The Politics of Christian Minorities in the Middle East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ashley Walsh

Civil religion in Britain, 1707 – c. 1800 Ashley James Walsh Downing College July 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. All dates have been presented in the New Style. 1 Acknowledgements My greatest debt is to my supervisor, Mark Goldie. He encouraged me to study civil religion; I hope my performance vindicates his decision. I thank Sylvana Tomaselli for acting as my adviser. I am also grateful to John Robertson and Brian Young for serving as my examiners. My partner, Richard Johnson, and my parents, Maria Higgins and Anthony Walsh, deserve my deepest gratitude. My dear friend, George Owers, shared his appreciation of eighteenth- century history over many, many pints. He also read the entire manuscript. -

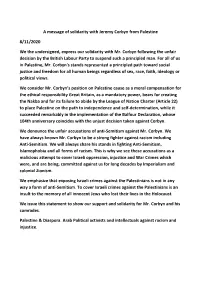

A Message of Solidarity with Jeremy Corbyn from Palestine 8/11/2020

A message of solidarity with Jeremy Corbyn from Palestine 8/11/2020 We the undersigned, express our solidarity with Mr. Corbyn following the unfair decision by the British Labour Party to suspend such a principled man. For all of us in Palestine, Mr. Corbyn's stands represented a principled path toward social justice and freedom for all human beings regardless of sex, race, faith, ideology or political views. We consider Mr. Corbyn’s position on Palestine cause as a moral compensation for the ethical responsibility Great Britain, as a mandatory power, bears for creating the Nakba and for its failure to abide by the League of Nation Charter (Article 22) to place Palestine on the path to independence and self-determination, while it succeeded remarkably in the implementation of the Balfour Declaration, whose 104th anniversary coincides with the unjust decision taken against Corbyn. We denounce the unfair accusations of anti-Semitism against Mr. Corbyn. We have always known Mr. Corbyn to be a strong fighter against racism including Anti-Semitism. We will always share his stands in fighting Anti-Semitism, Islamophobia and all forms of racism. This is why we see these accusations as a malicious attempt to cover Israeli oppression, injustice and War Crimes which were, and are being, committed against us for long decades by Imperialism and colonial Zionism. We emphasize that exposing Israeli crimes against the Palestinians is not in any way a form of anti-Semitism. To cover Israeli crimes against the Palestinians is an insult to the memory of all innocent Jews who lost their lives in the Holocaust. -

What Is the Relationship Between Church and State? Are These the Last Days?

The Crucial Questions Series By R. C. Sproul Who Is Jesus? Can I Trust the Bible? Does Prayer Change Things? Can I Know God’s Will? How Should I Live in This World? What Does It Mean to Be Born Again? Can I Be Sure I’m Saved? What Is Faith? What Can I Do with My Guilt? What Is the Trinity? What Is Baptism? Can I Have Joy in My Life? Who Is the Holy Spirit? Does God Control Everything? How Can I Develop a Christian Conscience? What Is the Lord’s Supper? What Is the Church? What Is Repentance? What Is the Relationship between Church and State? Are These the Last Days? What Is the Relationship between Church and State? © 2014 by R.C. Sproul Published by Reformation Trust Publishing A division of Ligonier Ministries 421 Ligonier Court, Sanford, FL 32771 Ligonier.org ReformationTrust.com Printed in North Mankato, MN Corporate Graphics July 2014 First edition All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the publisher, Reformation Trust Publishing. The only exception is brief quotations in published reviews. Cover design: Gearbox Studios Interior design and typeset: Katherine Lloyd, The DESK All Scripture quotations are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sproul, R. C. -

