Review the Implementation, of Laws and Policies Related to Trafficking: Towards an Effective Rescue and Post-Rescue Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Criminal Investigation Department Govt

a -. !h ii Criminal Investigation Department Govt. of West Bengal. Bhabani Bh aban, Alipore, Kolkata - 700.027.. "Tender for purchase of "Photographic Materials" of clD, west Bengal for the financial year 2015-16." Tender Year .201 5 - 2010. Tender Notice No. : 051 2015-10 /ClD /WB. closinq Date : 7 (seven) days after publication. rENpqF NorlqE The Criminal Investigation Department, West Bengal, Bhabani Bhawan, Alipore, Kolkata - 700027 , invites sealed Tenders from private firms for purchase Photography materials of ClD, West Bengal. l. SPECIFICATION OF ITEMS :- Photographic materials for CID, West Bengal. (Details list may be collected by the bidders from O/S, Police Office, CID. West Bengal or CID Website, www.cidwestbengal.gov.in.) 2. SCHEDULE:- A' Closing and Opening Date: 7 (Seven) days after publications Time 14.00 hrs. 3. SU.BMISSION OF BID :- I. Bidders may collect / download the Tender document from CID Website, www.cidwestbengal.eov.in. The bidders may remain present at the time of opening of tenders. il. Prices quoted, shall be including all taxes not to be exceed MRp. The quotations should be submitted in envelopes duly sealed and properly super scribed with name and address of the firms and "Tender No- 05l}0l5- l6/CID/WB and Tenders from private firms for purchase of "Photographic materials" It must be addressed to the ADG, cID, west Bengal, Bhabani Bhawan, Alipore, Kolkata-700027, and must be sent to this office on or before the closing time for submission of tenders. In case the quotations are received without sealed cover, the tender will be liable to be cancelled. -

Comp. Sl. No Name S/D/W/O Designation & Office Address Date of First Application (Receving) Basic Pay / Pay in Pay Band Type

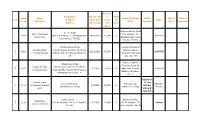

Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. Name Name & Address Roster Date of Date of Sl. No. & Office Application Pay in of Status Sl. No S/D/W/O D.D.O. Category Birth Retirement Address (Receving) Pay Flat Band Accounts Officer, 9D & Gr. - II Sister Smt. Anita Biswas B.G. Hospital , 57, 1 1879 9D & B.G. Hospital , 57, Beleghata Main 28/12/2012 21,140 A ALLOTTED Sri Salil Dey Beleghata Main Road, Road, Kolkata - 700 010 Kolkata - 700 010 District Fishery Officer Assistant Director of Bikash Mandal O/O the Deputy Director of Fisheries, Fisheries, Kolkata 2 1891 31/12/2012 22,500 A ALLOTTED Lt. Joydev Mandal Kolkata Zone, 9A, Esplanade East, Kol - Zone, 9A, Esplanade 69 East , Kol - 69 Asstt. Director of Fishery Extn. Officer Fisheries, South 24 Swapan Kr. Saha O/O The Asstt. Director of Fisheries 3 1907 1/1/2013 17,020 A Pgns. New Treasury ALLOTTED Lt. Basanta Saha South 24 Pgs., Alipore, New Treasury Building (6th Floor), Building (6th Floor), Kol - 27 Kol - 27 Eligible for Samapti Garai 'A' Type Assistant Professor Principal, Lady Allotted '' 4 1915 Sri Narayan Chandra 2/1/2013 20,970 A flats but Lady Brabourne College Brabourne College B'' Type Garai willing 'B' Type Flat Staff Nurse Gr. - II Accounts Officer, Lipika Saha 5 1930 S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, A.J.C. Bose Rd. , 4/1/2013 16,380 A S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, Allotted Sanjit Kumar Saha Kol -20 A.J.C. Bose Rd. , Kol -20 Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. -

