The Effect of School Closure On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCI Approved List

LIST OF APPROVED MODELS OF FRAMES AND FORKS Version on 11.08.2016 The Approval Procedure of bicycle frames and came into force on 1 January 2011 in accordance with Article 1.3.001bis of the UCI Regulations. From this date, all new models of frames and forks used by licence holders in road (RD), time trial (TT), track (TR) and cyclo-cross (CX) events must be approved on the basis of the Approval Protocol for Frames and Forks available from the UCI website. Approval by the UCI certifies that the new equipment meets the shape requirements set out in the UCI regulations. However, this approval does not certify in any case the safety of the equipment which must meet the applicable official quality and safety standards, in accordance with Article 1.3.002 of the UCI regulations. The models which are subject to the approval procedure are: all new models of frames and forks used by licence holders in road, track or cyclo-cross events, all models of frames and forks under development on 1 January 2011 which had not yet reached the production stage (the date of the order form of the moulds is evidence), any changes made to the geometry of existing models after 1 January 2011. Models on the market, at the production stage or already manufactured on 1 January 2011 are not required to be approved during the transition stage. However, the non-approved models have to comply in any case with the UCI technical regulations (Articles 1.3.001 to 1.3.025) and are subjects to the commissaires decision during events. -

Solar and Human Power Operated Vehicle with Drive Train

ISSN(Online) : 2319-8753 ISSN (Print) : 2347-6710 International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology (An ISO 3297: 2007 Certified Organization) Website: www.ijirset.com Vol. 6, Issue 4, April 2017 Solar and Human Power Operated Vehicle with Drive Train Prof. Krishna Shrivastava1, NileshWani2, Shoyab Shah3 Associate Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Dept. SSBT’s COET, Jalgaon Maharashtra, India1 U.G. Student, , Department of Mechanical Engineering, SSBT’s COET, Jalgaon Maharashtra, India 2 U.G. Student, , Department of Mechanical Engineering, SSBT’s COET, Jalgaon Maharashtra, India 3 ABSTRACT: It is highly essential to produce an alternative vehicle for students travelling for short distance in city. Bicycle is used for transportation, but possessing discomfort with physical exertion required pedaling over roads and uneven terrains. The traditional tricycles are arranged with extremely high gear ratio. A power assist will improve Bicycle comfort and easy for driver to drive it with comfort. This project deals with design and fabrication of bicycle powered by human and solar energy with drive trains having low gear ratio. This results to minimize the problems and constraints over the traditional bicycle and can be frequently used by school/college students. KEYWORDS: Solar Energy, Bicycle, Tricycle, Drive Train I.INTRODUCTION Solar energy is use in various industries. Solar energy having wide range of application. It is unlimited source of energy that is why we have to utilize solar energy. Solar tricycle takes power from solar energy and paddle mechanism both. It may be called as hybrid tricycle. The main cause to develop this is to reduce the use of fossils fuels used by scooters in India. -

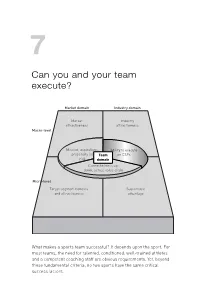

Can You and Your Team Execute?

Chapter7.qxd 28/4/06 2:10 pm Page 147 7 Can you and your team execute? Market domain Industry domain Market Industry attractiveness attractiveness Macro-level Mission, aspirations, AbilityAbility to to execute execute propensity for Team onon CSFs CSFs risk domain Connectedness up, down, across value chain Micro-level Target segment benefits Sustainable and attractiveness advantage What makes a sports team successful? It depends upon the sport. For most teams, the need for talented, conditioned, well-trained athletes and a competent coaching staff are obvious requirements. Yet, beyond these fundamental criteria, no two sports have the same critical success factors. Chapter7.qxd 28/4/06 2:10 pm Page 148 Take for example basketball, football and polo. Successful basketball teams must have players with the hand-eye coordination to shoot the ball accurately. Having tall players doesn’t hurt, either, of course. On the other hand, football (soccer) is played largely with the feet, so hand–eye coordination doesn’t matter very much. Agility and an ability to control the ball while keeping one’s head and eyes up are critical, however. A polo team’s success depends on both the athletes and the horses. As in basketball and football, the athletes need to have a good shot, but they must also be able to make this shot while riding a horse at high speed. In all three sports, endurance also matters – the fittest team often wins. In each of these sports, different factors are critical to success. Height and shooting ability make a big difference in basketball. Foot skills and the ability to maintain possession of the ball are important in football. -

