VIEW the Théâtre De La Mode in Its Own Words

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 2019 Director’S Letter

Summer 2019 Director’s Letter Dear Members, Summer in the Northwest is a glorious time of year. It is also notoriously busy. If you are like most people, you are eager fill your weekends with fun and adventure. Whether you are re-visiting some of your favorite places or discovering new ones, I hope Maryhill is on your summer short list. We certainly have plenty to tempt you. On July 13 we open the special exhibition West Coast Woodcut: Contemporary Relief Prints by Regional Artists, which showcases some of the best printmakers of the region. The 60 prints on view feature masterfully rendered landscapes, flora and fauna of the West coast, along with explorations of social and environmental issues. Plein air artists will be back in action this summer when the 2019 Pacific Northwest Plein Air in the Columbia River Gorge kicks off in late July; throughout August we will exhibit their paintings in the museum’s M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust Education Center. The show is always a delight and I look forward to seeing the Gorge through the eyes of these talented artists. Speaking of the Gorge — we are in the thick of it with the Exquisite Gorge Project, a collaborative printmaking effort that has brought together 11 artists to create large-scale woodblock prints reflective of a 220-mile stretch of the Columbia River. On August 24 we invite you to participate in the culmination of the project as the print blocks are inked, laid end-to-end and printed using a steamroller on the grounds at Maryhill. -

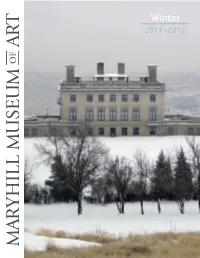

Winter 2011–2012 Dear Members & Friends

Winter 2011–2012 Dear Members & Friends, It’s trulY NOT AN UNDERSTATEMENT to say that Maryhill Museum of Art has had a monumental year. Last fall we received a generous challenge grant from the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust and in February held a groundbreaking for the first expansion in the museum’s history. On hand for the occasion were numerous members, donors and museum supporters who have worked hard to make the expansion project – many years in the making – a reality. Capital Campaign co-chair Laura Cheney, whose mother, Mary Hoyt Stevenson, provided the $2.6 million lead gift that made this new wing possible, was there to hoist a golden shovel and spoke eloquently about her mother’s dream for Maryhill. Top and bottom right: The Mary and Bruce Stevenson Wing Mary Stevenson became involved at Maryhill first as a volunteer expansion. Drawings by Craig Holmes. and later as a financial supporter of the museum. She served on the museum’s Board of Trustees for nearly 10 years and supported Maryhill Hits Halfway Mark Maryhill through gifts to exhibits, programs, the endowment to Meet M.J. Murdock and Fund for the Future, which she began in 1993 with a gift of Charitable Trust Challenge $1 million. Other gifts followed, many through the Mary Hoyt In January 2011, Maryhill Museum Stevenson Foundation. Mary’s love of art extended beyond of Art’s capital campaign received Maryhill. She served two terms on the Washington State Arts a substantial boost in the form of Commission and on the board of Portland’s Contemporary a 2:1 matching grant from the M.J. -

Givenchy Exudes French Elegance at Expo Classic Luxury Brand Showcasing Latest Stylish Products for Chinese Customers

14 | FRANCE SPECIAL Wednesday, November 6, 2019 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY Givenchy exudes French elegance at expo Classic luxury brand showcasing latest stylish products for Chinese customers This lipstick is a tribute and hom Givenchy has made longstanding age to the first Rouge Couture lip ties with China and a fresh resonance stick created by Hubert James Taffin in the country. The Mini Eden bag (left) de Givenchy, which had a case and Mini Mystic engraved with multiples 4Gs. History of style handbag are Givenchy’s Thirty years after Givenchy Make The history of Givenchy is a centerpieces at the CIIE. up was created, these two shades also remarkable one. have engraved on them the same 4Gs. The House of Givenchy was found In 1952, Hubert James Taffin de ed by Hubert de Givenchy in 1952. Givenchy debuted a collection of “sep The name came to epitomize stylish arates” — elegant blouses and light elegance, and many celebrities of the skirts with architectural lines. Accom age made Hubert de Givenchy their panied by the most prominent designer of choice. designers of the time, he established When Hubert de Givenchy arrived new standards of elegance and in Paris from the small town of Beau launched his signature fragrance, vais at the age of 17, he knew he want L’Interdit. ed to make a career in fashion design. In 1988, Givenchy joined the He studied at the Ecole des Beaux LVMH Group, where the couturier Arts in Versailles and worked as an remained until he retired in 1995. assistant to the influential designer, Hubert de Givenchy passed away Jacques Fath. -