Parliament Special Edition

October 2016 22nd Issue Special Edition Our Continent Africa is a periodical on the current 150 Years of Egypt’s Parliament political, economic, and cultural developments in Africa issued by In this issue ................................................... 1 Foreign Information Sector, State Information Service. Editorial by H. E. Ambassador Salah A. Elsadek, Chair- man of State Information Service .................... 2-3 Chairman Salah A. Elsadek Constitutional and Parliamentary Life in Egypt By Mohamed Anwar and Sherine Maher Editor-in-Chief Abd El-Moaty Abouzed History of Egyptian Constitutions .................. 4 Parliamentary Speakers since Inception till Deputy Editor-in-Chief Fatima El-Zahraa Mohamed Ali Current .......................................................... 11 Speaker of the House of Representatives Managing Editor Mohamed Ghreeb (Documentary Profile) ................................... 15 Pan-African Parliament By Mohamed Anwar Deputy Managing Editor Mohamed Anwar and Shaima Atwa Pan-African Parliament (PAP) Supporting As- Translation & Editing Nashwa Abdel Hamid pirations and Ambitions of African Nations 18 Layout Profile of Former Presidents of Pan-African Gamal Mahmoud Ali Parliament ...................................................... 27 Current PAP President Roger Nkodo Dang, a We make every effort to keep our Closer Look .................................................... 31 pages current and informative. Please let us know of any Women in Egyptian and African Parliaments, comments and suggestions you an endless march of accomplishments .......... 32 have for improving our magazine. [email protected] Editorial This special issue of “Our Continent Africa” Magazine coincides with Egypt’s celebrations marking the inception of parliamentary life 150 years ago (1688-2016) including numerous func- tions atop of which come the convening of ses- sions of both the Pan-African Parliament and the Arab Parliament in the infamous city of Sharm el-Sheikh. -

•C ' CONFIDENTIAL EGYPT October 8, 1946 Section 1 ARCHIVE* J 4167/39/16 Copy No

THIS DOCUMENT IS THE PROPERTY OF HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY'S GOYERNMENT •C ' CONFIDENTIAL EGYPT October 8, 1946 Section 1 ARCHIVE* J 4167/39/16 Copy No. LEADING PERSONALITIES IN EGYPT Mr. Bowker to Mr. Bevin. (Received 8th October) (No. 1051. Confidential) 53. Ibrahim Abdul Hadi Pasha. Sir, Cairo, 30th September, 1946 54. Maitre Abdel Hamid Abdel Hakk. With reference to Mr. Farquhar's despatch 55. Nabil Abbas Halim. No. 1205 of-29th August, 1945, I have the honour 56. Maitre Ahmed Hamza. to transmit a revised list of personalities in Egypt. 57. Abdel Malek Hamza Bey. I have, &c. 58. El Lewa Mohammed Saleh Harb Pasha. JAMES BOWKEE. 59. Mahmoud Hassan Pasha. 60. Mohammed Abdel Khalek Hassouna Pasha. 61. Dr. Hussein Heikal Pasha. Enclosure 62. Sadek Henein Pasha. INDEX 63. Mahmoud Tewfik el-Hifnawi Pasha. 64. Neguib el-Hilaly Pasha. I.—Egyptian Personalitits 65. Ahmed Hussein Effendi. 1. Fuad Abaza Pasha. 66. Dr. Tahra Hussein. 2. Ibrahim Dessuki Abaza Pasha. 67. Dr. Ali Ibrahim Pasha, C.B.E. 3. Maitre Mohammed Fikri Abaza. 68. Kamel Ibrahim Bey. 4. Mohammed Ahmed Abboud Pasha. 69. Mohammed Hilmy Issa Pasha. 5. Dr. Hafez Afifi Pasha. 70. Aziz Izzet Pasha, G.C.V.O. 6. Abdel Kawi Ahmed Pasha. 71. Ahmed Kamel Pasha. 7. Ibrahim Sid Ahmed Bey. 72. ,'Lewa Ahmed Kamel Pasha. 8. Murad Sid Ahmed Pasha. 73. Ibrahim Fahmy Kerim Pasha. 9. Ahmed All Pasha, K.C.V.O. 74. Mahmoud Bey Khalil. 10. Prince Mohammed All, G.C.B., G.C.M.G. 75. Ahmed Mohammed Khashaba Pasha. 11. Tarraf Ali Pasha. -

