A Study of the Comilla Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangladesh Jobs Diagnostic.” World Bank, Washington, DC

JOBS SERIES Public Disclosure Authorized Issue No. 9 Public Disclosure Authorized DIAGNOSTIC BANGLADESH Public Disclosure Authorized Main Report Public Disclosure Authorized JOBS DIAGNOSTIC BANGLADESH Thomas Farole, Yoonyoung Cho, Laurent Bossavie, and Reyes Aterido Main Report © 2017 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA. Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org. Some rights reserved This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the govern- ments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: Thomas Farole, Yoonyoung Cho, Laurent Bossavie, and Reyes Aterido. -

Trust Within Field Bureaucracy: a Study on District Administration in Bangladesh

Trust within Field Bureaucracy: A study on District Administration in Bangladesh Muhammad Anisuzzaman Thesis submitted for examination for the degree of Master of Public Policy and Governance. 2012 Master in Public Policy and Governance Program Department of General and Continuing Education North South University, Bangladesh i Dedication..... To my parents Without their love and support, I would be nowhere. i Abstract This study attempts to explore the dynamics of trust within the field bureaucracy in Bangladesh with special focus to find determining factors of interpersonal trust, and to analyze the relationship between trust in coworkers and trust in subordinate. The study uses the method of questionnaire survey to investigate interpersonal trust of the employees in three Deputy Commissioners offices located in Comilla, Rangamati and Gaziur. This study takes an important step forward by detailing how trust within local level bureaucratic workplace is influenced by socioeconomic background of the employees, personal traits of coworkers as well as personal and leadership characteristics of the superiors. It examines a number of hypotheses related to trust and socioeconomic background as well as interpersonal traits of the employees inside the organization. This study does not find relations of gender with interpersonal trust. It is found that gender does not play role in making trust in organization. Female may put higher trust than male in other societal relations but in working environment trust is not influenced by male-female issue. In case of age variable, the study finds that within a bureaucratic organization in developing country like Bangladesh old aged employees are more trusting and the middle aged employees within organization are less trusting. -

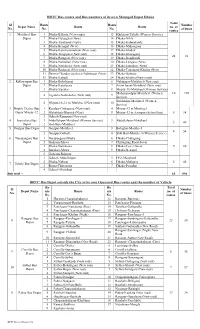

BRTC Bus Routes and Bus Numbers of Its Own Managed Depot Dhaka Total Sl Routs Routs Number Depot Name Routs Routs No

BRTC Bus routes and Bus numbers of its own Managed Depot Dhaka Total Sl Routs Routs Number Depot Name Routs Routs no. of No. No. No. of buses routes 1. Motijheel Bus 1 Dhaka-B.Baria (New routs) 13 Khilgoan-Taltola (Women Service) Depot 2 Dhaka-Haluaghat (New) 14 Dhaka-Nikli 3 Dhaka-Tarakandi (New) 15 Dhaka-Kalmakanda 4 Dhaka-Benapul (New) 16 Dhaka-Muhongonj 5 Dhaka-Kutichowmuhoni (New rout) 17 Dhaka-Modon 6 Dhaka-Tongipara (New rout) 18 Dhaka-Ishoregonj 24 82 7 Dhaka-Ramgonj (New rout) 19 Dhaka-Daudkandi 8 Dhaka-Nalitabari (New rout) 20 Dhaka-Lengura (New) 9 Dhaka-Netrakona (New rout) 21 Dhaka-Jamalpur (New) 10 Dhaka-Ramgonj (New rout) 22 Dhaka-Tongipara-Khulna (New) 11 Demra-Chandra via Savar Nabinagar (New) 23 Dhaka-Bajitpur 12 Dhaka-Katiadi 24 Dhaka-Khulna (New routs) 2. Kallayanpur Bus 1 Dhaka-Bokshigonj 6 Nabinagar-Motijheel (New rout) Depot 2 Dhaka-Kutalipara 7 Zirani bazar-Motijheel (New rout) 3 Dhaka-Sapahar 8 Mirpur-10-Motijheel (Women Service) Mohammadpur-Motijheel (Women 10 198 4 Zigatola-Notunbazar (New rout) 9 Service) Siriakhana-Motijheel (Women 5 Mirpur-10-2-1 to Motijheel (New rout) 10 Service) 3. Double Decker Bus 1 Kendua-Chittagong (New rout) 4 Mirpur-12 to Motijheel Depot Mirpur-12 2 Mohakhali-Bhairob (New) 5 Mirpur-12 to Azimpur (School bus) 5 38 3 Gabtoli-Rampura (New rout) 4. Joarsahara Bus 1 Abdullahpur-Motijheel (Women Service) 3 Abdullahpur-Motijheel 5 49 Depot 2 Shib Bari-Motijheel 5. Gazipur Bus Depot 1 Gazipur-Motijheel 3 Balughat-Motijheel 4 54 2 Gazipur-Gabtoli 4 Shib Bari-Motijheel (Women Service) 6. -

