Absolute Position Total Internal Reflection Microscopy With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

502-13 Magnifiers and Telescopes

13-1 I and Instrumentation Design Optical OPTI-502 © Copyright 2019 John E. Greivenkamp E. John 2019 © Copyright Section 13 Magnifiers and Telescopes 13-2 I and Instrumentation Design Optical OPTI-502 Visual Magnification Greivenkamp E. John 2019 © Copyright All optical systems that are used with the eye are characterized by a visual magnification or a visual magnifying power. While the details of the definitions of this quantity differ from instrument to instrument and for different applications, the underlying principle remains the same: How much bigger does an object appear to be when viewed through the instrument? The size change is measured as the change in angular subtense of the image produced by the instrument compared to the angular subtense of the object. The angular subtense of the object is measured when the object is placed at the optimum viewing condition. 13-3 I and Instrumentation Design Optical OPTI-502 Magnifiers Greivenkamp E. John 2019 © Copyright As an object is brought closer to the eye, the size of the image on the retina increases and the object appears larger. The largest image magnification possible with the unaided eye occurs when the object is placed at the near point of the eye, by convention 250 mm or 10 in from the eye. A magnifier is a single lens that provides an enlarged erect virtual image of a nearby object for visual observation. The object must be placed inside the front focal point of the magnifier. f h uM h F z z s The magnifying power MP is defined as (stop at the eye): Angular size of the image (with lens) MP Angular size of the object at the near point uM MP d NP 250 mm uU 13-4 I and Instrumentation Design Optical OPTI-502 Magnifiers – Magnifying Power Greivenkamp E. -

Depth of Focus (DOF)

Erect Image Depth of Focus (DOF) unit: mm Also known as ‘depth of field’, this is the distance (measured in the An image in which the orientations of left, right, top, bottom and direction of the optical axis) between the two planes which define the moving directions are the same as those of a workpiece on the limits of acceptable image sharpness when the microscope is focused workstage. PG on an object. As the numerical aperture (NA) increases, the depth of 46 focus becomes shallower, as shown by the expression below: λ DOF = λ = 0.55µm is often used as the reference wavelength 2·(NA)2 Field number (FN), real field of view, and monitor display magnification unit: mm Example: For an M Plan Apo 100X lens (NA = 0.7) The depth of focus of this objective is The observation range of the sample surface is determined by the diameter of the eyepiece’s field stop. The value of this diameter in 0.55µm = 0.6µm 2 x 0.72 millimeters is called the field number (FN). In contrast, the real field of view is the range on the workpiece surface when actually magnified and observed with the objective lens. Bright-field Illumination and Dark-field Illumination The real field of view can be calculated with the following formula: In brightfield illumination a full cone of light is focused by the objective on the specimen surface. This is the normal mode of viewing with an (1) The range of the workpiece that can be observed with the optical microscope. With darkfield illumination, the inner area of the microscope (diameter) light cone is blocked so that the surface is only illuminated by light FN of eyepiece Real field of view = from an oblique angle. -

Section 22-3: Energy, Momentum and Radiation Pressure

Answer to Essential Question 22.2: (a) To find the wavelength, we can combine the equation with the fact that the speed of light in air is 3.00 " 108 m/s. Thus, a frequency of 1 " 1018 Hz corresponds to a wavelength of 3 " 10-10 m, while a frequency of 90.9 MHz corresponds to a wavelength of 3.30 m. (b) Using Equation 22.2, with c = 3.00 " 108 m/s, gives an amplitude of . 22-3 Energy, Momentum and Radiation Pressure All waves carry energy, and electromagnetic waves are no exception. We often characterize the energy carried by a wave in terms of its intensity, which is the power per unit area. At a particular point in space that the wave is moving past, the intensity varies as the electric and magnetic fields at the point oscillate. It is generally most useful to focus on the average intensity, which is given by: . (Eq. 22.3: The average intensity in an EM wave) Note that Equations 22.2 and 22.3 can be combined, so the average intensity can be calculated using only the amplitude of the electric field or only the amplitude of the magnetic field. Momentum and radiation pressure As we will discuss later in the book, there is no mass associated with light, or with any EM wave. Despite this, an electromagnetic wave carries momentum. The momentum of an EM wave is the energy carried by the wave divided by the speed of light. If an EM wave is absorbed by an object, or it reflects from an object, the wave will transfer momentum to the object. -

