Larry Gray Interview Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BUCKEYE COUNTRY SUPERFEST Presented by Budweiser KENNY

BUCKEYE COUNTRY SUPERFEST presented by Budweiser Saturday, June 20, 2020 at Ohio Stadium KENNY CHESNEY FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE KANE BROWN * BRETT YOUNG * GABBY BARRETT WITH TYLER RICH September 24, 2019 (Columbus, Ohio) – Just announced, “The King of the Road”, Kenny Chesney will headline Buckeye Country Superfest 2020 presented by Budweiser. Chesney will be joined by Multi-platinum duo Florida Georgia Line, RIAA Gold-Certified Kane Brown, ASCAP’s 2018 Country Songwriter-Artist of the Year Brett Young, Radio Disney’s “Next Big Thing” Gabby Barrett, plus 2018 CMT Listen Up Artist Tyler Rich at iconic Ohio Stadium in Columbus, Ohio. “To say we are stoked to share the stage with the king of island vibes himself is an understatement,” shares FGL’s Brian Kelley. “We’ve been huge fans of Kenny for a long time and this is definitely going to be a party!” “We’ve been lucky enough to play several stadiums nationwide, but this will be our first time doing it in Ohio,” adds FGL’s Tyler Hubbard. “Each one has its own iconic magic and we can’t wait to see the Buckeye fans out in full force!” When asked about coming to Buckeye Country Superfest, Brett Young said “Performing in a football stadium in the summertime for thousands of hyped up country music fans will always be pretty surreal and special. Ohio, my calendar is already circled for this one!” 2020 will mark the fifth year Ohio Stadium opens its gates for Buckeye Country Superfest. An enthusiastic crowd of 55,402 country music fans two-stepped and sang along at Buckeye Country Superfest 2019, setting the single day attendance record for the festival. -

A Semantic Analysis of Non Literal Meaning a Thesis By

THE SADNESS PORTRAYED IN TAYLOR SWIFT’S SELECTED SONGS: A SEMANTIC ANALYSIS OF NON LITERAL MEANING A THESIS BY WINDI RIAHNA KELIAT REG. NO. 140705167 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA THE SADNESS PORTRAYED IN TAYLOR SWIFT’S SELECTED SONGS: A SEMANTIC ANALYSIS OF NON LITERAL A THESIS BY WINDI RIAHNA KELIAT REG. NO. 140705167 SUPERVISOR CO-SUPERVISOR Dr. Deliana, M.Hum. Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A, Ph. D. NIP. 19571117 198303 2 002 NIP. 19750209 200812 1 002 Submitted to Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Medan i n partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from Department of English. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Approved by the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of Sumatera Utara (USU) Medan as thesis for The Sarjana Sastra Examination. Head Secretary Prof. T. Silvana Sinar, M. A., Ph. D. Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A., Ph. D. NIP. 19540916 198003 2 003 NIP. 19750209 200812 1 002 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Accepted by the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara, Medan. The examination is held in Department of English Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara on April 12th, 2019 Dean of Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Dr. Budi Agustono, M.S. NIP. 19600805 198703 1 001 Board of Examiners Prof. T. -

Time's Sketchy Rules

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2016 Time's Sketchy Rules Nadirah Baarh How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/652 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Time’s Sketchy Rules Nadirah Baarh Pamela Laskin 11/28/2016 [email protected] Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts of the City College of the City University of New York. Baarh 1 Time’s Sketchy Rules Prologue What is time anyway? Where does it begin and when does it end? Is it linear and bendy like those plastic rulers we used to use in math class? Does it stop sometimes, like those old clocks that tick tick tick all day long, but one day, in a sudden twist of fate, you look at it and it’s not moving? And you freak because you don’t know what time it is. All of a sudden, you’re living in this strange limbo moment where time isn’t being measured, and well, that just won’t do. We need measurement. We need time. In the smaller than life, not even big enough to be microscopic, world of quantum physics measurement is quantified. If you touch something, notice it, try to measure it, you instantly change it. Everything is in a state of superposition—where two opposite things, two completely opposite things, somehow manage to be equally true at the same time. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Popular Wedding Covers (346)

The Atlanta Wedding Band is proud to have performed over 100 weddings since the beginning of 2011. We have the distinct honor of being a 5 star band on www.gigmasters.com, not only that, but every client that has booked us through that site has given us 5 out of 5! Atlanta Wedding Band 1418 Dresden Drive Unit 365, Atlanta, Georgia, 30319, United States. 404-272-0337 Popular Wedding Covers (346) For an all inclusive list (700+), scroll further down! Motown/R&B/Funk/Dance (53) Al Green Let’s Stay Together Aretha Franklin Ain’t No Mountain High Enough BeeGees Stayin Alive Ben E. King Stand by Me Beyonce Knowles Irreplaceable Bill Withers Ain’t No Sunshine Lean On Me Black Eyed Peas I Got a Feeling Bruno Mars (Mark Ronson) Marry You Uptown Funk Cee-Lo Green Forget You Chubby Checker The Twist The Commodores Brick House The Contours Do You Love Me Cupid Cupid Shuffle Dexy’s Midnight Runners Come on Eileen Earth Wind and Fire September The Foundations Build me Up Buttercup The Four Tops I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar pie, Honey Bunch) Hall and Oates You Make My Dreams The Isley Brothers Shout Jackson 5 ABC I Want You Back James Brown I Feel Good Jason Derulo It Girl Want to Want Me Kenny Loggins Footloose King Harvest Dancing in the Moonlight Kool and the Gang Celebration Lionel Ritchie All Night Long Louis Armstrong What a Wonderful World Marvin Gaye How Sweet It Is Let’s Get it On Sexual Healing Michael Jackson Billie Jean Man in the Mirror Otis Redding Sittin on the Dock of the Bay Outkast Hey Ya Sorry Ms. -