127 Branches

মেটলাইফ পলললির প্রিপ্রিয়াি ও অꇍযাꇍয মপমেন্ট বযা廬ক এপ্রিয়ার িকল শাখায় ꇍগদে প্রদান কমর তাৎক্ষপ্রিকভাদব বমু ে লনন ররপ্রভপ্রꇍউ স্ট্যাম্প ও সীলসহ রিটলাইদের প্ররপ্রসট এই িলু বধা পাওয়ার জনয গ্রাহকমক মকান অলিলরক্ত লফ অথবা স্ট্যাম্প চাজ জ প্রদান করমি হমব না Sl. No. Division District Name of Branches Address of Branch 1 Barisal Barisal Barishal Branch Fakir Complex 112 Birshrashtra Captain Mohiuddin Jahangir Sarak 2 Barisal Bhola Bhola Branch Nabaroon Center(1st Floor), Sadar Road, Bhola 3 Chittagong Chittagong Agrabad Branch 69, Agrabad C/ A, Chittagong 4 Chittagong Chittagong Anderkilla Branch 184, J.M Sen Avenue Anderkilla 5 Chittagong Chittagong Bahadderhat Branch Mamtaz Tower 4540, Bahadderhat 6 Chittagong Chittagong Bank Asia Bhaban Branch 39 Agrabad C/A Manoda Mansion (2nd Floor), Holding No.319, Ward No.3, College 7 Chittagong Comilla Barura Branch Road, Barura Bazar, Upazilla: Barura, District: Comilla. 8 Chittagong Chittagong Bhatiary Branch Bhatiary, Shitakunda 9 Chittagong Brahmanbaria Brahmanbaria Branch "Muktijoddha Complex Bhaban" 1061, Sadar Hospital Road 10 Chittagong Chittagong C.D.A. Avenue Branch 665 CDA Avenue, East Nasirabad 1676/G/1 River City Market (1st Floor), Shah Amant Bridge 11 Chittagong Chaktai Chaktai Branch connecting road 12 Chittagong Chandpur Chandpur Branch Appollo Pal Bazar Shopping, Mizanur Rahman Road 13 Chittagong Lakshmipur Chandragonj Branch 39 Sharif Plaza, Maddho Bazar, Chandragonj, Lakshimpur 14 Chittagong Noakhali Chatkhil Branch Holding No. 3147 Khilpara Road Chatkhil Bazar Chatkhil 15 Chittagong Comilla Comilla Branch Chowdhury Plaza 2, House- 465/401, Race Course 16 Chittagong Comilla Companigonj Branch Hazi Shamsul Hoque Market, Companygonj, Muradnagar J.N. -

