Reparations, Rhetoric, and Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Mcpherson Leader Entry by Michael Fitzgerald

Charles McPherson Leader Entry by Michael Fitzgerald Generated on Sun, Oct 02, 2011 Date: November 20, 1964 Location: Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ Label: Prestige Charles McPherson (ldr), Charles McPherson (as), Carmell Jones (t), Barry Harris (p), Nelson Boyd (b), Albert 'Tootie' Heath (d) a. a-01 Hot House - 7:43 (Tadd Dameron) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! b. a-02 Nostalgia - 5:24 (Theodore 'Fats' Navarro) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! c. a-03 Passport [tune Y] - 6:55 (Charlie Parker) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! d. b-01 Wail - 6:04 (Bud Powell) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! e. b-02 Embraceable You - 7:39 (George Gershwin, Ira Gershwin) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! f. b-03 Si Si - 5:50 (Charlie Parker) Prestige LP 12": PR 7359 — Bebop Revisited! g. If I Loved You - 6:17 (Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II) All titles on: Original Jazz Classics CD: OJCCD 710-2 — Bebop Revisited! (1992) Carmell Jones (t) on a-d, f-g. Passport listed as "Variations On A Blues By Bird". This is the rarer of the two Parker compositions titled "Passport". Date: August 6, 1965 Location: Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ Label: Prestige Charles McPherson (ldr), Charles McPherson (as), Clifford Jordan (ts), Barry Harris (p), George Tucker (b), Alan Dawson (d) a. a-01 Eronel - 7:03 (Thelonious Monk, Sadik Hakim, Sahib Shihab) b. a-02 In A Sentimental Mood - 7:57 (Duke Ellington, Manny Kurtz, Irving Mills) c. a-03 Chasin' The Bird - 7:08 (Charlie Parker) d. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

À Ne Pas Manquer/ Not to Be Missedjuillet/Août

sm26-8_BI_p01_coverV1_sm26-8BI 2021-07-13 5:25 AM Page 1 sm26-8_BI_p02_ADS_Production10_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2021-07-12 11:18 PM Page 1 sm26-8_BI_p03_ADS_sm26-5_BI_pXX 2021-07-12 11:24 PM Page 1 JUILLET/AOÛT À NE PAS MANQUER/ NOT TO BE MISSED JULY/AUGUST GRATUIT ET OUVERT À TOUT LE MONDE ! e 3 ÉDITION OCTOBRE 2021 ACTIVITÉS VARIÉES DANS LE ADVERSTISE VILLAGE ET LE QUARTIER LATIN your event here! NOUVELLE PROGRAMMATION EXTÉRIEURE CETTE ANNÉE, DÉTAILS À VENIR POUR DEVENIR PARTENAIRE OFFICIEL, Annoncez votre événement ici! OU ORGANISME PARTICIPANT, OU BÉNÉVOLE : 2021-22 • Canada www.mySCENA.org partenaires en date d’AVRIL 2021 6-22 août 2021 SERVICE À LA FAMILLE CHINOISE DU GRAND MONTRÉAL Opéra RigOlettO 22 AOÛT - graphisme et vidéo sur notre chaîne Youtube multimédia et Facebook Live ÉVÉNEMENT COMMUNAUTAIRE /italfestMTL ORGANISÉ PAR italfestmtl.ca sm26-8_BI_p04_TOCv3web_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2021-07-13 10:16 PM Page 4 Sommaire/Contents LSM VOL 26-8 Juillet-Août 2021 July-Aug 6 Éditorial / Editorial 8 Festivals d’été / Summer Festivals 10 Brott Music 10 Elora Festivals 11 Festival de Lanaudière 11 Festival d’Opéra de Québec 12 Concerts au BIC 12 Carrefour d’accordéon 14 Industry News 16 Jeanne Lamon 18 LMMC 20 Orchestre classique de Montréal 22 Albertine en cinq temps - L’opéra 26 Albertine : Catherine Major 28 Albertine : Michel Tremblay 30 Jazz : Projets spéciaux 31 Jazz : Au rayon du disque 31 Audio 32 Did you know? 33 Nouveautés / New Releases 34 Critiques / Reviews CATHERINE MAJOR 38 Erlkönig 26 42 Calendrier régional / Regional Calendar RÉDACTEURS FONDATEURS / ÉDITEUR / PUBLISHER PUBLICITÉ / ADVERTISING LA SCENA MUSICALE and reviews as well as calendars. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Joe Henderson: a Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 12-5-2016 Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations © 2016 JOEL GEOFFREY HARRIS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School JOE HENDERSON: A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY OF HIS LIFE AND CAREER A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Joel Geoffrey Harris College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Jazz Studies December 2016 This Dissertation by: Joel Geoffrey Harris Entitled: Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in the College of Performing and Visual Arts in the School of Music, Program of Jazz Studies Accepted by the Doctoral Committee __________________________________________________ H. David Caffey, M.M., Research Advisor __________________________________________________ Jim White, M.M., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Socrates Garcia, D.A., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Stephen Luttmann, M.L.S., M.A., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense ________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School _______________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and International Admissions ABSTRACT Harris, Joel. Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career. Published Doctor of Arts dissertation, University of Northern Colorado, December 2016. This study provides an overview of the life and career of Joe Henderson, who was a unique presence within the jazz musical landscape. It provides detailed biographical information, as well as discographical information and the appropriate context for Henderson’s two-hundred sixty-seven recordings. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Max Roach and M'boom

