'Thana's in Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socio-Economic Impact of Cropland Agroforestry: Evidence from Jessore District of Bangladesh

International Journal of Research in Agriculture and Forestry Volume 2, Issue 1, January 2015, PP 11-20 ISSN 2394-5907 (Print) & ISSN 2394-5915 (Online) Socio-Economic Impact of Cropland Agroforestry: Evidence from Jessore District of Bangladesh M. Chakraborty1, M.Z. Haider2, M.M. Rahaman3 1 MDS Graduate, Economics Discipline, Khulna University, Khulna – 9208, Bangladesh 2 Professor, Economics Discipline, Khulna University, Khulna – 9208, Bangladesh 3 MDS Graduate, Economics Discipline, Khulna University, Khulna – 9208, Bangladesh Abstract: This study attempts to explore the socio-economic impact of cropland agroforestry in Bangladesh. We surveyed 84 farmers of two sub-districts named Manirampur and Bagherpara under Jessore district in the south-west region of Bangladesh through using a questionnaire during the period of June to July 2013. It follows a multistage random sampling procedure for selecting respondents. The main objective of the study is to assess the socio-economic impact of Cropland Agroforestry (CAF) on farmers’ livelihood. The survey results reveal that CAF farmers’ socio-economic status is better than that of Non-Cropland Agroforestry (NCAF) or monoculture farmers. This study finds that housing pattern, level of education, land and other physical assets are significantly different between CAF and NCAF farmers. The mean annual household income of the surveyed CAF farmers is Tk. 0.19 million which is significantly higher (p<0.05) than that of the surveyed NCAF farmers. Household income also varies widely according to farm size and number of members in a household. The Weighted Mean Index (WMI) of five major indicators of farmer’s household livelihood situation reveals that CAF farmer’s household energy and food situation, affordability of education, medical and clothing expenditure is better than NCAF farmers. -

Bangladesh Jobs Diagnostic.” World Bank, Washington, DC

JOBS SERIES Public Disclosure Authorized Issue No. 9 Public Disclosure Authorized DIAGNOSTIC BANGLADESH Public Disclosure Authorized Main Report Public Disclosure Authorized JOBS DIAGNOSTIC BANGLADESH Thomas Farole, Yoonyoung Cho, Laurent Bossavie, and Reyes Aterido Main Report © 2017 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA. Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org. Some rights reserved This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the govern- ments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: Thomas Farole, Yoonyoung Cho, Laurent Bossavie, and Reyes Aterido. -

34418-023: Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources

Semiannual Environmental Monitoring Report Project No. 34418-023 December 2018 Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources Planning and Management Project - Additional Financing Prepared by Bangladesh Water Development Board for the People’s Republic of Bangladesh and the Asian Development Bank. This Semiannual Environmental Monitoring Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Semi-Annual Environmental Monitoring Report, SAIWRPMP-AF, July-December 2018 Bangladesh Water Development Board SEMI-ANNUAL ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING REPORT [Period July – December 2018] FOR Southwest Area Integrated Water Resources Planning and Management Project- Additional Financing Project Number: GoB Project No. 5151 Full Country Name: Bangladesh Financed by: ADB and Government of Bangladesh Prepared by: Bangladesh Water Development Board, Under Ministry of Water Resources, Govt. of Bangladesh. For: Asian Development Bank December 2018 Page | i Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... ii Executive -

