Pony Express National Historic Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society

Library of Congress Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society. Volume 12 COLLECTIONS OF THE MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XII. ST. PAUL, MINN. PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY. DECEMBER, 1908. No. 2 F601 .M66 2d set HARRISON & SMITH CO., PRINTERS, LITHOGRAPHERS, AND BOOKBINDERS, MINNEAPOLIS, MINN. OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY. Nathaniel P. Langford, President. William H. Lightner, Vice-President. Charles P. Noyes, Second Vice-President. Henry P. Upham, Treasurer. Warren Upham, Secretary and Librarian. David L. Kingsbury, Assistant Librarian. John Talman, Newspaper Department. COMMITTEE ON PUBLICATIONS. Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society. Volume 12 http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.0866g Library of Congress Nathaniel P. Langford. Gen. James H. Baker. Rev. Edward C. Mitchell. COMMITTEE ON OBITUARIES. Hon. Edward P. Sanborn. John A. Stees. Gen. James H. Baker. The Secretary of the Society is ex officio a member of these Committees. PREFACE. This volume comprises papers and addresses presented before this Society during the last four years, from September, 1904, and biographic memorials of its members who have died during the years 1905 to 1908. Besides the addresses here published, several others have been presented in the meetings of the Society, which are otherwise published, wholly or in part, or are expected later to form parts of more extended publications, as follows. Professor William W. Folwell, in the Council Meeting on May 14, 1906, read a paper entitled “A New View of the Sioux Treaties of 1851”; and in the Annual Meeting of the Society on January 13, 1908, he presented an address, “The Minnesota Constitutional Conventions of 1857.” These addresses are partially embodied in his admirable concise history, “Minnesota, the North Star State,” published in October, 1908, by the Houghton Mifflin Company as a volume of 382 pages in their series of American Commonwealths. -

Human Rights Brief a Legal Resource for the International Human Rights Community

Human Rights Brief A Legal Resource for the International Human Rights Community Volume 10 Issue 2 American Indian Land Rights in the Inter-American System: Dann v. United States by lnbal Sansani* On July 29, 2002, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (Commission), an organ of the Organization of American States (OAS) headquartered in Washington, D.C., released its long-awaited preliminary merits report to the public, stating that the U.S. government is violating international human rights in its treatment of Western Shoshone elders Carrie and Mary Dann. This is the first decision of the Commission, or of any international body, finding that the United States has violated the rights of American Indians. The Commission’s preliminary merits report had already been released to the parties on October 15, 2001, in response to a petition filed on April 2, 1993 by the Indian Law Resource Center (ILRC), a non-profit legal advocacy organization based in Helena, Montana. The ILRC brought the petition on behalf of the Dann sisters—American Indians, U.S. citizens, and members of the Dann Band of the Western Shoshone Nation. The petition charged the United States with illegally depriving the Dann sisters and other members of the Western Shoshone Nation of their ancestral lands. The Commission’s preliminary merits report supported the Danns’ argument that the U.S. government used illegitimate means to gain control of Western Shoshone ancestral lands through the Indian Claims Commission (ICC), a now defunct administrative tribunal established by Congress in 1946 to determine outstanding American Indian land title disputes and to award compensation for land titles that had been extinguished. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