CID West Bengal

Registered No. C_603 No. – 09 of 2017 CID West Bengal Criminal Intelligence Gazette Property of the Government of West Bengal Published by Authority. Kolkata September - 2017 BS - 1424 Part - I Special Notice: Nil Part – II (A) Persons wanted in specific cases: - Reference:- Bhaktinagar PS Case No. 1444/15 dated 13.10.15 u/s 20(b)(ii)(c)/23/25 NDPS Act. Shown beside the picture of the following accused person namely Shyam Limbu s/o Som Bahadur Limbu of village Shanti Nagar, PS Bhudwara, District Jhapa, Nepal was convicted in c/w the above 1. noted case. The accused person escaped from Sadar Court Hazat Jalpaiguri on 15.9.17. D/R Age approx 27 years, Ht. 5’-3”, complexion fair, built slim, two mole on his right side of the bally. All concerned are requested if any information found about the accused person please contact to the Superintendent of Jalpaiguri central correctional home and superintendent of Police Jalpaiguri. Reference:- Madanriting PS Case No. 79/(8)2017 u/s 3/4/5/6 prevention of immoral trafficking Act r/w section 3(a)/4/17 of POCSO Act. 2. Shown beside the picture of the following accused person namely Samir Dey s/o not noted of East Khasi hills, Shillong is wanted in c/w the above noted case. All concerned are requested if any information found about the accused person please contact to the Superintendent of Police East Khasi hills, Shillong. (B) Persons arrested who may be wanted elsewhere: - Nil. 2 (C) (i) Important arrest and property found in the possession of arrested persons with reference to NDPS Act :- Sl. -

Combating Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia

CONTENTS COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA Regional Synthesis Paper for Bangladesh, India, and Nepal APRIL 2003 This book was prepared by staff and consultants of the Asian Development Bank. The analyses and assessments contained herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Asian Development Bank, or its Board of Directors or the governments they represent. The Asian Development Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this book and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. i CONTENTS CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS vii FOREWORD xi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY xiii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 UNDERSTANDING TRAFFICKING 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Defining Trafficking: The Debates 9 2.3 Nature and Extent of Trafficking of Women and Children in South Asia 18 2.4 Data Collection and Analysis 20 2.5 Conclusions 36 3 DYNAMICS OF TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA 39 3.1 Introduction 39 3.2 Links between Trafficking and Migration 40 3.3 Supply 43 3.4 Migration 63 3.5 Demand 67 3.6 Impacts of Trafficking 70 4 LEGAL FRAMEWORKS 73 4.1 Conceptual and Legal Frameworks 73 4.2 Crosscutting Issues 74 4.3 International Commitments 77 4.4 Regional and Subregional Initiatives 81 4.5 Bangladesh 86 4.6 India 97 4.7 Nepal 108 iii COMBATING TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND CHILDREN 5APPROACHES TO ADDRESSING TRAFFICKING 119 5.1 Stakeholders 119 5.2 Key Government Stakeholders 120 5.3 NGO Stakeholders and Networks of NGOs 128 5.4 Other Stakeholders 129 5.5 Antitrafficking Programs 132 5.6 Overall Findings 168 5.7 -

The Indian Police Journal Vol

Vol. 63 No. 2-3 ISSN 0537-2429 April-September, 2016 The Indian Police Journal Vol. 63 • No. 2-3 • April-Septermber, 2016 BOARD OF REVIEWERS 1. Shri R.K. Raghavan, IPS(Retd.) 13. Prof. Ajay Kumar Jain Former Director, CBI B-1, Scholar Building, Management Development Institute, Mehrauli Road, 2. Shri. P.M. Nair Sukrali Chair Prof. TISS, Mumbai 14. Shri Balwinder Singh 3. Shri Vijay Raghawan Former Special Director, CBI Prof. TISS, Mumbai Former Secretary, CVC 4. Shri N. Ramachandran 15. Shri Nand Kumar Saravade President, Indian Police Foundation. CEO, Data Security Council of India New Delhi-110017 16. Shri M.L. Sharma 5. Prof. (Dr.) Arvind Verma Former Director, CBI Dept. of Criminal Justice, Indiana University, 17. Shri S. Balaji Bloomington, IN 47405 USA Former Spl. DG, NIA 6. Dr. Trinath Mishra, IPS(Retd.) 18. Prof. N. Bala Krishnan Ex. Director, CBI Hony. Professor Ex. DG, CRPF, Ex. DG, CISF Super Computer Education Research Centre, Indian Institute of Science, 7. Prof. V.S. Mani Bengaluru Former Prof. JNU 19. Dr. Lalji Singh 8. Shri Rakesh Jaruhar MD, Genome Foundation, Former Spl. DG, CRPF Hyderabad-500003 20. Shri R.C. Arora 9. Shri Salim Ali DG(Retd.) Former Director (R&D), Former Spl. Director, CBI BPR&D 10. Shri Sanjay Singh, IPS 21. Prof. Upneet Lalli IGP-I, CID, West Bengal Dy. Director, RICA, Chandigarh 11. Dr. K.P.C. Gandhi 22. Prof. (Retd.) B.K. Nagla Director of AP Forensic Science Labs Former Professor 12. Dr. J.R. Gaur, 23 Dr. A.K. Saxena Former Director, FSL, Shimla (H.P.) Former Prof. -

