CORE View Metadata, Citation and Similar Papers at Core.Ac.Uk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Struggle for Citizenship

OCTOBER 2017 Women’s Struggle for Citizenship: Civil Society and Constitution Making after the Arab Uprisings JOSÉ S. VERICAT Cover Photo: Marchers on International ABOUT THE AUTHORS Women’s Day, Cairo, Egypt, March 8, 2011. Al Jazeera English. JOSÉ S. VERICAT is an Adviser at the International Peace Institute. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper represent those of the author Email: [email protected] and not necessarily those of the International Peace Institute. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit of ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS a well-informed debate on critical policies and issues in international The author would like to thank Mohamed Elagati and affairs. Nidhal Mekki for their useful feedback. This project would not have seen the light of day without the input of dozens IPI Publications of civil society activists from Egypt, Tunisia, and Yemen, as Adam Lupel, Vice President well as several from Libya and Syria, who believed in its Albert Trithart, Associate Editor value and selflessly invested their time and energy into it. Madeline Brennan, Assistant Production Editor To them IPI is very grateful. Within IPI, Amal al-Ashtal and Waleed al-Hariri provided vital support at different stages Suggested Citation: of the project’s execution. José S. Vericat, “Women’s Struggle for Citizenship: Civil Society and IPI owes a debt of gratitude to its many donors for their Constitution Making after the Arab generous support. In particular, IPI would like to thank the Uprisings,” New York: International governments of Finland and Norway for making this Peace Institute, October 2017. publication possible. -

Petition To: United Nations Working

PETITION TO: UNITED NATIONS WORKING GROUP ON ARBITRARY DETENTION Mr Mads Andenas (Norway) Mr José Guevara (Mexico) Ms Shaheen Ali (Pakistan) Mr Sètondji Adjovi (Benin) Mr Vladimir Tochilovsky (Ukraine) HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY COPY TO: UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF OPINION AND EXPRESSION, MR DAVID KAYE; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE RIGHTS TO FREEDOM OF PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY AND OF ASSOCIATION, MR MAINA KIAI; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS, MR MICHEL FORST. in the matter of Alaa Abd El Fattah (the “Petitioner”) v. Egypt _______________________________________ Petition for Relief Pursuant to Commission on Human Rights Resolutions 1997/50, 2000/36, 2003/31, and Human Rights Council Resolutions 6/4 and 15/1 Submitted by: Media Legal Defence Initiative Electronic Frontier Foundation The Grayston Centre 815 Eddy Street 28 Charles Square San Francisco CA 94109 London N1 6HT BASIS FOR REQUEST The Petitioner is a citizen of the Arab Republic of Egypt (“Egypt”), which acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”) on 14 January 1982. 1 The Constitution of the Arab Republic of Egypt 2014 (the “Constitution”) states that Egypt shall be bound by the international human rights agreements, covenants and conventions it has ratified, which shall have the force of law after publication in accordance with the conditions set out in the Constitution. 2 Egypt is also bound by those principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”) that have acquired the status of customary international law. -

A Short History of Egypt – to About 1970

A Short History of Egypt – to about 1970 Foreword................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 1. Pre-Dynastic Times : Upper and Lower Egypt: The Unification. .. 3 Chapter 2. Chronology of the First Twelve Dynasties. ............................... 5 Chapter 3. The First and Second Dynasties (Archaic Egypt) ....................... 6 Chapter 4. The Third to the Sixth Dynasties (The Old Kingdom): The "Pyramid Age"..................................................................... 8 Chapter 5. The First Intermediate Period (Seventh to Tenth Dynasties)......10 Chapter 6. The Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties (The Middle Kingdom).......11 Chapter 7. The Second Intermediate Period (about I780-1561 B.C.): The Hyksos. .............................................................................12 Chapter 8. The "New Kingdom" or "Empire" : Eighteenth to Twentieth Dynasties (c.1567-1085 B.C.)...............................................13 Chapter 9. The Decline of the Empire. ...................................................15 Chapter 10. Persian Rule (525-332 B.C.): Conquest by Alexander the Great. 17 Chapter 11. The Early Ptolemies: Alexandria. ...........................................18 Chapter 12. The Later Ptolemies: The Advent of Rome. .............................20 Chapter 13. Cleopatra...........................................................................21 Chapter 14. Egypt under the Roman, and then Byzantine, Empire: Christianity: The Coptic Church.............................................23 -

