ED230696.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albuquerque Citizen, 06-26-1908 Hughes & Mccreight

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Citizen, 1891-1906 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-26-1908 Albuquerque Citizen, 06-26-1908 Hughes & McCreight Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_citizen_news Recommended Citation Hughes & McCreight. "Albuquerque Citizen, 06-26-1908." (1908). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_citizen_news/2799 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Citizen, 1891-1906 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRAIN ARRIVALS WEATHER FORECAST . No. i 5 P- - No 4 5. 50 p. m ..; - No. 7 Jo. Si p. m. ? '' PeuTtr, Cfllj.. J111 26. -T- oa! local No. 8 6.40 p. m. shiwerj. Sittirdii inerilli fair. f - No. p m. Albuouemje Citizen 9114$ WE GET THE NEWS FIRST VOLUME 23. ALBUUUEHQDE. NEW MEXICO. FRIDAY, JUNE 2G. 1908. NUMBER 152 ENTHUSIASTIC RECTI MYSTERY HAS NARROW AN INSAN E NOTABLE MEN ASSEMBLE DEATH OF YOUTH ESCAPE FROM HANGS HIMSELF GREETS DELEbK ANDREWS TO HONOR GRDVER CLEVELAND AT INKWELL FLAMES INJAIL Citizens of Albuquerque Joi Extend- Body of Health Seeker From Fire Starting In tFurniture Native Brooded Over Murder President Roosevelt and Governors of ing Thanks of the Commuiucy for His St. Louis Found In Brush Store Spreads to Restaur of Child Because He Several States Attend Funeral Ser- Northwest of the ant. Meat Market Thought Himself to Ability to Secure Irrigation Congress Statesman-- City. and Hall. Blame for Death. vices at Princeton for Dead Appropriation and Additional Fund Simple Ritual of Presbyterian for New Federal Building Crowds HIS COMPANION BOY Wild CANDLE USED ROPeITt Church Constitutes Extent of Serv- Meet Delegate at the Train. -

Keek Named Official Video App of Find Your Grind and Learn to Ride at Sundance Film Festival

KEEK NAMED OFFICIAL VIDEO APP OF FIND YOUR GRIND AND LEARN TO RIDE AT SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL Mobile Video Social Network Provides Once in a Lifetime Opportunity for Snowboard Enthusiasts to Learn to Ride with Pro Snowboarder Luke “Dingo” Trembath and More at Sundance Film Festival NEW YORK, NY (January 5, 2015)— Keek, Inc. (TSXV: KEK; OTCQX: KEEKF) announced today that it has been named the official social video app of Find Your Grind and Learn to Ride at Sundance Film Festival taking place on January 23‐24th, 2015. Keek will be documenting the entire event, providing behind‐the‐ scenes content in addition to sponsoring the Learn to Ride Sundance Contest where one lucky winner and a guest will win a 4‐day VIP trip to Park City Utah for the Sundance Film Festival. Key influencers and celebrities will be “keeking” their experiences on and off the slopes. The Learn To Ride series is a true “bucket list” VIP event, allowing celebrities and media to pair up with professional snowboard athletes to “learn to ride” with the best! This premiere event at Sundance has been voted “most coveted” by Vanity Fair for four years and counting. Past celebrity attendees have included: Lil’ Jon, Krysten Ritter, Kellan Lutz, Adrian Grenier and Alessandra. This year, for the first time ever, talented young adults and children battling chronic illnesses will hit the slopes in their newly gifted Oakley gear, receiving private lessons from pro snowboard athletes. The Keek Learn to Ride Sundance Contest was designed to attract Winter‐lovers and snowboard enthusiasts, alike. -