Chapter 1 Introduction Main Report CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Main Report Chapter 1 Introduction Main Report CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study The Peoples Republic of Bangladesh has a population of 123 million (as of June 1996) and a per capita GDP (Fiscal Year 1994/1995) of US$ 235.00. Of the 48 nations categorized as LLDC, Bangladesh is the most heavily populated. Even after gaining independence, the nation repeatedly suffers from floods, cyclones, etc.; 1/3 of the nation is inundated every year. Shortage in almost all sectors (e.g. development funds, infrastructure, human resources, natural resources, etc.) also leaves both urban and rural regions very underdeveloped. The supply of safe drinking water is an issue of significant importance to Bangladesh. Since its independence, the majority of the population use surface water (rivers, ponds, etc.) leading to rampancy in water-borne diseases. The combined efforts of UNICEF, WHO, donor countries and the government resulted in the construction of wells. At present, 95% of the national population depend on groundwater for their drinking water supply, consequently leading to the decline in the mortality rate caused by contagious diseases. This condition, however, was reversed in 1990 by problems concerning contamination brought about by high levels of arsenic detected in groundwater resources. Groundwater contamination by high arsenic levels was officially announced in 1993. In 1994, this was confirmed in the northwestern province of Nawabganji where arsenic poisoning was detected. In the province of Bengal, in the western region of the neighboring nation, India, groundwater contamination due to high arsenic levels has been a problem since the 1980s. -

Trust Within Field Bureaucracy: a Study on District Administration in Bangladesh

Trust within Field Bureaucracy: A study on District Administration in Bangladesh Muhammad Anisuzzaman Thesis submitted for examination for the degree of Master of Public Policy and Governance. 2012 Master in Public Policy and Governance Program Department of General and Continuing Education North South University, Bangladesh i Dedication..... To my parents Without their love and support, I would be nowhere. i Abstract This study attempts to explore the dynamics of trust within the field bureaucracy in Bangladesh with special focus to find determining factors of interpersonal trust, and to analyze the relationship between trust in coworkers and trust in subordinate. The study uses the method of questionnaire survey to investigate interpersonal trust of the employees in three Deputy Commissioners offices located in Comilla, Rangamati and Gaziur. This study takes an important step forward by detailing how trust within local level bureaucratic workplace is influenced by socioeconomic background of the employees, personal traits of coworkers as well as personal and leadership characteristics of the superiors. It examines a number of hypotheses related to trust and socioeconomic background as well as interpersonal traits of the employees inside the organization. This study does not find relations of gender with interpersonal trust. It is found that gender does not play role in making trust in organization. Female may put higher trust than male in other societal relations but in working environment trust is not influenced by male-female issue. In case of age variable, the study finds that within a bureaucratic organization in developing country like Bangladesh old aged employees are more trusting and the middle aged employees within organization are less trusting. -

Evaluation of Drinking Water Quality in Jessore District, Bangladesh

IOSR Journal of Biotechnology and Biochemistry (IOSR-JBB) ISSN: 2455-264X, Volume 3, Issue 4 (Jul. – Aug. 2017), PP 59-62 www.iosrjournals.org Evaluation of Drinking Water Quality in Jessore District, Bangladesh Siddhartha sarder1, Md. Nazim Uddin2,* Md. Shamim Reza3 and A.H.M. Nasimul Jamil4 1Department of Chemistry, Military Collegiate School Khulna (MCSK), Bangladesh. 2,4Department of Chemistry, Khulna University of Engineering and Technology,Khulna, Bangladesh.3Department of Chemistry, North Western University, Khulna, Bangladesh. * Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: This study emphasized on ensuring quality of drinking water in Jessore district. Drinking Water quality was evaluated by measuring 12 parameters. These parameters were Arsenic (As), Cadmium (Cd), Iron (Fe), lead (Pb), Dissolved oxygen (DO), Chemical oxygen demand (COD), Biological oxygen demand (BOD) Chloride, Calcium (Ca), pH, Salinity andHardness CaCO3. All measured parameters were compared with water quality parameters Bangladesh standards & WHO guide lines. From the experimental results it can be conclude that all of the parameters were in standard ranges except Salinity, Arsenic, Iron, COD and BOD. The average value of Arsenic within permissible limits but other four parameters Salinity, Iron, COD and BOD average value were above the standard permissible limit. Keywords: Water quality,Jessore district, Drinking water and water quality parameters. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Performance of Different Gladiolus Varieties Under the Climatic Condition of Tista Meander Floodplain in Bangladesh