Traditional Institutions As Tools of Political Islam in Bangladesh

01_riaz_055072 (jk-t) 15/6/05 11:43 am Page 171 Traditional Institutions as Tools of Political Islam in Bangladesh Ali Riaz Illinois State University, USA ABSTRACT Since 1991, salish (village arbitration) and fatwa (religious edict) have become common features of Bangladesh society, especially in rural areas. Women and non-governmental development organizations (NGOs) have been subjected to fatwas delivered through a traditional social institution called salish. This article examines this phenomenon and its relationship to the rise of Islam as political ideology and increasing strengths of Islamist parties in Bangladesh. This article challenges existing interpretations that persecution of women through salish and fatwa is a reaction of the rural community against the modernization process; that fatwas represent an important tool in the backlash of traditional elites against the impoverished rural women; and that the actions of the rural mullahs do not have any political links. The article shows, with several case studies, that use of salish and fatwa as tools of subjection of women and development organizations reflect an effort to utilize traditional local institutions to further particular interpretations of behavior and of the rights of indi- viduals under Islam, and that this interpretation is intrinsically linked to the Islamists’ agenda. Keywords: Bangladesh; fatwa; political Islam Introduction Although the alarming rise of the militant Islamists in Bangladesh and their menacing acts in the rural areas have received international media attention in recent days (e.g. Griswold, 2005), the process began more than a decade ago. The policies of the authoritarian military regimes that ruled Bangladesh between 1975 and 1990, and the politics of expediency of the two major politi- cal parties – the Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) – enabled the Islamists to emerge from the political wilderness to a legit- imate political force in the national arena (Riaz, 2003). -

Water Pricing for Slum Dwellers in Dhaka Metropolitan Area: Is It Affordable?

WATER PRICING FOR SLUM DWELLERS IN DHAKA METROPOLITAN AREA: IS IT AFFORDABLE? Muhammad Mizanur Rahaman*, Tahmid Saif Ahmed & Abdullah Al-Hadi Department of Civil Engineering, University of Asia Pacific, House 8, Road 7, Dhanmondi, Dhaka -1205, Bangladesh Fax: +88029664950 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Email: [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract Bangladesh is facing serious water management challenge to ensure affordable water supply for all, especially in urban areas. Both the availability and the quality of water are decreasing in the poor urban areas. Besides, the population situation of the country is getting worst in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, which became one of the megacities in the world in terms of population and urbanization. The aim of this research is to address the following question: “Are slum dwellers in Dhaka Metropolitan Area capable for paying for Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority’s (DWASA) services?”. This study focused on three slums in Dhaka Metropolitan Area namely Korail slum, Godown slum and Tejgaon slum to determine the current water price in these slums and to compare it with water price of other cities of the world. A field study has been conducted during July and August 2014. It involves semi structured questionnaire survey and focus group discussions with slum dwellers and various stakeholders. For secondary data source, a wide range of books, peer-reviewed articles, researcher documents, related websites and databases have been reviewed. Result shows that for domestic water use slum dwellers are paying about 7 to 14 times higher than legal connection holders covered by DWASA. -

Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 10 04 10 04

Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 BARISAL DIVISION 10 04 BARGUNA 10 04 09 AMTALI 10 04 19 BAMNA 10 04 28 BARGUNA SADAR 10 04 47 BETAGI 10 04 85 PATHARGHATA 10 04 92 TALTALI 10 06 BARISAL 10 06 02 AGAILJHARA 10 06 03 BABUGANJ 10 06 07 BAKERGANJ 10 06 10 BANARI PARA 10 06 32 GAURNADI 10 06 36 HIZLA 10 06 51 BARISAL SADAR (KOTWALI) 10 06 62 MHENDIGANJ 10 06 69 MULADI 10 06 94 WAZIRPUR 10 09 BHOLA 10 09 18 BHOLA SADAR 10 09 21 BURHANUDDIN 10 09 25 CHAR FASSON 10 09 29 DAULAT KHAN 10 09 54 LALMOHAN 10 09 65 MANPURA 10 09 91 TAZUMUDDIN 10 42 JHALOKATI 10 42 40 JHALOKATI SADAR 10 42 43 KANTHALIA 10 42 73 NALCHITY 10 42 84 RAJAPUR 10 78 PATUAKHALI 10 78 38 BAUPHAL 10 78 52 DASHMINA 10 78 55 DUMKI 10 78 57 GALACHIPA 10 78 66 KALAPARA 10 78 76 MIRZAGANJ 10 78 95 PATUAKHALI SADAR 10 78 97 RANGABALI Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 79 PIROJPUR 10 79 14 BHANDARIA 10 79 47 KAWKHALI 10 79 58 MATHBARIA 10 79 76 NAZIRPUR 10 79 80 PIROJPUR SADAR 10 79 87 NESARABAD (SWARUPKATI) 10 79 90 ZIANAGAR 20 CHITTAGONG DIVISION 20 03 BANDARBAN 20 03 04 ALIKADAM 20 03 14 BANDARBAN SADAR 20 03 51 LAMA 20 03 73 NAIKHONGCHHARI 20 03 89 ROWANGCHHARI 20 03 91 RUMA 20 03 95 THANCHI 20 12 BRAHMANBARIA 20 12 02 AKHAURA 20 12 04 BANCHHARAMPUR 20 12 07 BIJOYNAGAR 20 12 13 BRAHMANBARIA SADAR 20 12 33 ASHUGANJ 20 12 63 KASBA 20 12 85 NABINAGAR 20 12 90 NASIRNAGAR 20 12 94 SARAIL 20 13 CHANDPUR 20 13 22 CHANDPUR SADAR 20 13 45 FARIDGANJ -

