"Co Regency" Throne Share in Modern Egypt 1805-1952 Enas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9 Abu Naddara: the Forerunner of Egyptian Satirical Press Doaa Adel Mahmoud Kandil Associate Professor Faculty of Tourism &

Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Tourism and Hospitality VOL 13 - NO.1-JUNE 2016 (part1) 9-40 Abu Naddara: The Forerunner of Egyptian Satirical Press Doaa Adel Mahmoud Kandil Associate Professor Faculty of Tourism & Hotels- Helwan University Abstract "Abu Naddara" was an early satirical journal that was first published in Cairo in 1878 by Yaqub Sannu. After Sannu's collision with Khedive Ismail and eventual departure to Paris, he continued to publish it there for almost three successive decades uninterruptedly, however under various changeable names. This journal was by all means the forerunner of satirical opposition press in modern Egypt. In a relatively very short time, "Abu Naddara" gained tremendous success through its humorous but rather bold and scathing criticism of Khedive Ismail's and later Khedive Tewfik's regime that helped turn public opinion against them. No wonder, it soon won popularity because it gave a voice to the downtrodden masses who found in it an outlet for their long-bottled anger. In other words, it turned to be their Vox populi that addressed their pressing problems and expressed their pains. Accordingly, it emerged as a political platform that stood in the face of corruption and social injustice, called for an all-encompassing reform, and most of all raised country-wide national awareness in the hope to develop grass-root activism. This paper investigates the role played by the journal of "Abu Naddara" in spearheading the national opposition against Khedival excesses together with the growing foreign intervention within the closing years of Ismail's reign and the opening years of Tewfik's one that ended up with the British occupation of Egypt. -

1 the Turks and Europe by Gaston Gaillard London: Thomas Murby & Co

THE TURKS AND EUROPE BY GASTON GAILLARD LONDON: THOMAS MURBY & CO. 1 FLEET LANE, E.C. 1921 1 vi CONTENTS PAGES VI. THE TREATY WITH TURKEY: Mustafa Kemal’s Protest—Protests of Ahmed Riza and Galib Kemaly— Protest of the Indian Caliphate Delegation—Survey of the Treaty—The Turkish Press and the Treaty—Jafar Tayar at Adrianople—Operations of the Government Forces against the Nationalists—French Armistice in Cilicia—Mustafa Kemal’s Operations—Greek Operations in Asia Minor— The Ottoman Delegation’s Observations at the Peace Conference—The Allies’ Answer—Greek Operations in Thrace—The Ottoman Government decides to sign the Treaty—Italo-Greek Incident, and Protests of Armenia, Yugo-Slavia, and King Hussein—Signature of the Treaty – 169—271 VII. THE DISMEMBERMENT OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE: 1. The Turco-Armenian Question - 274—304 2. The Pan-Turanian and Pan-Arabian Movements: Origin of Pan-Turanism—The Turks and the Arabs—The Hejaz—The Emir Feisal—The Question of Syria—French Operations in Syria— Restoration of Greater Lebanon—The Arabian World and the Caliphate—The Part played by Islam - 304—356 VIII. THE MOSLEMS OF THE FORMER RUSSIAN EMPIRE AND TURKEY: The Republic of Northern Caucasus—Georgia and Azerbaïjan—The Bolshevists in the Republics of Caucasus and of the Transcaspian Isthmus—Armenians and Moslems - 357—369 IX. TURKEY AND THE SLAVS: Slavs versus Turks—Constantinople and Russia - 370—408 2 THE TURKS AND EUROPE I THE TURKS The peoples who speak the various Turkish dialects and who bear the generic name of Turcomans, or Turco-Tatars, are distributed over huge territories occupying nearly half of Asia and an important part of Eastern Europe. -