Progressive Agriculture 28 (3): 198-203, 2017 ISSN: 1017 - 8139 Performance of different Gladiolus varieties under the climatic condition of Tista Meander Floodplain in Bangladesh 1 1* 1 1 2 MK Islam , M Anwar , AU Alam , US Khatun , KA Ara 1On Farm Research Division, Agricultural Research Station, Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute, Alamnagar, Rangpur, Bangladesh; 2Horticulture Research Center, Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute, Joydebpur, Gazipur, Bangladesh Abstract An experiment was conducted to evaluate 4 cultivars of Gladiolus BARI Gladiolus 1, BARI Gladiolus 3, BARI Gladiolus 4 and BARI Gladiolus 5at experimental farm, On Farm Research Division, Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI), Alamnagar, Rangpur during 2015-2016 and 2016-2017. The aim of study was to evaluate the adaptability and performance of cultivar under the climatic conditions of Tista Mendar Floodplain Agro Ecological Zone in Bangladesh. Among the varieties BARI Gladiolus-5 performed excellent in terms of spike production in 2015-2016 and BARI Gladiolus-4 performed excellent in terms of spike production in 2016-2017. Among the varieties BARI Gladiolus-4performed excellent in terms of market value in both the years. Maximum spike length was observed in cultivars BARI Gladiolus-4 and BARI Gladiolus-5 remain attractive for longer time. Keeping in view the vegetative and reproductive characteristic cultivars BARI Gladiolus-4 was performed better and recommended for general cultivation. In 2015-2016 the highest gross return (BDT. 1383800 ha-1) as well as gross margin (BDT. 1005144 ha-1) was recorded in BARI Gladiolus-4. In 2016-2017 the highest gross return (BDT. 1318553ha-1) as well as gross margin (BDT. -

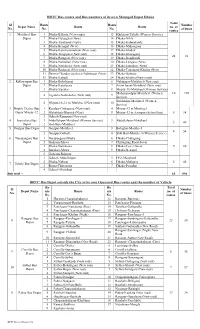

BRTC Bus Routes and Bus Numbers of Its Own Managed Depot Dhaka Total Sl Routs Routs Number Depot Name Routs Routs No

BRTC Bus routes and Bus numbers of its own Managed Depot Dhaka Total Sl Routs Routs Number Depot Name Routs Routs no. of No. No. No. of buses routes 1. Motijheel Bus 1 Dhaka-B.Baria (New routs) 13 Khilgoan-Taltola (Women Service) Depot 2 Dhaka-Haluaghat (New) 14 Dhaka-Nikli 3 Dhaka-Tarakandi (New) 15 Dhaka-Kalmakanda 4 Dhaka-Benapul (New) 16 Dhaka-Muhongonj 5 Dhaka-Kutichowmuhoni (New rout) 17 Dhaka-Modon 6 Dhaka-Tongipara (New rout) 18 Dhaka-Ishoregonj 24 82 7 Dhaka-Ramgonj (New rout) 19 Dhaka-Daudkandi 8 Dhaka-Nalitabari (New rout) 20 Dhaka-Lengura (New) 9 Dhaka-Netrakona (New rout) 21 Dhaka-Jamalpur (New) 10 Dhaka-Ramgonj (New rout) 22 Dhaka-Tongipara-Khulna (New) 11 Demra-Chandra via Savar Nabinagar (New) 23 Dhaka-Bajitpur 12 Dhaka-Katiadi 24 Dhaka-Khulna (New routs) 2. Kallayanpur Bus 1 Dhaka-Bokshigonj 6 Nabinagar-Motijheel (New rout) Depot 2 Dhaka-Kutalipara 7 Zirani bazar-Motijheel (New rout) 3 Dhaka-Sapahar 8 Mirpur-10-Motijheel (Women Service) Mohammadpur-Motijheel (Women 10 198 4 Zigatola-Notunbazar (New rout) 9 Service) Siriakhana-Motijheel (Women 5 Mirpur-10-2-1 to Motijheel (New rout) 10 Service) 3. Double Decker Bus 1 Kendua-Chittagong (New rout) 4 Mirpur-12 to Motijheel Depot Mirpur-12 2 Mohakhali-Bhairob (New) 5 Mirpur-12 to Azimpur (School bus) 5 38 3 Gabtoli-Rampura (New rout) 4. Joarsahara Bus 1 Abdullahpur-Motijheel (Women Service) 3 Abdullahpur-Motijheel 5 49 Depot 2 Shib Bari-Motijheel 5. Gazipur Bus Depot 1 Gazipur-Motijheel 3 Balughat-Motijheel 4 54 2 Gazipur-Gabtoli 4 Shib Bari-Motijheel (Women Service) 6. -