Child Trafficking in India

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Fifth Annual Interdisciplinary Conference on Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Human Trafficking 2013 Trafficking at the University of Nebraska 10-2013 Wither Childhood? Child Trafficking in India Ibrahim Mohamed Abdelfattah Abdelaziz Helwan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/humtrafcon5 Abdelaziz, Ibrahim Mohamed Abdelfattah, "Wither Childhood? Child Trafficking in India" (2013). Fifth Annual Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Trafficking 2013. 6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/humtrafcon5/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Trafficking at the University of Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fifth Annual Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Trafficking 2013 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Wither Childhood? Child Trafficking in India Ibrahim Mohamed Abdelfattah Abdelaziz This article reviews the current research on domestic trafficking of children in India. Child trafficking in India is a highly visible reality. Children are being sold for sexual and labor exploitation, adoption, and organ harvesting. The article also analyzes the laws and interventions that provide protection and assistance to trafficked children. There is no comprehensive legislation that covers all forms of exploitation. Interven- tions programs tend to focus exclusively on sex trafficking and to give higher priority to rehabilitation than to prevention. Innovative projects are at a nascent stage. Keywords: human trafficking, child trafficking, child prostitution, child labor, child abuse Human trafficking is based on the objectification of a human life and the treat- ment of that life as a commodity to be traded in the economic market. -

Compendium of Best Practices on Anti Human Trafficking

Government of India COMPENDIUM OF BEST PRACTICES ON ANTI HUMAN TRAFFICKING BY NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS Acknowledgments ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ms. Ashita Mittal, Deputy Representative, UNODC, Regional Office for South Asia The Working Group of Project IND/ S16: Dr. Geeta Sekhon, Project Coordinator Ms. Swasti Rana, Project Associate Mr. Varghese John, Admin/ Finance Assistant UNODC is grateful to the team of HAQ: Centre for Child Rights, New Delhi for compiling this document: Ms. Bharti Ali, Co-Director Ms. Geeta Menon, Consultant UNODC acknowledges the support of: Dr. P M Nair, IPS Mr. K Koshy, Director General, Bureau of Police Research and Development Ms. Manjula Krishnan, Economic Advisor, Ministry of Women and Child Development Mr. NS Kalsi, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs Ms. Sumita Mukherjee, Director, Ministry of Home Affairs All contributors whose names are mentioned in the list appended IX COMPENDIUM OF BEST PRACTICES ON ANTI HUMAN TRAFFICKING BY NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS © UNODC, 2008 Year of Publication: 2008 A publication of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Regional Office for South Asia EP 16/17, Chandragupta Marg Chanakyapuri New Delhi - 110 021 www.unodc.org/india Disclaimer This Compendium has been compiled by HAQ: Centre for Child Rights for Project IND/S16 of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Regional Office for South Asia. The opinions expressed in this document do not necessarily represent the official policy of the Government of India or the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. The designations used do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or of its authorities, frontiers or boundaries. -