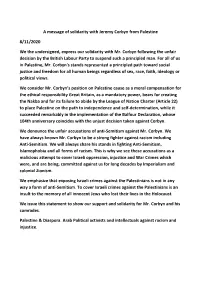

A Message of Solidarity with Jeremy Corbyn from Palestine 8/11/2020

A message of solidarity with Jeremy Corbyn from Palestine 8/11/2020 We the undersigned, express our solidarity with Mr. Corbyn following the unfair decision by the British Labour Party to suspend such a principled man. For all of us in Palestine, Mr. Corbyn's stands represented a principled path toward social justice and freedom for all human beings regardless of sex, race, faith, ideology or political views. We consider Mr. Corbyn’s position on Palestine cause as a moral compensation for the ethical responsibility Great Britain, as a mandatory power, bears for creating the Nakba and for its failure to abide by the League of Nation Charter (Article 22) to place Palestine on the path to independence and self-determination, while it succeeded remarkably in the implementation of the Balfour Declaration, whose 104th anniversary coincides with the unjust decision taken against Corbyn. We denounce the unfair accusations of anti-Semitism against Mr. Corbyn. We have always known Mr. Corbyn to be a strong fighter against racism including Anti-Semitism. We will always share his stands in fighting Anti-Semitism, Islamophobia and all forms of racism. This is why we see these accusations as a malicious attempt to cover Israeli oppression, injustice and War Crimes which were, and are being, committed against us for long decades by Imperialism and colonial Zionism. We emphasize that exposing Israeli crimes against the Palestinians is not in any way a form of anti-Semitism. To cover Israeli crimes against the Palestinians is an insult to the memory of all innocent Jews who lost their lives in the Holocaust. -

Playing with Fire. the Muslim Brotherhood and the Egyptian

Playing with Fire.The Muslim Brotherhood and the Egyptian Leviathan Daniela Pioppi After the fall of Mubarak, the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) decided to act as a stabilising force, to abandon the street and to lend democratic legiti- macy to the political process designed by the army. The outcome of this strategy was that the MB was first ‘burned’ politically and then harshly repressed after having exhausted its stabilising role. The main mistakes the Brothers made were, first, to turn their back on several opportunities to spearhead the revolt by leading popular forces and, second, to keep their strategy for change gradualist and conservative, seeking compromises with parts of the former regime even though the turmoil and expectations in the country required a much bolder strategy. Keywords: Egypt, Muslim Brotherhood, Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, Arab Spring This article aims to analyse and evaluate the post-Mubarak politics of the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) in an attempt to explain its swift political parable from the heights of power to one of the worst waves of repression in the movement’s history. In order to do so, the analysis will start with the period before the ‘25th of January Revolution’. This is because current events cannot be correctly under- stood without moving beyond formal politics to the structural evolution of the Egyptian system of power before and after the 2011 uprising. In the second and third parts of this article, Egypt’s still unfinished ‘post-revolutionary’ political tran- sition is then examined. It is divided into two parts: 1) the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF)-led phase from February 2011 up to the presidential elections in summer 2012; and 2) the MB-led phase that ended with the military takeover in July 2013 and the ensuing violent crackdown on the Brotherhood. -

The Most Prominent Violations of Press and Media Freedom in Egypt During 2017

Annual Report on: Freedom of Press and Media in Egypt 2017 Annual on: Freedom of PRreses apndo Merdtia in Egypt 2017 Conducted by Ahmed Abo Elmagd Reviewed by Ahmed Ragab Cover designed by Ahmed Sobhy Published year 2017 Annual Report on: Freedom of Press and Media in Egypt 2017 The Egyptian Center for Public Policy Studies (ECPPS) is a non-governmental, non- party and non-profit organization .It is mission is to propose public policies that aim at reforming the Egyptian legal and economic systems. ECPPS’s goal is to enhance the principles of free market, individual freedom and the rule of law. The Egyptian Center for Public Policy Studies (ECPPS) 1 Annual Report on: Freedom of Press and Media in Egypt 2017 In 2017, the Egyptian Center for Public Policies Studies issues a monthly monitoring to measure (Legislative climate, political climate, economic climate, media performance and civil society role) in regard to freedom of media and journalism in Egypt, in trying to stand on events, changes, violations which happen and effect on media and journalism statement in Egypt. The Egyptian Center for Public Policies Studies held general interviews and conferences with the participation of many parties and different entities (members of Parliament, members of Press Syndicate, researchers and members of media and journalism councils) just to review, present important events and actors observed over the year. This report includes an “annual detailed report for the statement of media and journalism in Egypt in 2017”. Important events and changes which affected negatively or positively in the climate of freedom of press and media work in Egypt in 2017 in addition to precise recommendations for decision makers based on these events and changes to improve the climate of media and journalism in Egypt. -