Annales Islamologiques

MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE ANNALES ISLAMOLOGIQUES en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne AnIsl 50 (2016), p. 107-143 Mohamed Elshahed Egypt Here and There. The Architectures and Images of National Exhibitions and Pavilions, 1926–1964 Conditions d’utilisation L’utilisation du contenu de ce site est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Toute autre utilisation du site et de son contenu est soumise à une autorisation préalable de l’éditeur (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). Le copyright est conservé par l’éditeur (Ifao). Conditions of Use You may use content in this website only for your personal, noncommercial use. Any further use of this website and its content is forbidden, unless you have obtained prior permission from the publisher (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). The copyright is retained by the publisher (Ifao). Dernières publications 9782724708288 BIFAO 121 9782724708424 Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l'étranger (BAEFE) 9782724707878 Questionner le sphinx Philippe Collombert (éd.), Laurent Coulon (éd.), Ivan Guermeur (éd.), Christophe Thiers (éd.) 9782724708295 Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 30 Sylvie Marchand (éd.) 9782724708356 Dendara. La Porte d'Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724707953 Dendara. La Porte d’Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724708394 Dendara. La Porte d'Hathor Sylvie Cauville 9782724708011 MIDEO 36 Emmanuel Pisani (éd.), Dennis Halft (éd.) © Institut français d’archéologie orientale - Le Caire Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 1 / 1 MohaMed elshahed* Egypt Here and There The Architectures and Images of National Exhibitions and Pavilions, 1926–1964 • abstract In 1898 the first agricultural exhibition was held on the island of Gezira in a location accessed from Cairo’s burgeoning modern city center via the Qasr el-Nil Bridge. -

Personal Information Name: Mohamed Naguib Mohamed Date

C.V. Personal Name: Mohamed Naguib Mohamed information Date of birth: 2-6-1985 E-mail:- [email protected] [email protected] - Mobile : (+2)0111-6090451 Marital status: Married Education PhD in Microbiology Botany and Microbiology Department Faculty of Science Cairo University Giza, Egypt 2012-2016 Master degree in Microbiology Botany Department Cairo University Giza, Egypt 2007-2011 Bachelor of Science Cairo University Giza, Egypt 2002-2006 ThanaweyaAmma, Science Major El-Sayedia Giza, Egypt 1998-2001 Master degree Biodegradation of some Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by some title Soil fungi PhD degree title “Purification and characterization of laccase from some soil microorganisms” Professi onal 1- Teaching in Cairo University since 20 07 . Career 2- Biomap &Wallacea International operations Supervision 2008. Experience 3-Treasurer for the The Egyptian Botanical Society 2018. 4- Manager of IT unit in Faculty of Science, Cairo University 2018. 5- Executive manager in FLDC from 2015. 6- International Certified Professional Trainer from 2017. Attended 1- CIPT (Certified International Professional Trainer) course in 2017. Training 2- Executive Manager course from FLDC in 2015. Courses 3-Control lab. Of Oil &Soap Company from 1/7/2002 to 1/8/2002 4-Pharmacy Company from 1/7/2006 to 1/10/2006. 5-Molecular biology Practical Courses (PCR, Cloning ) in Animal reproduction research institute. 6- Molecular biology practi cal Courses for stuff members in Cairo University by HEEPF. 7- Biomap &Wallacea International British operations Training in 2006. 8-Faculty and leadership development center (FLDC) training courses a) Competing for research funds. b) Conference organization. c) The credit hour systems. -

Gladstonian Liberalism: a Catalyst for Social Representation and Democratic Reform in Victorian Britain

Pittsburg State University Pittsburg State University Digital Commons Electronic Thesis Collection Spring 5-12-2018 GLADSTONIAN LIBERALISM: A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL REPRESENTATION AND DEMOCRATIC REFORM IN VICTORIAN BRITAIN Jason Belcher Pittsburg State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pittstate.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Belcher, Jason, "GLADSTONIAN LIBERALISM: A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL REPRESENTATION AND DEMOCRATIC REFORM IN VICTORIAN BRITAIN" (2018). Electronic Thesis Collection. 244. https://digitalcommons.pittstate.edu/etd/244 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Pittsburg State University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Pittsburg State University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLADSTONIAN LIBERALISM: A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL REPRESENTATION AND DEMOCRATIC REFORM IN VICTORIAN BRITAIN A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of History Jason Samuel Belcher Pittsburg State University Pittsburg, Kansas March 2018 i GLADSTONIAN LIBERALISM: A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL REPRESENTATION AND DEMOCRATIC REFORM IN VICTORIAN BRITAIN Jason Samuel Belcher APPROVED: Thesis Advisor _______________________________________________ Dr. Michael Thompson, The department of History, Philosophy and Social Sciences -