A Report on Trafficking in Women and Children in India 2002-2003

NHRC - UNIFEM - ISS Project A Report on Trafficking in Women and Children in India 2002-2003 Coordinator Sankar Sen Principal Investigator - Researcher P.M. Nair IPS Volume I Institute of Social Sciences National Human Rights Commission UNIFEM New Delhi New Delhi New Delhi Final Report of Action Research on Trafficking in Women and Children VOLUME – 1 Sl. No. Title Page Reference i. Contents i ii. Foreword (by Hon’ble Justice Dr. A.S. Anand, Chairperson, NHRC) iii-iv iii. Foreword (by Hon’ble Mrs. Justice Sujata V. Manohar) v-vi iv. Foreword (by Ms. Chandani Joshi (Regional Programme Director, vii-viii UNIFEM (SARO) ) v. Preface (by Dr. George Mathew, ISS) ix-x vi. Acknowledgements (by Mr. Sankar Sen, ISS) xi-xii vii. From the Researcher’s Desk (by Mr. P.M. Nair, NHRC Nodal Officer) xii-xiv Chapter Title Page No. Reference 1. Introduction 1-6 2. Review of Literature 7-32 3. Methodology 33-39 4. Profile of the study area 40-80 5. Survivors (Rescued from CSE) 81-98 6. Victims in CSE 99-113 7. Clientele 114-121 8. Brothel owners 122-138 9. Traffickers 139-158 10. Rescued children trafficked for labour and other exploitation 159-170 11. Migration and trafficking 171-185 12. Tourism and trafficking 186-193 13. Culturally sanctioned practices and trafficking 194-202 14. Missing persons versus trafficking 203-217 15. Mind of the Survivor: Psychosocial impacts and interventions for the survivor of trafficking 218-231 16. The Legal Framework 232-246 17. The Status of Law-Enforcement 247-263 18. The Response of Police Officials 264-281 19. -

Laws Protecting Sex Worker & Condition of Sex Worker

© 2021 JETIR June 2021, Volume 8, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) LAWS PROTECTING SEX WORKER & CONDITION OF SEX WORKER DURING LOCKDOWN RISHAB KUMAR, 4th year student at UPES, Dheradun. Contact no.- 9719942006, Dheradun, Uttrakhand, INDIA ABSTRACT Sex work many times considered by images of compulsion, poverty, insolvency and lack of agency and sex worker as merely being oppressed victims of society and they were treat bias as compare to other group of society and during lockdown in the country sex worker face this type of biasness in this paper I will discuss about this biasness and problems faced by the sex worker during lockdown and then how supreme court take steps to protect the sex worker during pandemic. My research highlights the history of the prostitution in India that how the prostitution is evolved and how this sector is prominent in history of India. This research also highlight what legislation make by the government to protect the sex worker and the some laws to prohibit the trafficking of women and girl child in the prostitution and the problems faces by the sex worker and the possible solution to the problems. And the most important question will discuss in that research paper shall India legalize prostitution? Key words – Sex worker, legislation, Covid-19, Pandemic. TABLE OF CONTENT Page no. 1. INTRODUCTION 2. History of prostitution 3. Legislation on the sex worker 4. Shall India legalize prostitution 5. Condition of sex worker during lockdown 6. Conclusion 7. References JETIR2106255 Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research (JETIR) www.jetir.org b800 © 2021 JETIR June 2021, Volume 8, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) INTRODUCTION Prostitution is deemed to be the oldest profession and trases of this profession was found in ancient Babylons1. -

Trafficking of Minor Girls for Commercial Sexual Exploitation in India: a Synthesis of Available Evidence