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Max Roach and M’Boom: Diasporic Soundings in American Percussion Music A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements of the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Contemporary Music Performance by Sean Leah Bowden Committee in charge: Professor Steven Schick, Chair Professor Amy Cimini Professor Anthony Davis Professor Stephanie Richards Professor Emily Roxworthy 2018 The Dissertation of Sean Leah Bowden is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California San Diego 2018 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………………… iv Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………. v Vita…………………………………………………………………………………………………. vi Abstract of the Dissertation……………………………………………………………………… vii Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………... 1 Jazz Drumming: Possibilities, Limitations……………………………………………………… 7 Spatial Eruptions in the Space Age……………………………………………………. 9 Freedom From/ Freedom To: The Multiple Avant-Gardes of 1970s Jazz………………….. 20 Searching for the Sound of Diaspora………………………………………………………….. -

Dolly HAAS: Bobby HACKETT

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Dolly HAAS: Dolly Haas und Paul Godwin Orchester; recorded September 1932 in Berlin 108045 ACH WIE IST DAS LEBEN SCHÖN 2.46 4951 Gram 24764 aus dem Tonfilm "Scampolo" ------------------------------------------ Bobby HACKETT: Bobby Hackett -co; George Brunies -tb; Pee Wee Russell -cl,ts; Bernie Billings -ts; Dave Bowman - p; Eddie Condon -g; Clyde Newcomb -b; Johnny Blowers -d; Lola Bard -vo; recorded February 16, 1938 in New York 57864 YOU, YOU AND ESPECIALLY YOU 2.57 M754-1 Voc/Okeh 4142 57865 IF DREAMS COME TRUE 2.52 M755-1 Voc/Okeh 4047 57866 THAT DA-DA STRAIN 2.44 M757-1 Voc/Okeh 4142 57867 AT THE JAZZ BAND BALL 2.34 M756-1 Voc/Okeh 4047 "The Saturday Night Swing Club is On The Air" Bobby Hackett -co; Brad Gowans -vtb; Pee Wee Russell -cl; Ernie Caceres -bs; Dave Bowman -p; Eddie Condon -g; Clyde Newcomb -b; George Wettling -d; recorded June 25, 1938 in Broadcast, New York 70029 AT THE JAZZ BAND BALL 3.06 Fanfare LP17-117 Bobby Hackett -co; Brad Gowans -vtb,as; Pee Wee Russell -cl; Ernie Caceres -bs; Dave Bowman - p; Eddie Condon -g; Clyde Newcomb -b; Andy Picard -d; Linda Keene -vo; recorded November 04, 1938 in New York 57860 GHOST OF A CHANCE 2.55 M917-1 Voc/Okeh 4499 57861 POOR BUTTERFLY 2.22 M918-1 --- 57862 BLUE AND DISILLUSIONED 2.25 M916-1 Voc/Okeh 4565 57863 DOIN' THE NEW LOW-DOWN 2.29 M919-1 --- "Bobby Hackett and his Rhythm Cats" Bobby Hackett -co; Brad Gowans -

South African Jazz and Exile in the 1960S: Theories, Discourses and Lived Experiences