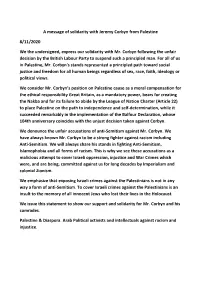

A Message of Solidarity with Jeremy Corbyn from Palestine 8/11/2020

A message of solidarity with Jeremy Corbyn from Palestine 8/11/2020 We the undersigned, express our solidarity with Mr. Corbyn following the unfair decision by the British Labour Party to suspend such a principled man. For all of us in Palestine, Mr. Corbyn's stands represented a principled path toward social justice and freedom for all human beings regardless of sex, race, faith, ideology or political views. We consider Mr. Corbyn’s position on Palestine cause as a moral compensation for the ethical responsibility Great Britain, as a mandatory power, bears for creating the Nakba and for its failure to abide by the League of Nation Charter (Article 22) to place Palestine on the path to independence and self-determination, while it succeeded remarkably in the implementation of the Balfour Declaration, whose 104th anniversary coincides with the unjust decision taken against Corbyn. We denounce the unfair accusations of anti-Semitism against Mr. Corbyn. We have always known Mr. Corbyn to be a strong fighter against racism including Anti-Semitism. We will always share his stands in fighting Anti-Semitism, Islamophobia and all forms of racism. This is why we see these accusations as a malicious attempt to cover Israeli oppression, injustice and War Crimes which were, and are being, committed against us for long decades by Imperialism and colonial Zionism. We emphasize that exposing Israeli crimes against the Palestinians is not in any way a form of anti-Semitism. To cover Israeli crimes against the Palestinians is an insult to the memory of all innocent Jews who lost their lives in the Holocaust. -

The J. Chalhoub Collection of Egypt

© 2018, David Feldman SA All rights reserved All content of this catalogue, such as text, images and their arrangement, is the property of David Feldman SA, and is protected by international copyright laws. The objects displayed in this catalogue are shown with the express permission of their owners. Printed in Germany by Meister Print & Media GmbH Colour disclaimer – We strive to present the lots in this catalogue as accurately as possible. Nevertheless, due to limitations of digital scanners, digital photography, and unintentional variations on the offset printing presses, we cannot guarantee that the colours you see printed are an exact reproduction of the actual item. Although variations are minimal, the images presented herein are intended as a guide only and should not be regarded as absolutely correct. All colours are approximations of actual colours. The Joseph Chalhoub Collection of Egypt I. Commemoratives Monday, December 3, 2018, at 13:00 CET Geneva – David Feldman SA Contact us 59, Route de Chancy, Building D, 3rd floor 1213 Petit Lancy, Geneva, Switzerland Tel. +41 (0)22 727 07 77, Fax +41 (0)22 727 07 78 [email protected] www.davidfeldman.com 50 th The Joseph Chalhoub Collection of Egypt I. Commemoratives Monday, December 3, 2018, at 13:00 CET Geneva – David Feldman SA You are invited to participate VIEWING / VISITE DES LOTS / BESICHTIGUNG Geneva Before December 3 David Feldman SA 59, Route de Chancy, Building D, 3rd floor, 1213 Petit Lancy, Geneva, Switzerland By appointment only – contact Tel.: +41 (0)22 727 07 77 (Viewing of lots on weekends or evenings can be arranged) From December 3 General viewing from 09:00 to 19:00 daily AUCTION / VENTE / AUKTION Monday, December 3 at 13:00 CET All lots (10000-10205) Phone line during the auction / Ligne téléphonique pendant la vente / Telefonleitung während der Auktion Tel. -

Islamic and Indian

ISLAMIC AND INDIAN ART including The Tipu Sultan Collection Tuesday 21 April 2015 Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams 1793 Ltd Directors Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No. 4326560 Robert Brooks Co-Chairman, Colin Sheaf Chairman, Jonathan Baddeley, Andrew McKenzie, Simon Mitchell, Jeff Muse, Registered Office: Montpelier Galleries Malcolm Barber Co-Chairman, Antony Bennett, Matthew Bradbury, Mike Neill, Charlie O’Brien, Giles Peppiatt, Montpelier Street, London SW7 1HH Colin Sheaf Deputy Chairman, Lucinda Bredin, Harvey Cammell, Simon Cottle, Peter Rees, Iain Rushbrook, John Sandon, Matthew Girling Global CEO, Andrew Currie, Paul Davidson, Jean Ghika, Tim Schofield, Veronique Scorer, +44 (0) 20 7393 3900 Patrick Meade Global CEO, Charles Graham-Campbell, Miranda Grant, James Stratton, Roger Tappin, Ralph Taylor, +44 (0) 20 7393 3905 fax Geoffrey Davies, Jonathan Horwich, Richard Harvey, Robin Hereford, Asaph Hyman, Shahin Virani, David Williams, James Knight, Caroline Oliphant, Charles Lanning, Sophie Law, Fergus Lyons, Michael Wynell-Mayow, Suzannah Yip. Hugh Watchorn. Gordon McFarlan, ISLAMIC AND INDIAN ART Tuesday 21 April 2015, at 10.30 101 New Bond Street, London VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES Sunday 12 April +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Claire Penhallurick Monday to Friday 8:30 to 18:00 11.00 - 15.00 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 20 7468 8249 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Monday 13 - Friday 17 April To bid via the internet please [email protected] 9.00 - 16.30 visit bonhams.com As a courtesy to intending Saturday 18 April bidders, Bonhams will provide a 11.00 - 15.00 Please note that bids should be Matthew Thomas written Indication of the physical Sunday 19 April submitted no later than 16:00 +44 20 7468 8270 condition of lots in this sale if a 11.00 - 15.00 on the day prior to the sale. -