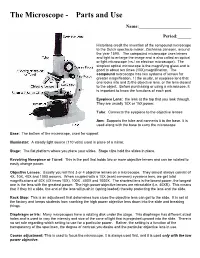

The Microscope Parts And

The Microscope Parts and Use Name:_______________________ Period:______ Historians credit the invention of the compound microscope to the Dutch spectacle maker, Zacharias Janssen, around the year 1590. The compound microscope uses lenses and light to enlarge the image and is also called an optical or light microscope (vs./ an electron microscope). The simplest optical microscope is the magnifying glass and is good to about ten times (10X) magnification. The compound microscope has two systems of lenses for greater magnification, 1) the ocular, or eyepiece lens that one looks into and 2) the objective lens, or the lens closest to the object. Before purchasing or using a microscope, it is important to know the functions of each part. Eyepiece Lens: the lens at the top that you look through. They are usually 10X or 15X power. Tube: Connects the eyepiece to the objective lenses Arm: Supports the tube and connects it to the base. It is used along with the base to carry the microscope Base: The bottom of the microscope, used for support Illuminator: A steady light source (110 volts) used in place of a mirror. Stage: The flat platform where you place your slides. Stage clips hold the slides in place. Revolving Nosepiece or Turret: This is the part that holds two or more objective lenses and can be rotated to easily change power. Objective Lenses: Usually you will find 3 or 4 objective lenses on a microscope. They almost always consist of 4X, 10X, 40X and 100X powers. When coupled with a 10X (most common) eyepiece lens, we get total magnifications of 40X (4X times 10X), 100X , 400X and 1000X. -

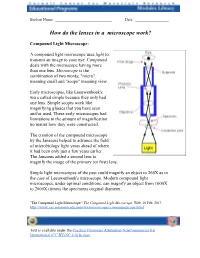

How Do the Lenses in a Microscope Work?

Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ How do the lenses in a microscope work? Compound Light Microscope: A compound light microscope uses light to transmit an image to your eye. Compound deals with the microscope having more than one lens. Microscope is the combination of two words; "micro" meaning small and "scope" meaning view. Early microscopes, like Leeuwenhoek's, were called simple because they only had one lens. Simple scopes work like magnifying glasses that you have seen and/or used. These early microscopes had limitations to the amount of magnification no matter how they were constructed. The creation of the compound microscope by the Janssens helped to advance the field of microbiology light years ahead of where it had been only just a few years earlier. The Janssens added a second lens to magnify the image of the primary (or first) lens. Simple light microscopes of the past could magnify an object to 266X as in the case of Leeuwenhoek's microscope. Modern compound light microscopes, under optimal conditions, can magnify an object from 1000X to 2000X (times) the specimens original diameter. "The Compound Light Microscope." The Compound Light Microscope. Web. 16 Feb. 2017. http://www.cas.miamioh.edu/mbi-ws/microscopes/compoundscope.html Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. - 1 – Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ Now we will describe how a microscope works in somewhat more detail. The first lens of a microscope is the one closest to the object being examined and, for this reason, is called the objective. -

Properties of Electromagnetic Waves Any Electromagnetic Wave Must Satisfy Four Basic Conditions: 1

Chapter 34 Electromagnetic Waves The Goal of the Entire Course Maxwell’s Equations: Maxwell’s Equations James Clerk Maxwell •1831 – 1879 •Scottish theoretical physicist •Developed the electromagnetic theory of light •His successful interpretation of the electromagnetic field resulted in the field equations that bear his name. •Also developed and explained – Kinetic theory of gases – Nature of Saturn’s rings – Color vision Start at 12:50 https://www.learner.org/vod/vod_window.html?pid=604 Correcting Ampere’s Law Two surfaces S1 and S2 near the plate of a capacitor are bounded by the same path P. Ampere’s Law states that But it is zero on S2 since there is no conduction current through it. This is a contradiction. Maxwell fixed it by introducing the displacement current: Fig. 34-1, p. 984 Maxwell hypothesized that a changing electric field creates an induced magnetic field. Induced Fields . An increasing solenoid current causes an increasing magnetic field, which induces a circular electric field. An increasing capacitor charge causes an increasing electric field, which induces a circular magnetic field. Slide 34-50 Displacement Current d d(EA)d(q / ε) 1 dq E 0 dt dt dt ε0 dt dq d ε E dt0 dt The displacement current is equal to the conduction current!!! Bsd μ I μ ε I o o o d Maxwell’s Equations The First Unified Field Theory In his unified theory of electromagnetism, Maxwell showed that electromagnetic waves are a natural consequence of the fundamental laws expressed in these four equations: q EABAdd 0 εo dd Edd s BE B s μ I μ ε dto o o dt QuickCheck 34.4 The electric field is increasing. -