report TRAFFICKING OF MINOR GIRLS FOR COMMERCIAL SEXUAL EXPLOITATION IN INDIA: A SYNTHESIS OF AVAILABLE EVIDENCE K G Santhya Shireen J Jejeebhoy Sharmistha Basu Zone 5A, Ground Floor India Habitat Centre, Lodi Road New Delhi, India 110003 Phone: 91-11-24642901 Email: [email protected] ugust 2014 popcouncil.org A The Population Council confronts critical health and development issues—from stopping the spread of HIV to improving reproductive health and ensuring that young people lead full and productive lives. Through biomedical, social science, and public health research in 50 countries, we work with our partners to deliver solutions that lead to more effective policies, programs, and technologies that improve lives around the world. Established in 1952 and headquartered in New York, the Council is a nongovernmental, nonprofit organization governed by an international board of trustees. Population Council Zone 5A, Ground Floor India Habitat Centre, Lodi Road New Delhi, India 110003 Phone: 91-11-24642901 Email: [email protected] Website: www.popcouncil.org Suggested citation: Santhya, K G, S J Jejeebhoy and S Basu. 2014. Trafficking of Minor Girls for Commercial Sexual Exploitation in India: A Synthesis of Available Evidence. New Delhi: Population Council. TRAFFICKING OF MINOR GIRLS FOR COMMERCIAL SEXUAL EXPLOITATION IN INDIA: A SYNTHESIS OF AVAILABLE EVIDENCE K G Santhya Shireen J Jejeebhoy Sharmistha Basu ii Table of Contents List of Tables v Acknowledgements vii Chpater 1 Introduction 1 Chpater 2 Laws, policies and programmes -

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES 21 Century

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES st 21 Century Programme : EPISODE # 121 : SCRIPT FOR SHOWS WITHOUT ANCHOR/PRESENTER MUSIC (14”) ANNOUNCEMENT Today on 21st Century ….. Girls for Sale in India And Canada’s indigenous women – the missing and the dead (11”) VIDEO INTRO – INDIA: GIRLS FOR SALE NARRATION In India – a child is abducted every 8 minutes. Most are girls. A third are never found. NOOR’S FATHER (In Hindi) If the child dies it is easier. If she goes missing, it’s more painful NARRATION Rescuing girls for sale. (23”) TITLE SLATE INDIA: GIRLS FOR SALE (4”) INDIA : GIRLS FOR SALE (TRT 12’24”) VIDEO AUDIO SHOTS OF HOWRAH NARRATION BRIDGE AND Kolkata - one of the largest cities in India. It’s home to one PROSTITUTES IN RED LIGHT AREA of the biggest red light districts in Asia. Over 60,000 prostitutes work here – many of them children, trafficked against their will. (16”) Rishi Kant, is an anti-trafficking activist. His mission is to rescue underage girls who have been kidnapped and RISHI IN TRAVELLING then sold into prostitution, forced marriage or domestic CAR slavery. (12”) UPSOUND/ RISHI KANT RISHI KANT (In English) Somebody identifies the girl, somebody procures the girl, brings her out from the village and take her to the railway station or bus station, from there they are transported to bigger cities. Once the girl is sent to Delhi or Mumbai, they are trapped. (19”) NARRATION Today, he’s on his way to meet the parents of a 17 year old girl, Noor Banu, who disappeared almost a year ago. -

Preventing and Combating the Trafficking of Girls in India Using Legal Empowerment Strategies Copyright © International Development Law Organization 2011

Preventing and Combating the Trafficking of Girls in India Using Legal Empowerment Strategies A Rights Awareness and Legal Assistance Program in Four Districts of West Bengal June 2010 – March 2011 Preventing and Combating the Trafficking of Girls in India Using Legal Empowerment Strategies Copyright © International Development Law Organization 2011 International Development Law Organization (IDLO) IDLO is an intergovernmental organization that promotes legal, regulatory and institutional reform to advance economic and social development in transitional and developing countries. Founded in 1983 and one of the leaders in rule of law assistance, IDLO's comprehensive approach achieves enduring results by mobilizing stakeholders at all levels of society to drive institutional change. Because IDLO wields no political agenda and has deep expertise in different legal systems and emerging global issues, people and interest groups of diverse backgrounds trust IDLO. It has direct access to government leaders, institutions and multilateral organizations in developing countries, including lawyers, jurists, policymakers, advocates, academics and civil society representatives. Among its activities, IDLO conducts timely, focused and comprehensive research in areas related to sustainable development in the legal, regulatory, and justice sectors. Through such research, IDLO seeks to contribute to existing Practice and scholarship on priority legal issues, and to serve as a conduit for the global exchange of ideas, best practices and lessons learned. IDLO produces a variety of professional legal tools covering interdisciplinary thematic and regional issues; these include book series, country studies, research reports, policy papers, training handbooks, glossaries and benchbooks. Research for these publications is conducted independently with the support of its country offices and in cooperation with international and national partner organizations.