Preclinical Development of a Non-Immunosuppressive FTY720 Derivative OSU-2S for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia and Other B-Cell Malignancies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Sjogren Syndrome: Focus on Innate Immune Cells and Inflammation

Review Primary Sjogren Syndrome: Focus on Innate Immune Cells and Inflammation Chiara Rizzo 1, Giulia Grasso 1, Giulia Maria Destro Castaniti 1, Francesco Ciccia 2 and Giuliana Guggino 1,* 1 Department of Health Promotion, Mother and Child Care, Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties, Rheumatology Section, University of Palermo, Piazza delle Cliniche 2, 90110 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] (C.R.); [email protected] (G.G.); [email protected] (G.M.D.C.) 2 Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Via L. De Crecchio 7, 80138 Naples, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-091-6552260 Received: 30 April 2020; Accepted: 29 May 2020; Published: 3 June 2020 Abstract: Primary Sjogren Syndrome (pSS) is a complex, multifactorial rheumatic disease that mainly targets salivary and lacrimal glands, inducing epithelitis. The cause behind the autoimmunity outbreak in pSS is still elusive; however, it seems related to an aberrant reaction to exogenous triggers such as viruses, combined with individual genetic pre-disposition. For a long time, autoantibodies were considered as the hallmarks of this disease; however, more recently the complex interplay between innate and adaptive immunity as well as the consequent inflammatory process have emerged as the main mechanisms of pSS pathogenesis. The present review will focus on innate cells and on the principal mechanisms of inflammation connected. In the first part, an overview of innate cells involved in pSS pathogenesis is provided, stressing in particular the role of Innate Lymphoid Cells (ILCs). Subsequently we have highlighted the main inflammatory pathways, including intra- and extra-cellular players. -

Recombinant Human NCR3/Nkp300 Protein

Leader in Biomolecular Solutions for Life Science Recombinant Human NCR3/NKp300 Protein Catalog No.: RP00179 Recombinant Sequence Information Background Species Gene ID Swiss Prot Natural Cytotoxicity Triggering Receptor 3, NCR3, also known as NKp30, or CD337, Human 259197 O14931 is a natural cytotoxicity receptor. NKp30 is expressed on both resting and activated NK cells of the CD56dim, CD16+ subset that account for more that 85% of NK cells Tags found in peripheral blood and spleen. NKp30 is absent from the CD56bright, CD16- C-Fc & 6×His subset that constitutes the majority of NK cells in lymph node and tonsil, however, its expression is up-regulated in these cells upon IL-2 activation .NKp30 is a Synonyms member of the immunoglobulin superfamily and one of three existing natural 1C7;CD337;DAAP-90L16.3;LY117;MALS cytotoxicity-triggering receptors. NKp30 is a glycosylated protein and is thought to ;NCR3;NKp30 be selectively expressed in resting and activated natural killer cells. NKp30 is a stimulatory receptor on human NK cells implicated in tumor immunity, and is capable of promoting or terminating dendritic cell maturation. NCR3 may play a role in inflammatory and infectious diseases. Product Information Source Purification Basic Information HEK293 cells > 95% by SDS- PAGE. Description Recombinant Human NCR3/NKp300 Protein is produced by HEK293 cells Endotoxin expression system. The target protein is expressed with sequence (Leu19-Thr138) < 0.1 EU/μg of the protein by LAL of human NCR3/NKp300 (Accession #NP_001138938.1) fused with an Fc, 6×His tag method. at the C-terminus. Formulation Bio-Activity Lyophilized from a 0.22 μm filtered Measured by its binding ability in a functional ELISA. -

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

Meconium Ileus Caused by Mutations in GUCY2C, Encoding the CFTR-Activating Guanylate Cyclase 2C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector REPORT Meconium Ileus Caused by Mutations in GUCY2C, Encoding the CFTR-Activating Guanylate Cyclase 2C Hila Romi,1,6 Idan Cohen,1,6 Daniella Landau,2 Suliman Alkrinawi,2 Baruch Yerushalmi,2 Reli Hershkovitz,3 Nitza Newman-Heiman,2 Garry R. Cutting,4 Rivka Ofir,1 Sara Sivan,1 and Ohad S. Birk1,5,* Meconium ileus, intestinal obstruction in the newborn, is caused in most cases by CFTR mutations modulated by yet-unidentified modi- fier genes. We now show that in two unrelated consanguineous Bedouin kindreds, an autosomal-recessive phenotype of meconium ileus that is not associated with cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by different homozygous mutations in GUCY2C, leading to a dramatic reduction or fully abrogating the enzymatic activity of the encoded guanlyl cyclase 2C. GUCY2C is a transmembrane receptor whose extracellular domain is activated by either the endogenous ligands, guanylin and related peptide uroguanylin, or by an external ligand, Escherichia coli (E. coli) heat-stable enterotoxin STa. GUCY2C is expressed in the human intestine, and the encoded protein activates the CFTR protein through local generation of cGMP. Thus, GUCY2C is a likely candidate modifier of the meconium ileus phenotype in CF. Because GUCY2C heterozygous and homozygous mutant mice are resistant to E. coli STa enterotoxin-induced diarrhea, it is plausible that GUCY2C mutations in the desert-dwelling Bedouin kindred are of selective advantage. Meconium ileus (MI), intestinal obstruction by inspissated homozygosity on chromosome 12p13 (spanning 9.5 Mb meconium in the distal ileum and cecum, develops in between markers D12S366 and D12S310) that was utero and presents shortly after birth as failure to pass common to all affected individuals. -