Objective (Optics) 1 Objective (Optics)

Objective (optics) 1 Objective (optics) In an optical instrument, the objective is the optical element that gathers light from the object being observed and focuses the light rays to produce a real image. Objectives can be single lenses or mirrors, or combinations of several optical elements. They are used in microscopes, telescopes, cameras, slide projectors, CD players and many other optical instruments. Objectives are also called object lenses, object glasses, or objective glasses. Microscope objectives are typically designed to be parfocal, which means that when one changes from one lens to another on a Several objective lenses on a microscope. microscope, the sample stays in focus. Microscope objectives are characterized by two parameters, namely, magnification and numerical aperture. The former typically ranges from 5× to 100× while the latter ranges from 0.14 to 0.7, corresponding to focal lengths of about 40 to 2 mm, respectively. For high magnification applications, an oil-immersion objective or water-immersion objective has to be used. The objective is specially designed and refractive index matching oil or water must fill the air gap between the front element and the object to allow the numerical aperture to exceed 1, and hence give greater resolution at high magnification. Numerical apertures as high as 1.6 can be achieved with oil immersion.[1] To find the total magnification of a microscope, one multiplies the A photographic objective, focal length 50 mm, magnification of the objective lenses by that of the eyepiece. aperture 1:1.4 See also • List of telescope parts and construction Diastar projection objective from a 35 mm movie projector, (focal length 400 mm) References [1] Kenneth, Spring; Keller, H. -

6. Imaging: Lenses & Curved Mirrors

6. Imaging: Lenses & Curved Mirrors The basic laws of lenses allow considerable versatility in optical instrument design. The focal length of a lens, f, is the distance at which collimated (parallel) rays converge to a single point after passing through the lens. This is illustrated in Fig. 6.1. A collimated laser beam can thus be brought to a focus at a known position simply by selecting a lens of the desired focal length. Likewise, placing a lens at a distance f can collimate light emanating from a single spot. This simple law is widely used in experimental spectroscopy. For example, this configuration allows collection of the greatest amount of light from a spot, an important consideration in maximizing sensitivity in fluorescence or Raman measurements. The collection Figure 6.1: Parallel beams focused by a lens efficiency of a lens is the ratio Ω/4π, where Ω is the solid angle of the light collected and 4π is the solid angle over all space. The collection efficiency is related to the F-number of the lens, also abbreviated as F/# or f/n. F/# is defined as the ratio of the distance of the object from the lens to the lens diameter (or limiting aperture diameter). In Fig. 6.1 above, the f- number of lens is f/D - ! 1 = 2 . 4" $#4(F / #)&% The collection efficiency increases with decreased focal length and increased lens diameter. Collection efficiency is typically low in optical spectroscopy, such as fluorescence or Raman. On the other hand, two-dimensional imaging (as opposed to light collection) is limited when the object is at a distance of f from the lens because light from only one point in space is collected in this configuration. -

The Human Ear Hearing, Sound Intensity and Loudness Levels

UIUC Physics 406 Acoustical Physics of Music The Human Ear Hearing, Sound Intensity and Loudness Levels We’ve been discussing the generation of sounds, so now we’ll discuss the perception of sounds. Human Senses: The astounding ~ 4 billion year evolution of living organisms on this planet, from the earliest single-cell life form(s) to the present day, with our current abilities to hear / see / smell / taste / feel / etc. – all are the result of the evolutionary forces of nature associated with “survival of the fittest” – i.e. it is evolutionarily{very} beneficial for us to be able to hear/perceive the natural sounds that do exist in the environment – it helps us to locate/find food/keep from becoming food, etc., just as vision/sight enables us to perceive objects in our 3-D environment, the ability to move /locomote through the environment enhances our ability to find food/keep from becoming food; Our sense of balance, via a stereo-pair (!) of semi-circular canals (= inertial guidance system!) helps us respond to 3-D inertial forces (e.g. gravity) and maintain our balance/avoid injury, etc. Our sense of taste & smell warn us of things that are bad to eat and/or breathe… Human Perception of Sound: * The human ear responds to disturbances/temporal variations in pressure. Amazingly sensitive! It has more than 6 orders of magnitude in dynamic range of pressure sensitivity (12 orders of magnitude in sound intensity, I p2) and 3 orders of magnitude in frequency (20 Hz – 20 KHz)! * Existence of 2 ears (stereo!) greatly enhances 3-D localization of sounds, and also the determination of pitch (i.e. -

What's the Size of What You See? Determine the Field Diameter of a Compound Microscope