South African Jazz and Exile in the 1960s: Theories, Discourses and Lived Experiences Stephanie Vos In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music Royal Holloway, University of London September 2015 Declaration of Authorship I, Stephanie Vos, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 28 August 2016 2 Abstract This thesis presents an inquiry into the discursive construction of South African exile in jazz practices during the 1960s. Focusing on the decade in which exile coalesced for the first generation of musicians who escaped the strictures of South Africa’s apartheid regime, I argue that a lingering sense of connection (as opposed to rift) produces the contrapuntal awareness that Edward Said ascribes to exile. This thesis therefore advances a relational approach to the study of exile: drawing on archival research, music analysis, ethnography, critical theory and historiography, I suggest how musicians’ sense of exile continuously emerged through a range of discourses that contributed to its meanings and connotations at different points in time. The first two chapters situate South African exile within broader contexts of displacement. I consider how exile built on earlier forms of migration in South Africa through the analyses of three ‘train songs’, and developed in dialogue with the African diaspora through a close reading of Edward Said’s theorization of exile and Avtar Brah’s theorization of diaspora. A case study of the Transcription Centre in London, which hosted the South African exiles Dorothy Masuku, Abdullah Ibrahim, and the Blue Notes in 1965, revisits the connection between exile and politics, broadening it beyond the usual national paradigm of apartheid politics to the international arena of Cold War politics. -

Suggested Listening - Jazz Artists 1

SUGGESTED LISTENING - JAZZ ARTISTS 1. TRUMPET - Nat Adderley, Louis Armstrong, Chet Baker, Terrance Blanchard, Lester, Bowie, Randy Brecker, Clifford Brown, Don Cherry, Buck Clayton, Johnny Coles, Miles Davis, Kevin Dean, Kenny Dorham, Dave Douglas, Harry Edison, Roy Eldridge, Art Farmer, Dizzy Gillespie, Bobby Hackett, Tim Hagans, Roy Hargrove, Phillip Harper,Tom Harrell, Eddie Henderson, Terumaso Hino, Freddie Hubbard, Ingrid Jensen, Thad Jones, Booker Little, Joe Magnarelli, John McNeil, Wynton Marsalis, John Marshall, Blue Mitchell, Lee Morgan, Fats Navarro, Nicholas Payton, Barry Ries, Wallace Roney, Jim Rotondi, Carl Saunders, Woody Shaw, Bobby Shew, John Swana, Clark Terry, Scott Wendholt, Kenny Wheeler 2. SOPRANO SAX - Sidney Bechet, Jane Ira Bloom, John Coltrane, Joe Farrell, Steve Grossman, Christine Jensen, David Liebman, Steve Lacy, Chris Potter, Wayne Shorter 3. ALTO SAX - Cannonball Adderley, Craig Bailey, Gary Bartz, Arthur Blythe, Richie Cole, Ornette Coleman, Steve Coleman, Paul Desmond, Eric Dolphy, Lou Donaldson, Paquito D’Rivera, Kenny Garrett, Herb Geller, Bunky Green, Jimmy Greene, Antonio Hart, John Jenkins, Christine Jensen, Eric Kloss, Lee Konitz, Charlie Mariano, Jackie McLean, Roscoe Mitchell, Frank Morgan, Lanny Morgan, Lennie Niehaus, Greg Osby, Charlie Parker, Art Pepper, Bud Shank, Steve Slagel, Jim Snidero, James Spaulding, Sonny Stitt, Bobby Watson, Steve Wilson, Phil Woods, John Zorn 4. TENOR SAX - George Adams, Eric Alexander, Gene Ammons, Bob Berg, Jerry Bergonzi, Don Braden, Michael Brecker, Gary Campbell, -