Parliament Special Edition

October 2016 22nd Issue Special Edition Our Continent Africa is a periodical on the current 150 Years of Egypt’s Parliament political, economic, and cultural developments in Africa issued by In this issue ................................................... 1 Foreign Information Sector, State Information Service. Editorial by H. E. Ambassador Salah A. Elsadek, Chair- man of State Information Service .................... 2-3 Chairman Salah A. Elsadek Constitutional and Parliamentary Life in Egypt By Mohamed Anwar and Sherine Maher Editor-in-Chief Abd El-Moaty Abouzed History of Egyptian Constitutions .................. 4 Parliamentary Speakers since Inception till Deputy Editor-in-Chief Fatima El-Zahraa Mohamed Ali Current .......................................................... 11 Speaker of the House of Representatives Managing Editor Mohamed Ghreeb (Documentary Profile) ................................... 15 Pan-African Parliament By Mohamed Anwar Deputy Managing Editor Mohamed Anwar and Shaima Atwa Pan-African Parliament (PAP) Supporting As- Translation & Editing Nashwa Abdel Hamid pirations and Ambitions of African Nations 18 Layout Profile of Former Presidents of Pan-African Gamal Mahmoud Ali Parliament ...................................................... 27 Current PAP President Roger Nkodo Dang, a We make every effort to keep our Closer Look .................................................... 31 pages current and informative. Please let us know of any Women in Egyptian and African Parliaments, comments and suggestions you an endless march of accomplishments .......... 32 have for improving our magazine. [email protected] Editorial This special issue of “Our Continent Africa” Magazine coincides with Egypt’s celebrations marking the inception of parliamentary life 150 years ago (1688-2016) including numerous func- tions atop of which come the convening of ses- sions of both the Pan-African Parliament and the Arab Parliament in the infamous city of Sharm el-Sheikh. -

•C ' CONFIDENTIAL EGYPT October 8, 1946 Section 1 ARCHIVE* J 4167/39/16 Copy No

THIS DOCUMENT IS THE PROPERTY OF HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY'S GOYERNMENT •C ' CONFIDENTIAL EGYPT October 8, 1946 Section 1 ARCHIVE* J 4167/39/16 Copy No. LEADING PERSONALITIES IN EGYPT Mr. Bowker to Mr. Bevin. (Received 8th October) (No. 1051. Confidential) 53. Ibrahim Abdul Hadi Pasha. Sir, Cairo, 30th September, 1946 54. Maitre Abdel Hamid Abdel Hakk. With reference to Mr. Farquhar's despatch 55. Nabil Abbas Halim. No. 1205 of-29th August, 1945, I have the honour 56. Maitre Ahmed Hamza. to transmit a revised list of personalities in Egypt. 57. Abdel Malek Hamza Bey. I have, &c. 58. El Lewa Mohammed Saleh Harb Pasha. JAMES BOWKEE. 59. Mahmoud Hassan Pasha. 60. Mohammed Abdel Khalek Hassouna Pasha. 61. Dr. Hussein Heikal Pasha. Enclosure 62. Sadek Henein Pasha. INDEX 63. Mahmoud Tewfik el-Hifnawi Pasha. 64. Neguib el-Hilaly Pasha. I.—Egyptian Personalitits 65. Ahmed Hussein Effendi. 1. Fuad Abaza Pasha. 66. Dr. Tahra Hussein. 2. Ibrahim Dessuki Abaza Pasha. 67. Dr. Ali Ibrahim Pasha, C.B.E. 3. Maitre Mohammed Fikri Abaza. 68. Kamel Ibrahim Bey. 4. Mohammed Ahmed Abboud Pasha. 69. Mohammed Hilmy Issa Pasha. 5. Dr. Hafez Afifi Pasha. 70. Aziz Izzet Pasha, G.C.V.O. 6. Abdel Kawi Ahmed Pasha. 71. Ahmed Kamel Pasha. 7. Ibrahim Sid Ahmed Bey. 72. ,'Lewa Ahmed Kamel Pasha. 8. Murad Sid Ahmed Pasha. 73. Ibrahim Fahmy Kerim Pasha. 9. Ahmed All Pasha, K.C.V.O. 74. Mahmoud Bey Khalil. 10. Prince Mohammed All, G.C.B., G.C.M.G. 75. Ahmed Mohammed Khashaba Pasha. 11. Tarraf Ali Pasha. -