Under Threat: the Challenges Facing Religious Minorities in Bangladesh Hindu Women Line up to Vote in Elections in Dhaka, Bangladesh

report Under threat: The challenges facing religious minorities in Bangladesh Hindu women line up to vote in elections in Dhaka, Bangladesh. REUTERS/Mohammad Shahisullah Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International This report has been produced with the assistance of the Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is a Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. non-governmental organization (NGO) working to secure The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and Minority Rights Group International, and can in no way be indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation taken to reflect the views of the Swedish International and understanding between communities. Our activities are Development Cooperation Agency. focused on international advocacy, training, publishing and outreach. We are guided by the needs expressed by our worldwide partner network of organizations, which represent minority and indigenous peoples. MRG works with over 150 organizations in nearly 50 countries. Our governing Council, which meets twice a year, has members from 10 different countries. MRG has consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Minority Rights Group International would like to thank Social Council (ECOSOC), and observer status with the Human Rights Alliance Bangladesh for their general support African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights in producing this report. Thank you also to Bangladesh (ACHPR). MRG is registered as a charity and a company Centre for Human Rights and Development, Bangladesh limited by guarantee under English law: registered charity Minority Watch, and the Kapaeeng Foundation for supporting no. 282305, limited company no. 1544957. the documentation of violations against minorities. -

Bangladesh Country Report 2018

. Photo: Children near an unsecured former smelting site in the Ashulia area outside of Dhaka Toxic Sites Identification Program in Bangladesh Award: DCI-ENV/2015/371157 Prepared by: Andrew McCartor Prepared for: UNIDO Date: November 2018 Pure Earth 475 Riverside Drive, Suite 860 New York, NY, USA +1 212 647 8330 www.pureearth.org List of Acronyms ...................................................................................................................... 1 List of Annexes ......................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction............................................................................................................................... 2 Background............................................................................................................................... 2 Toxic Sites Identification Program (TSIP) ............................................................................. 3 TSIP Training ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Implementation Strategy and Coordination with Government .......................................... 4 Program Implementation Activities ..................................................................................................... 4 Analysis of Environmental -

Impacts of Climate Variability on Major Food Crops in Selected Agro-Ecosystems of Bangladesh M

Ann.M. G. Bangladesh Miah, M. A. Agric. Rahman, (2016) M. 20(1 M. Rahman & 2) : 61-74 and S. R. Saha ISSN 1025-482X (Print)61 2521-5477 (Online) IMPACTS OF CLIMATE VARIABILITY ON MAJOR FOOD CROPS IN SELECTED AGRO-ECOSYSTEMS OF BANGLADESH M. G. Miah*1, M. A. Rahman1, M. M. Rahman1 and S. R. Saha1 Abstract The agriculture of Bangladesh has been recognized as one of the most vulnerable sectors to the impacts of climate change due to its juxtaposing geographical position. This study examined the nexus between long-term (1960–2014) climate variables with the yield and area of major food crops in selected agro-ecosystems (Gazipur, Comilla, Jessore, and Dinajpur) of Bangladesh. Secondary data from the Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) were used in analyzing climate variability for all the studied locations. Data of crop yields were collected from the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) local offices and respective farmers. Fifty farmers from each site were selected randomly and interviewed to investigate the farmers’ perceptions regarding the climate change phenomenon and its impact on crop production. Results showed the increasing trend of temperatures with time, which became more pronounced in Jessore and Dinajpur. Annual rainfall also revealed an increasing trend in all locations except Comilla. The analyses of Lower Confidence Level (LCL) and Upper Confidence Level (UCL) clearly indicated that the climate in recent years (1990–2014) changed conspicuously compared to that in 30 years ago (1960– 1989). Results of Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) indicated drought intensity, which was distinct in Dinajpur and Jessore. Although area under crop production had declined, yields showed an increasing trend in all locations because of technological advances. -