Angkor Redux: Colonial Exhibitions in France

Angkor Redux: Colonial Exhibitions in France Dawn Rooney offers tantalising glimpses of late 19th-early 20th century exhibitions that brought the glory of Angkor to Europe. “I saw it first at the Paris Exhibition of 1931, a pavilion built of concrete treated to look like weathered stone. It was the outstanding feature of the exhibition, and at evening was flood-lit F or many, such as Claudia Parsons, awareness of the with yellow lighting which turned concrete to Angkorian kingdom and its monumental temples came gold (Fig. 1). I had then never heard of Angkor through the International Colonial Exhibitions held in Wat and thought this was just a flight of fancy, France in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries a wonder palace built for the occasion, not a copy of a temple long existent in the jungle of when French colonial presence in the East was at a peak. French Indo-China. Much earlier, the Dutch had secured domination over Indonesia, the Spanish in the Philippines, and the British But within I found photographs and read in India and Burma. France, though, did not become a descriptions that introduced me to the real colonial power in Southeast Asia until the last half of the Angkor and that nest of temples buried with it nineteenth century when it obtained suzerainty over Cam- in the jungle. I became familiar with the reliefs bodia, Vietnam (Cochin China, Tonkin, Annam) and, lastly, and carved motifs that decorated its walls, Laos. Thus, the name ‘French Indochina’ was coined not and that day I formed a vow: Some day . -

Fashion Arts. Curriculum RP-54. INSTITUTION Ontario Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 048 223 SP 007 137 TITLE Fashion Arts. Curriculum RP-54. INSTITUTION Ontario Dept. of Education, Toronto. PUB LATE 67 NOTE 34p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Clothing Instruction, *Curriculum Guides, Distributive Education, *Grade 11, *Grade 12, *Hcme Economics, Interior Design, *Marketing, Merchandising, Textiles Instruction AESTRACT GRADES OR AGES: Grades 11 and 12. SUBJECT MATTER: Fashicn arts and marketing. ORGANIZATION AND PHkSTCAL APPEARANCE: The guide is divided into two main sections, one for fashion arts and one for marketing, each of which is further subdivided into sections fcr grade 11 and grade 12. Each of these subdivisions contains from three to six subject units. The guide is cffset printed and staple-todnd with a paper cover. Oi:IJECTIVE3 AND ACTIVITIES' Each unit contains a short list of objectives, a suggested time allotment, and a list of topics to he covered. There is only occasional mention of activities which can he used in studying these topics. INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS: Each unit contains lists of books which relate either to the unit as a whole or to subtopics within the unit. In addition, appendixes contain a detailed list of equipment for the fashion arts course and a two-page billiography. STUDENT A. ,'SSMENT:No provision. (RT) U $ DEPARTMENT OF hEALTH EOUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF THIS DOCUMENTEOUCATION HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACT' VAS RECEIVED THE PERSON OR FROM INAnNO IT POINTSORGANIZATION ()RIG IONS STATED OF VIEW OR DO NUT OPIN REPRESENT OFFICIAL NECESSARILY CATION -

LE BOIS DE BOULOGNE Candidature De Paris Pour Les Jeux Olympiques De 2012 Et Plan D’Aménagement Durable Du Bois À L’Horizon 2012

ATELIER PARISIEN D’URBANISME - 17, BD MORLAND – 75004 PARIS – TÉL : 0142712814 – FAX : 0142762405 – http://www.apur.org LE BOIS DE BOULOGNE Candidature de Paris pour les Jeux Olympiques de 2012 et plan d’aménagement durable du bois à l’horizon 2012 Convention 2005 Jeux Olympiques de 2012 l’héritage dans les quartiers du noyau ouest en particulier dans le secteur de la porte d’Auteuil ___ Document février 2005 Le projet de jeux olympiques à Paris en 2012 est fondé sur la localisation aux portes de Paris de deux noyaux de sites de compétition à égale distance du village olympique et laissant le coeur de la capitale libre pour la célébration ; la priorité a par ailleurs été donnée à l'utilisation de sites existants et le nombre de nouveaux sites de compétition permanents a été réduit afin de ne répondre qu'aux besoins clairement identifiés. Le projet comprend : - le noyau Nord, autour du stade de France jusqu’à la porte de la Chapelle ; - le noyau Ouest, autour du bois de Boulogne tout en étant ancré sur les sites sportifs de la porte de Saint Cloud ; - à cela s’ajoutent un nombre limité de sites de compétition « hors noyaux » en région Ile de France et en province, en particulier pour les épreuves de football, ainsi que 2 sites dans le centre de Paris (Tour Eiffel et POPB). Sur chaque site, le projet s’efforce de combiner deux objectifs : permettre aux jeux de se dérouler dans les meilleures conditions pour les sportifs, les visiteurs et les spectateurs ; mais également apporter en héritage le plus de réalisations et d’embellissements pour les sites et leurs habitants. -