US Postal Laws & Regulations

US Postal Laws & Regulations Brought to you by the US Postal Bulletins Consortium Year: 1940 Transportation of the mails Table Of Contents Click here to view the entire PDF Document Pages Accounts (32 pages) 151-182 Advertised (3 pages) 399-400, 419 Air mail stamps (1 page) 249 Air-mail (23 pages) 8, 11, 248-249, 709-721, 801, 841-845 Audits (2 pages) 71-72 Avis de reception (2 pages) 802, 809 Bad order (7 pages) 358, 524-527, 793-794 Blind matter (7 pages) 283, 350-354, 800 Book rate (2 pages) 290-291 Bound printed matter (1 page) 288 Boxes (18 pages) 238-242, 391-392, 439-444, 469-473 Business reply mail (2 pages) 247-248 Carriers (58 pages) 425-473, 542-550 Certificate of mailing (4 pages) 293-294, 493, 558 Circulars (1 page) 282 Closed mails (1 page) 808 COD (15 pages) 13, 536, 556-562, 565-570 Commercial papers (1 page) 800 Copyright (3 pages) 348-350 Crimes, postal (32 pages) 853-884 Customs (19 pages) 791-792, 813-829 Dead letter office (29 pages) 8, 87-88, 330, 332, 355, 366-368, 397-399, 401-402, 415-424, 492, 542, 810-812 Deliver to addressee only (6 pages) 490-491, 532, 534-535, 537 Delivery of mail (100 pages) 388-399, 425-484, 528-550, 560-562, 809-810 Delivery offices (115 pages) 377-406, 425-484, 528-550, 809-810 Demurrage (1 page) 568 Directory service (3 pages) 400, 416, 534 Distribution (5 pages) 370-374 Drop letters (3 pages) 243, 249, 401 Dutiable mail (19 pages) 791-792, 813-829 Electric cars (7 pages) 8, 698-703 Fictitious (4 pages) 333-334, 416, 418 First assistant PG (3 pages) 7-8, 201 First-class mail matter (12 -

Stephan Langton

HDBEHT W WDDDHUFF LIBRARY STEPHAN LANGTON. o o a, H z u ^-^:;v. en « ¥ -(ft G/'r-' U '.-*<-*'^f>-/ii{* STEPHAN LANGTON OR, THE DATS OF KING JOHN M. F- TUPPER, D.C.L., F.R.S., AUTHOR OF "PROVERBIAL PHILOSOPHY," "THREE HUNDRED SONNETS,' "CROCK OF GOLD," " OITHARA," "PROTESTANT BALLADS,' ETC., ETC. NEW EDITION, FRANK LASHAM, 61, HIGH STREET, GUILDFORD. OUILDFORD : ORINTED BY FRANK LA3HAM, HIGH STI;EET PREFACE. MY objects in writing " Stephan Langton " were, first to add a Dcw interest to Albury and its neighbourhood, by representing truly and historically our aspects in the rei"n of King John ; next, to bring to modem memory the grand character of a great and good Archbishop who long antedated Luther in his opposition to Popery, and who stood up for English freedom, ctilminating in Magna Charta, many centuries before these onr latter days ; thirdly, to clear my brain of numeroua fancies and picturea, aa only the writing of another book could do that. Ita aeed is truly recorded in the first chapter, as to the two stone coffins still in the chancel of St. Martha's. I began the book on November 26th, 1857, and finished it in exactly eight weeks, on January 2l8t, 1858, reading for the work included; in two months more it waa printed by Hurat and Blackett. I in tended it for one fail volume, but the publishers preferred to issue it in two scant ones ; it has since been reproduced as one railway book by Ward and Lock. Mr. Drummond let me have the run of his famoua historical library at Albury for purposes of reference, etc., beyond what I had in my own ; and I consulted and partially read, for accurate pictures of John's time in England, the histories of Tyrrell, Holinshed, Hume, Poole, Markland ; Thomson's " Magna Charta," James's " Philip Augustus," Milman's "Latin Christi anity," Hallam's "Middle Agea," Maimbourg'a "LivesofthePopes," Banke't "Life of Innocent the Third," Maitland on "The Dark VllI PKEhACE. -