127 Branches

মেটলাইফ পলললির প্রিপ্রিয়াি ও অꇍযাꇍয মপমেন্ট বযা廬ক এপ্রিয়ার িকল শাখায় ꇍগদে প্রদান কমর তাৎক্ষপ্রিকভাদব বমু ে লনন ররপ্রভপ্রꇍউ স্ট্যাম্প ও সীলসহ রিটলাইদের প্ররপ্রসট এই িলু বধা পাওয়ার জনয গ্রাহকমক মকান অলিলরক্ত লফ অথবা স্ট্যাম্প চাজ জ প্রদান করমি হমব না Sl. No. Division District Name of Branches Address of Branch 1 Barisal Barisal Barishal Branch Fakir Complex 112 Birshrashtra Captain Mohiuddin Jahangir Sarak 2 Barisal Bhola Bhola Branch Nabaroon Center(1st Floor), Sadar Road, Bhola 3 Chittagong Chittagong Agrabad Branch 69, Agrabad C/ A, Chittagong 4 Chittagong Chittagong Anderkilla Branch 184, J.M Sen Avenue Anderkilla 5 Chittagong Chittagong Bahadderhat Branch Mamtaz Tower 4540, Bahadderhat 6 Chittagong Chittagong Bank Asia Bhaban Branch 39 Agrabad C/A Manoda Mansion (2nd Floor), Holding No.319, Ward No.3, College 7 Chittagong Comilla Barura Branch Road, Barura Bazar, Upazilla: Barura, District: Comilla. 8 Chittagong Chittagong Bhatiary Branch Bhatiary, Shitakunda 9 Chittagong Brahmanbaria Brahmanbaria Branch "Muktijoddha Complex Bhaban" 1061, Sadar Hospital Road 10 Chittagong Chittagong C.D.A. Avenue Branch 665 CDA Avenue, East Nasirabad 1676/G/1 River City Market (1st Floor), Shah Amant Bridge 11 Chittagong Chaktai Chaktai Branch connecting road 12 Chittagong Chandpur Chandpur Branch Appollo Pal Bazar Shopping, Mizanur Rahman Road 13 Chittagong Lakshmipur Chandragonj Branch 39 Sharif Plaza, Maddho Bazar, Chandragonj, Lakshimpur 14 Chittagong Noakhali Chatkhil Branch Holding No. 3147 Khilpara Road Chatkhil Bazar Chatkhil 15 Chittagong Comilla Comilla Branch Chowdhury Plaza 2, House- 465/401, Race Course 16 Chittagong Comilla Companigonj Branch Hazi Shamsul Hoque Market, Companygonj, Muradnagar J.N. -

