected] (b < 3 for both). -

Marine Biodiversity in Juan Fernández and Desventuradas Islands, Chile: Global Endemism Hotspots

RESEARCH ARTICLE Marine Biodiversity in Juan Fernández and Desventuradas Islands, Chile: Global Endemism Hotspots Alan M. Friedlander1,2,3*, Enric Ballesteros4, Jennifer E. Caselle5, Carlos F. Gaymer3,6,7,8, Alvaro T. Palma9, Ignacio Petit6, Eduardo Varas9, Alex Muñoz Wilson10, Enric Sala1 1 Pristine Seas, National Geographic Society, Washington, District of Columbia, United States of America, 2 Fisheries Ecology Research Lab, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii, United States of America, 3 Millennium Nucleus for Ecology and Sustainable Management of Oceanic Islands (ESMOI), Coquimbo, Chile, 4 Centre d'Estudis Avançats (CEAB-CSIC), Blanes, Spain, 5 Marine Science Institute, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, California, United States of America, 6 Universidad Católica del Norte, Coquimbo, Chile, 7 Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Zonas Áridas, Coquimbo, Chile, 8 Instituto de Ecología y Biodiversidad, Coquimbo, Chile, 9 FisioAqua, Santiago, Chile, 10 OCEANA, SA, Santiago, Chile * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: Friedlander AM, Ballesteros E, Caselle JE, Gaymer CF, Palma AT, Petit I, et al. (2016) Marine The Juan Fernández and Desventuradas islands are among the few oceanic islands Biodiversity in Juan Fernández and Desventuradas belonging to Chile. They possess a unique mix of tropical, subtropical, and temperate Islands, Chile: Global Endemism Hotspots. PLoS marine species, and although close to continental South America, elements of the biota ONE 11(1): e0145059. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0145059 have greater affinities with the central and south Pacific owing to the Humboldt Current, which creates a strong biogeographic barrier between these islands and the continent. The Editor: Christopher J Fulton, The Australian National University, AUSTRALIA Juan Fernández Archipelago has ~700 people, with the major industry being the fishery for the endemic lobster, Jasus frontalis. -

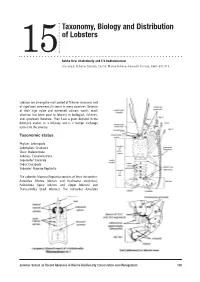

Taxonomy, Biology and Distribution of Lobsters

Taxonomy, Biology and Distribution of Lobsters 15 Rekha Devi Chakraborty and E.V.Radhakrishnan Crustacean Fisheries Division, Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi-682 018 Lobsters are among the most prized of fisheries resources and of significant commercial interest in many countries. Because of their high value and esteemed culinary worth, much attention has been paid to lobsters in biological, fisheries, and systematic literature. They have a great demand in the domestic market as a delicacy and is a foreign exchange earner for the country. Taxonomic status Phylum: Arthropoda Subphylum: Crustacea Class: Malacostraca Subclass: Eumalacostraca Superorder: Eucarida Order: Decapoda Suborder: Macrura Reptantia The suborder Macrura Reptantia consists of three infraorders: Astacidea (Marine lobsters and freshwater crayfishes), Palinuridea (Spiny lobsters and slipper lobsters) and Thalassinidea (mud lobsters). The infraorder Astacidea Summer School on Recent Advances in Marine Biodiversity Conservation and Management 100 Rekha Devi Chakraborty and E.V.Radhakrishnan contains three superfamilies of which only one (the Infraorder Palinuridea, Superfamily Eryonoidea, Family Nephropoidea) is considered here. The remaining two Polychelidae superfamilies (Astacoidea and parastacoidea) contain the 1b. Third pereiopod never with a true chela,in most groups freshwater crayfishes. The superfamily Nephropoidea (40 chelae also absent from first and second pereiopods species) consists almost entirely of commercial or potentially 3a Antennal flagellum reduced to a single broad and flat commercial species. segment, similar to the other antennal segments ..... Infraorder Palinuridea, Superfamily Palinuroidea, The infraorder Palinuridea also contains three superfamilies Family Scyllaridae (Eryonoidea, Glypheoidea and Palinuroidea) all of which are 3b Antennal flagellum long, multi-articulate, flexible, whip- marine. The Eryonoidea are deepwater species of insignificant like, or more rigid commercial interest.