4th NGSS STEM Conference MAKING SCIENCE COUNT Integrating Math into an NGSS Classroom January 20, 2017 | Pier 15, San Francisco, CA What's the Size of What You See? Determine the field diameter of a compound microscope. By measuring the field diameter of a microscope, you can calculate the real sizes of objects too small to see with the naked eye. Tools and Materials • Compound microscope • Pencil and notepaper to record results • Calculator • Clear plastic metric ruler with millimeter markings (copy this template onto a transparency to make your own) • Optional: microscopic objects to view and measure 4th NGSS STEM Conference MAKING SCIENCE COUNT Integrating Math into an NGSS Classroom January 20, 2017 | Pier 15, San Francisco, CA Assembly None needed. To Do and Notice Find the total magnification of your microscope. First, read the power inscribed on the eyepiece. You’ll find it marked as a number followed by an X, which stands for “times.” Record the eyepiece power. Find the three barrel-shaped objective lenses near the microscope stage. Each will have a different power, which should be marked on the side of the lens. Record the power for each objective. Find the total magnification for each objective lens by multiplying the power of the eyepiece by the power of the objective. Lowest Magnification: Eyepiece x Lowest power objective = ________X Medium Magnification: Eyepiece x Medium power objective = ________X Highest Magnification: Eyepiece x Highest power objective = ________X Set the microscope to its lowest magnification. Slide the plastic metric ruler onto the stage and focus the microscope on the millimeter divisions. -

Reflection and Refraction of Light

Reflection and refraction When light hits a surface, one or more of three things may happen. The light may be reflected back from the surface, transmitted through the material (in which case it will deviate from its initial direction, a process known as refraction) or absorbed by the material if it is not transparent at the wavelength of the incident light. 1. Reflection and refraction Reflection and refraction are governed by two very simple laws. We consider a light wave travelling through medium 1 and striking medium 2. We define the angle of incidence θ as the angle between the incident ray and the normal to the surface (a vector pointing out perpendicular to the surface). For reflection, the reflected ray lies in the plane of incidence, and θ1’ = θ1 For refraction, the refracted ray lies in the plane of incidence, and n1sinθ1 = n2sinθ2 (this expression is called Snell’s law). In the above equations, ni is a dimensionless constant known as the θ1 θ1’ index of refraction or refractive index of medium i. In addition to reflection determining the angle of refraction, n also determines the speed of the light wave in the medium, v = c/n. Just as θ1 is the angle between refraction θ2 the incident ray and the surface normal outside the medium, θ2 is the angle between the transmitted ray and the surface normal inside the medium (i.e. pointing out from the other side of the surface to the original surface normal) 2. Total internal reflection A consequence of Snell’s law is a phenomenon known as total internal reflection. -

Chapter 12: Physics of Ultrasound

Chapter 12: Physics of Ultrasound Slide set of 54 slides based on the Chapter authored by J.C. Lacefield of the IAEA publication (ISBN 978-92-0-131010-1): Diagnostic Radiology Physics: A Handbook for Teachers and Students Objective: To familiarize students with Physics or Ultrasound, commonly used in diagnostic imaging modality. Slide set prepared by E.Okuno (S. Paulo, Brazil, Institute of Physics of S. Paulo University) IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency Chapter 12. TABLE OF CONTENTS 12.1. Introduction 12.2. Ultrasonic Plane Waves 12.3. Ultrasonic Properties of Biological Tissue 12.4. Ultrasonic Transduction 12.5. Doppler Physics 12.6. Biological Effects of Ultrasound IAEA Diagnostic Radiology Physics: a Handbook for Teachers and Students – chapter 12,2 12.1. INTRODUCTION • Ultrasound is the most commonly used diagnostic imaging modality, accounting for approximately 25% of all imaging examinations performed worldwide nowadays • Ultrasound is an acoustic wave with frequencies greater than the maximum frequency audible to humans, which is 20 kHz IAEA Diagnostic Radiology Physics: a Handbook for Teachers and Students – chapter 12,3 12.1. INTRODUCTION • Diagnostic imaging is generally performed using ultrasound in the frequency range from 2 to 15 MHz • The choice of frequency is dictated by a trade-off between spatial resolution and penetration depth, since higher frequency waves can be focused more tightly but are attenuated more rapidly by tissue The information in an ultrasonic image is influenced by the physical processes underlying propagation, reflection and attenuation of ultrasound waves in tissue IAEA Diagnostic Radiology Physics: a Handbook for Teachers and Students – chapter 12,4 12.1.