By: 5151 EAST BROADWAY, SUITE 1500 TUCSON, ARIZONA 85711

FINAL ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT EGYPT WATER USE AND MANAGEMENT PROJECT CONTRACT NO. AID/NE-C-1551 TO: AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT By: . RICHARDSON M. E. QUENEMOEN H. R. HORSEY CONSORTIUM FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT 5151 EAST BROADWAY, SUITE 1500 TUCSON, ARIZONA 85711 FINAL ADMINISTRATIVE REPORT EGYPT WATER USE AND MANAGEMENT PROJECT CONTRACT NO. AID/NE-C-1351 TO: AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT By: E. V. RICHARDSON M. E. QUENEMOEN H. R. HORSEY CONSORTIUM FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT 5151 EAST BROADWAY, SUITE 1500 TUCSON, ARIZONA 85711 APRIL 1985 ABSTRACT The following report summarizes the objectives and accomplishments of the Egypt Water Use and Management Project during the period of its operation, 1977 to 1984. The project was instigated in 1977 through action of the Egyptian Government's Ministry of Irrigation, its Ministry of Agriculture and the United States Agency for International Development. Operation of the Project was conducted by the Consortium for International Development with Colorado State University as the lead university. The primary objective of the project was to increase the overall social and economic well-being of the small farmer farming the old alluvial lands within the Nile River Valley and Delta within Egypt. This objective was to be met through the development of an applied program of increased water use and management efficiency that would lead to increases in agricultural yields. The objective was approached through the initiation of surveys to identify problems at the farm level pertaining to the water application, delivery and drainage systems and related agronomic, social and economic conditions. Following this diagnostic analysis phase solution alternatives were developed and field tested regarding their technical and economic feasibility, and potential acceptance by both farmers and government. -

Methodist History, 57:4 (July 2019)

Methodist History, 57:4 (July 2019) Methodist History Volume LVII october, 2018-July, 2019 alfred t. day III, editor Published by General Commission on Archives and History The United Methodist Church Madison, New Jersey Contributors and articles Baker, Frank Probing a Wesley Letter . 172 Campbell, Ted A. The United Methodist Church Union Fifty Years Later: The Abiding Problems of a Modernist Vision of Union . 111 Cope, Rachel Introduction to “Susanna Wesley’s Spirituality: The Freedom of a Christian Woman” . 224 Davis, Jerry An Ecumenical “Moment”: St. Barnabas Church of Arlington, Texas, 1977–1986 . 175 Deichmann, Wendy J. “If God Calls, Dare We Falter?”: The Strategic Founding and Independence of the Woman’s Missionary Association of the Church of the United Brethren in Christ, 1869–1877 . 84 Kisker, Scott T. Unpopular Religion: Bishop Milton Wright and the United Brethren Schism of 1889 . 45 Leep, Mark F. The First Seeds of Virginia’s Sterilization Act of 1924: Joseph T. Mastin and the State Board of Charities and Corrections . 143 250 Contributors and Articles 251 Maldonado, Jr., David Remembering the Significance of My Home Church, La Trinidad Iglesia Metodista, Seguin: Personal Memories and Reflections . 241 O’Malley, J. Steven Merging the Streams: Pietism and Transatlantic Revival in the Colonial Era and the Birth of the Evangelical Association and the United Brethren in Christ . 8 Phelps, Benjamin T. A Confessional Lutheran Reaction to Methodism in America: The Case of Friedrich Wyneken . 153 Richey, Russell E. Repairing Episcopacy by Tracking that of Bishop Christian Newcomer . 26 Rogal, Samuel J. “Thy Secret Mind Infallible”: The Cast of Lots Among Leaders of Eighteenth-Century English Methodism . -