The Interface of Religious and Political Conflict in Egyptian Theatre

The Interface of Religious and Political Conflict in Egyptian Theatre Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amany Youssef Seleem, Stage Directing Diploma Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Lesley Ferris, Advisor Nena Couch Beth Kattelman Copyright by Amany Seleem 2013 Abstract Using religion to achieve political power is a thematic subject used by a number of Egyptian playwrights. This dissertation documents and analyzes eleven plays by five prominent Egyptian playwrights: Tawfiq Al-Hakim (1898- 1987), Ali Ahmed Bakathir (1910- 1969), Samir Sarhan (1938- 2006), Mohamed Abul Ela Al-Salamouni (1941- ), and Mohamed Salmawi (1945- ). Through their plays they call attention to the dangers of blind obedience. The primary methodological approach will be a close literary analysis grounded in historical considerations underscored by a chronology of Egyptian leadership. Thus the interface of religious conflict and politics is linked to the four heads of government under which the playwrights wrote their works: the eras of King Farouk I (1920-1965), President Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918-1970), President Anwar Sadat (1918-1981), and President Hosni Mubarak (1928- ). While this study ends with Mubarak’s regime, it briefly considers the way in which such conflict ended in the recent reunion between religion and politics with the election of Mohamed Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, as president following the Egyptian Revolution of 2011. This research also investigates how these scripts were written— particularly in terms of their adaptation from existing canonical work or historical events and the use of metaphor—and how they were staged. -

Annales Islamologiques

MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE ANNALES ISLAMOLOGIQUES en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne AnIsl 50 (2016), p. 107-143 Mohamed Elshahed Egypt Here and There. The Architectures and Images of National Exhibitions and Pavilions, 1926–1964 Conditions d’utilisation L’utilisation du contenu de ce site est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Toute autre utilisation du site et de son contenu est soumise à une autorisation préalable de l’éditeur (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). Le copyright est conservé par l’éditeur (Ifao). Conditions of Use You may use content in this website only for your personal, noncommercial use. Any further use of this website and its content is forbidden, unless you have obtained prior permission from the publisher (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). The copyright is retained by the publisher (Ifao). Dernières publications 9782724708288 BIFAO 121 9782724708424 Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l'étranger (BAEFE) 9782724707878 Questionner le sphinx Philippe Collombert (éd.), Laurent Coulon (éd.), Ivan Guermeur (éd.), Christophe Thiers (éd.) 9782724708295 Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 30 Sylvie Marchand (éd.) 9782724708356 Dendara. La Porte d'Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724707953 Dendara. La Porte d’Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724708394 Dendara. La Porte d'Hathor Sylvie Cauville 9782724708011 MIDEO 36 Emmanuel Pisani (éd.), Dennis Halft (éd.) © Institut français d’archéologie orientale - Le Caire Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 1 / 1 MohaMed elshahed* Egypt Here and There The Architectures and Images of National Exhibitions and Pavilions, 1926–1964 • abstract In 1898 the first agricultural exhibition was held on the island of Gezira in a location accessed from Cairo’s burgeoning modern city center via the Qasr el-Nil Bridge. -

Engagement: Coptic Christian Revival and the Performative Politics of Song

THE POLITICS OF (DIS)ENGAGEMENT: COPTIC CHRISTIAN REVIVAL AND THE PERFORMATIVE POLITICS OF SONG by CAROLYN M. RAMZY A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Carolyn Ramzy (2014) Abstract The Performative Politics of (Dis)Engagment: Coptic Christian Revival and the Performative Politics of Song Carolyn M. Ramzy A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Music, University of Toronto 2014 This dissertation explores Coptic Orthodox political (dis)engagement through song, particularly as it is expressed through the colloquial Arabic genre of taratil. Through ethnographic and archival research, I assess the genre's recurring tropes of martyrdom, sacrifice, willful withdrawal, and death as emerging markers of community legitimacy and agency in Egypt's political landscape before and following the January 25th uprising in 2011. Specifically, I explore how Copts actively perform as well as sing a pious and modern citizenry through negations of death and a heavenly afterlife. How do they navigate the convergences and contradictions of belonging to a nation as minority Christian citizens among a Muslim majority while feeling that they have little real civic agency? Through a number of case studies, I trace the discursive logics of “modernizing” religion into easily tangible practices of belonging to possess a heavenly as well as an earthly nation. I begin with Sunday Schools in the predominately Christian and middle-class neighborhood of Shubra where educators made the poetry of the late Coptic Patriarch, Pope Shenouda III, into taratil and drew on their potentials of death and withdrawal to reform a Christian moral interiority and to teach a modern and pious Coptic citizenry. -