Prettylittleliars: How Hashtags Drive the Social TV Phenomenon

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses Summer 6-2013 #PrettyLittleLiars: How Hashtags Drive The Social TV Phenomenon Melanie Brozek Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Brozek, Melanie, "#PrettyLittleLiars: How Hashtags Drive The Social TV Phenomenon" (2013). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 93. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #PrettyLittleLiars: How Hashtags Drive The Social TV Phenomenon By Melanie Brozek Prepared for Dr. Esch English Department Salve Regina University May 10, 2013 Brozek 2 #PrettyLittleLiars: How Hashtags Drive The Social TV Phenomenon ABSTRACT: Twitter is used by many TV shows to promote discussion and encourage viewer loyalty. Most successfully, ABC Family uses Twitter to promote the teen drama Pretty Little Liars through the use of hashtags and celebrity interactions. This study analyzes Pretty Little Liars’ use of hashtags created by the network and by actors from the show. It examines how the Pretty Little Liars’ official accounts engage fans about their opinions on the show and encourage further discussion. Fans use the network- generated hashtags within their tweets to react to particular scenes and to hopefully be noticed by managers of official show accounts. -

Russell Hubright

September 2019 Forest Management Chief Russell Hubright Every work day a relatively small segment of the South Carolina Forestry Commission’s workforce ventures onto private property at the request of the owners. These natural resource professionals, known as Project Foresters in our agency, are in the woods performing field work that will enable them to develop forest management plans that are Success Story: Discovery Trail Signs at HSF Page 9 tailored to the landowners’ objectives. Depending on the complexity of the plan, producing the finished product may take as little as a few hours or as much as a week. So, why does the Forestry Commission (https://sref.info/resources/publications/ Hugo’s 30th Anniversary employ foresters who spend such a incremental-economic-impact-of-a- Pages 12 significant part of their time writing south-carolina-forestry-commission- forest management plans? As with forester) showed that for every $1 all services that our agency provides, spent on the salary and expenses of a the answer is that these plans result in Project Forester each year, more than significant public benefit. Another way $24 of additional economic activity is of putting it is that the investment that generated. South Carolina taxpayers are making And we all know that the economic through funding this work has a positive impact of forestry in South Carolina cost-benefit ratio. In fact, a 2016 study is significant - $21 billion annually, conducted by Scott Phillips and Dr. #1 cash crop, #1 export from the port Employee Spotlight: Allison Doherty Tom Straka of Clemson University of Charleston and #2 manufacturing Page 21 September 2019 1 Faifield/Newberry/Union Project Forester Chase Folk meets with a Newberry county landowner about his forest management objectives. -

Unmasking the Teen Cyberbully: a First Amendment-Compliant Approach to Protecting Child Victims of Anonymous, School-Related Internet Harassment Benjamin A

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals November 2017 Unmasking the Teen Cyberbully: A First Amendment-Compliant Approach to Protecting Child Victims of Anonymous, School-Related Internet Harassment Benjamin A. Holden Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Holden, Benjamin A. (2017) "Unmasking the Teen Cyberbully: A First Amendment-Compliant Approach to Protecting Child Victims of Anonymous, School-Related Internet Harassment," Akron Law Review: Vol. 51 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol51/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Holden: Unmasking the Teen Cyberbully UNMASKING THE TEEN CYBERBULLY: A FIRST AMENDMENT-COMPLIANT APPROACH TO PROTECTING CHILD VICTIMS OF ANONYMOUS, SCHOOL-RELATED INTERNET HARASSMENT By: Benjamin A. Holden* I. Introduction and Overview ............................................ 2 II. Minors and The First Amendment ................................. 9 A. The First Amendment and Minors Generally ....... 10 B. The First Amendment and The Student Speech Cases ..................................................................... 10 C. The First Amendment and The Child Protection Cases ..................................................................... 12 1. -