Language, Identity and the State in Pakistan, 1947-48

Journal of Political Studies, Vol. 25, Issue - 1, 2018, 199:214 Language, Identity and the State in Pakistan, 1947-48 Dr Yaqoob Khan Bangash Abstract The question of language and identity has been a very contentious issue in Pakistan since its inception. As the creation of Pakistan was predicated on a single 'Muslim nation,' it was easily assumed that this nation would be monolithic and especially only have one common language, which was deemed to be Urdu. However, while Urdu was the lingua franca of the Muslim elite in northern India, in large parts of Muslim India it was almost an alien language. Therefore, the meshing of a religious identity with that of a national identity quickly became a major problem in Pakistan as soon as it was created. Focusing on the first year after its creation, this paper assesses the inception of the language issue in Pakistan in 1947-48. Taking the debate on language in the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan in February 1948, and the subsequent views of the founder and first Governor General of the country, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, during his March 1948 tour of East Bengal, this paper exhibits the fraught nature of the debate on language in Pakistan. It clearly shows how a very small issue was blown out of proportion, setting the stage for the grounding of a language rights movement which created unease and resentment in large parts of the country, ultimately leading to its vivisection in 1971. Keywords: Pakistan, Language, East Bengal, Bengali, Urdu, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Liaquat Ali Khan, Pakistan National Congress, Constituent Assembly of Pakistan. -

Traditional Institutions As Tools of Political Islam in Bangladesh

01_riaz_055072 (jk-t) 15/6/05 11:43 am Page 171 Traditional Institutions as Tools of Political Islam in Bangladesh Ali Riaz Illinois State University, USA ABSTRACT Since 1991, salish (village arbitration) and fatwa (religious edict) have become common features of Bangladesh society, especially in rural areas. Women and non-governmental development organizations (NGOs) have been subjected to fatwas delivered through a traditional social institution called salish. This article examines this phenomenon and its relationship to the rise of Islam as political ideology and increasing strengths of Islamist parties in Bangladesh. This article challenges existing interpretations that persecution of women through salish and fatwa is a reaction of the rural community against the modernization process; that fatwas represent an important tool in the backlash of traditional elites against the impoverished rural women; and that the actions of the rural mullahs do not have any political links. The article shows, with several case studies, that use of salish and fatwa as tools of subjection of women and development organizations reflect an effort to utilize traditional local institutions to further particular interpretations of behavior and of the rights of indi- viduals under Islam, and that this interpretation is intrinsically linked to the Islamists’ agenda. Keywords: Bangladesh; fatwa; political Islam Introduction Although the alarming rise of the militant Islamists in Bangladesh and their menacing acts in the rural areas have received international media attention in recent days (e.g. Griswold, 2005), the process began more than a decade ago. The policies of the authoritarian military regimes that ruled Bangladesh between 1975 and 1990, and the politics of expediency of the two major politi- cal parties – the Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) – enabled the Islamists to emerge from the political wilderness to a legit- imate political force in the national arena (Riaz, 2003). -

Water Pricing for Slum Dwellers in Dhaka Metropolitan Area: Is It Affordable?

WATER PRICING FOR SLUM DWELLERS IN DHAKA METROPOLITAN AREA: IS IT AFFORDABLE? Muhammad Mizanur Rahaman*, Tahmid Saif Ahmed & Abdullah Al-Hadi Department of Civil Engineering, University of Asia Pacific, House 8, Road 7, Dhanmondi, Dhaka -1205, Bangladesh Fax: +88029664950 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Email: [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract Bangladesh is facing serious water management challenge to ensure affordable water supply for all, especially in urban areas. Both the availability and the quality of water are decreasing in the poor urban areas. Besides, the population situation of the country is getting worst in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, which became one of the megacities in the world in terms of population and urbanization. The aim of this research is to address the following question: “Are slum dwellers in Dhaka Metropolitan Area capable for paying for Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority’s (DWASA) services?”. This study focused on three slums in Dhaka Metropolitan Area namely Korail slum, Godown slum and Tejgaon slum to determine the current water price in these slums and to compare it with water price of other cities of the world. A field study has been conducted during July and August 2014. It involves semi structured questionnaire survey and focus group discussions with slum dwellers and various stakeholders. For secondary data source, a wide range of books, peer-reviewed articles, researcher documents, related websites and databases have been reviewed. Result shows that for domestic water use slum dwellers are paying about 7 to 14 times higher than legal connection holders covered by DWASA.