Associated B Cell Lymphoma and Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

Contribution of tumour cell signalling and the microenvironment to the pathogenesis of EBV- associated B cell lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma BY MAHA IBRAHIM A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Institute of Cancer and Genomic Sciences College of Medical and Dental Sciences University of Birmingham May 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract In this thesis I have explored different components of the pathogenesis of several related EBV associated cancers. In the first part of the thesis I focus on the microenvironment of two of these cancers, nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) and diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Our group has developed a therapeutic vaccine against EBV which has already been shown to be safe in patients with NPC. Therefore, in the first results chapter (chapter 3), I present a description of the phenotyping of expression of the immune microenvironment including immune checkpoint (ICP) genes and MHC class I and class II genes in NPC tissues. I showed for the first time in NPC tissue samples, two types of PD-L1 expressing tumours: diffuse and marginal. -

Cancer Drug Pharmacology Table

CANCER DRUG PHARMACOLOGY TABLE Cytotoxic Chemotherapy Drugs are classified according to the BC Cancer Drug Manual Monographs, unless otherwise specified (see asterisks). Subclassifications are in brackets where applicable. Alkylating Agents have reactive groups (usually alkyl) that attach to Antimetabolites are structural analogues of naturally occurring molecules DNA or RNA, leading to interruption in synthesis of DNA, RNA, or required for DNA and RNA synthesis. When substituted for the natural body proteins. substances, they disrupt DNA and RNA synthesis. bendamustine (nitrogen mustard) azacitidine (pyrimidine analogue) busulfan (alkyl sulfonate) capecitabine (pyrimidine analogue) carboplatin (platinum) cladribine (adenosine analogue) carmustine (nitrosurea) cytarabine (pyrimidine analogue) chlorambucil (nitrogen mustard) fludarabine (purine analogue) cisplatin (platinum) fluorouracil (pyrimidine analogue) cyclophosphamide (nitrogen mustard) gemcitabine (pyrimidine analogue) dacarbazine (triazine) mercaptopurine (purine analogue) estramustine (nitrogen mustard with 17-beta-estradiol) methotrexate (folate analogue) hydroxyurea pralatrexate (folate analogue) ifosfamide (nitrogen mustard) pemetrexed (folate analogue) lomustine (nitrosurea) pentostatin (purine analogue) mechlorethamine (nitrogen mustard) raltitrexed (folate analogue) melphalan (nitrogen mustard) thioguanine (purine analogue) oxaliplatin (platinum) trifluridine-tipiracil (pyrimidine analogue/thymidine phosphorylase procarbazine (triazine) inhibitor) -