Fall 2013 Fall 2013

W ORCESTER W OMEN’S H ISTORY P ROJECT We remember our past . to better shape our future. WWHP VOL.WWHP 13, VOLUME NO. 2 13, NO. 2 FALL 2013 FALL 2013 WWHP and the Intergenerational Urban Institute at NOTICE Worcester State University are pleased to OF present 18th ANNUAL MEETING Michèle LaRue Thursday, October 24, 2013 in 5:30 p.m. Someone Must Wash the Dishes: Worcester Historical Museum followed by a talk by An Anti-Suffrage Satire Karen Board Moran Many women fought against getting the vote in the early 1900s, on her new book but none with more charm, prettier clothes—and less logic— than the fictional speaker in this satiric monologue written by Gates Along My Path pro-suffragist Marie Jenney Howe, back in 1912. “Woman suf- Booksigning frage is the reform against nature,” declares Howe’s unlikely, but irresistibly likeable, heroine. Light Refreshments “Ladies, get what you want. Pound pillows. Make a scene. Photo by Ken Smith of Quiet Heart Images Make home a hell on earth—but do it in a womanly way! That is All Welcome so much more dignified and refined than walking up to a ballot box and dropping in a piece of paper!” See page 3 for details. Reviewers have called this production “wicked” in its wit, and have labeled Michèle LaRue’s performance "side-splitting." An Illinois native, now based in New York, LaRue is a professional actress who tours nationally with a repertoire of shows by turn-of-the- previous-century American writers. Panel Discussion follows on the unfinished business of women’s rights. -

VIA AIR MAIL Five Dollar Bargains Royce A

I VIA AIR MAIL Five Dollar Bargains Royce A . W ight 21l covers, all with different AIR MAIL announces his return to the United FIELD cancellations (first flights CAM, States and the resumption of his air events, etc.) . • • • . • . • . • • $S.OO mail activities. 40 diff. first flight CAM covers $5.00 I have just prepared a price list (prices. Incidentally are, in gener a l, 40 different first night flight and the lowest I've ever quoted) contain change of schedule covers . $5.00 ing a few hundred of the 1,00 1 bargains 60 air covers, all with commemor I have to offer . A post-card request ative stamps (Hawaii, Ericsson. will bring you this Edison, etc.) . $5.00 PRICE UST 23 80 air mail covers • . • . • . $5.00 With one of the finest stocks in t ha Or, the above 240 covers . .. .•. $20.00 country of C.A.M.'a, F .A.M.'s, Zepp elines, Canada, Mexico. etc. I feel emi... Want to exchanl'e: nently Qualified to serve :v.ou. For In I collect (C.)A.M.'s only. Need rari stance, do you need any of the following ties on all flights, CAM items where CAM- 3S7, 6E2, 7W2, 10N6, 12N4c, regular POD cachet was inadvertent!Y l 5N2. 18E4f, SON4 (price nine cent s) not used on covers. unlisted varieties, FAM-Seattle - Victoria, Tela-Cristobal. etc. What have you, and what do you St. Kitts-St. Johns, etc.. etc. need? Welcome correspondence on cata ZEPPELIN - Tokio - Lakehurst ( World logue listings, new varieties. Flight), Lakehurst - Lakehurst ( Pan. On new routes. -