Parliament Special Edition

October 2016 22nd Issue Special Edition Our Continent Africa is a periodical on the current 150 Years of Egypt’s Parliament political, economic, and cultural developments in Africa issued by In this issue ................................................... 1 Foreign Information Sector, State Information Service. Editorial by H. E. Ambassador Salah A. Elsadek, Chair- man of State Information Service .................... 2-3 Chairman Salah A. Elsadek Constitutional and Parliamentary Life in Egypt By Mohamed Anwar and Sherine Maher Editor-in-Chief Abd El-Moaty Abouzed History of Egyptian Constitutions .................. 4 Parliamentary Speakers since Inception till Deputy Editor-in-Chief Fatima El-Zahraa Mohamed Ali Current .......................................................... 11 Speaker of the House of Representatives Managing Editor Mohamed Ghreeb (Documentary Profile) ................................... 15 Pan-African Parliament By Mohamed Anwar Deputy Managing Editor Mohamed Anwar and Shaima Atwa Pan-African Parliament (PAP) Supporting As- Translation & Editing Nashwa Abdel Hamid pirations and Ambitions of African Nations 18 Layout Profile of Former Presidents of Pan-African Gamal Mahmoud Ali Parliament ...................................................... 27 Current PAP President Roger Nkodo Dang, a We make every effort to keep our Closer Look .................................................... 31 pages current and informative. Please let us know of any Women in Egyptian and African Parliaments, comments and suggestions you an endless march of accomplishments .......... 32 have for improving our magazine. [email protected] Editorial This special issue of “Our Continent Africa” Magazine coincides with Egypt’s celebrations marking the inception of parliamentary life 150 years ago (1688-2016) including numerous func- tions atop of which come the convening of ses- sions of both the Pan-African Parliament and the Arab Parliament in the infamous city of Sharm el-Sheikh. -

•C ' CONFIDENTIAL EGYPT October 8, 1946 Section 1 ARCHIVE* J 4167/39/16 Copy No

THIS DOCUMENT IS THE PROPERTY OF HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY'S GOYERNMENT •C ' CONFIDENTIAL EGYPT October 8, 1946 Section 1 ARCHIVE* J 4167/39/16 Copy No. LEADING PERSONALITIES IN EGYPT Mr. Bowker to Mr. Bevin. (Received 8th October) (No. 1051. Confidential) 53. Ibrahim Abdul Hadi Pasha. Sir, Cairo, 30th September, 1946 54. Maitre Abdel Hamid Abdel Hakk. With reference to Mr. Farquhar's despatch 55. Nabil Abbas Halim. No. 1205 of-29th August, 1945, I have the honour 56. Maitre Ahmed Hamza. to transmit a revised list of personalities in Egypt. 57. Abdel Malek Hamza Bey. I have, &c. 58. El Lewa Mohammed Saleh Harb Pasha. JAMES BOWKEE. 59. Mahmoud Hassan Pasha. 60. Mohammed Abdel Khalek Hassouna Pasha. 61. Dr. Hussein Heikal Pasha. Enclosure 62. Sadek Henein Pasha. INDEX 63. Mahmoud Tewfik el-Hifnawi Pasha. 64. Neguib el-Hilaly Pasha. I.—Egyptian Personalitits 65. Ahmed Hussein Effendi. 1. Fuad Abaza Pasha. 66. Dr. Tahra Hussein. 2. Ibrahim Dessuki Abaza Pasha. 67. Dr. Ali Ibrahim Pasha, C.B.E. 3. Maitre Mohammed Fikri Abaza. 68. Kamel Ibrahim Bey. 4. Mohammed Ahmed Abboud Pasha. 69. Mohammed Hilmy Issa Pasha. 5. Dr. Hafez Afifi Pasha. 70. Aziz Izzet Pasha, G.C.V.O. 6. Abdel Kawi Ahmed Pasha. 71. Ahmed Kamel Pasha. 7. Ibrahim Sid Ahmed Bey. 72. ,'Lewa Ahmed Kamel Pasha. 8. Murad Sid Ahmed Pasha. 73. Ibrahim Fahmy Kerim Pasha. 9. Ahmed All Pasha, K.C.V.O. 74. Mahmoud Bey Khalil. 10. Prince Mohammed All, G.C.B., G.C.M.G. 75. Ahmed Mohammed Khashaba Pasha. 11. Tarraf Ali Pasha. -