Supp Table 1.Pdf

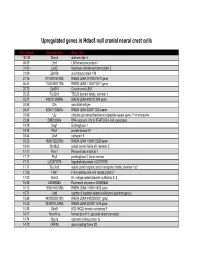

Upregulated genes in Hdac8 null cranial neural crest cells fold change Gene Symbol Gene Title 134.39 Stmn4 stathmin-like 4 46.05 Lhx1 LIM homeobox protein 1 31.45 Lect2 leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 31.09 Zfp108 zinc finger protein 108 27.74 0710007G10Rik RIKEN cDNA 0710007G10 gene 26.31 1700019O17Rik RIKEN cDNA 1700019O17 gene 25.72 Cyb561 Cytochrome b-561 25.35 Tsc22d1 TSC22 domain family, member 1 25.27 4921513I08Rik RIKEN cDNA 4921513I08 gene 24.58 Ofa oncofetal antigen 24.47 B230112I24Rik RIKEN cDNA B230112I24 gene 23.86 Uty ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat gene, Y chromosome 22.84 D8Ertd268e DNA segment, Chr 8, ERATO Doi 268, expressed 19.78 Dag1 Dystroglycan 1 19.74 Pkn1 protein kinase N1 18.64 Cts8 cathepsin 8 18.23 1500012D20Rik RIKEN cDNA 1500012D20 gene 18.09 Slc43a2 solute carrier family 43, member 2 17.17 Pcm1 Pericentriolar material 1 17.17 Prg2 proteoglycan 2, bone marrow 17.11 LOC671579 hypothetical protein LOC671579 17.11 Slco1a5 solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1a5 17.02 Fbxl7 F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 7 17.02 Kcns2 K+ voltage-gated channel, subfamily S, 2 16.93 AW493845 Expressed sequence AW493845 16.12 1600014K23Rik RIKEN cDNA 1600014K23 gene 15.71 Cst8 cystatin 8 (cystatin-related epididymal spermatogenic) 15.68 4922502D21Rik RIKEN cDNA 4922502D21 gene 15.32 2810011L19Rik RIKEN cDNA 2810011L19 gene 15.08 Btbd9 BTB (POZ) domain containing 9 14.77 Hoxa11os homeo box A11, opposite strand transcript 14.74 Obp1a odorant binding protein Ia 14.72 ORF28 open reading -

The Biochemistry of Gout: a USMLE Step 1 Study Aid

The Biochemistry of Gout: A USMLE Step 1 Study Aid BMS 6204 May 26, 2005 Compiled by: Todd Kerensky Elizabeth Ballard Brendan Prendergast Eric Ritchie 1 Introduction Gout is a systemic disease caused by excess uric acid as the result of deficient purine metabolism. Clinically, gout is marked by peripheral arthritis and painful inflammation in joints resulting from deposition of uric acid in joint synovia as monosodium urate crystals. Although gout is the most common crystal-induced arthritis, a condition known as pseudogout can commonly be mistaken for gout in the clinic. Pseudogout results from deposition of calcium pyrophosphatase (CPP) crystals in synovial spaces, but causes nearly identical clinical presentation. Clinical findings Crystal-induced arthritis such as gout and pseudogout differ from other types of arthritis in their clinical presentations. The primary feature differentiating gout from other types of arthritis is the spontaneity and abruptness of onset of inflammation. Additionally, the inflammation from gout and pseudogout are commonly found in a single joint. Gout and pseudogout typically present with Podagra, a painful inflammation of the metatarsal- phalangeal joint of the great toe. However, gout can also present with spontaneous edema and painful inflammation of any other joint, but most commonly the ankle, wrist, or knee. As an exception, a spontaneous painful inflammation in the glenohumeral joint is usually the result of pseudogout. It is important to recognize the clinical differences between gout, pseudogout and other types of arthritis because the treatments differ markedly (Kaplan 2005). Pathophysiology and Treatment of Gout Although gout affects peripheral joints in clinical presentation, it is important to recognize that it is a systemic disorder caused by either overproduction or underexcretion of uric acid. -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

Analysis of Tautomeric Equilibrium of the Analogue D(Dinitro-Tc(O))TP During Incorporation by the Klenow Fragment of DNA Polymerase I

Analysis of Tautomeric Equilibrium of the Analogue d(dinitro-tC(O))TP During Incorporation by the Klenow Fragment of DNA Polymerase I Arielle Baker Monday, April 7th, 2014: 4:00pm Thesis Advisor Robert Kuchta, Ph.D. | Dept. of Chemistry and Biochemistry Committee Members Robert Knight, Ph.D. | Dept. of Chemistry and Biochemistry Jennifer Martin, Ph.D. | Dept. of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors in the Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Acknowledgements My most heartfelt thanks goes to my advisor, mentor and friend Dr. Rob Kuchta, for his unending patience and willingness to share his knowledge with me, as well as his continued support for my pursuit of science. I would like to thank my friends in the Kuchta lab, and to some colleagues in particular. Thank you to Dr. Andrew Olsen and Dr. Gudrun Stengel for being the very first overseers of my work, and for not scaring me off. Thanks to Dr. Ashwani Vashishtha, Dr. Joshua Gosling, Sarah Dickerson, Clarinda Hougen and Taylor Minckley for the many laughs we’ve shared benchside, and for answering even the most insignificant of questions. Thank you to my committee members, Dr. Jennifer Martin and Dr. Rob Knight, for their assistance in navigating my thesis work. My work would not have been possible without generous funding from the National Institutes of Health. Thank you to my dear friend Makenna Morck for always being available to discuss biochemistry with me in the wee hours of the morning. -

Supplementary Table S5. Differentially Expressed Gene Lists of PD-1High CD39+ CD8 Tils According to 4-1BB Expression Compared to PD-1+ CD39- CD8 Tils