WO 2015/077865 Al 4 June 2015 (04.06.2015) W P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2015/077865 Al 4 June 2015 (04.06.2015) W P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every G06Q 90/00 (2006.01) H04L 12/16 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, G06Q 30/06 (2012.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, (21) International Application Number: DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, PCT/CA20 14/000847 HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, (22) International Filing Date: KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, 26 November 2014 (26.1 1.2014) MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, (25) Filing Language: English SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, (26) Publication Language: English TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 61/908,946 26 November 2013 (26. 11.2013) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, (72) Inventor; and TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, (71) Applicant : BOROVEC, George [CA/CA]; 74A Chemin TJ, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, de la Riviere, Wakefield, Quebec J0X 3G0 (CA). -

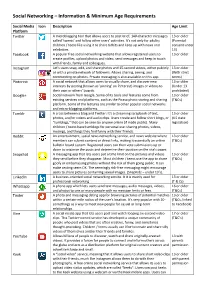

Social Networking – Information & Minimum Age Requirements

Social Networking – Information & Minimum Age Requirements Social Media Icon Description Age Limit Platform Twitter A microblogging tool that allows users to post brief, 140-character messages 13 or older called ‘tweets’ and follow other users' activities. It's not only for adults; (Parental children / teens like using it to share tidbits and keep up with news and consent under celebrities. 13) Facebook A popular free social networking website that allows registered users to 13 or older create profiles, upload photos and video, send messages and keep in touch with friends, family and colleagues. Instagram Let’s users snap, edit, and share photos and 15-second videos, either publicly 13 or older or with a private network of followers. Allows sharing, seeing, and (With strict commenting on photos. Private messaging is also available on this app. terms) Pinterest A social network that allows users to visually share, and discover new 13 or older interests by posting (known as 'pinning' on Pinterest) images or videos to (Under 13 their own or others' boards. prohibited) Google+ Social network from Google. Some of its tools and features come from 13 or older existing services and platforms, such as the Picasa photo storing and sharing (T&Cs) platform. Some of the features are similar to other popular social networks and micro-blogging platforms. Tumblr A cross between a blog and Twitter: It's a streaming scrapbook of text, 13 or older photos, and/or videos and audio clips. Users create and follow short blogs, or (US state "tumblogs," that can be seen by anyone online (if made public). -

Info Student Apps

KNOWING WHAT’S ON A Guide for Understanding Apps. YOUR CHILD’S SMARTPHONE With the widespread use of smartphones among teens and preteens, we can’t be vigilant enough with kids and technology. We want to give them opportunities to learn and grow with integrity in the real and virtual worlds while making sure we are keeping them safe as well. Messaging Apps for Social Apps Photo & Video Apps Hiding Things Apps Social Media and other communications are There are several apps Many applications exist Apps for posting and commonplace among that act as free for the sole purpose of sharing photos and all smartphone users. alternatives to text hiding things from plain videos have always been However, many of these messages sent over view. In many cases popular among teens networks contain adult regular phone and data these apps simply allow and preteens. Many of material not far plans. These apps are users to securely store these apps do not have removed from popular typically seen on iPods personal items. In other content filters, and content. Others are and tablets, but are also cases, the intent is to hide privacy settings are notorious for cyber- common on smartphones. apps, photos, messages, sometimes nonexistent. bullying, and many A few of these messaging or other items the user Several apps also make allow private messaging platforms are popular may want to keep secret. the claim that photos will and photo sharing networks for inappropriate These apps may also be deleted from the contact because users have deceptive names or recipients device after a feel a greater sense of icons. -

