Transportation Law Journal Denver

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

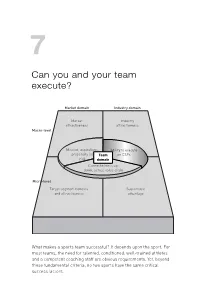

Can You and Your Team Execute?

Chapter7.qxd 28/4/06 2:10 pm Page 147 7 Can you and your team execute? Market domain Industry domain Market Industry attractiveness attractiveness Macro-level Mission, aspirations, AbilityAbility to to execute execute propensity for Team onon CSFs CSFs risk domain Connectedness up, down, across value chain Micro-level Target segment benefits Sustainable and attractiveness advantage What makes a sports team successful? It depends upon the sport. For most teams, the need for talented, conditioned, well-trained athletes and a competent coaching staff are obvious requirements. Yet, beyond these fundamental criteria, no two sports have the same critical success factors. Chapter7.qxd 28/4/06 2:10 pm Page 148 Take for example basketball, football and polo. Successful basketball teams must have players with the hand-eye coordination to shoot the ball accurately. Having tall players doesn’t hurt, either, of course. On the other hand, football (soccer) is played largely with the feet, so hand–eye coordination doesn’t matter very much. Agility and an ability to control the ball while keeping one’s head and eyes up are critical, however. A polo team’s success depends on both the athletes and the horses. As in basketball and football, the athletes need to have a good shot, but they must also be able to make this shot while riding a horse at high speed. In all three sports, endurance also matters – the fittest team often wins. In each of these sports, different factors are critical to success. Height and shooting ability make a big difference in basketball. Foot skills and the ability to maintain possession of the ball are important in football. -

The Custom Bicycle

THE CUSTOM BICYCLE Michae J. Kolin and Denise M.de la Rosa BUYING. SETTING UP, AND RIDING THE QUALITY BICYCLE Copyright© 1979 by Michael J. Kolin and Denise M. de la Rosa All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. Book Design by T. A. Lepley Printed in the United States of America on recycled paper, containing a high percentage of de-inked fiber. 468 10 9753 hardcover 8 10 9 7 paperback Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Kolin, Michael J The custom bicycle. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Bicycles and tricycles—Design and construction. 2. Cycling. I. De la Rosa, Denise M., joint author. II. Title. TL410.K64 629.22'72 79-1451 ISBN 0-87857-254-6 hardcover ISBN 0-87857-255-4 paperback THE CUSTOM BICYCLE BUYING, SETTING UP, AND RIDING i THE QUALITY BICYCLE by Michael J. Kolin and Denise M. de la Rosa Rodale Press Emmaus, Pa. ARD K 14 Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Part I Understanding the Bicycle Frame CHAPTER 1: The Bicycle Frame 1 CHAPTER 2: Bicycle Tubing 22 CHAPTER 3: Tools for Frame Building 3 5 Part II British Frame Builders CHAPTER 4: Condor Cycles 47 CHAPTER 5: JRJ Cycles, Limited 53 CHAPTER 6: Mercian Cycles, Limited BO CHAPTER 7: Harry Quinn Cycles, Limited 67 CHAPTER 8: Jack Taylor Cycles 75 CHAPTER 9: TI Raleigh, Limited 84 CHAPTER 10: Woodrup Cycles 95 Part III French Frame Builders CHAPTER 11: CNC Cycles 103 CHAPTER 12: Cycles Gitane 106 CHAPTER 13: Cycles Peugeot 109 THE CUSTOM BICYCLE Part IV Italian Frame Builders CHAPTER 14: Cinelli Cino & C. -

Catalog Price $4.00

CATALOG PRICE $4.00 Michael E. Fallon / Seth E. Fallon COPAKE AUCTION INC. 266 Rt. 7A/East Main Street - Box 47, Copake, N.Y. 12516 PHONE (518) 329-1142 FAX (518) 329-3369 Email: [email protected] - Website: www.copakeauction.com 27th Annual Antique & Classic Bicycle Auction Auction: Saturday April 21, 2018 at 9AM Swap Meet: Friday April 20 (6AM ‘til Dusk) Preview: Thur. April 19, 11-5PM – Fri. April 20, 11-5PM - Sat. April 21, 8-9AM TERMS: Everything sold “as is”. No condition reports in descriptions. Bidder must look over every lot to determine condition and authenticity. Cash or Travelers Checks - MasterCard, Visa and Discover Accepted * First time buyers cannot pay by check without a bank letter of credit * 18% buyer's premium, 23% buyer’s premium for LIVEAUCTIONEERS, INVALUABLE & AUCTIONZIP online purchases. National Auctioneers Association CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. Some of the lots in this sale are offered subject to a reserve. This reserve is a confidential minimum price agreed upon by the consignor & COPAKE AUCTION below which the lot will not be sold. In any event when a lot is subject to a reserve, the auctioneer may reject any bid not adequate to the value of the lot. 2. All items are sold “as is” and neither the auctioneer nor the consignor makes any warranties or representations of any kind with respect to the items, and in no event shall they be responsible for the correctness of the catalogue or other description of the physical condition, size, quality, rarity, importance, medium, provenance, period, source, origin or historical relevance of the items and no statement anywhere, whether oral or written, shall be deemed such a warranty or representation. -