Personal Information Name: Mohamed Naguib Mohamed Date

C.V. Personal Name: Mohamed Naguib Mohamed information Date of birth: 2-6-1985 E-mail:- [email protected] [email protected] - Mobile : (+2)0111-6090451 Marital status: Married Education PhD in Microbiology Botany and Microbiology Department Faculty of Science Cairo University Giza, Egypt 2012-2016 Master degree in Microbiology Botany Department Cairo University Giza, Egypt 2007-2011 Bachelor of Science Cairo University Giza, Egypt 2002-2006 ThanaweyaAmma, Science Major El-Sayedia Giza, Egypt 1998-2001 Master degree Biodegradation of some Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by some title Soil fungi PhD degree title “Purification and characterization of laccase from some soil microorganisms” Professi onal 1- Teaching in Cairo University since 20 07 . Career 2- Biomap &Wallacea International operations Supervision 2008. Experience 3-Treasurer for the The Egyptian Botanical Society 2018. 4- Manager of IT unit in Faculty of Science, Cairo University 2018. 5- Executive manager in FLDC from 2015. 6- International Certified Professional Trainer from 2017. Attended 1- CIPT (Certified International Professional Trainer) course in 2017. Training 2- Executive Manager course from FLDC in 2015. Courses 3-Control lab. Of Oil &Soap Company from 1/7/2002 to 1/8/2002 4-Pharmacy Company from 1/7/2006 to 1/10/2006. 5-Molecular biology Practical Courses (PCR, Cloning ) in Animal reproduction research institute. 6- Molecular biology practi cal Courses for stuff members in Cairo University by HEEPF. 7- Biomap &Wallacea International British operations Training in 2006. 8-Faculty and leadership development center (FLDC) training courses a) Competing for research funds. b) Conference organization. c) The credit hour systems. -

Bingöl Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Yıl: 4/ Cilt: 4 /Sayı:8/ Güz 2014

Bingöl Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Yıl: 4/ Cilt: 4 /Sayı:8/ Güz 2014 HISTORICAL ALLEGORIES IN NAGUIB MAHFOUZ’S CAIRO TRILOGY Naguib M ahfouz’un Kahire Üçlemesi Adli Eserindeki Tarihsel Alegoriler Özlem AYDIN* Abstract The purpose o f this work is to analyze the “Cairo Trilogy” o f a Nobel Prize winner for literature, the Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz with the method o f new historicism. In “Cairo Trilogy”, Mahfouz presents the striking events oflate history of Egypt by weaving them with fıction. As history is one o f the most useful sources of literature the dense relationship between history and literature is beyond argument. When viewed from this aspect, a new historicist approach to literature will provide a widened perspective to both literature and history by enabling different possibilities for crucial reading. It is expected that the new historicist analysis o f “Cairo Trilogy” will enable a better insight into the literature and historical background o f Egypt. Key Words: Naguib Mahfouz, Cairo Trilogy, History, Egypt, New Historicism Özet Bu çalışmanın amacı Mısır ’lı Nobel ödüllü yazar Naguib Mahfouz ’un “Kahire Üçlemesi”adlı eserini yeni tarihselcilik metodunu kullanarak analiz etmektir. “Kahire Üçlemesi”nde Mahfouz, Mısır’ın yakın tarihindeki çarpıcı olayları kurgu ile harmanlayarak sunmuştur. Tarih, edebiyatın en faydalı kaynaklarından biri olduğundan, tarih ve edebiyat arasındaki sıkı ilişki tartışılmazdır. Bu açıdan bakıldığında, edebiyata yeni tarihselci bir yaklaşım çapraz okuma konusunda farklı imkanlar sunarak hem edebiyata hem tarihe daha geniş bir bakış açısı sağlayacaktır. “Kahire Üçlemesi”nin yeni tarihselci analizinin Mısır’ın edebiyatının ve tarihsel arkaplanının daha iyi kavranmasını sağlaması beklenmektedir.