© 2018 Weronika Gaudyn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2018 Weronika Gaudyn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED STUDY OF HAUTE COUTURE FASHION SHOWS AS PERFORMANCE ART A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Weronika Gaudyn December 2018 STUDY OF HAUTE COUTURE FASHION SHOWS AS PERFORMANCE ART Weronika Gaudyn Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor School Director Mr. James Slowiak Mr. Neil Sapienza _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Ms. Lisa Lazar Linda Subich, Ph.D. _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Sandra Stansbery-Buckland, Ph.D. Chand Midha, Ph.D. _________________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT Due to a change in purpose and structure of haute couture shows in the 1970s, the vision of couture shows as performance art was born. Through investigation of the elements of performance art, as well as its functions and characteristics, this study intends to determine how modern haute couture fashion shows relate to performance art and can operate under the definition of performance art. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee––James Slowiak, Sandra Stansbery Buckland and Lisa Lazar for their time during the completion of this thesis. It is something that could not have been accomplished without your help. A special thank you to my loving family and friends for their constant support -

SWART, RENSKA L." 12/06/2016 Matches 149

Collection Contains text "SWART, RENSKA L." 12/06/2016 Matches 149 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Title/Description Date Status Home Location O 0063.001.0001.008 PLAIN TALK TICKET 1892 OK MCHS Building Ticket Ticket to a Y.M.C.A. program entitled "Plain Talk, No. 5" with Dr. William M. Welch on the subject of "The Prevention of Contagion." The program was held Thursday, October 27, 1892 at the Central Branch of the YMCA at 15th and Chestnut Street in what appears to be Philadelphia O 0063.001.0002.012 1931 OK MCHS Building Guard, Lingerie Safety pin with chain and snap. On Original marketing card with printed description and instructions. Used to hold up lingerie shoulder straps. Maker: Kantslip Manufacturing Co., Pittsburgh, PA copyright date 1931 O 0063.001.0002.013 OK MCHS Building Case, Eyeglass Brown leather case for eyeglasses. Stamped or pressed trim design. Material has imitation "cracked-leather" pattern. Snap closure, sewn construction. Name inside flap: L. F. Cronmiller 1760 S. Winter St. Salem, OR O 0063.001.0002.018 OK MCHS Building Massager, Scalp Red Rubber disc with knob-shaped handle in center of one side and numerous "teeth" on other side. Label molded into knob side. "Fitch shampoo dissolves dandruff, Fitch brush stimulates circulation 50 cents Massage Brush." 2 1/8" H x 3 1/2" dia. Maker Fitch's. place and date unmarked Page 1 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Title/Description Date Status Home Location O 0063.001.0002.034 OK MCHS Building Purse, Change Folding leather coin purse with push-tab latch. Brown leather with raised pattern. -

By ROBERT MOSES an American Builder of Today Looks Back at a Parisian Pred- Ecessor and Draws Some Conclusions for Post-War Rebuilding of Cities

\ by ROBERT MOSES An American builder of today looks back at a Parisian pred- ecessor and draws some conclusions for post-war rebuilding of cities. Author of th;~~Ii:~ ~~~k ~:stP~~~ :~~~tq~arr! cjt; I of New }!;rk, Robert the;reat M;;; ;pM;;;V;';;b ;;;i1.;;;;; 01 • Baron who rebuilt ParisM grand scale, both good qualities and faults. His dictatorial Although Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann belongs to the talents enabled him to accomplish a vast amount of work " Paris of the last century, his story is so modern and its in an incredibly short time, but they also made him many implications and lessons for us so obvious that even those enemies, for he was in the habit of riding roughshod over who do not realize that there were planners before we had planning commissions, should pause to examine this histo~ic all opposition. He had studied law and music, and had served in various figure in the modernization of cities, learn a few home truths civil service capacities during the Bourgeois Monarchy and the from what happened to him. Second Republic, and his skill in manipulating public opinion Baron Haussmann has been described as a "Brawny Alsa- in the plebiscite brought him recognition. In 1853 he was re- tian, a talker and an epicure, an ogre for work, despotic, warded by being called to Paris and given the post of .Prefect insolent, confident, full of initiative and daring, and caring of the Seine which he was to hold until January 1, 1870. hot a straw for legality." Everything about him was on a 57 19.4 2 Key to places numbered on plan which are A-Place and Tour St·Jacques B-Rue de mentioned in the text or illustrated. -