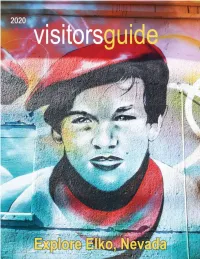

2020 Elko Guide

STAY & PLAY MORE THAN 17,000 SQUARE FEET OF PURE GAMING SATISFACTION AWAITS YOU AT RED LION HOTEL & CASINO. FIND A WIDE VARIETY OF ALL THE HOTTEST SLOTS AND AN EXCITING SELECTION OF TABLE GAMES INCLUDING BLACKJACK, 3CARD POKER, CRAPS, ROULETTE, AND MORE. YOU’LL ENJOY THE FINEST SPORTS BOOK AND THE ONLY LIVE POKER ROOM IN ELKO. GC: 2050 Idaho Street | Elko, NV 89801 | 775-738-8421 | 800-621-1332 RL: 2065 Idaho Street | Elko, NV 89801 | 775-738-2111 | 800-545-0444 HD: 3015 Idaho Street | Elko, NV 89801 | 775-738-8425 | 888-394-8303 wELKOme to Elko, Nevada! hether you call Elko home, are passing through or plan to come and stay a while, we are confident you’ll find something Elko Convention & Wnew and exciting as you #ExploreElko! Visitors Authority 2020 Elko is a vibrant community offering great Board of Directors food; a wide selection of meeting, conference and lodging accommodation options; wonderful events Matt McCarty, Chair throughout the year; art, museums and historical Delmo Andreozzi attractions and an abundance of outdoor recreation Dave Zornes Toni Jewell opportunities. Chip Stone Whether you’re a trail-blazing, peak bagging, galloping adrenaline junkie or an art strolling, line casting, Sunday driving seeker, your adventure starts Follow us on here, the 2020 Visitors Guide, showcasing all the Elko social media! area has to offer. #ExploreElko, @ExploreElko On behalf of the Elko Convention & Visitors Authority and the City of Elko, thank you for being here and we wish you a safe, wonderful visit! Katie Neddenriep Reece Keener Executive Director, Mayor, Elko Convention & City of Elko Visitors Authority 2020 Elko Visitor’s Guide 1 lko is in the northeastern corner of the State of Nevada, situated on the Humboldt River between Reno, Nevada and Salt Lake City, Utah. -

Elwood Fox Appeals from a Judgment of the District Court (Portland

MAINE SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT Reporter of Decisions Decision: 2019 ME 163 Docket: Cum-19-190 Submitted On Briefs: November 21, 2019 Decided: December 10, 2019 PaneL: SAUFLEY, C.J., and ALEXANDER, MEAD, JABAR, HJELM, and HUMPHREY, JJ. ELWOOD L. FOX v. KAREN A. FOX PER CURIAM [¶1] ElWood FoX appeaLs from a judgment of the District Court (PortLand, Cashman, J.) granting Karen FoX’s motion to enforce the provision of the parties’ divorce judgment requiring ElWood to pay toWards his chiLdren’s coLLege expenses. In a separate motion, Karen has requested attorney fees for a frivoLous or contumacious appeaL. See M.R. App. P. 13(f). We affirm the judgment, and We grant Karen’s motion for attorney fees. A. Motion to Enforce [¶2] The parties were divorced in June 2010 by an agreed divorce judgment (Oram, M.), which incorporated a separate settLement agreement. The settLement agreement contains a provision under the heading “CoLLege Expenses” that states: 2 Beginning May 1, 2010, ELWood shaLL contribute the sum of $750 per month into a coLLege fund(s) for the chiLdren’s benefit. He shaLL provide proof of such contributions to Karen by June 1st of each year. ElWood and Karen agree to communicate and cooperate in assisting the chiLdren in the selection and financing, to the best of their respective abiLities, of their post-secondary education institutions and programs. [¶3] The amount of the monthLy obLigation refLects the fact that ElWood is a physician who is more abLe than Karen to contribute to their chiLdren’s coLLege eXpenses. The ChiLd Support Worksheet fiLed With the originaL divorce agreement indicated that ELWood’s annual income Was then $220,000. -

The Transcontinental Pony Express 1860-1861 WEDNESDAY 29 MAY 2019 at 15:00 WATERFRONT CONGRESS CENTRE LEVEL 5 AUDITORIUM

STOCKHOLMIA 2019 PRESENTATION The Transcontinental Pony Express 1860-1861 WEDNESDAY 29 MAY 2019 AT 15:00 WATERFRONT CONGRESS CENTRE LEVEL 5 AUDITORIUM PRESENTED BY Scott R. Tr epel © 2019. All rights reserved by Scott R. Trepel (author) and Robert A. Siegel Auction Galleries, Inc. (publisher). May not be reproduced in any form without the express written consent of the publisher. INTRODUCTION The Transcontinental Pony Express 1860-1861 “News was received every ten days by pony. That coming by the Butterfield route was double the time; what came by steamship was from three to four weeks old when it arrived... It was the pony to which every one looked for intelligence; men prayed for the safety of the little beast, and trembled lest the service should be discontinued.” —Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of California ROM THE VANTAGE POINT OF THE MODERN WORLD, the concept of using horseflesh to provide the Ffastest means of communication is almost too remote to comprehend. And yet so many of us are familiar with the image evoked by the Pony Express—a lone rider galloping across long stretches of grassy plains and desert, climbing the winding trails of the Rocky Mountains, and fighting off the perils of the western frontier to deliver precious letters and news from one coast to the other. When the transcontinental Pony Express started in 1860, communication between the coasts required the physical transport of mail, either by ocean or land. Letters sent by steamship and rail across the Isthmus of Panama took at least three weeks to reach their destination. The alternative land routes were no faster and far less reliable. -