JTM1711 Insidecombo 170920.Indd

On May 31, drummer Louis Hayes celebrated his 80th birthday and a new album at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola in New York, surrounded by friends, collaborators and acolytes, including drummers Michael Carvin, Nasheet Waits and Eric McPherson, and trumpeters Jimmy Owens and Jeremy Pelt, the latter of whom sat in. Another presence loomed large: pianist-composer Horace Silver, the subject of Hayes’ recent Blue Note debut, Serenade for Horace, a heartfelt tribute to the man who gave Hayes his start in 1956 with “Señor Blues.” It was the beginning of a three-year col- laboration that helped codify both hard bop and the Rudy Van Gelder sound over five albums. Hayes left Silver in 1959 to join the Cannonball Adderley Quintet, but the two re- mained close until the hard-bop progenitor’s passing in 2014. Stints followed with Oscar Peterson, the Louis Hayes-Woody Shaw Quintet, Stan Getz, McCoy Tyner and the Can- nonball Legacy Band, which Hayes leads. Throughout his career he’s solidified a place as one of jazz’s most soulfully swinging drummers, and become a cornerstone of the legacy of Detroit-born percussionists that includes Elvin Jones, Roy Brooks, Frank Gant and Oliver Jackson, and extends forward to Gerald Cleaver. At Dizzy’s, Hayes used his hyper-responsive left hand to goose the soloists in his sextet while keeping the fugitive spirit alive with his right on the ride cymbal. His approach seemed to declare the ensemble’s m.o., which balanced rhythmic ferocity and harmonic adventurousness with a reverence for the Silver sprezzatura. -

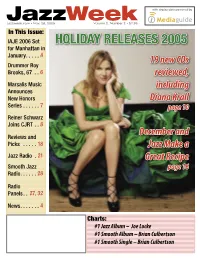

Performs the Baby Face Song- Book (Rendezvous) Was the Top Gainer on the Album Chart

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • Nov. 28, 2005 Volume 2, Number 2 • $7.95 In This Issue: IAJE 2006 Set HOLIDAY RELEASES 2005 for Manhattan in January. 4 19 new CDs Drummer Roy Brooks, 67 . 6 reviewed, Marsalis Music including Announces New Honors Diana Krall Series . 7 page 10 Reiner Schwarz Joins CJRT . 8 December and Reviews and Picks . 18 Jazz Make a Jazz Radio . 21 Great Recipe Smooth Jazz page 16 Radio. 28 Radio Panels. 27, 32 News. 4 Charts: #1 Jazz Album – Joe Locke #1 Smooth Album – Brian Culbertson #1 Smooth Single – Brian Culbertson JazzWeek This Week EDITOR/PUBLISHER Ed Trefzger MUSIC EDITOR enjoy hearing Christmas music – once it’s close to the Tad Hendrickson holiday. Around the country there are stations already CONTRIBUTING EDITORS I playing all holiday music, and they’ve been doing it for Keith Zimmerman weeks, in some cases. Now that Thanksgiving is past us, Kent Zimmerman CONTRIBUTING WRITER/ it’s time to start including some music of the season for PHOTOGRAPHER many stations, and there’s a pretty nice selection of new Tom Mallison holiday releases this year. We’ve got our capsule reviews PHOTOGRAPHY Barry Solof of 19 of them starting on page 10. And if you’re looking for more ideas about how to program music of the season Founding Publisher: Tony Gasparre on your station, check out Tom Mallison’s second annual ADVERTISING: Devon Murphy Call (866) 453-6401 ext. 3 or look at holiday favorites on page 16. email: [email protected] SUBSCRIPTIONS: ••• Free to qualified applicants Premium subscription: $149.00 per year, w/ Industry Access: $249.00 per year Qualified people in the industry are now able to sign To subscribe using Visa/MC/Discover/ AMEX/PayPal go to: up to receive this publication free of charge, and we’ve had http://www.jazzweek.com/account/ a lot of people take advantage of this already. -

Silver,Let'sgettonitty

ROTH FAMILY FOUNDATION Music in America Imprint Michael P. Roth and Sukey Garcetti have endowed this imprint to honor the memory of their parents, Julia and Harry Roth, whose deep love of music they wish to share with others. The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the Music in America Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Foundation, which is supported by a major gift from Sukey and Gil Garcetti, Michael Roth, and the Roth Family Foundation. LET’S GET TO THE NITTY GRITTY LET’S GET TO THE NITTY GRITTY THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF HORACE SILVER HORACE SILVER Edited, with Afterword, by Phil Pastras Foreword by Joe Zawinul University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2006 by The Regents of the University of California Excerpts from “How Calmly Does the Orange Branch,” by Tennessee Williams, from The Collected Poems of Tennessee Williams, copyright © 1925, 1926, 1932, 1933, 1935, 1936, 1937, 1938, 1942, 1944, 1947, 1948, 1949, 1950, 1952, 1956, 1960, 1961, 1963, 1964, 1971, 1975, 1977, 1978, 1979, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1991, 1995, 2002 by The University of the South. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.