The Effect of School Closure On

One link in the chain: Vancouver's independent bicycle dealers in the context of the globalized bicycle production network by Darcy McCord B.A. (Canadian Studies), Trent University, 2006 Research Project Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Urban Studies in the Urban Studies Program Faculty of Arts and Social Science Darcy McCord 2013 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2013 Approval Name: Darcy McCord Degree: Master of Urban Studies Title of Thesis: One link in the chain: Vancouver's independent bicycle dealers in the context of the globalized bicycle production network Examining Committee: Chair: Patrick J. Smith Professor, Urban Studies and Political Science Simon Fraser University Peter V. Hall Senior Supervisor Associate Professor, Urban Studies Simon Fraser University Karen Ferguson Supervisor Associate Professor, Urban Studies and History Simon Fraser University Paul Kingsbury External Examiner Associate Professor, Geography Simon Fraser University Date Defended/Approved: July 24, 2013 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Ethics Statement The author, whose name appears on the title page of this work, has obtained, for the research described in this work, either: a. human research ethics approval from the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics, or b. advance approval of the animal care protocol from the University Animal Care Committee of Simon Fraser University; or has conducted the research c. as a co-investigator, collaborator or research assistant in a research project approved in advance, or d. as a member of a course approved in advance for minimal risk human research, by the Office of Research Ethics. A copy of the approval letter has been filed at the Theses Office of the University Library at the time of submission of this thesis or project. -

World Bank Document

Ios4I INDUSTRYAND ENERGYDEPARTMENT WORKING PAPER INDUSTRYSERIES PAPER No. 23 Public Disclosure Authorized Buyer-SellerLinks for ExportDevelopment /1 March 1990 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Industryand Energy Department,PRE BUYERELLER LINKS IN. EXPORTUDEVELOPMENT Mrn1990''1 Industry DevelopmentDivision Industry and Energy Department Policy,Research and External Affairs BUYER-SELLER LINKS IN EXPORT DEVELOPMENT March 1990 Industry Development Division Industry and Energy Department Policy, Research and External Affairs TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. ABSTRACT . ........................................................ i I. INTRODUClION .1 II. THE INSEPARABLE TRLD: PRICE, QUALITY AND DELIVERY 3 A. Price ........ .................... 3 B. Quality. 3 C. Delivery. 4 III. RELATIONSHIPS.. 5 A. Buyer Motivation in Long Term Relationships .5 B. Gains for Suppliers. 6 C. Not All Relationships Are Long Term and Not All Long Term Relationships Are Close. 8 IV. HOW BUYER-SELLER RELATIONSHIPS ARE FORMED .11 A. The Ideal Sup,-tier .11 B. Sources of Information Aoout Suppliers .11 I.The Role of Country Reputation in Supplier Choice .13 V. CHANGING RELATIONSHIPS .15 A. Traditional Buyers .15 B. NIE Firms as Partners and Intermediaries: A New Trend .16 VI. IMPLICATIONS FOR EXPORT MARKETING STRATEGIES . .19 A What Suppliers Need to Do for Themselves .19 B. Public Efforts Supplement and Firm's Export Marketing Efforts .19 This report was written by Mary Lou Egan (consultart) and Ashoka Mody (IENIN). For comments and help, the authors are grateful to Nancy Barry, Carl Dahlman, Stephanie Gerard, Arvind Gupta, Kevin Young and Robert Wade. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the World Bank or its affiliates. -

Bicycle and Motorcycle Dynamics - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 16/1/22 上午 9:00