NPS Form 10 900-B

NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. 8/2002) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5-31-2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised) Section number Appendices Page 159 ADDITIONAL DOCUMENTATION Figure 1. William Buckles, “Map showing official SFT Routes…,” Journal of the West (April 1989): 80. Note: The locations of Bent’s Old Fort and New Fort Lyon are reversed; New Fort Lyon was west of Bent’s Old Fort. NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. 8/2002) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5-31-2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised) Section number Appendices Page 160 Figure 2. Susan Calafate Boyle, “Comerciantes, Arrieros, Y Peones: The Hispanos and the Santa Fe Trade,” Southwest Cultural Resources Center: Professional Papers No. 54: Division of History Southwest Region, National Park Service, 1994 [electronic copy on-line]; available from National Park Service, <http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/safe/shs3.htm> (accessed 11 August 2011). NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. 8/2002) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5-31-2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail (Revised) Section number Appendices Page 161 Figure 3. “The Southwest 1820-1835,” National Geographic Magazine, Supplement of the National Geographic November 1982, 630A. NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. 8/2002) OMB No. -

Historical Review

HISTORICAL REVIEW THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI The State Historical Society of Missouri, heretofore organized under the laws of this State, shall be the trustee of this State—Laws of Missouri, 1899, R. S. of Mo., 1949, Chapter 183. OFFICERS 1959-1962 E. L. DALE, Carthage, President L. E. MEADOR, Springfield, First Vice President WILLIAM L. BRADSHAW, Columbia, Second Vice President GEORGE W. SOMERVILLE, Chillicothe, Third Vice President RUSSELL V. DYE, Liberty, Fourth Vice President WILLIAM C. TUCKER, Warrensburg, Fifth Vice President JOHN A. WINKLER, Hannibal, Sixth Vice-President R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Columbia, Secretary and Librarian TRUSTEES Permanent Trustees, Former Presidents of the Society RUSH H. LIMBAUGH, Cape Girardeau E. E. SWAIN, Kirksville ALLEN MCREYNOLDS, Carthage L. M. WHITE, Mexico GEORGE A. ROZIER, Jefferson City G. L. ZWICK, St. Joseph Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1960 RALPH P. BIEBER, St. Louis LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville BARTLETT BODER, St. Joseph W. WALLACE SMITH, Independence L. E. MEADOR, Springfield JACK STAPLETON, Stanberry JOSEPH H. MOORE, Charleston HENRY C. THOMPSON, Bonne Terre Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1961 RAY V. DENSLOW, Trenton FRANK LUTHER MOTT, Columbia ALFRED O. FUERBRINGER, St. Louis GEORGE H. SCRUTON, Sedalia GEORGE FULLER GREEN, Kansas City JAMES TODD, Moberly ROBERT S. GREEN, Mexico T. BALLARD WATTERS, Marshfield Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1962 F. C. BARNHILL, Marshall RALPH P. JOHNSON, Osceola FRANK P. BRIGGS, Macon ROBERT N. JONES, St. Louis HENRY A. BUNDSCHU, Independence FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Columbia W. C. HEWITT, Shelbyville ROY D. WILLIAMS, Boonville EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE The thirty Trustees, the President and the Secretary of the Society, the Governor, Secretary of State, State Treasurer, and President of the University of Missouri constitute the Executive Committee.