Nathan Anthony Resch, Robert Higham, Ashley

COURT FILE NO.: 00-CV-189420 DATE: 20060413 SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE - ONTARIO RE: Nathan Anthony Resch, Robert Higham, Ashley Higham, Ashley Crayden, Shannon Crayden, minors under the age of 18 years by their Litigation Guardian, Annette Crayden, Joan Crayden, John Crayden, Annette Crayden and Mark Crayden, Plaintiffs A N D: 2006 CanLII 11930 (ON S.C.) Canadian Tire Corporation Limited, Mills-Roy Enterprises Limited, Gestion R.A.D. Inc., Procycle Group Inc. BEFORE: Justice Spies COUNSEL: L. Craig Brown & Darcy Merkur, for the Plaintiffs Mark Edwards & Aaron Murray, for the Defendants Canadian Tire Corporation Limited, Gestion R.A.D. and Procycle Group Inc. A. Peter Trebuss for the Defendant Mills-Roy Enterprises Limited. HEARD: By way of written submissions during the course of the trial ENDORSEMENT Overview [1] In the present action, the plaintiffs, Nathan Resch and his immediate family, claim damages from the defendants for negligence. The claim against Mills-Roy Enterprises Ltd. is also for breach of contract under the Sale of Goods Act,1 (the “Act”) and in particular reliance on the implied warranty of fitness under s. 15 of the Act in connection with a CCM Heat mountain bicycle purchased from Mills-Roy, a Canadian Tire dealer. Resch was seriously injured after an accident on the bicycle. The bicycle was manufactured by Procycle Group Inc. and sold to Canadian Tire Corporation Limited, which in turn sold the bicycle to Mills-Roy. There are cross- claims between the defendants Canadian Tire Corporation Limited, Gestion R.A.D. and Procycle Group Inc. (“Procycle defendants”) and Mills-Roy for contribution and indemnity pursuant to 1 R.S.O. -

1976-77-Annual-Report.Pdf

TheCanada Council Members Michelle Tisseyre Elizabeth Yeigh Gertrude Laing John James MacDonaId Audrey Thomas Mavor Moore (Chairman) (resigned March 21, (until September 1976) (Member of the Michel Bélanger 1977) Gilles Tremblay Council) (Vice-Chairman) Eric McLean Anna Wyman Robert Rivard Nini Baird Mavor Moore (until September 1976) (Member of the David Owen Carrigan Roland Parenteau Rudy Wiebe Council) (from May 26,1977) Paul B. Park John Wood Dorothy Corrigan John C. Parkin Advisory Academic Pane1 Guita Falardeau Christopher Pratt Milan V. Dimic Claude Lévesque John W. Grace Robert Rivard (Chairman) Robert Law McDougall Marjorie Johnston Thomas Symons Richard Salisbury Romain Paquette Douglas T. Kenny Norman Ward (Vice-Chairman) James Russell Eva Kushner Ronald J. Burke Laurent Santerre Investment Committee Jean Burnet Edward F. Sheffield Frank E. Case Allan Hockin William H. R. Charles Mary J. Wright (Chairman) Gertrude Laing J. C. Courtney Douglas T. Kenny Michel Bélanger Raymond Primeau Louise Dechêne (Member of the Gérard Dion Council) Advisory Arts Pane1 Harry C. Eastman Eva Kushner Robert Creech John Hirsch John E. Flint (Member of the (Chairman) (until September 1976) Jack Graham Council) Albert Millaire Gary Karr Renée Legris (Vice-Chairman) Jean-Pierre Lefebvre Executive Committee for the Bruno Bobak Jacqueline Lemieux- Canadian Commission for Unesco (until September 1976) Lope2 John Boyle Phyllis Mailing L. H. Cragg Napoléon LeBlanc Jacques Brault Ray Michal (Chairman) Paul B. Park Roch Carrier John Neville Vianney Décarie Lucien Perras Joe Fafard Michael Ondaatje (Vice-Chairman) John Roberts Bruce Ferguson P. K. Page Jacques Asselin Céline Saint-Pierre Suzanne Garceau Richard Rutherford Paul Bélanger Charles Lussier (until August 1976) Michael Snow Bert E. -

ROAD TEST: the Rivendell Atlantis Unparalleled Beauty, and As Rugged and Versatile As It Gets