A Study on the Impact of the 2Nd Bur/Ganga Bridge on the Physical and Socio-Economic Condition of Keraniganj Upazila

• A STUDY ON THE IMPACT OF THE 2ND BUR/GANGA BRIDGE ON THE PHYSICAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC CONDITION OF KERANIGANJ UPAZILA • MASTER OF URBAN & REGIONAL PLANNING DEPARTMENT OF URBAN & REGIONAL PLANNING BANGLADESH UNIVERSITY OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY (DUET) April. 2009 \ CERTIFICATE The thesis titled "A STUDY ON THI': IMP4..CT OF THI': 2NI> BliRIGANGA BRIDGI': O~ THF: PHYSICAL ANI) SOCIO-ECOI\'OMIC CO:'lDiTIOI\' OF KERAl\"IGANJ UPAZILA" submitted by RUMANA AKIITER Roll No,: 040415015F. Session: April, 2004 ha, heen accepted as satisfactory in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Muster ofUrhan and Regional Planning (MURP) on 04 April, 2009 Board of Examiners ~-- Dr, Shakil Akther Chairman Assi~tunt Professor (Supervi~()J'), Dept. ofUrb",n & Regwnal Planning HUST, Dhaka 1000 i2~e_~ Dr. Roxana Hafiz Ahmed Member Professor and Head (Ex-Officio) Dep! of'Urhan & Regional Planning BUEI, Dlmka 1000 cA~'~';JJ:~Irt-~ Dr. Asif-ul-Zuman Kli"'an Member A,sistan! P1'Ofessnr Dept. of Urban & Regionul Planning HUE!, Dhaka 1000 I:s~_\ "",_\ '_1_ Dr Nurullslam Nuy-eem Member Professor (External) Department of Geography and Environmem Uni ver,it y of Dhaka Dhli 1000 'I CANDIDATE'S DECLARATION It IS hereby declared that this thesis or any part o£il has not been submitted elsewhere fOfthe award of any degree or diploma. Signature of/he cand,date Rumana Akhter '." Acknowledgement First, I would like to express my gratitude to almighty Allah gives me ulhmate strength. I would like to acknowledge deep gratitude 10 my thesis supervisor, Dr, Mohammad Shakll Akther, Assistant Professor, Departmem of Uman and Regional Planmng, Bangladesh Universrty of Engineering and Technology. -

Land Resource Appraisal of Bangladesh for Agricultural

BGD/81/035 Technical Report 3 Volume II LAND RESOURCES APPRAISAL OF BANGLADESH FOR AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT REPORT 3 LAND RESOURCES DATA BASE VOLUME II SOIL, LANDFORM AND HYDROLOGICAL DATA BASE A /UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FAo FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION vJ OF THE UNITED NATIONS BGD/81/035 Technical Report 3 Volume II LAND RESOURCES APPRAISAL OF BANGLADESH FOR AGRICULTURALDEVELOPMENT REPORT 3 LAND RESOURCES DATA BASE VOLUME II SOIL, LANDFORM AND HYDROLOGICAL DATA BASE Report prepared for the Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations acting as executing agency for the United Nations Development Programme based on the work of H. Brammer Agricultural Development Adviser J. Antoine Data Base Management Expert and A.H. Kassam and H.T. van Velthuizen Land Resources and Agricultural Consultants UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 1988 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and AgricultureOrganization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored ina retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopyingor otherwise, without the prior perrnission of (he copyright owner. Applications for such permission,with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressedto the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viadelle Terme di Caracarla, 00100 Home, Italy.