Keek MD&A Second Quarter 2015 (With TM Comments

(Formerly Primary Petroleum Corporation) Keek Inc. Keek Inc. (Formerly Primary Petroleum Corporation) Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations for the Three and Nine Months ended November 30, 2015 The following Management’s Discussion and Analysis (“MD&A”) comments on the unaudited consolidated financial condition and results of operations of Keek Inc. for the three and nine months ended November 30, 2015. All data in this MD&A has been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”) as issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (“IASB”) and interpretations of the IFRS Interpretations Committee. The information contained herein should be read in conjunction with Keek’s unaudited condensed consolidated interim financial statements for the three and nine months ended November 30, 2015, (the “financial statements”), and Keek’s annual audited consolidated financial statements for the year ended February 28, 2015. The financial statements have been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”) as issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (“IASB”), using International Accounting Standard (“IAS”) 34, “Interim Financial Reporting”. The Company has consistently applied the same accounting policies and methods of computation as were followed in the preparation of the annual audited consolidated financial statements of Keek for the year ended February 28, 2015. Unless the context otherwise requires, all references to “Keek”, “Corporation”, “Company”, “our”, “us”, and “we” refers to Keek Inc. as consolidated with its subsidiaries. Additional information regarding the Company is available at SEDAR at www.sedar.com. This MD&A is dated January 27, 2016. All amounts are presented in Canadian dollars, unless otherwise noted. -

Latter-Day Screens

Latter- day Screens This page intentionally left blank Latter- day Screens GENDER, SEXUALITY, AND MEDIATED MORMONISM Brenda R. Weber duke university press durham and london 2019 © 2019 DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Minion Pro and Helvetica Neue by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Control Number: 2019943713 isbn 9781478004264 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478004868 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9781478005292 (ebook) Cover art: Big Love (hbo, 2006–11). Publication of this open monograph was the result of Indiana University’s participation in TOME (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem), a col- laboration of the Association of American Universities, the Association of University Presses, and the Association of Research Libraries. TOME aims to expand the reach of long-form humanities and social science scholarship including digital scholarship. Additionally, the program looks to ensure the sustainability of university press monograph publishing by supporting the highest quality scholarship and promoting a new ecology of scholarly publishing in which authors’ institutions bear the publication costs. Funding from Indiana University made it possible to open this publication to the world. This work was partially funded by the Office of the Vice Provost of Research and the IU Libraries. For Michael and Stacey, my North Stars This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS Acknowl edgments ix Past as Prologue. Latter- day Screens and History 1 Introduction. “Well, We Are a Curiosity, Ain’t We?”: Mediated Mormonism 13 1. Mormonism as Meme and Analytic: Spiritual Neoliberalism, Image Management, and Transmediated Salvation 49 2. -

Arabic for Dummies.Pdf

01_772704 ffirs.qxp 3/23/06 9:34 PM Page i Arabic FOR DUMmIES‰ by Amine Bouchentouf 01_772704 ffirs.qxp 3/23/06 9:34 PM Page ii Arabic For Dummies® Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2006 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permit- ted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317-572-3447, fax 317-572-4355, or online at http:// www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley Publishing logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, A Reference for the Rest of Us!, The Dummies Way, Dummies Daily, The Fun and Easy Way, Dummies.com and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Wiley Publishing, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. -

4Chan Ask.Fm Badoo Battlenet

Name Logo Description Category An anonymous message board and content hosting platform. Often CONTENT SHARING 4Chan associated with "Trolling". Ask.fm is a Q&A-based site (and app) that lets users take questions from their followers, and then answer them one at a time, any time they want. In any case, it gives youngsters another reason to talk about themselves other than in the comment section of their own MESSAGING Ask.fm selfies. Although Ask.fm may not be as huge as Instagram or Snapchat, it's a big one to watch, for sure. With such a big interest from youngsters, it absolutely has the potential to become the go-to place for Q&A content. Badoo is a dating-focused social networking service, founded in 2006 and headquarters in Soho, London. Like many other social network sites, you have several options to filter through interests and types to find someone to befriend, date or chat with on Badoo. The advanced DATING Badoo filter allows you to pick a range of ages and distances from where you live. Badoo performs well at finding people for you to connect with locally. On the advanced filter, you can look for more specific traits like body type, kids, education and star sign. A messaging system connecting users of World of Warcraft and other Battlenet content created by Blizzard. Users details are tied to their own MESSAGING individual account which is also used to log into these games. BlackBerry’s BBM is an instant messaging app. You have your own unique 4 digit PIN and other people can only add you as a contact MESSAGING BBM using this.