CYCLE SENSE ROAD TEST: The Rivendell Atlantis Unparalleled beauty, and as rugged and versatile as it gets. by John Schubert In the last few years, a selection of rugged-and-reliable touring bikes has graced these pages. Many more such bikes are available but not (yet) reviewed here. Usually, small nuances separate these bikes from one another. In the case of today’s bike, the Rivendell Atlantis, that’s true of the function part. The Atlantis is a tough-as-nails go-anywhere bike which, by dint of its ability to mount very wide tires, joins the few bikes at the top of the list in versatility and ruggedness. In personality, though, the Atlantis stands apart in a most delight- ful way. It combines sensible, rugged current-production components with a lugged steel frame far prettier than any other you’ll find at twice the price. Every functional nuance of the frame has been well thought out, and three of the frame’s tubes were custom designed for the Atlantis. The ornate lugwork is highlighted by contrast- color paint panels, and if you buy the complete bike from Rivendell, you’ll get the similarly dressy Nitto handlebars and lugged steel handlebar stem. Rivendell likes to send these bikes out with brown cloth handlebar tape, secured at the center of the handlebars with twine wrap and coated with shel- ULERY KREG BY ALL PLHOTOS lac. I recommend this highly. The shel- lac tape looks great and feels great. Three of the frame tubes used in the Atlantis were custom designed for Rivendell. -

GEN Wickam's 10000 Man Light Infantry Division

O[ A• F COP• ci AD-A211 795 HUMAN POWERED VEHICLES IN SUPPORT OF LIGHT INFANTRY OPERATIONS A thesis presented to the Faculty of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MILITARY ART AND SCIENCE by STEPHEN T. TATE, MAJ, USA B.S., Middle Tennessee State University, 1975 AftDTIC LECTE zPn AUG 3 0 1989 D. 3 Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 1989 APPROVED FOP IUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED 89 8 29 022 UNCLASSIFIED JECURITY CLASSIFICATINo THfF AVW~ =IOfNo. 0704-0 188 I~~~~01REOT, pp. 0ro4-,ved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE .... I'a1.6•EPOfT SlTY, Clb RESTRICTIVE MARKINGS nC i. eE~,~~dCLASSIFCATION 3 PiýTRIBUTIgNIIAVAILAt.TY OF RSPORT 2e. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION AUTHORITY Approved 1or public release; 2b. DECLASSIFICATION/DOWNGRADING SCHE-DULE distributir., is unlimited. 4. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) 5. MONITORING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) 6a. NAME OF PERFORMING ORGANIZATION 6b. OFFICE SYMBOL 7a. NAME OF MONITORING ORGANIZATION U.S. Army Command and (If applicable) General Staff College ATZL-SWD-GD 6C. ADDRESS (Ciy,' State, and ZIP Code) 7b. ADDRESS (City, State, and ZIP Code) U.S. Army Command & General Staff College Fort Leavenworth, KS 66027-6900 Ba. NAME OF FUNDING/SPONSORING Bb. OFFICE SYMBOL 9. OROCUREMENT INSTRUMENT IDENTIFICATION NUMBER ORGANIZATION (If applicable) ac. ADDRESS(City, State, and ZIP Code) 10 SOURCE OF FUNDING NUMBERS PROGRAM PROJECT TASK WORK UNIT ELEMENT NO. NO. NO. ACCESSION NO. 1i. 1iT L-t include Securivy Cias.sificarion) Human Powered Vehicles in Support of Light Infantry Operations 12. PERSONAL AUTHOR(S) Major Stephen T. -

4-H Bicycling Project – Reference Book

4-H MOTTO Learn to do by doing. 4-H PLEDGE I pledge My HEAD to clearer thinking, My HEART to greater loyalty, My HANDS to larger service, My HEALTH to better living, For my club, my community and my country. 4-H GRACE (Tune of Auld Lang Syne) We thank thee, Lord, for blessings great On this, our own fair land. Teach us to serve thee joyfully, With head, heart, health and hand. This project was developed through funds provided by the Canadian Agricultural Adaptation Program (CAAP). No portion of this manual may be reproduced without written permission from the Saskatchewan 4-H Council, phone 306-933-7727, email: [email protected]. Developed in January 2013. Writer: Leanne Schinkel Table of Contents Introduction Objectives .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Getting the Most from this Project ....................................................................................................... 1 Achievement Requirements for this Project ..................................................................................... 2 Safety and Bicycling ................................................................................................................................. 2 Online Safety .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Resources for Learning ............................................................................................................................ -

Blackstone Bicycle Works

Blackstone Bicycle Works Refurbished Bicycle Buyers Guide Always wear a helmet and make sure it fits! • Blackstone Bicycle Works sells donated bicycles that we refurbish and sell to help support our youth program. There are different types of bicycles that are good for different styles of riding. • What type of riding would you like to do on your new refurbished bicycle? Choosing Your Bicycle Types of Bicycles at Blackstone Bicycle Works The Cruiser Cruisers have a laid-back upright position for a more comfortable ride. Usually a single speed and sometimes has a coaster brake. Some cruisers also have internally geared hubs that can range from 3-speed and up. With smooth and some-times wider tires this bicycle is great for commuting and utility transport of groceries and other supplies. Add a front basket and rear rack easily to let the bike do the work of carrying things. Most cruisers will accept fenders to help protect you and the bicycle from the rain and snow. The Hybrid Bicycle A hybrid bicycle is mix of a road and mountain bicycle. These bicycles offer a range in gearing and accept wider tires than road bikes do. Some hybrids have a suspension fork while others are rigid. Hybrid bicycles are great for commuting in the winter months because the wider tires offer more stability. You can ride off-road, but it is not recommended for mountain bike trails or single-track riding. Great for gravel and a good all-around versatile bicycle. Great for utility, commuting and for leisure rides to and from the lake front. -