Fo#371/102704

.* a Kaference:- 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 I 1 COPYRIGHT - MOT TO BE REPRODUCED PHOTOGRAPH! CALLY WITHOUT PERMISSION \ Registry t No. vn.*^ 0 s Top Secret. Secret. Confidential. Restricted. Openn. t lisf o[ Draff. ietfe. ' U/e g -fcc Ul X c z ut a*Md tt w» if v* ' uu (A x, 3l- 0 •J M M TiutOUH I (/ 1 Tto F* fcMC r AFRICAN DEPARTMENT I J ,.. ' ' / ry— 4 Last Paper. (Minutes.) "ttu ^ References. (a) a»> 011'* no Afaor (Print.) (How ditpoaed of.) |kJlw<vn • ( S*IL pa/**»*pi K- jfl Lotion (Index.) J Next Paper. fc, *fr sum FO ( PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE Reference!- COPYRIGHT - HOT TO BE REPRODUCED PHOTOGRAPHICALLY WITHOUT PERMISSION _u Av^rxUrv~-x A x> /T AFRICAN DEPARTMENT J 1953 EGYPT AND SUDAN FROM d.C. C*0~t*<-t' e/ r < / / ~ 7 *fe/" *~ - ^ /s S~l~*—*-* s-t-f-~^- No. Dated Received in Registry — ^ References 1L « MEVUTES % M<*- ^ 4 fe 0 i- 'V.'o \ (How disposed of) Action ""- (ladez) ttipleted) CU5&JLV i»tv*?>s! wrt ?v.t A ' ? n a 6 Reference:- t 2 P^b^,'• — ' 7(• /1 j//O 3«C Vn^/ C* ^- ^^r^;Q^/V C — 7 / C*^SC O I 1 1 1 1 \ \ 1 COPYRIGHT - NOT TO BE REPRODUCED PHOTOGRAPHICALLY WITHOUT PERMISSION f , /^jLu* ^rte u I BRITISH EMBASSY, No. 12V(101lAl/53) CAIRO. CONFIDENTIAL Hist May, 1953• J Sir, In recent weeks opposition to the Array regime has revived and is now undoubtedly more widespread and outspoken than on the previous occasions in September and November of 1952 and in January and March of this year when counter-measures against hostile elements were taken by the Revolutionary Command (repressive in three of the four instances). -

General Index: <Em>Wesley and Methodist Studies</Em> Volumes 1–10

General Index Wesley and Methodist Studies Volumes 1–10 (2009–2018) Christopher D. Rodkey Guide to the Index Tis index covers the frst ten volumes of Wesley and Methodist Studies, beginning with the frst volume (2009) and ending with volume 10/2 (2018). Te editorial team is grateful to the Revd Dr Christopher D. Rodkey for design- ing and drafing the index, and to Fernando Carvalho for his editorial work. Te creation and production of such an index is highly complex. While names, places, and events are relatively straightforward to reference, Wesley and Methodist Studies covers theological and related topics that can be concep- tually challenging to organize. And the indexer is called upon also to make a wide range of contestable judgements, for example, in defning key terms such as ‘Methodist’. Users should therefore see the index as a guide rather than a detailed route map. Given the range and scope of the journal, the index focuses on substantive references to topics in the main body of the text; in general, incidental men- tions, and topics that appear only in footnotes, are not referenced. We would welcome receiving notifcations of index errors and omissions from readers. Geordan Hammond Clive Norris Wesley and Methodist Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2020 Copyright © 2020 Te Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA DOI: 10.5325/weslmethstud.12.1.0109 This content downloaded from 146.186.116.60 on Wed, 08 Jan 2020 18:40:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 110 wesley and methodist studies Contributors and Articles Atherstone, Andrew Evangelical Dissentients and the Defeat of the Anglican-Methodist Unity Scheme, 7:100–116 Bebbington, D.