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik. Bobby Charles was born Robert Charles Guidry on 21st February 1938 in Abbeville, Louisiana. A native Cajun himself, he recalled that his life “changed for ever” when he re-tuned his parents’ radio set from a local Cajun station to one playing records by Fats Domino. Most successful as a songwriter, he is regarded as one of the founding fathers of swamp pop. His own vocal style was laidback and drawling. His biggest successes were songs other artists covered, such as ‘See You Later Alligator’ by Bill Haley & His Comets; ‘Walking To New Orleans’ by Fats Domino – with whom he recorded a duet of the same song in the 1990s – and ‘(I Don’t Know Why) But I Do’ by Clarence “Frogman” Henry. It allowed him to live off the songwriting royalties for the rest of his life! Two other well-known compositions are ‘The Jealous Kind’, recorded by Joe Cocker, and ‘Tennessee Blues’ which Kris Kristofferson committed to record. Disenchanted with the music business, Bobby disappeared from the music scene in the mid-1960s but returned in 1972 with a self-titled album on the Bearsville label on which he was accompanied by Rick Danko and several other members of the Band and Dr John. Bobby later made a rare live appearance as a guest singer on stage at The Last Waltz, the 1976 farewell concert of the Band, although his contribution was cut from Martin Scorsese’s film of the event. Bobby Charles returned to the studio in later years, recording a European-only album called Clean Water in 1987. -

A Piece of History

A Piece of History Theirs is one of the most distinctive and recognizable sounds in the music industry. The four-part harmonies and upbeat songs of The Oak Ridge Boys have spawned dozens of Country hits and a Number One Pop smash, earned them Grammy, Dove, CMA, and ACM awards and garnered a host of other industry and fan accolades. Every time they step before an audience, the Oaks bring four decades of charted singles, and 50 years of tradition, to a stage show widely acknowledged as among the most exciting anywhere. And each remains as enthusiastic about the process as they have ever been. “When I go on stage, I get the same feeling I had the first time I sang with The Oak Ridge Boys,” says lead singer Duane Allen. “This is the only job I've ever wanted to have.” “Like everyone else in the group,” adds bass singer extraordinaire, Richard Sterban, “I was a fan of the Oaks before I became a member. I’m still a fan of the group today. Being in The Oak Ridge Boys is the fulfillment of a lifelong dream.” The two, along with tenor Joe Bonsall and baritone William Lee Golden, comprise one of Country's truly legendary acts. Their string of hits includes the Country-Pop chart-topper Elvira, as well as Bobbie Sue, Dream On, Thank God For Kids, American Made, I Guess It Never Hurts To Hurt Sometimes, Fancy Free, Gonna Take A Lot Of River and many others. In 2009, they covered a White Stripes song, receiving accolades from Rock reviewers. -

November 1934

VOL. V - NOVEMBER I934 - No. ZI The Netherlands East Indies MGon of The Chrktian and Missionary A!l;ance Address: Lagc~vq81. Makassar. CeIeL. N.E.I. THE PIONEER i :, NOTHING IS TOO HARD FOR JESUS Dr. A. B. Simpson Oft there comes a wondrous message When my hopes are growing dim. I can hear it through the darkness, Like some sweet and far-off hymn. Chorus : Nothing is too hard for Jesus. No man can work like Him : Nothing is too hard for Jesus. No man can work like Him. When my frame is worn with sickness, And with tears my eyelids swim. 1 can hear the promise ringing, Like some sweet and heav'nly hymn. When my way is closed with darkness. And my foes are fierce and grim. Still it sings above the conflict. Like some glad, victorious hymn. When my heart is crushed with anguish, And the waters reach the brim. Faith can hear the mighty chorus. Like some mighty battle-hymn. Let us claim the gracious promise, Let us light the torches dim, Let us join the mighty chorus. Let us swell the glorious hymn. L THE PIONEER EDITORIAL THANKSGIVING NUMBER Every number of The Pioneer ought to be called a Thanks-. giving Number. How much we have for which to be thank- ful ! The special thought in mind in calling this number a Thanksgiving Number, apart from the approaching Thanks-. giving Day, is that since the issue of our last number of The Pioneer. over a thousand more Dyaks have been baptized. As the reports came to us from Borneo. -