Bicycle and motorcycle dynamics - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 16/1/22 上午 9:00 Bicycle and motorcycle dynamics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bicycle and motorcycle dynamics is the science of the motion of bicycles and motorcycles and their components, due to the forces acting on them. Dynamics is a branch of classical mechanics, which in turn is a branch of physics. Bike motions of interest include balancing, steering, braking, accelerating, suspension activation, and vibration. The study of these motions began in the late 19th century and continues today.[1][2][3] Bicycles and motorcycles are both single-track vehicles and so their motions have many fundamental attributes in common and are fundamentally different from and more difficult to study than other wheeled vehicles such as dicycles, tricycles, and quadracycles.[4] As with unicycles, bikes lack lateral stability when stationary, and under most circumstances can only remain upright when moving forward. Experimentation and mathematical analysis have shown that a bike A computer-generated, simplified stays upright when it is steered to keep its center of mass over its model of bike and rider demonstrating wheels. This steering is usually supplied by a rider, or in certain an uncontrolled right turn. circumstances, by the bike itself. Several factors, including geometry, mass distribution, and gyroscopic effect all contribute in varying degrees to this self-stability, but long-standing hypotheses and claims that any single effect, such as gyroscopic or trail, is solely responsible for the stabilizing force have been discredited.[1][5][6][7] While remaining upright may be the primary goal of beginning riders, a bike must lean in order to maintain balance in a turn: the higher the speed or smaller the turn radius, the more lean is required. -

De Bicicleta)

NÃO TEMOS NADA A PERDER, EXCETO NOSSAS CORRENTES (DE BICICLETA): CONTEMPLANDO O FUTURO DO CICLOATIVISMO E DO CARRO1 ZACK FURNESS2 SOLUÇÃO DO SÉCULO XIX PARA PROBLEMAS DO SÉCULO XXI Não permitamos que interesses particulares egoístas ou que entusias- tas cabeludos bem-intencionados dificultem a marcha do progresso do transporte motorizado e muito menos que nos levem de volta ao tempo dos cavalos e das charretes. (Thomas P. Henry, “Discurso para o Encontro Anual dos Conselheiros da Associação Automobilística Americana”, 1936) Senhoras e senhores, eu lhes apresento os Democratas, promovendo soluções do século XIX para problemas do século XXI. Se vocês não gostam disso, andem de bicicleta. Se vocês não gostam do preço dos combustíveis, andem de bicicleta. Preparem-se para a próxima grande ideia dos Democratas: melhorar a eficiência energética por meio do cavalo e da charrete. (Patrick McHenry, Congressista da Carolina do Norte, 2007) 1 Este artigo é uma adaptação da conclusão do livro do autor One Less Car: Bicycling and the Politics of Automobility, originalmente publicado pela Temple UniversityPress (http://www.temple.edu/tempress/titles/1899_reg.html), a qual autoriza sua publica- ção. Tradução de Rodrigo Carlos da Rocha (doutorando em Antropologia Social pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Antropologia Social da Universidade de Brasília) e Renata Florentino (Doutoranda em Ciências Sociais pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Sociais da Universidade Estadual de Campinas). 2 Professor assistente de Comunicações na Pennsylvania State University Greater Allegheny, Estados Unidos. NÃO TEMOS NADA A PERDER, EXCETO NOSSAS CORRENTES... Zack Furnes 122 O Congressista dos Estados Unidos Patrick McHenry, represen- tante republicano pelo 10º Distrito Congressional da Carolina do Norte, discursou brevemente para a Câmara dos Representantes em 04 de agosto de 2007 em uma tentativa de encorajar votos contrários a um projeto de lei sobre energia renovável (Resolu- ção n. -

Book of Abstracts

Front cover: “Levende Etalage Dag”, A view of the wall at Pluympot, Delft, April 2010. A Bicycle in Mosaic, a photo made by Shirley Elprama. Contents Preface ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Scientific and Organizing Committees ....................................................................................... 8 Sponsors ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Program ....................................................................................................................................... 9 More info about Venue, Wireless Network, Contact and Addresses ........................................ 16 Abstracts..................................................................................................................................... 17 Rider Control of a Motorcycle near to its Cornering Limits R. S. Sharp - University of Surrey, United Kingdom ................................................................. 18 Analysis of the Biomechanical Interaction between Rider and Motorcycle by Means of an Active Rider Model Valentin Keppler - Biomotion Solutions, Germany ................................................................... 20 Modeling Manually Controlled Bicycle Maneuvers Ronald Hess, Jason K. Moore, Mont Hubbard and Dale L. Peterson, University of California, Davis, USA ................................................................................................................................ -