Master Thesis

MEASURES BY THE EGYPTIAN GOVERNMENT TO COUNTER THE EXPLOITATION OF (SOCIAL) MEDIA - FACEBOOK AND AL JAZEERA Master Thesis Name: Rajko Smaak Student number: S1441582 Study: Master Crisis and Security Management Date: January 13, 2016 The Hague, The Netherlands Master Thesis: Measures by the Egyptian government to counter the exploitation of (social) media II Leiden University CAPSTONE PROJECT ‘FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION VERSUS FREEDOM FROM INTIMIDATION MEASURES BY THE EGYPTIAN GOVERNMENT TO COUNTER THE EXPLOITATION OF (SOCIAL) MEDIA - FACEBOOK AND AL JAZEERA BY Rajko Smaak S1441582 MASTER THESIS Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Crisis and Security Management at Leiden University, The Hague Campus. January 13, 2016 Leiden, The Netherlands Adviser: Prof. em. Alex P. Schmid Second reader: Dhr. Prof. dr. Edwin Bakker Master Thesis: Measures by the Egyptian government to counter the exploitation of (social) media III Leiden University Master Thesis: Measures by the Egyptian government to counter the exploitation of (social) media IV Leiden University Abstract During the Arab uprisings in 2011, social media played a key role in ousting various regimes in the Middle East and North Africa region. Particularly, social media channel Facebook and TV broadcast Al Jazeera played a major role in ousting Hosni Mubarak, former president of Egypt. Social media channels eases the ability for people to express, formulate, send and perceive messages on political issues. However, some countries demonstrate to react in various forms of direct and indirect control of these media outlets. Whether initiated through regulations or punitive and repressive measures such as imprisonment and censorship of media channels. -

Egypt As a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics'

H-Women Yilmaz on Baron, 'Egypt As a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics' Review published on Wednesday, October 22, 2008 Beth Baron. Egypt As a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. 292 pp. $60.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-520-23857-2. Reviewed by Hale Yilmaz Published on H-Women (October, 2008) Commissioned by Holly S. Hurlburt Nationalism, Gender, and Politics in Egypt In Egypt as a Woman Beth Baron explores the connections between Egyptian nationalism, gendered images and discourses of the nation, and the politics of elite Egyptian women from the late nineteenth century to World War Two, focusing on the interwar period. Baron builds on earlier works on Egyptian nationalist and women's history (especially Margot Badran's and her own) and draws on a wide array of primary sources such as newspapers, magazines, archival records, memoirs, literary sources such as ballads and plays, and visual sources such as cartoons, photographs, and monuments, as well as on the scholarship on nationalism, feminism, and gender. This book can be read as a monograph focused on the connections between nationalism, gender, and politics, or it can be read as a collection of essays on these themes. (Parts of three of the chapters had appeared earlier in edited volumes.) The book's two parts focus on images of the nation, and the politics of women nationalists. It opens with the story of the official ceremony for the unveiling of Mahmud Mukhtar's monumental sculpture Nahdat Misr (The Awakening of Egypt) depicting Egypt as a woman. Baron draws attention to the paradox of the complete absence of women from a national ceremony celebrating a work in which woman represented the nation. -

The Muslim Brotherhood's

chapter 9 The Muslim Brotherhood’s ‘Virtuous society’ and State Developmentalism in Egypt: The Politics of ‘Goodness’ Marie Vannetzel Abstract The rise of Islamists in Arab countries has often been explained by their capacity to offer an alternative path of development, based on a religious vision and on a paral- lel welfare sector, challenging post-independence developmentalist states. Taking the case of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, and building on ethnographic fieldwork, this chapter aims to contribute to this debate, exploring how conflict and cooperation were deeply intertwined in the relationships between this movement and Mubarak’s regime. Rather than postulating any structural polarisation, or—in contrast—any simplistic authoritarian coalition, the author argues that the vision of two models of development opposing one another unravels when we move from abstract approach- es towards empirical studies. On the ground, both the Muslim Brotherhood and the former regime elites participated in what the author calls the politics of ‘goodness’ (khayr), which she defines as a conflictual consensus built on entrenched welfare net- works, and on an imaginary matrix mixing various discursive repertoires of state de- velopmentalism and religious welfare. The chapter also elaborates an interpretative framework to aid understanding of the sudden rise and fall of the Brotherhood in the post-2011 period, showing that, beyond its failure, what is at stake is the breakdown of the politics of ‘goodness’ altogether. 1 Introduction Islamists’ momentum in Arab countries has often been explained by their ca- pacity to offer an alternative path of development, based on a religious vision and on a ‘shadow and parallel welfare system […] with a profound ideologi- cal impact on society’ (Bibars, 2001, 107), through which they challenged post- independence developmentalist states (Sullivan and Abed-Kotob, 1999). -

The Right to Information in Egypt and Prospects of Renegotiating a New Social Order

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2017 The right to information in Egypt and prospects of renegotiating a new social order Farida Ibrahim Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Ibrahim, F. (2017).The right to information in Egypt and prospects of renegotiating a new social order [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/680 MLA Citation Ibrahim, Farida. The right to information in Egypt and prospects of renegotiating a new social order. 2017. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/680 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy The Right to Information in Egypt and Prospects of Renegotiating a New Social Order A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Law In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the LL.M. Degree in International and Comparative Law By Farida Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim February 2017 The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy The RIGHT TO INFORMATION IN EGYPT AND PROSPECTS OF RENEGOTIATING A NEW SOCIAL ORDER A Thesis Submitted by Farida Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim to the Department of Law February 2017 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the LL.M.