Music Therapy Master Song Resource List

University of Kansas Music Therapy Song Repertoire Resource List Spring 2021 The KU music therapy song repertoire resource list acts as a reference for music therapy students as they work to develop a diverse repertoire of songs for use in their musical, pre-clinical, and clinical work. As such, it is a both a document of important songs that have historically been used in music therapy processes, and a living, breathing document that will be updated intermittently to maintain the dynamic of new musics. Songs are categorized and divided into music genres. Genres provide some level of diversity. Current genres in the book are provided as a general list on page 2, and then each genre is presented alphabetically, with songs in each genre also presented alphabetically. This approach helps to make finding songs easier. Some songs will be cross-referenced. Each song will include either an original artist or the song’s author (or both), as well as the year the song was written. This list can help students learn more songs, not only for singing and accompaniment purposes, but also for using recordings of songs when appropriate. Students are strongly encouraged to locate and listen to original recordings of songs to help their learning processes. Original notation in lead sheets is also helpful, especially for students that excel in reading. A good ear and solid music reading skills help for music therapists to be efficient in their learning of new songs. Also, looking up the history of a song helps a clinician make important decisions on how the music may connect with a client, increasing the potential for its effective use. -

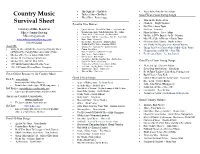

Cheat Sheet 2011.Pdf

• This Night Life - Clint Black • What’s A Guy Gotta Do – Joe Nichols Country Music • Tuckered Out – Clint Black Good West-Coast Swing Songs • Wheel Hoss - Ricky Scaggs • Turn On The Radio - Reba Survival Sheet Favorite Line Dances • Claudette – Dwight Yoakam • Kiss This – Aaron Tippin Courtesy of Mike Bendavid • Quarter After One – Need You Now - Lady Antebellum • No News – Lonestar Mike's Country Dancing • Bodonkadonk – Honky Tonk Bodonkadonk - Trace Adkins • Marry for Money – Trace Adkins • Chicken Fried – Chicken Fried – Zac Brown Band • My Give A D***'s Busted - Jo Dee Messina [email protected] • Come Dance With Me – Come Dance With Me – Nancy Hays • www.mikescountrydancing.com • Dizzy – Dizzy – Scooter Lee Man! I Feel Like A Woman – Shania Twain • • 818-905-6644 Electric Slide – Fast As You – Dwight Yoakam Play Something Country - Brooks & Dunn • Gotta Get To You – George Strait • She Thinks My Tractor's Sexy - Kenny Chesney About Mike • Key Lime Pie – Key Lime Pie – Kenny Chesney • Things That Never Cross A Man’s Mind – Kellie Pickler • Voting Member of Both The Academy of Country Music • Cruisin– Beach Boys • Cleopatra Queen of DeNile – Pam Tillis (ACM) and The Country Music Association (CMA) • Rock It - Baby Likes To Rock It – Tractors • Rose Garden – Martina McBride • Fresh Coat of Paint – Lee Roy Parnell • Member of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) • • Kill The Spider– Brad Paisley Member DJ Chat Country Hall of Fame • Sand & Sea – Laid Back and Low Key – Alan Jackson • Member NTA, ASCAP, BMI, ADJA, • Suds In The Bucket - Sara -

Reflections on a Pandemic Thoughts, Considerations, Poems, Philosophies & Understandings

REFLECTIONS ON A PANDEMIC THOUGHTS, CONSIDERATIONS, POEMS, PHILOSOPHIES & UNDERSTANDINGS NOELLE BIEHLE intin awingI 1 Open with INTRODUCTION The coronavirus pandemic has changed us all. No one could have predicted the ways in which we would become different, in our outlooks, our physical living conditions, and in the ways we connect (or don’t) with each other. Towards the end of April, I sent our seventh graders a collection of questions, created by the organization Facing History and Ourselves. The same organization created an activity called “Toolbox for Care,” in which students we asked to put together a collection of items for both self-care and care for others. What follows is their thoughts and ideas during the time of quarantine. Thank you, Noelle, for your breathtaking art! Frieda Katz At this time where there is a worldwide pandemic spreading fear and anguish across the globe, pain is unavoidable. It can be the mental pain of losing a family member, friends or physical pain where the virus has gotten to you. The pain can also be subtle, such as missing friends who are trapped inside their homes like 2 yourself. This pain is a reflection of how human interaction is vital for people to survive through life. Distress can cause depression or stressing about education, work, sports or health. The corona virus has brought more stress around the world than anything else my generation has seen. The serenity of isolation, Alone on a hill of daisies, As bright as the sun blinding my eyes, Forcing them to close, and eventually relax under the heat, My feet brushing against the grass, Filled with warmth but at the same time, Swaying to the rhythm of the autumn’s breeze, If only this was real, Such peace, No wars or diseases or death, Coming from behind, And grabbing your loved ones from your shaking arms, Not looking back once too see the pain it's brought, To a broken world, Never perfect, Never will be perfect.