Circle of Two What Poverty Does to Most People

REVIEWS was closer to Steinbeck than to Dostoev we associate with Wamer Bros, shop Claude Foumier's ski- there's something broad-shouldered girls of the same period. And yet Dey Jules Dassin's and strongbacked about her work, and glun, with her wade-set eyes and blunt Bonheur d'occasion gets that on film features, reveals in the most unobtrusive Bonheur along with her deep understanding of ways just how vulnerable and worn- Circle of Two what poverty does to most people. In down Florentine is as she schemes her her books it doesn't usually make them way upward into respectability by con d'occasion heroic or mad or even criminal, it just ning a man she doesn't love into marry reduces them to so much less than they ing her. For an experienced film actress, might have been under different and such a carefully shaded (and frequently It's the easiest thing in the world to slightly better circumstances, forcing funny) Florentine would be a major when Circle of Two was finally shown, dismiss Bonheur d'occasion (The Tin them to compromise in ways most of us accomplishment; as Deyglun's first after several false starts, on CBCs winter Flute) as just another six-handkerchief never have to. screen role, Florentine is nothing less series of Canadian films, it brought to an weeper. God knows misery and tears Veteran Quebec director Claude Four than a triumph. end the rather sorry history of the Film Consortium of Canada. The hopes abound in this two-hour French-lan nier gets the right look for the book - St Marilyn Lightstone, who plays Floren engendered six years ago after the guage adaptation of the late Gabrielle Henri's dirty snow and peeling paint tine's mother with decidedly mixed and unexpected success of Outrageous, that Roy's novel of the same title in which and a sky choked with blue-black smoke bathetic results, has been cackling to Bill Marshall and Henk Van Der Kolk young Florentine Lacasse, daughter of from coal-buming furnaces and the the press about the movie's reception at would be the bright lights of the English- Montreal's working-class St. -

Bicycles Mcp-2776 a Global Strategic Business Report

BICYCLES MCP-2776 A GLOBAL STRATEGIC BUSINESS REPORT CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION, METHODOLOGY & Pacific Cycles Launches New Sting-Ray .............................II-16 PRODUCT DEFINITIONS Mongoose Launches Ritual ..................................................II-16 Multivac Unveils Battery-Powered Bicycle .........................II-17 TI Launches New Range of Mountain Terrain Bikes ...........II-17 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TI Inaugurates its First Cycleworld Outlet ...........................II-17 Shanghai Greenlight Electric Bicycle Launches 1. Introduction................................................................. II-1 Powerzinc Electric ............................................................II-17 Smith & Wesson Introduces Mountain Bikes in 2. Industry Overview ...................................................... II-2 Three Models....................................................................II-17 Historic Review......................................................................II-2 Diggler Unveils a Hybrid Machine.......................................II-17 Manufacturing Base Shifting to Southeast Asia .....................II-2 Avon Introduces New Range of Bicycle Models..................II-18 Manufacturing Trends............................................................II-3 Dorel Launches a New Line of Bicycle Ranges ...................II-18 Factors Affecting the Bicycle Market.....................................II-3 Ford Vietnam Launches Electric Bicycles............................II-18 Characteristics of the -

The Saxophone in China: Historical Performance and Development

THE SAXOPHONE IN CHINA: HISTORICAL PERFORMANCE AND DEVELOPMENT Jason Pockrus Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Eric M. Nestler, Major Professor Catherine Ragland, Committee Member John C. Scott, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Pockrus, Jason. The Saxophone in China: Historical Performance and Development. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 222 pp., 12 figures, 1 appendix, bibliography, 419 titles. The purpose of this document is to chronicle and describe the historical developments of saxophone performance in mainland China. Arguing against other published research, this document presents proof of the uninterrupted, large-scale use of the saxophone from its first introduction into Shanghai’s nineteenth century amateur musical societies, continuously through to present day. In order to better describe the performance scene for saxophonists in China, each chapter presents historical and political context. Also described in this document is the changing importance of the saxophone in China’s musical development and musical culture since its introduction in the nineteenth century. The nature of the saxophone as a symbol of modernity, western ideologies, political duality, progress, and freedom and the effects of those realities in the lives of musicians and audiences in China are briefly discussed in each chapter. These topics are included to contribute to a better, more thorough understanding of the performance history of saxophonists, both native and foreign, in China.