Norman Rockwell Business Papers, 1918-1978 ST.1976.20029 Finding Aid Prepared by Venus Van Ness and Jessika Drmacich

Norman Rockwell business papers, 1918-1978 ST.1976.20029 Finding aid prepared by Venus Van Ness and Jessika Drmacich Norman Rockwell Museum Archives-Studio Collection Processed in 2011 9 Glendale Road Stockbridge, Massachusetts, 01262 413-931-2212 [email protected] Norman Rockwell business papers, 1918-1978 ST.1976.20029 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical note...........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................7 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................8 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 General correspondence...........................................................................................................................9 -

Request Logs for Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC)

Description of document: Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Logs for Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC), 2010-2011 Requested date: 28-April-2011 Released date: 27-June-2011 Posted date: 05-March-2012 Date/date range of document: 01-October-2010 – 28-April-2011 Source of document: Disclosure Officer Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation 1200 K Street, N.W., Suite 11101 Washington, D.C. 20005 Fax: (202) 326-4042 (Attn: Disclosure Officer) The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. f,V(\ PBGC Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation Protecting America's Pensions 1200 K Street, N.W. , Washington, D.C. -

IMC Initiative EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TABLE of CONTENTS

IMC Initiative EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS We strive to create a campaign for Giant’s women’s line, Liv, that will SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS create awareness and brand loyalty among our most common audience Company Analysis which is within the demographic 25 to 40 years old, most of whom are inter- Product Analysis ested in sports and health. However, this campaign also applies to beginners Competitive Analysis as the women’s bike is built in such way that is easy to handle and is a good SWOT Analysis way to exercise and use for transportation. The campaign will be successful Current Consumer Analysis as it is mainly nationwide and divided tactically both within distribution of dif- ferent medias and specifically focusing on the major biking seasons within STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES different states. More specifically, we propose a marketing strategy in differ- Marketing Objective ent medias but mostly within women’s health magazines and social media. IMC Objective The social media will for the most part be Instagram, Snapchat and Facebook but with an opportunity to expand to Twitter etc. When advertising MESSAGE STRATEGY on social media, the users would use the hashtag #howILIV when posting a Creative Brief picture to show Individually and who you are. The rationale that the person who shows the best picture and representation of this will be part of a con- test to a state will great opportunity for mountain-biking and using a Liv bike. On this trip, everything will be sponsored by Liv. In addition, Liv will sponsor a Liv festival, where the purpose of the festival is to donate to breast cancer, as we are dealing with women. -

Bike Manufacturers

Bike Manufacturers Bicycle Manufacturers This page is provided so that you can find your bicycle based on the manufacturer. See a manufacturer not listed? Add it here! 0-9 3T Cycling A A-bike Abici Adler AIST ALAN Albert Eisentraut Alcyon Alldays & Onions American Bicycle Company American Eagle American Machine and Foundry American Star Bicycle Aprilia Argon 18 Ariel Atala Author Avanti B B'Twin Baltik vairas Bacchetta Barnes Cycle Company Basso Bikes Batavus Battaglin Berlin & Racycle Manufacturing Company BH Benno Bikes Bianchi Bickerton Bike Friday Bilenky Biomega Birdy BMC BMW Boardman Bikes Bohemian Bicycles Bootie Bottecchia Bradbury Brasil & Movimento Brennabor Bridgestone British Eagle Brodie Bicycles Brompton Bicycle Brooklyn Bicycle Co. Browning Arms Company Brunswick BSA Burley Design C Calcott Brothers Calfee Design Caloi Campion Cycle Company Cannondale Canyon bicycles Catrike CCM Centurion Cervélo Chappelli Cycles Chater-Lea Chicago Bicycle Company CHUMBA Cilo Cinelli Ciombola Clark-Kent Claud Butler Clément Co-Motion Cycles Coker Colnago Columbia Bicycles Corima Cortina Cycles Coventry-Eagle Cruzbike Cube Bikes Currys Cycle Force Group Cycles Devinci Cycleuropa Group Cyclops Cyfac D Dahon Dario Pegoretti Dawes Cycles Defiance Cycle Company Demorest Den Beste Sykkel (better known as DBS) Derby Cycle De Rosa Cycles Devinci Di Blasi Industriale Diamant Diamant Diamondback Bicycles Dolan Bikes Dorel Industries Dunelt Dynacraft E Esmaltina Eagle Bicycle Manufacturing Company Edinburgh Bicycle Cooperative Eddy Merckx Cycles Electra