Magical Clothing Fo R Discerning Adventurers

Magical Clothing fo r Discerning Adventurers Anja Svare Sample file Introduction Table of Contents I really like making magic items. General Clothing 3 Now, there’s nothing wrong with how 5e presents the majority of magic items. But the tend to get a little stale. Potions are all essentially the same, scrolls don’t really have much interest Outerwear 6 other than what spell they contain, you’ve got a few interesting things that aren’t weapons or armor, but that’s about it. Most of those will either break a game because of their power, or Headwear 12 they should require a massive quest of campaign-level, world- spanning heroics to obtain. There just aren’t a lot of items that everyday adventurers want, Footwear 14 that won’t break the bank so to speak, and are things that are actually useful. Everybody wears clothes (I don’t want to think about nude D&D), and everybody loves magic items for their Accessories 16 character.. Combining the two seemed like a good idea, but I didn’t want Special Orders 20 to go with just pants, shirts, etc. I scoured the internet for medieval period clothing, and narrowed down a list of items that were common across a wide range of times and places throughout Europe during the Middle Ages. Now, I did come Glossary 22 across some interesting clothing items that fell outside that range or geography, and a few are included here. None of the items presented here are gender specific. I intentionally left any mention of that out of each item. -

Cu/Fh 220 Art, Design & Fashion in France

CU/FH 220 ART, DESIGN & FASHION IN FRANCE IES Abroad Paris BIA DESCRIPTION: The course aims to enrich students’ general knowledge of the fields of art and fashion over the past century. Additionally we will work on key concepts in fashion advertising, by acquiring a base in the history of fashion and in the evolution of technics in fashion marketing throughout the twentieth century. Upon completion of this course, students will be able to anticipate trends. Furthermore, this course will allow students the opportunity to develop their creativity in the field of communication. CREDITS: 3 credits CONTACT HOURS: 45 hours LANGUAGE OF INSTRUCTION: English PREREQUISITES: None METHOD OF PRESENTATION: • Lecture • Class discussion REQUIRED WORK AND FORM OF ASSESSMENT: • Course participation - 10% • Short Quizzes - 30% • Midterm Exam - 30% • Final Exam – 30% Course Participation A short daily quiz will be given at the beginning of each class. Midterm Exam The Midterm will be a written exam given in class on Monday, October 17th, which will last for 1.5 hours. Final Exam The final exam will be an analysis of a fashion marketing campaign, which will last 1.5 hours. For example the movie "Reincarnation" made by made by Karl Lagerfeld, and exercises on notions mentioned in the courses. LEARNING OUTCOMES: By the end of the course students will be able to: • Know the major players in the fashion industry. • Articulate the main steps in the evolution of fashion advertising • Identify major actors in the world of fashion marketing and important new trends in the field. • Analyze fashion with appropriate technical vocabulary • Identify principal periods in the history of fashion ATTENDANCE POLICY: Since IES BIA courses are designed to take advantage of the unique contribution of the instructor and since the lecture/discussion format is regarded as the primary mode of instruction, regular class attendance is mandatory. -

The Evolution of Fashion

^ jmnJinnjiTLrifiriniin/uuinjirirLnnnjmA^^ iJTJinjinnjiruxnjiJTJTJifij^^ LIBRARY THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA BARBARA FROM THE LIBRARY OF F. VON BOSCHAN X-K^IC^I Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/evolutionoffashiOOgardiala I Hhe Sbolution of ifashion BY FLORENCE MARY GARDINER Author of ^'Furnishings and Fittings for Every Home" ^^ About Gipsies," SIR ROBERT BRUCE COTTON. THE COTTON PRESS, Granvii^le House, Arundel Street, VV-C- TO FRANCES EVELYN, Countess of Warwick, whose enthusiastic and kindly interest in all movements calculated to benefit women is unsurpassed, This Volume, by special permission, is respectfully dedicated, BY THE AUTHOR. in the year of Her Majesty Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, 1897. I I I PREFACE. T N compiling this volume on Costume (portions of which originally appeared in the Lndgate Ilhistrated Magazine, under the editorship of Mr. A. J. Bowden), I desire to acknowledge the valuable assistance I have received from sources not usually available to the public ; also my indebtedness to the following authors, from whose works I have quoted : —Mr. Beck, Mr. R. Davey, Mr. E. Rimmel, Mr. Knight, and the late Mr. J. R. Planchd. I also take this opportunity of thanking Messrs, Liberty and Co., Messrs. Jay, Messrs. E. R, Garrould, Messrs. Walery, Mr. Box, and others, who have offered me special facilities for consulting drawings, engravings, &c., in their possession, many of which they have courteously allowed me to reproduce, by the aid of Miss Juh'et Hensman, and other artists. The book lays no claim to being a technical treatise on a subject which is practically inexhaustible, but has been written with the intention of bringing before the general public in a popular manner circumstances which have influenced in a marked degree the wearing apparel of the British Nation.