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) J Immunother Cancer Supplementary Table S5. Differentially expressed gene lists of PD-1high CD39+ CD8 TILs according to 4-1BB expression compared to PD-1+ CD39- CD8 TILs Up- or down- regulated genes in Up- or down- regulated genes Up- or down- regulated genes only PD-1high CD39+ CD8 TILs only in 4-1BBneg PD-1high CD39+ in 4-1BBpos PD-1high CD39+ CD8 compared to PD-1+ CD39- CD8 CD8 TILs compared to PD-1+ TILs compared to PD-1+ CD39- TILs CD39- CD8 TILs CD8 TILs IL7R KLRG1 TNFSF4 ENTPD1 DHRS3 LEF1 ITGA5 MKI67 PZP KLF3 RYR2 SIK1B ANK3 LYST PPP1R3B ETV1 ADAM28 H2AC13 CCR7 GFOD1 RASGRP2 ITGAX MAST4 RAD51AP1 MYO1E CLCF1 NEBL S1PR5 VCL MPP7 MS4A6A PHLDB1 GFPT2 TNF RPL3 SPRY4 VCAM1 B4GALT5 TIPARP TNS3 PDCD1 POLQ AKAP5 IL6ST LY9 PLXND1 PLEKHA1 NEU1 DGKH SPRY2 PLEKHG3 IKZF4 MTX3 PARK7 ATP8B4 SYT11 PTGER4 SORL1 RAB11FIP5 BRCA1 MAP4K3 NCR1 CCR4 S1PR1 PDE8A IFIT2 EPHA4 ARHGEF12 PAICS PELI2 LAT2 GPRASP1 TTN RPLP0 IL4I1 AUTS2 RPS3 CDCA3 NHS LONRF2 CDC42EP3 SLCO3A1 RRM2 ADAMTSL4 INPP5F ARHGAP31 ESCO2 ADRB2 CSF1 WDHD1 GOLIM4 CDK5RAP1 CD69 GLUL HJURP SHC4 GNLY TTC9 HELLS DPP4 IL23A PITPNC1 TOX ARHGEF9 EXO1 SLC4A4 CKAP4 CARMIL3 NHSL2 DZIP3 GINS1 FUT8 UBASH3B CDCA5 PDE7B SOGA1 CDC45 NR3C2 TRIB1 KIF14 TRAF5 LIMS1 PPP1R2C TNFRSF9 KLRC2 POLA1 CD80 ATP10D CDCA8 SETD7 IER2 PATL2 CCDC141 CD84 HSPA6 CYB561 MPHOSPH9 CLSPN KLRC1 PTMS SCML4 ZBTB10 CCL3 CA5B PIP5K1B WNT9A CCNH GEM IL18RAP GGH SARDH B3GNT7 C13orf46 SBF2 IKZF3 ZMAT1 TCF7 NECTIN1 H3C7 FOS PAG1 HECA SLC4A10 SLC35G2 PER1 P2RY1 NFKBIA WDR76 PLAUR KDM1A H1-5 TSHZ2 FAM102B HMMR GPR132 CCRL2 PARP8 A2M ST8SIA1 NUF2 IL5RA RBPMS UBE2T USP53 EEF1A1 PLAC8 LGR6 TMEM123 NEK2 SNAP47 PTGIS SH2B3 P2RY8 S100PBP PLEKHA7 CLNK CRIM1 MGAT5 YBX3 TP53INP1 DTL CFH FEZ1 MYB FRMD4B TSPAN5 STIL ITGA2 GOLGA6L10 MYBL2 AHI1 CAND2 GZMB RBPJ PELI1 HSPA1B KCNK5 GOLGA6L9 TICRR TPRG1 UBE2C AURKA Leem G, et al. -

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Stratify Clinical Response to csDMARD-Therapy and Predict Radiographic Progression Frances Humby1,* Myles Lewis1,* Nandhini Ramamoorthi2, Jason Hackney3, Michael Barnes1, Michele Bombardieri1, Francesca Setiadi2, Stephen Kelly1, Fabiola Bene1, Maria di Cicco1, Sudeh Riahi1, Vidalba Rocher-Ros1, Nora Ng1, Ilias Lazorou1, Rebecca E. Hands1, Desiree van der Heijde4, Robert Landewé5, Annette van der Helm-van Mil4, Alberto Cauli6, Iain B. McInnes7, Christopher D. Buckley8, Ernest Choy9, Peter Taylor10, Michael J. Townsend2 & Costantino Pitzalis1 1Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, UK. Departments of 2Biomarker Discovery OMNI, 3Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, California 94080 USA 4Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands 5Department of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Amsterdam Rheumatology & Immunology Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 6Rheumatology Unit, Department of Medical Sciences, Policlinico of the University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy 7Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8TA, UK 8Rheumatology Research Group, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing (IIA), University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2WB, UK 9Institute of